pragmatism

∞

The Sentiment That Invites Us To Pray - Peirce on Prayer and Inquiry

"One of Peirce’s ongoing aims was

to reconcile religious life with the practice and spirit of science.

Given the great differences between religion and science—in both

practical and theoretical terms—this may have seemed like a fool’s

errand in his time, and even more so in our time. The spirit of science

is one of progress and fallibility, an open community whose only heresy

is an unwillingness to seek the truth, while the spirit of religion

includes a tendency towards conservative closure of inquiry and of

membership. While Peirce acknowledged these distinctions, he

nevertheless maintained that religion was not necessarily

opposed to science. Certain aspects of religious practice —and

especially the act of prayer—exemplify elements of inquiry. Rather than

causing thought to contract and community to become less important, as

is often supposed, practice in prayer may be a creative act, like

poetry, that can in fact lead to greater understanding of the world and

of one’s place in it. At its best, prayer arises from an instinct or

from a sentiment, and it affords comfort, strength, and—perhaps most

importantly—insight into the nature of the world...."

Read the rest here, in the latest volume of the Journal Of Scriptural Reasoning.

Read the rest here, in the latest volume of the Journal Of Scriptural Reasoning.

∞

Socratic Pragmatism: On Our Attitude Towards Inquiry

"I do not insist that my argument is right in all other respects, but I would contend at all costs in both word and deed as far as I could that we will be better men, braver and less idle, if we believe that one must search for the things one does not know, rather than if we believe that it is not possible to find out what we do not know and that we must not look for it."

Socrates, in Plato’s Meno, 86b-. G.M.A. Grube, trans.

∞

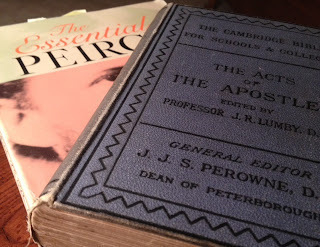

Pragmatist Scripture: Peirce and The Book of Acts

A few months ago a friend who is interested in both scripture and philosophy asked me which scripture mattered most to Charles Peirce. One obvious answer would be the writings of John, the gospeller of agape love, since agape plays such a great role in Peirce's philosophy.

The Book of Acts has recently come to mind as another strong candidate, for several reasons. I plan to write about all this in more detail soon, but I'll use this space to jot down my thinking quickly, in order to make it available to anyone who might be interested, in the Peircean spirit of shared inquiry.

The Greek title of the Book of Acts is Praxeis Apostolon, or the Deeds of the Apostles. We guess that the author of the text was the same as the author of the Gospel attributed to Luke. The title might well have been added after the book was in circulation for a while, but that's probably inconsequential. It occurred to me recently that this text begins with reminding us that the author wrote a previous book about "the things Jesus began to do and to teach," and then it narrates, without further introduction, the things that the first Christians did after Jesus' death and resurrection.

In other words, it is a book of acts, of deeds. It is a book of narratives about what people did.

Which is to say that it is not primarily a book of prayers, or of songs, or of doctrines. It tells a story, without much attempt to interpret that story. And it is the story of a community learning to work together, and learning how it must adjust its doctrines in light of the community's expansion across and into cultures, and in light of the surprising things they find the new community is empowered to accomplish.

This is appealing to Pragmatists like Peirce, who are more concerned with the way decisions lead to actions than with fixing metaphysical doctrines and whose notions of truth, ethics, and metaphysics are more experimental and transactional than systematic and permanent. Pragmatists are given to the idea that it is good for communities to work with tentative, revisable and fallible tenets, ever striving to improve their practices as the community grows.

*****

Peirce is not exactly easy to read, which helps to explain why most of what he wrote remains unpublished even a century after his death. Nevertheless, the patient reader of Peirce is often rewarded by a writer who took words very seriously.

Some of the words he used to great effect in his lectures and essays are derived from the Book of Acts. Among these phrases are a phrase he uses in his 1907 essay "A Neglected Argument For The Reality Of God," and one that comes at the end of his Cambridge Conference Lectures of 1898. The phrases are "scientific singleness of heart," and "things live and move and have their being in a logic of events." See Acts 2.46 and 17.28 for the sources of these two phrases. (The first one might also have come to Peirce through the Anglican Book of Common Prayer, as I have argued elsewhere.)

Two such phrases are not enough to make the case that Peirce was dependent on the Book of Acts, but thankfully that's not the case I'm trying to make. Peirce was well read and he cited other portions of scripture and, of course, many other books, after all. I only want to suggest that Peirce might have found the Book of Acts to be a scripture that resonates with his Pragmatism.

*****

That being said, I wish to point to one figure in the middle of the Book of Acts who might be taken to be a kind of Pragmatist saint: Epimenides.

I won't belabor that point here, as I have already written about it elsewhere. I'll only add that Epimenides appears to be the unnamed source that St Paul appeals to and cites in Acts 17.28.

The Book of Acts has recently come to mind as another strong candidate, for several reasons. I plan to write about all this in more detail soon, but I'll use this space to jot down my thinking quickly, in order to make it available to anyone who might be interested, in the Peircean spirit of shared inquiry.

The Greek title of the Book of Acts is Praxeis Apostolon, or the Deeds of the Apostles. We guess that the author of the text was the same as the author of the Gospel attributed to Luke. The title might well have been added after the book was in circulation for a while, but that's probably inconsequential. It occurred to me recently that this text begins with reminding us that the author wrote a previous book about "the things Jesus began to do and to teach," and then it narrates, without further introduction, the things that the first Christians did after Jesus' death and resurrection.

In other words, it is a book of acts, of deeds. It is a book of narratives about what people did.

Which is to say that it is not primarily a book of prayers, or of songs, or of doctrines. It tells a story, without much attempt to interpret that story. And it is the story of a community learning to work together, and learning how it must adjust its doctrines in light of the community's expansion across and into cultures, and in light of the surprising things they find the new community is empowered to accomplish.

This is appealing to Pragmatists like Peirce, who are more concerned with the way decisions lead to actions than with fixing metaphysical doctrines and whose notions of truth, ethics, and metaphysics are more experimental and transactional than systematic and permanent. Pragmatists are given to the idea that it is good for communities to work with tentative, revisable and fallible tenets, ever striving to improve their practices as the community grows.

*****

Peirce is not exactly easy to read, which helps to explain why most of what he wrote remains unpublished even a century after his death. Nevertheless, the patient reader of Peirce is often rewarded by a writer who took words very seriously.

Some of the words he used to great effect in his lectures and essays are derived from the Book of Acts. Among these phrases are a phrase he uses in his 1907 essay "A Neglected Argument For The Reality Of God," and one that comes at the end of his Cambridge Conference Lectures of 1898. The phrases are "scientific singleness of heart," and "things live and move and have their being in a logic of events." See Acts 2.46 and 17.28 for the sources of these two phrases. (The first one might also have come to Peirce through the Anglican Book of Common Prayer, as I have argued elsewhere.)

Two such phrases are not enough to make the case that Peirce was dependent on the Book of Acts, but thankfully that's not the case I'm trying to make. Peirce was well read and he cited other portions of scripture and, of course, many other books, after all. I only want to suggest that Peirce might have found the Book of Acts to be a scripture that resonates with his Pragmatism.

*****

That being said, I wish to point to one figure in the middle of the Book of Acts who might be taken to be a kind of Pragmatist saint: Epimenides.

I won't belabor that point here, as I have already written about it elsewhere. I'll only add that Epimenides appears to be the unnamed source that St Paul appeals to and cites in Acts 17.28.

∞

The Virtue of Virtue

Virtue ethics is problematic. It certainly is helpful at times, but it is not helpful when

it names virtues that others cannot relate to; or when we use it to describe

virtues that only certain classes of people can ever attain; or when virtues

entail a metaphysics to which others are unwilling to commit. The very word “virtue” raises a

red flag for some people because it is a gendered word, rooted in the Latin vir, meaning an adult male. I often wish we had a better

translation of the word Aristotle first used, arête, which means something like “excellence.”

At any rate, virtue ethics may have great value if we allow

Aristotle’s description of arête to

be a moving target, and if we appeal to it as an approach to governing our own

conduct rather than as a way to make rules for others. (Isn’t it the case that so often we

write rules for others rather than for ourselves? That should tell us something.)

Aristotle tells us that virtue is the mean between extremes,

as the man of practical wisdom would determine it. But which of us is the man of practical wisdom? No one of us has that down. So no one of us may be expected to

understand virtue exactly. This

would appear to be an argument for a collective decision, and to some degree it

is. Our public deliberations about

ethics, about methods of research, about law, about public conduct – all of

these are, in a way, attempts by groups of people to figure out what a truly

wise and prudent person would do.

So to some degree, communities and their traditions are

embodiments of decisions about virtue.

We must remember, however, that we’re always on the move, ever seeking,

never fully finding.

I am reminded of Kierkegaard’s citation of Lessing in

Kierkegaard’s Concluding Unscientific Postscript:

We live lives of unknowing, ever striving for what we might know. "Now we see as in a glass, darkly; now we see in part." And that's not so bad, is it? Peirce might call the belief that we don't know fully a regulative ideal; or I suppose, in Rorty’s terms, we might call it a pragmatic hope. If we take ourselves not to have arrived at perfect justice yet, that belief will drive us to keep seeking to improve our justice.“If God held all truth enclosed in his right hand, and in his left hand the one and only ever-striving drive for truth, even with the corollary of erring forever and ever, and if he were to say to me:--Choose! I would humbly fall down to him at his left hand and say: Father, give! Pure truth is indeed only for you alone!”*

You’ve read this far, so you’re probably ready for me to

make my point. Here it is: as we

talk about policies and politics, rules and laws—in short, when we are deeply

concerned with governing others—let us not neglect governing ourselves, by reflecting on, and trying to enact, virtue in our decisions. Life is uncertain. We do not know what will come next,

what we will be given, what will be taken away. But no one can take away the small decisions we make, the

small decisions that, one by one, make us.

******

*Soren Kierkegaard, Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992, Vol I) 106. The quotation is a citation from Lessing by Kierkegaard.

******

*Soren Kierkegaard, Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992, Vol I) 106. The quotation is a citation from Lessing by Kierkegaard.

∞

* ("Dmesis" is a Greek word that means "taming," or "breaking.")

Charles Peirce on Criminal Justice

I have posted briefly about Peirce's interest in criminal justice before. I haven't time to comment on it extensively now, so for now I will post this link to his piece entitled "Dmesis"* and these brief comments:

More than once commentators on Peirce's Pragmatism have argued that he does not pay attention to politics or to political, social, and ethical theory. This piece is not alone in refuting that thesis. It would be more accurate to say that for Peirce, it is impossible to treat social and ethical issues apart from the rest of his philosophy. Peirce was a synechist, which means he held that ideas are not independent atoms of thought but interdependent and interconnected with one another. Ideas affect one another.

More than once commentators on Peirce's Pragmatism have argued that he does not pay attention to politics or to political, social, and ethical theory. This piece is not alone in refuting that thesis. It would be more accurate to say that for Peirce, it is impossible to treat social and ethical issues apart from the rest of his philosophy. Peirce was a synechist, which means he held that ideas are not independent atoms of thought but interdependent and interconnected with one another. Ideas affect one another.

One great implication of this is that just as one idea affects another in our private thinking, so our personal beliefs affect other persons. Our ideas are not atoms, and neither are we. The foundation of ethics, and of all philosophy, is agape, or love. As Peirce wrote elsewhere,

“He who would not sacrifice his own soul to save the whole world, is illogical in all his inferences, collectively.”

Peirce makes the especially trenchant observation that if we really cared about criminals, then our criminal justice system would make positive habituation a guiding principle in the housing and treatment of prisoners. I'm willing to concede that Peirce may not be right in all he says here, but this point seems spot on: it is inconsistent to habituate people to prison life if our aim is to return them to society.

Peirce's conclusion in the third paragraph also seems right: the fact is, we imprison people "because we detest them."

* ("Dmesis" is a Greek word that means "taming," or "breaking.")