Prayer

- Forgive Onesimus, the indentured servant who ran away, breaking his contract with Philemon;

- Forgive Onesimus for stealing from Philemon as he fled;

- Welcome Onesimus back, not as a slave but as a family member.

∞

The Sentiment That Invites Us To Pray - Peirce on Prayer and Inquiry

"One of Peirce’s ongoing aims was

to reconcile religious life with the practice and spirit of science.

Given the great differences between religion and science—in both

practical and theoretical terms—this may have seemed like a fool’s

errand in his time, and even more so in our time. The spirit of science

is one of progress and fallibility, an open community whose only heresy

is an unwillingness to seek the truth, while the spirit of religion

includes a tendency towards conservative closure of inquiry and of

membership. While Peirce acknowledged these distinctions, he

nevertheless maintained that religion was not necessarily

opposed to science. Certain aspects of religious practice —and

especially the act of prayer—exemplify elements of inquiry. Rather than

causing thought to contract and community to become less important, as

is often supposed, practice in prayer may be a creative act, like

poetry, that can in fact lead to greater understanding of the world and

of one’s place in it. At its best, prayer arises from an instinct or

from a sentiment, and it affords comfort, strength, and—perhaps most

importantly—insight into the nature of the world...."

Read the rest here, in the latest volume of the Journal Of Scriptural Reasoning.

Read the rest here, in the latest volume of the Journal Of Scriptural Reasoning.

∞

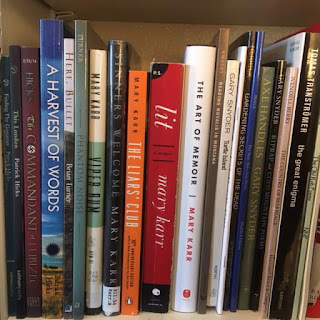

The Slow, Important Work Of Poetry

At the time it seemed like chance that brought me to minor in comparative poetry in college.

Without having a master plan, over four years I wound up taking a number of poetry classes in four languages. Eventually I asked my college to consider them a new minor area of study. They agreed, and I graduated.

And then, slowly, over a quarter century, I began reading more poetry in more languages. It's always slow; I can't pick up a book of poems and read it like a novel. If the poetry is any good at all, I can read one or two poems, and then I've got to put the book down and let the words sit with me.

Often, I go back and read the same poem again, and again.

The very best poems I try to memorize, even though my memory for verse has never been good. I imagine most people would consider that a useless exercise, a waste of storage space in an already cluttered brain.

But in each season of my life I've found that it is some form of poetry that acts as salve to my soul's wounds or food that sustains its long journey forward. Homer's long story-poems; old epics and sagas from Ireland and Wales and Iceland; Vedic verses and Greek scriptures; Gregorian chants that have echoed in stone chambers for centuries; Shakespeare's or Petrarch's sonnets; the Psalms and proverbs of Hebrew priests and kings; a few words put together well by Dylan Thomas, Gary Snyder, Tomas Tranströmer, or C.S. Lewis; or the timely phrases of some of my favorite contemporaries like Patrick Hicks, Abigail Carroll, Mary Karr, Wendell Berry, Melissa Kwasny, John Lane, or Brian Turner. Each of them has, at some point, given me the daily bread I craved.

I can't seem to predict when the need will arise, but suddenly, there it is, and I find myself quoting Joachim du Bellay's sonnet about travel, and home:

That sonnet often reminds me, in turn, of verses about Abraham.

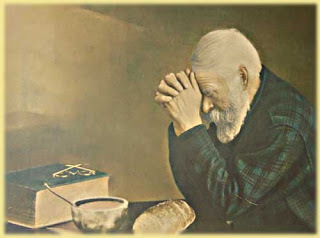

I am no good at praying, but I often wish I were. I think the fact that we make light of prayer - both by mocking those who pray and by being those who speak piously of prayer but who do not allow ourselves to confess the weakness prayer implies - says something of another shared longing, not unlike the longing for home. We long to comfort those far away when tragic events fall on them. They may be total strangers, but we know how horrible we would feel in their place, and we know that right now there is nothing we can do to staunch the flow of pain for them. But we can hold them in the center of our consciousness and, for a little while, not let any lesser thoughts crowd them out of our hearts and minds. We can, for a little while, consider our lives to be connected to theirs. We can, for a little while, ask ourselves what we might do to change the world so that this pain will not be inflicted on others.

Since I am not adept at praying, In those times I find the prayers of others buoy me up above the waves of emotional tempest. The prayer books of my tradition - the various versions of The Book of Common Prayer - often transform my anguish into something articulate. Of course, we turn to that same book when a baby is born, when a couple is wed, and when our beloved are interred. These events? We know they are coming, and yet it is not easy to prepare oneself, to be always ready for those days. I live in a tent; poetry often gives me a foundation to build on, and the better I've memorized it, the stronger that foundation becomes.

Those words, buried like seeds, slowly come to bear fruit in my life. Sometimes I wonder: was it really chance that brought me to the poems?

In the hardest of times, and also in the most joyful times, the words of poets are like a cup of water in a dry place. They refresh me, and they clear my throat so that I can take in that which sustains my own life, and speak other words, both old and new, that may sustain the lives of others.

Without having a master plan, over four years I wound up taking a number of poetry classes in four languages. Eventually I asked my college to consider them a new minor area of study. They agreed, and I graduated.

And then, slowly, over a quarter century, I began reading more poetry in more languages. It's always slow; I can't pick up a book of poems and read it like a novel. If the poetry is any good at all, I can read one or two poems, and then I've got to put the book down and let the words sit with me.

Often, I go back and read the same poem again, and again.

The very best poems I try to memorize, even though my memory for verse has never been good. I imagine most people would consider that a useless exercise, a waste of storage space in an already cluttered brain.

But in each season of my life I've found that it is some form of poetry that acts as salve to my soul's wounds or food that sustains its long journey forward. Homer's long story-poems; old epics and sagas from Ireland and Wales and Iceland; Vedic verses and Greek scriptures; Gregorian chants that have echoed in stone chambers for centuries; Shakespeare's or Petrarch's sonnets; the Psalms and proverbs of Hebrew priests and kings; a few words put together well by Dylan Thomas, Gary Snyder, Tomas Tranströmer, or C.S. Lewis; or the timely phrases of some of my favorite contemporaries like Patrick Hicks, Abigail Carroll, Mary Karr, Wendell Berry, Melissa Kwasny, John Lane, or Brian Turner. Each of them has, at some point, given me the daily bread I craved.

I can't seem to predict when the need will arise, but suddenly, there it is, and I find myself quoting Joachim du Bellay's sonnet about travel, and home:

Heureux qui, comme Ulysse, a fait un beau voyage

Ou comme cestuy-là qui conquit la toison

Et puis est retourné, plein d'usage et raison

Vivre entre ses parents le reste de son âgeHis simple words save me from forming new ones and free me to think and feel as the occasion demands; his words give utterance to what I find welling up inside me. His words change my homesickness into a stage in a worthwhile journey. Here is a very loose translation of those lines: "Happy is he who, like Ulysses, made a beautiful journey, or like that man who seized the Golden Fleece, and then traveled home again, full of wisdom, to live the rest of his life with his family." We are pulled in both directions at once: towards the Golden Fleece and adventures in Troy, and towards the home we left behind when we departed on our quest.

That sonnet often reminds me, in turn, of verses about Abraham.

Consider Abraham, who dwelled in tents,

because he was looking forward to a city with foundations.This longing for home that I sometimes have when I travel is itself no alien in any land. We all may feel it in any place. Everyone feels lost sometimes. Knowing that others have found words to express their feeling of being lost is itself a reminder that we are not alone. Hölderlin's opening words in his poem about St. John's exile on Patmos say this well:

Nah ist, und schwer zu fassen, der GottIt does seem that God - like home and family and love and neighbors - is close enough to grasp, so close that we could meaningfully touch them all right now. And yet so far that nothing but our words can draw near.

I am no good at praying, but I often wish I were. I think the fact that we make light of prayer - both by mocking those who pray and by being those who speak piously of prayer but who do not allow ourselves to confess the weakness prayer implies - says something of another shared longing, not unlike the longing for home. We long to comfort those far away when tragic events fall on them. They may be total strangers, but we know how horrible we would feel in their place, and we know that right now there is nothing we can do to staunch the flow of pain for them. But we can hold them in the center of our consciousness and, for a little while, not let any lesser thoughts crowd them out of our hearts and minds. We can, for a little while, consider our lives to be connected to theirs. We can, for a little while, ask ourselves what we might do to change the world so that this pain will not be inflicted on others.

Since I am not adept at praying, In those times I find the prayers of others buoy me up above the waves of emotional tempest. The prayer books of my tradition - the various versions of The Book of Common Prayer - often transform my anguish into something articulate. Of course, we turn to that same book when a baby is born, when a couple is wed, and when our beloved are interred. These events? We know they are coming, and yet it is not easy to prepare oneself, to be always ready for those days. I live in a tent; poetry often gives me a foundation to build on, and the better I've memorized it, the stronger that foundation becomes.

Those words, buried like seeds, slowly come to bear fruit in my life. Sometimes I wonder: was it really chance that brought me to the poems?

In the hardest of times, and also in the most joyful times, the words of poets are like a cup of water in a dry place. They refresh me, and they clear my throat so that I can take in that which sustains my own life, and speak other words, both old and new, that may sustain the lives of others.

∞

A Visible Sign

This morning my wife, my kids, and I sat around the Christmas tree and opened the gifts we gave one another. Just as we were finishing, my wife's phone rang.

One of her parishioners was coming down from a bad high in a bad way. The police were on the scene, and the whole family was understandably distressed.

I don't know many details, because as a priest she has to keep confidences. All I know is that her parishioners were asking for her to come and help before things got out of hand.

I don't know many details, because as a priest she has to keep confidences. All I know is that her parishioners were asking for her to come and help before things got out of hand.

Which raises the question, "How can a minister possibly help?" She hasn't got a badge or a gun, so she can't arrest people and lock them up; she doesn't have a medical license, so she can't prescribe medications; she isn't a judge who can order someone to be placed in protective custody.

All she can do is be present with those who are suffering. She can listen to those to whom no one else will listen. She can pray with them, helping to connect those who are suffering with words to express that suffering. She can deliver the sacrament, a visible and outward sign of indelible connection to a bigger community, reminding the lonely that they are not alone.

She quickly got out of her pajamas, put on a black shirt and her clerical collar, and picked up her Book of Common Prayer. I kissed her before she went out the door, aware that she was going to a home where there was a troubled family, a belligerent drug user, and eight armed men charged with upholding the law. Oh, boy. "Do you want some company?" I asked, knowing there wasn't much I could offer besides that. She said she'd be fine.

As she left, and the kids continued to examine their gifts, I sat and silently prayed (reluctantly, as always), joining her in her work in that small way.

I admit that I do not like church. I can think of far pleasanter ways to spend my Sunday morning than leaving my house to stand, and sit, and kneel with a hundred relative strangers.

But this is one thing I love about churches: this deeply democratic commitment to including everyone in the community. No one is to be left out. No one gets more bread or more wine at the altar. Everyone who needs solace, or penance, or forgiveness, or company, may have it.

The Book Of The Acts Of The Apostles, the fifth book of the Greek testament, tells the story of the early church as a place where people who needed food or money or other kinds of sustenance could come and find them. Early on in that book we even see the story of how the church made a special office for people whose job it would be to oversee the equitable distribution of food to the poor.

I think highly of my own profession of teaching, because I think it serves a high social good. But I teach in a small, selective liberal arts college. Most of the people I serve have their lives pretty much together. In general, they can pay their bills, they don't have huge drug or legal issues, they have supportive communities, they can think and write well. Yes, most of them struggle with money and other things, but they keep their heads above water, and their futures are bright.

My wife, on the other hand, has a much broader "clientele." She serves the congregations at our cathedral and several other parishes. Her congregants range from the powerful and wealthy to the poorest of the poor. Here in South Dakota more than half our diocese are Native Americans, and many more are refugees from conflicts in east Africa. Ethnically, racially, economically, liturgically, and politically, this is a diverse group.

And again, it is a group where everyone is - or at least ought to be - welcome.

The church has always failed to live up to its ideals. I don't dispute that. Show me an institution that has good ideals and that always lives up to them, and I'll readily tip my hat to it. What I love in the church is that it has these ideals and it has daily, weekly, and annual rituals by which we remind ourselves what those ideals are. We screw them up, we distort and bastardize them, we even sell them to high bidders from time to time when we lose our heads and our hearts. But then we remind ourselves that we should not. And we have institutions and rituals of returning to the path we've departed from.

We will probably always get it wrong. I'm okay with that, as long as we keep turning back towards what is right, as long as we maintain these traditions and rituals of self-examination and self-correction. And as long as we cherish this ideal of welcoming everyone, absolutely everyone. I don't mean just saying we welcome everyone, but I mean doing it.

Again, I work at a small college. Colleges are places where we all talk a good game about being welcoming, and for the most part, we manage to practice what we preach, given the communities we work in. But there's something really remarkable about seeing that ideal at work in a community where there are no grades and no graduation, where the congregation is not just 18-22 year-olds with high entrance exam scores, and where no one gets kicked out for failure to live up to the ideals of the place.

Last night we celebrated Christmas with hymns in two languages.

My wife came home a hour or so after she left this morning. I don't worry so much about her sudden comings and goings as I once did. She gets calls late at night from broken-hearted families watching their beloved die in our hospitals. Will she come and pray with them? Will she come hold their hands for a little while, and be the vicarious presence of the whole church as they suffer? Will she anoint the sick as a reminder of our shared hope for well-being for all people? Will she come to the jail to talk with the kid who has just been arrested, or to sit with his frightened parents? Will she come to the nursing home where they're wondering if this is the last holiday a grandparent will see?

Yes, she will. This is her calling, the work she has been ordained to do. It is the work of love, and I love her for it.

As she walked in the door, I was going to greet her when her phone rang again. I recognized from her conversation that it is a parishioner with memory problems who calls her almost every day to ask the same questions. Sometimes it seems he has been drinking; most of the time it seems he is lonely and afraid. I knew my greeting could wait, and as she patiently listened to her parishioner, I joined her in silent prayer, thanking God for the kindness she shows and represents, a visible sign of the ideal of our community. She cheerfully wished him a Merry Christmas. I think she was glad he knew what day it was.

I don't know how she does it, but she makes me want to keep trying.

One of her parishioners was coming down from a bad high in a bad way. The police were on the scene, and the whole family was understandably distressed.

I don't know many details, because as a priest she has to keep confidences. All I know is that her parishioners were asking for her to come and help before things got out of hand.

I don't know many details, because as a priest she has to keep confidences. All I know is that her parishioners were asking for her to come and help before things got out of hand.Which raises the question, "How can a minister possibly help?" She hasn't got a badge or a gun, so she can't arrest people and lock them up; she doesn't have a medical license, so she can't prescribe medications; she isn't a judge who can order someone to be placed in protective custody.

All she can do is be present with those who are suffering. She can listen to those to whom no one else will listen. She can pray with them, helping to connect those who are suffering with words to express that suffering. She can deliver the sacrament, a visible and outward sign of indelible connection to a bigger community, reminding the lonely that they are not alone.

She quickly got out of her pajamas, put on a black shirt and her clerical collar, and picked up her Book of Common Prayer. I kissed her before she went out the door, aware that she was going to a home where there was a troubled family, a belligerent drug user, and eight armed men charged with upholding the law. Oh, boy. "Do you want some company?" I asked, knowing there wasn't much I could offer besides that. She said she'd be fine.

As she left, and the kids continued to examine their gifts, I sat and silently prayed (reluctantly, as always), joining her in her work in that small way.

I admit that I do not like church. I can think of far pleasanter ways to spend my Sunday morning than leaving my house to stand, and sit, and kneel with a hundred relative strangers.

But this is one thing I love about churches: this deeply democratic commitment to including everyone in the community. No one is to be left out. No one gets more bread or more wine at the altar. Everyone who needs solace, or penance, or forgiveness, or company, may have it.

The Book Of The Acts Of The Apostles, the fifth book of the Greek testament, tells the story of the early church as a place where people who needed food or money or other kinds of sustenance could come and find them. Early on in that book we even see the story of how the church made a special office for people whose job it would be to oversee the equitable distribution of food to the poor.

I think highly of my own profession of teaching, because I think it serves a high social good. But I teach in a small, selective liberal arts college. Most of the people I serve have their lives pretty much together. In general, they can pay their bills, they don't have huge drug or legal issues, they have supportive communities, they can think and write well. Yes, most of them struggle with money and other things, but they keep their heads above water, and their futures are bright.

My wife, on the other hand, has a much broader "clientele." She serves the congregations at our cathedral and several other parishes. Her congregants range from the powerful and wealthy to the poorest of the poor. Here in South Dakota more than half our diocese are Native Americans, and many more are refugees from conflicts in east Africa. Ethnically, racially, economically, liturgically, and politically, this is a diverse group.

And again, it is a group where everyone is - or at least ought to be - welcome.

The church has always failed to live up to its ideals. I don't dispute that. Show me an institution that has good ideals and that always lives up to them, and I'll readily tip my hat to it. What I love in the church is that it has these ideals and it has daily, weekly, and annual rituals by which we remind ourselves what those ideals are. We screw them up, we distort and bastardize them, we even sell them to high bidders from time to time when we lose our heads and our hearts. But then we remind ourselves that we should not. And we have institutions and rituals of returning to the path we've departed from.

We will probably always get it wrong. I'm okay with that, as long as we keep turning back towards what is right, as long as we maintain these traditions and rituals of self-examination and self-correction. And as long as we cherish this ideal of welcoming everyone, absolutely everyone. I don't mean just saying we welcome everyone, but I mean doing it.

Again, I work at a small college. Colleges are places where we all talk a good game about being welcoming, and for the most part, we manage to practice what we preach, given the communities we work in. But there's something really remarkable about seeing that ideal at work in a community where there are no grades and no graduation, where the congregation is not just 18-22 year-olds with high entrance exam scores, and where no one gets kicked out for failure to live up to the ideals of the place.

Last night we celebrated Christmas with hymns in two languages.

Hanhepi wakan kin!That's the second verse of "Silent Night, Holy Night," from the Dakota Episcopal hymnal. We sing the doxology in Dakota, and I'm happy to say that most of the white folks at several congregations in the area have it memorized in Dakota. These are small things, but they might also be big things. If the baby Christ was the Word incarnate, surely little words can make a big difference.

Wonahon wotanin

Mahpiyata wowitan,

On Wakantanka yatanpi.

Christ Wanikiya hi!

My wife came home a hour or so after she left this morning. I don't worry so much about her sudden comings and goings as I once did. She gets calls late at night from broken-hearted families watching their beloved die in our hospitals. Will she come and pray with them? Will she come hold their hands for a little while, and be the vicarious presence of the whole church as they suffer? Will she anoint the sick as a reminder of our shared hope for well-being for all people? Will she come to the jail to talk with the kid who has just been arrested, or to sit with his frightened parents? Will she come to the nursing home where they're wondering if this is the last holiday a grandparent will see?

Yes, she will. This is her calling, the work she has been ordained to do. It is the work of love, and I love her for it.

As she walked in the door, I was going to greet her when her phone rang again. I recognized from her conversation that it is a parishioner with memory problems who calls her almost every day to ask the same questions. Sometimes it seems he has been drinking; most of the time it seems he is lonely and afraid. I knew my greeting could wait, and as she patiently listened to her parishioner, I joined her in silent prayer, thanking God for the kindness she shows and represents, a visible sign of the ideal of our community. She cheerfully wished him a Merry Christmas. I think she was glad he knew what day it was.

I don't know how she does it, but she makes me want to keep trying.

∞

The Best Break-Up Ever

Last week my oncologist broke up with me. It was the best break-up ever.

Fifteen years ago I got a call from my doctor. He asked me, "Are you sitting down?" Then he added, "I have some bad news from your tests." Two days later I was in surgery having a tumor removed.

Our kids were small, we were young, and I was in my second year of grad school at St. John's College. I earned an hourly wage as a substitute teacher at a local prep school, which I supplemented by teaching Spanish to a group of kindergarteners, giving Greek lessons to a high school student, and occasionally working as a fly-fishing guide in northern New Mexico. Like many graduate students, we lived far below the poverty level. We were fortunate to have basic health insurance, supportive families, WIC, and a great local church. Even so, we knew we had an uncertain road ahead.

Since then we've moved twice, I finished grad school at Penn State, and have been awarded tenure at a fine liberal arts college in South Dakota, Augustana College.

And over the years I've lost track of how many times I've been stuck with needles or made to swallow barium sulfate contrast. Each time I drink that stuff it's worse than the last time. It makes me feel like it's stripping my intestines of their very lining. At first I could go to work afterwards, but the last few times I've had it it has left me too weak to walk for much of the day.

Who knows how much iodine radiocontrast I've had injected into my veins? You feel it enter your vein, and the mild burn pulses, lub-dub, with each heartbeat, up your arm and then crashes into your heart. A moment after it hits your heart, it explodes outward across your whole body. It shoots up your neck, setting your throat abuzz, and then you taste metal. At the same time it rushes downward and you feel like you've just wet your pants. (I'm told many people do in fact become incontinent at this point.)

I've taken it all more or less in stride, because, as they say, fighting cancer beats the alternative. In some ways, it was probably easier for me than for my family, since there wasn't much I could do about it other than submit to the treatment, and when I did, it left me too weak for worry. My wife was nothing short of amazing when I was first diagnosed, taking care of three small kids and one sick husband. She has a long and deep habit of prayer, and I think that was her sea anchor in a rough storm.

Each time we've moved I've had to find a new oncologist, and again, I've been fortunate to find good ones, serious physicians who really showed concern for me. (Michael McHale in Sioux Falls always took the time to ask me about my life before he asked me about my body, and I am grateful for him like I am grateful for friends and ministers and counselors. Our insurance wouldn't let me keep seeing him, unfortunately, so I've had a few other oncologists over the last three years.)

Last week, my current oncologist and I looked over my medical history together. It's an annual ritual: we look at my tumor markers and my other bloodwork, my most recent X-rays or CT scan. The doctor nods and says that nothing has changed, and he'll see me again in six months or a year.

This time, it was different. "It has been fifteen years, and we haven't seen any new tumors," he said. "It's possible that it will recur, of course. You're in a higher risk group, and there could be some cells in some other part of your body that are slowly growing." I'm used to hearing this, so I nodded, and looked in his eyes as I always do, to see if there's news I should brace myself for.

Having cancer at a young age was like an early midlife crisis. It sharpened my focus and made me see that there was no point wasting whatever time I have left. If there is something I should be doing, now is the time to do it, not later. I'm trying to live fully now, not postponing life until I feel more rested, or more financially sound, or more ready for it. I don't think I'm being reckless, but I'm trying to live well, and without regrets. The days of my life are numbered, but I am unable to count any of them but the ones in the past, plus today.

It's not like I spend a lot of time thinking about my own mortality, mind you. But every visit to the oncologist is a reminder that I am still alive. My first oncologist told me, "you drew the historical long straw," explaining that only twenty years earlier my cancer was one of the least curable forms, but thanks to recent research it was now one of the most curable.

(As an aside, thanks for giving to that research, and please keep giving to organizations like the American Cancer Society. I advise the Augustana College Chapter of Colleges Against Cancer, so I'd be remiss if I didn't put that in here!)

"But everything looks good. I don't think you need to come back, as long as you and your regular doctor keep checking for lumps."

I think I must have looked like a cow staring at a new gate*, or a deer caught in the headlights. He smiled at me. "If you're okay with that, I mean."

"Yes, I'm okay with that," I stammered.

"Then we're graduating you. No need to come back," he said. He extended his hand to shake mine, and then he and his resident, congratulating me, left me to consider a life without coming back to his office.

I've lost a lot of friends and family to cancer, including my beautiful, wonderful mother. A number of my friends and colleagues or their spouses are afflicted by rogue cells in their bodies right now. It's a frightening, ugly thing to hear your body is growing itself out of its own orderly bounds, that some part of you is growing towards death, that your body has become entangled with a worse form of itself that threatens to overshadow all that is good in you.

So for now, I am still basking in the warmth of this best break-up ever. I'm glad to hear my oncologist has dumped me. I'm delighted to hear that those misfiring cell divisions have been banished from my body.

And I'm hoping that more and more people who long for such news will come to hear it soon, mindful that many who deserve to hear it never will.

Now, if you will excuse me, I have a fresh today to attend to.

* This is from Martin Luther. He writes, wie ein kue ein neues thor ansihet.

Fifteen years ago I got a call from my doctor. He asked me, "Are you sitting down?" Then he added, "I have some bad news from your tests." Two days later I was in surgery having a tumor removed.

Our kids were small, we were young, and I was in my second year of grad school at St. John's College. I earned an hourly wage as a substitute teacher at a local prep school, which I supplemented by teaching Spanish to a group of kindergarteners, giving Greek lessons to a high school student, and occasionally working as a fly-fishing guide in northern New Mexico. Like many graduate students, we lived far below the poverty level. We were fortunate to have basic health insurance, supportive families, WIC, and a great local church. Even so, we knew we had an uncertain road ahead.

Since then we've moved twice, I finished grad school at Penn State, and have been awarded tenure at a fine liberal arts college in South Dakota, Augustana College.

And over the years I've lost track of how many times I've been stuck with needles or made to swallow barium sulfate contrast. Each time I drink that stuff it's worse than the last time. It makes me feel like it's stripping my intestines of their very lining. At first I could go to work afterwards, but the last few times I've had it it has left me too weak to walk for much of the day.

Who knows how much iodine radiocontrast I've had injected into my veins? You feel it enter your vein, and the mild burn pulses, lub-dub, with each heartbeat, up your arm and then crashes into your heart. A moment after it hits your heart, it explodes outward across your whole body. It shoots up your neck, setting your throat abuzz, and then you taste metal. At the same time it rushes downward and you feel like you've just wet your pants. (I'm told many people do in fact become incontinent at this point.)

I've taken it all more or less in stride, because, as they say, fighting cancer beats the alternative. In some ways, it was probably easier for me than for my family, since there wasn't much I could do about it other than submit to the treatment, and when I did, it left me too weak for worry. My wife was nothing short of amazing when I was first diagnosed, taking care of three small kids and one sick husband. She has a long and deep habit of prayer, and I think that was her sea anchor in a rough storm.

Each time we've moved I've had to find a new oncologist, and again, I've been fortunate to find good ones, serious physicians who really showed concern for me. (Michael McHale in Sioux Falls always took the time to ask me about my life before he asked me about my body, and I am grateful for him like I am grateful for friends and ministers and counselors. Our insurance wouldn't let me keep seeing him, unfortunately, so I've had a few other oncologists over the last three years.)

Last week, my current oncologist and I looked over my medical history together. It's an annual ritual: we look at my tumor markers and my other bloodwork, my most recent X-rays or CT scan. The doctor nods and says that nothing has changed, and he'll see me again in six months or a year.

This time, it was different. "It has been fifteen years, and we haven't seen any new tumors," he said. "It's possible that it will recur, of course. You're in a higher risk group, and there could be some cells in some other part of your body that are slowly growing." I'm used to hearing this, so I nodded, and looked in his eyes as I always do, to see if there's news I should brace myself for.

Having cancer at a young age was like an early midlife crisis. It sharpened my focus and made me see that there was no point wasting whatever time I have left. If there is something I should be doing, now is the time to do it, not later. I'm trying to live fully now, not postponing life until I feel more rested, or more financially sound, or more ready for it. I don't think I'm being reckless, but I'm trying to live well, and without regrets. The days of my life are numbered, but I am unable to count any of them but the ones in the past, plus today.

It's not like I spend a lot of time thinking about my own mortality, mind you. But every visit to the oncologist is a reminder that I am still alive. My first oncologist told me, "you drew the historical long straw," explaining that only twenty years earlier my cancer was one of the least curable forms, but thanks to recent research it was now one of the most curable.

(As an aside, thanks for giving to that research, and please keep giving to organizations like the American Cancer Society. I advise the Augustana College Chapter of Colleges Against Cancer, so I'd be remiss if I didn't put that in here!)

"But everything looks good. I don't think you need to come back, as long as you and your regular doctor keep checking for lumps."

I think I must have looked like a cow staring at a new gate*, or a deer caught in the headlights. He smiled at me. "If you're okay with that, I mean."

"Yes, I'm okay with that," I stammered.

"Then we're graduating you. No need to come back," he said. He extended his hand to shake mine, and then he and his resident, congratulating me, left me to consider a life without coming back to his office.

I've lost a lot of friends and family to cancer, including my beautiful, wonderful mother. A number of my friends and colleagues or their spouses are afflicted by rogue cells in their bodies right now. It's a frightening, ugly thing to hear your body is growing itself out of its own orderly bounds, that some part of you is growing towards death, that your body has become entangled with a worse form of itself that threatens to overshadow all that is good in you.

So for now, I am still basking in the warmth of this best break-up ever. I'm glad to hear my oncologist has dumped me. I'm delighted to hear that those misfiring cell divisions have been banished from my body.

And I'm hoping that more and more people who long for such news will come to hear it soon, mindful that many who deserve to hear it never will.

Now, if you will excuse me, I have a fresh today to attend to.

**********

* This is from Martin Luther. He writes, wie ein kue ein neues thor ansihet.

∞

Giving Our Prayers Feet

The American scientist and philosopher Charles Peirce described belief as an idea you are prepared to act on. If you say you believe something but you are not prepared to act on it, you probably don't really believe it in any meaningful sense of that word.

Of course, there might be a number of ways in which we might act on our beliefs.

What about prayer? Could praying be a kind of action?

It depends.

Philosopher and atheist Daniel Dennett once described prayer as a waste of time. I mean literally a waste of time. If you're praying, he said, you're not engaged in useful activity. When he was ill, someone offered to pray for him. His reply:

On the other hand, as I've argued before, prayer might be essential to other kinds of action.

Giving our money and time is generally a good thing, I think, but I think the giving becomes deeper still when we do as Thoreau urged in Walden: don't just give your money, but give yourself. In other words, if you've begun by dumping water on your head for an ALS icebucket challenge, great. Now deepen that giving by making it part of who you are.

If you decide to do that, prayer - or something like it, I don't care what you call it - can make a big difference. Here's what I mean: giving to charities can be automated, so you can do it without thinking about it. Set up an automatic bank transfer each month and you can give to as many charities as you can afford, without putting much of yourself in it. But if you make those philanthropies and missions the intentional object of your thought for part of each day, you might find that you begin to care a lot more about the cause and the people involved.

If praying is the act of giving some of your time to bring together the world's greatest needs and your greatest hopes, then prayer might be the most important thing we can do. Too often we allow ourselves to divorce others' needs from our hopes, and then the needs of others become allied with our fears.

This is one reason why I respond to the news each day with prayer. Sometimes my prayers are simply Kyrie eleison, "Lord, have mercy." Because sometimes that's all I've got when my heart and mind are overwhelmed. But if that's all I've got, then it will be my widow's mite, and I'll give it. By the way, this has the added effect of making me worry less without taking away my desire to act for goodness and justice.

(My friend Anna Madsen has a short, funny, and helpful piece about just that, by the way. Check it out here.)

All of this was inspired by a moving Facebook post by an alumnus of my college, Caleb Rupert. Caleb is a thoughtful and creative man, and though I don't know him well, he strikes me as a good egg and as someone who wants to do the best he can in this life. Here's what he shared on his page:

I asked Caleb if I could share his words here. His reply is just as good as his original post. He said I could post his words, provided I include some links to local food shelves, soup kitchens, and homeless shelters. I love that.

So I will ask that if you share this post, you do the same thing by posting a link to at least one organization in *your* community that helps the homeless. In that way, let us make our prayers effective to the best of our ability, and may they rise to whatever heaven may be.

Here are my links for Sioux Falls, South Dakota. Please consider volunteering your time, giving your money, and remembering them and the people they serve in your prayers. And as you do so, may your prayers grow feet, and begin to change the world.

The Banquet

Union Gospel Mission

St Francis House

Of course, there might be a number of ways in which we might act on our beliefs.

What about prayer? Could praying be a kind of action?

It depends.

Philosopher and atheist Daniel Dennett once described prayer as a waste of time. I mean literally a waste of time. If you're praying, he said, you're not engaged in useful activity. When he was ill, someone offered to pray for him. His reply:

Surely it does the world no harm if those who can honestly do so pray for me! No, I'm not at all sure about that. For one thing, if they really wanted to do something useful, they could devote their prayer time and energy to some pressing project that they can do something about. (emphasis added)I agree with him that if prayer keeps us from doing what we can to alleviate the suffering of the world, we're probably using our time poorly.

On the other hand, as I've argued before, prayer might be essential to other kinds of action.

Giving our money and time is generally a good thing, I think, but I think the giving becomes deeper still when we do as Thoreau urged in Walden: don't just give your money, but give yourself. In other words, if you've begun by dumping water on your head for an ALS icebucket challenge, great. Now deepen that giving by making it part of who you are.

If you decide to do that, prayer - or something like it, I don't care what you call it - can make a big difference. Here's what I mean: giving to charities can be automated, so you can do it without thinking about it. Set up an automatic bank transfer each month and you can give to as many charities as you can afford, without putting much of yourself in it. But if you make those philanthropies and missions the intentional object of your thought for part of each day, you might find that you begin to care a lot more about the cause and the people involved.

If praying is the act of giving some of your time to bring together the world's greatest needs and your greatest hopes, then prayer might be the most important thing we can do. Too often we allow ourselves to divorce others' needs from our hopes, and then the needs of others become allied with our fears.

This is one reason why I respond to the news each day with prayer. Sometimes my prayers are simply Kyrie eleison, "Lord, have mercy." Because sometimes that's all I've got when my heart and mind are overwhelmed. But if that's all I've got, then it will be my widow's mite, and I'll give it. By the way, this has the added effect of making me worry less without taking away my desire to act for goodness and justice.

(My friend Anna Madsen has a short, funny, and helpful piece about just that, by the way. Check it out here.)

All of this was inspired by a moving Facebook post by an alumnus of my college, Caleb Rupert. Caleb is a thoughtful and creative man, and though I don't know him well, he strikes me as a good egg and as someone who wants to do the best he can in this life. Here's what he shared on his page:

I'm standing at the bus stop and on the corner is a homeless woman. A kind looking black gentleman is walking by and nearly walks past her to beak the red-hand count down, 5, 4, 3....The gentleman stops, and turns to the homeless woman. He then falls to his knees and says a short prayer; I cannot hear the words, I'm too far away. As he finishes, she looks up and smiles at him. He smiles back and crosses the street. This gentleman gave up an entire two signals to acknowledge this woman through prayer. Though I do not believe that prayer will be heard by any entity other than the person praying and those around them, this does not discount the power, and importance, of acknowledgement of something as wicked as homelessness. A challenge in which so many of us like to ignore or pretend is non-existence, or worse, pretend this challenge is not as harsh and hard as it is. Regardless of my views of the validity of religion, I cannot ignore the importance of it being an entity which can cause those that follow, truly follow, not just "Sunday believers," but those that acknowledge the importance that every prophet and god-son has preached, which is to care for those that suffer and those that struggle. This gentleman, through his beliefs, gave this woman a smile, and the knowledge that when she goes to bed at night, someone is thinking about her and cares about her well being enough to stop and give his God, which he truly devotes himself to, a mention of her. In the end, regardless of a beliefs validity, what I believe is most important is relieving the pain of those that suffer and always remember that there is always someone who hurts more than you and your acknowledgement is the thing that can save them, even for a brief second, relief from that pain. (Emphasis added)Caleb's words remind me of Thoreau's, and of Dennett's, and of Jesus's. Yeah, you read that right. Because all four of them are concerned with making sure that whatever we do, we act on what we believe, and that we act in a way that tries to make others' lives better.

I asked Caleb if I could share his words here. His reply is just as good as his original post. He said I could post his words, provided I include some links to local food shelves, soup kitchens, and homeless shelters. I love that.

So I will ask that if you share this post, you do the same thing by posting a link to at least one organization in *your* community that helps the homeless. In that way, let us make our prayers effective to the best of our ability, and may they rise to whatever heaven may be.

Here are my links for Sioux Falls, South Dakota. Please consider volunteering your time, giving your money, and remembering them and the people they serve in your prayers. And as you do so, may your prayers grow feet, and begin to change the world.

The Banquet

Union Gospel Mission

St Francis House

∞

One thing that made the sermon especially strong was its open-endedness: our priest didn't try to apply the sermon to any one social problem, as he could have. Instead, he invited all his listeners to consider whether we'd be willing to have big love remake our lives. In other words, rather than making this into a doctrinal roll-call or a chance to affirm that we all believe the same thing and then move on, unchanged, we were invited to consider, in quiet self-examination, whether we were willing to let love rule in our lives.

One thing that made the sermon especially strong was its open-endedness: our priest didn't try to apply the sermon to any one social problem, as he could have. Instead, he invited all his listeners to consider whether we'd be willing to have big love remake our lives. In other words, rather than making this into a doctrinal roll-call or a chance to affirm that we all believe the same thing and then move on, unchanged, we were invited to consider, in quiet self-examination, whether we were willing to let love rule in our lives.

Part of me really doesn't like church. There's so much about it that bores me, and I usually like sermons least of all. And when I'm not bored, I'm often surrounded by people I don't know very well, shaking my hand and passing a sign of peace. It's an introvert-germophobe's introduction to the doctrine of hell, I guess, so it does serve that theological purpose. I'd prefer a quick nod, some formal bowing, a lot of incense and some well-tuned bells, but you can't always get what you want.

Part of me really doesn't like church. There's so much about it that bores me, and I usually like sermons least of all. And when I'm not bored, I'm often surrounded by people I don't know very well, shaking my hand and passing a sign of peace. It's an introvert-germophobe's introduction to the doctrine of hell, I guess, so it does serve that theological purpose. I'd prefer a quick nod, some formal bowing, a lot of incense and some well-tuned bells, but you can't always get what you want.

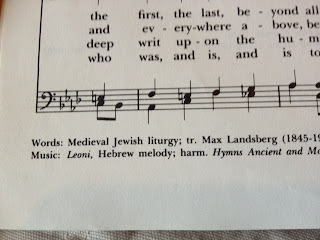

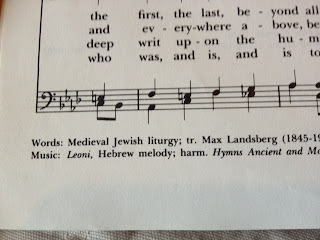

This morning was a pretty good morning. Not only did I hear that excellent sermon that will provide food for thought all week, we also sang a hymn that was translated from a Medieval Hebrew liturgy. Good hymnals and prayerbooks can be bouquets of the choicest flowers of religious poetry. The Book of Common Prayer has often rescued my anguished mind when it cannot find words. Often, when I sing hymns to the room-filling sound of a well-played pipe organ, I find myself wondering how people who do not have a congregation to sing with find opportunities to sing with others. That probably sounds judgmental, but I don't mean it to. I just wish there were more songs sung by people in our daily lives. I suspect the near-universal ownership of iPods is a result of the vanishing tradition of singing together.

This morning was a pretty good morning. Not only did I hear that excellent sermon that will provide food for thought all week, we also sang a hymn that was translated from a Medieval Hebrew liturgy. Good hymnals and prayerbooks can be bouquets of the choicest flowers of religious poetry. The Book of Common Prayer has often rescued my anguished mind when it cannot find words. Often, when I sing hymns to the room-filling sound of a well-played pipe organ, I find myself wondering how people who do not have a congregation to sing with find opportunities to sing with others. That probably sounds judgmental, but I don't mean it to. I just wish there were more songs sung by people in our daily lives. I suspect the near-universal ownership of iPods is a result of the vanishing tradition of singing together.

Can I Ask Questions In Church?

Today I heard a thoughtful, thought-provoking sermon about St Paul's Epistle to Philemon. The heart of it was this: Paul urged Philemon not to claim his legal right, but to lay aside his rights for the sake of the big love that wants to remodel his whole life.

Nobody in their right mind wants that.

Which is why Paul describes that big love elsewhere as foolishness to Greeks - and, he might have added, to anyone else who takes reason seriously.

After all, it's a little bit crazy to lay aside your legal rights for the sake of others. In Philemon's case, Paul was asking him to:

*****

One thing that made the sermon especially strong was its open-endedness: our priest didn't try to apply the sermon to any one social problem, as he could have. Instead, he invited all his listeners to consider whether we'd be willing to have big love remake our lives. In other words, rather than making this into a doctrinal roll-call or a chance to affirm that we all believe the same thing and then move on, unchanged, we were invited to consider, in quiet self-examination, whether we were willing to let love rule in our lives.

One thing that made the sermon especially strong was its open-endedness: our priest didn't try to apply the sermon to any one social problem, as he could have. Instead, he invited all his listeners to consider whether we'd be willing to have big love remake our lives. In other words, rather than making this into a doctrinal roll-call or a chance to affirm that we all believe the same thing and then move on, unchanged, we were invited to consider, in quiet self-examination, whether we were willing to let love rule in our lives.

This is like Mary's approach in John's Gospel, when she tells Jesus "They have no more wine," then tells the servants, "Do whatever he says." She knows enough to know that she doesn't know all the answers. I think our priest was saying something similar today: he doesn't know all the answers, but he's committed to big love, and was inviting us to consider whether we also share that confidence.

To put it differently, he left us with a question to mull over for the week.

Which is often far more helpful than being left with an answer.

*****

Part of me really doesn't like church. There's so much about it that bores me, and I usually like sermons least of all. And when I'm not bored, I'm often surrounded by people I don't know very well, shaking my hand and passing a sign of peace. It's an introvert-germophobe's introduction to the doctrine of hell, I guess, so it does serve that theological purpose. I'd prefer a quick nod, some formal bowing, a lot of incense and some well-tuned bells, but you can't always get what you want.

Part of me really doesn't like church. There's so much about it that bores me, and I usually like sermons least of all. And when I'm not bored, I'm often surrounded by people I don't know very well, shaking my hand and passing a sign of peace. It's an introvert-germophobe's introduction to the doctrine of hell, I guess, so it does serve that theological purpose. I'd prefer a quick nod, some formal bowing, a lot of incense and some well-tuned bells, but you can't always get what you want.

But you do often get what you need, and I think of church the way I think of prayer, or aerobic exercise, or dietary fiber: I need them. Even, and perhaps especially, when I don't want them. And when they are a part of my life, my life feels more whole.

This can be hard to explain to others, so I understand if you think I go to church because it makes me feel good, or because my culture has made it hard for me to think of doing otherwise, or because I feel guilty when I don't go.

I actually feel pretty good when I don't go to church, just like I feel pretty good when I decide to write a blog post instead of going on that four-mile run I had planned.

And so often, when I attend churches, I hear or see things I wish I hadn't heard or seen. These congregations founded on the worship of big love can become gardens overrun by the weeds of uncharitable hearts; some "hymns" I hear are schmaltzy or foolish, or unintentionally (I hope!) promote slavish and unkind ideas about race or gender. At times like that, I'm tempted to give up on "organized" religion altogether.

*****

This morning was a pretty good morning. Not only did I hear that excellent sermon that will provide food for thought all week, we also sang a hymn that was translated from a Medieval Hebrew liturgy. Good hymnals and prayerbooks can be bouquets of the choicest flowers of religious poetry. The Book of Common Prayer has often rescued my anguished mind when it cannot find words. Often, when I sing hymns to the room-filling sound of a well-played pipe organ, I find myself wondering how people who do not have a congregation to sing with find opportunities to sing with others. That probably sounds judgmental, but I don't mean it to. I just wish there were more songs sung by people in our daily lives. I suspect the near-universal ownership of iPods is a result of the vanishing tradition of singing together.

This morning was a pretty good morning. Not only did I hear that excellent sermon that will provide food for thought all week, we also sang a hymn that was translated from a Medieval Hebrew liturgy. Good hymnals and prayerbooks can be bouquets of the choicest flowers of religious poetry. The Book of Common Prayer has often rescued my anguished mind when it cannot find words. Often, when I sing hymns to the room-filling sound of a well-played pipe organ, I find myself wondering how people who do not have a congregation to sing with find opportunities to sing with others. That probably sounds judgmental, but I don't mean it to. I just wish there were more songs sung by people in our daily lives. I suspect the near-universal ownership of iPods is a result of the vanishing tradition of singing together.

When I came home I saw that a friend had tagged me in a post on Facebook, where she shared this article about the importance of continuing to ask big questions. To which I say "amen."

The article raises just this question of whether a decline in attendance at religious services decreases the places in which can we ask big questions:

The article raises just this question of whether a decline in attendance at religious services decreases the places in which can we ask big questions:

"“For anyone who goes to church, these are the questions they are essentially grappling with via their faith,” said Brooks. Indeed, a measurable drop in religious affiliation and attendance at houses of worship may be a factor in the decline of a culture of inquiry and conversation."

I don't know if that's true, and I don't want to claim that the sky is falling because the pews aren't full. But I do find that sitting in the pew helps me, and I think it could be more helpful to more people if there were more sermons like the one I heard today. It's good to ask questions together, and to let the questions do their work.

So I hope that more of us who think that meeting together to pray and sing and reflect on what we believe is a worthwhile practice will do as our priest did this morning, inviting others to turn with him to reflect on the big questions, and the big ideas, and the big love, that - in my case, at least - can keep us from living unexamined lives.

∞

Pornography and Prayer

A recent Wall Street Journal article talks about the way online pornography quickly develops new neural pathways that are difficult to undo. As the author puts it,

To put it differently, everyone worships something, and what we worship changes us. This is one of the good reasons to engage in prayer and worship that are intentional. (On a related note, it's a good reason to forgive, too: forgiveness keeps us from internalizing the pain others have caused us, where it can fester and devour us from within.)

(If you read my writing with any regularity you will recognize these as themes I frequently return to. If you're interested, I've written more here and here.)

One of the problems of philosophy of religion has been to try to identify that which certainly deserves our worship. This quest for certainty has often (in my view) distracted us from the more important work of liturgy, wherein we acknowledge our limitations, including our uncertainty. A good liturgy involves worshiping what we believe to be worth worshiping, while acknowledging our own limitations. After all, if worship doesn't include humility on the part of the worshiper, it is probably self-worship.

Another way of putting this is in terms of love. Charles Peirce wrote about this more than a century ago. There are many forms of worship, many kinds of prayer. Without intending to demean the prayer and worship of others, Peirce nevertheless offers what seems to him to be worth our attention: agape love, the love that seeks to nurture others:

I am not trying to moralize about pornography. In fact, I see some good in pornography, just as I recognize goodness in the aromas coming from a kitchen where good cooking happens. Pornography probably speaks to some of our most basic desires and needs, for intimacy, affection, attention, and love, as well as our simple, animal longings.

Still, like aromas from a fine kitchen, porn stimulates us without nourishing us. And by giving it too much attention we may be training ourselves to scorn good nutrition. The WSJ article suggests giving up the stimulation as a means of getting over it. I think this is incomplete without a redirection of the attention to what does in fact nourish us. Prayer and worship that refocus our conscious minds on what really merits our attention can prepare us to receive - and to give - good nutrition. That is, by shifting some of our attention from cherishing need-love to cherishing gift-love - from the love that uses others to the love that seeks their flourishing - we might make ourselves into the kind of great lovers our world most needs.

"Repetitive viewing of pornography resets neural pathways, creating the need for a type and level of stimulation not satiable in real life. The user is thrilled, then doomed."Thankfully, "doomed" may be an overstatement. As William James and so many others remind us, our habits make us who we are, so we may be able to form new habits to supplant or redirect old ones. I'm no psychologist, but it seems obvious to me that what we hold in front of our consciousness will synechistically affect everything else we think about and do. So it is no surprise that the author of this WSJ article reports that viewing porn may lead to viewing women as things rather than as people.

To put it differently, everyone worships something, and what we worship changes us. This is one of the good reasons to engage in prayer and worship that are intentional. (On a related note, it's a good reason to forgive, too: forgiveness keeps us from internalizing the pain others have caused us, where it can fester and devour us from within.)

(If you read my writing with any regularity you will recognize these as themes I frequently return to. If you're interested, I've written more here and here.)

One of the problems of philosophy of religion has been to try to identify that which certainly deserves our worship. This quest for certainty has often (in my view) distracted us from the more important work of liturgy, wherein we acknowledge our limitations, including our uncertainty. A good liturgy involves worshiping what we believe to be worth worshiping, while acknowledging our own limitations. After all, if worship doesn't include humility on the part of the worshiper, it is probably self-worship.

Another way of putting this is in terms of love. Charles Peirce wrote about this more than a century ago. There are many forms of worship, many kinds of prayer. Without intending to demean the prayer and worship of others, Peirce nevertheless offers what seems to him to be worth our attention: agape love, the love that seeks to nurture others:

"Man's highest developments are social; and religion, though it begins in a seminal individual inspiration, only comes to full flower in a great church coextensive with a civilization. This is true of every religion, but supereminently so of the religion of love. Its ideal is that the whole world shall be united in the bond of a common love of God accomplished by each man's loving his neighbour. Without a church, the religion of love can have but a rudimentary existence; and a narrow, little exclusive church is almost worse than none. A great catholic church is wanted." (Peirce, Collected Papers, 6.442-443)Notice that Peirce uses a small "c" in "catholic." He wasn't trying to proselytize for one sect; quite the opposite. He was trying to proclaim the importance of a church - that is, of a community that shares a commitment to communal worship - of nurturing love.

I am not trying to moralize about pornography. In fact, I see some good in pornography, just as I recognize goodness in the aromas coming from a kitchen where good cooking happens. Pornography probably speaks to some of our most basic desires and needs, for intimacy, affection, attention, and love, as well as our simple, animal longings.

Still, like aromas from a fine kitchen, porn stimulates us without nourishing us. And by giving it too much attention we may be training ourselves to scorn good nutrition. The WSJ article suggests giving up the stimulation as a means of getting over it. I think this is incomplete without a redirection of the attention to what does in fact nourish us. Prayer and worship that refocus our conscious minds on what really merits our attention can prepare us to receive - and to give - good nutrition. That is, by shifting some of our attention from cherishing need-love to cherishing gift-love - from the love that uses others to the love that seeks their flourishing - we might make ourselves into the kind of great lovers our world most needs.

∞

My Two-bit Prayers

Today I sent a a picture of a quarter to my daughter's mobile phone.

Since she went off to college two years ago, I have saved for her every twenty-five cent piece that I've received in change.

With each one, I remember my daughter in prayer. The photo was a reminder: I am praying for you; I love you. Whenever I see her, I give her the pile of quarters I've accumulated, so that she can use them to pay for laundry.

My prayers for her are simple, just a quick remembrance of my golden, distant girl. Keep her in your hand, Lord. Help her to do good work today. Bless her studies. Bless her life. Bless her. Bless.

A nun in Greece once told me that God does not need long prayers. God, she said, only wants from us what we are willing and able to give.

A nun in Greece once told me that God does not need long prayers. God, she said, only wants from us what we are willing and able to give.

Praying prompted by coins is probably foolish, and silly. But it is what I have to offer, a simple trick I play, a daily reminder of love.

Prayer comes hard to me, harder than I would like to admit. I can't see this God to whom I wish to speak, so speech seems strange.

Just as I cannot see this girl--this woman--for whom I am praying. I can only hope that my unseen daughter is seen by my unseen God.

And so I hold my little coin and think of them both, committing this small amount of time, this small change, to each of them.

And I hope that my small offering might be made great, by slow accumulation, or by being magnified by the one who made us all.

Since she went off to college two years ago, I have saved for her every twenty-five cent piece that I've received in change.

With each one, I remember my daughter in prayer. The photo was a reminder: I am praying for you; I love you. Whenever I see her, I give her the pile of quarters I've accumulated, so that she can use them to pay for laundry.

My prayers for her are simple, just a quick remembrance of my golden, distant girl. Keep her in your hand, Lord. Help her to do good work today. Bless her studies. Bless her life. Bless her. Bless.

A nun in Greece once told me that God does not need long prayers. God, she said, only wants from us what we are willing and able to give.

A nun in Greece once told me that God does not need long prayers. God, she said, only wants from us what we are willing and able to give.Praying prompted by coins is probably foolish, and silly. But it is what I have to offer, a simple trick I play, a daily reminder of love.

Prayer comes hard to me, harder than I would like to admit. I can't see this God to whom I wish to speak, so speech seems strange.

Just as I cannot see this girl--this woman--for whom I am praying. I can only hope that my unseen daughter is seen by my unseen God.

And so I hold my little coin and think of them both, committing this small amount of time, this small change, to each of them.

And I hope that my small offering might be made great, by slow accumulation, or by being magnified by the one who made us all.

∞

Prayer and Forgiveness

Years ago I was wronged by someone I worked with. The details don't matter, because as Viktor Frankl says, pain is like a gas, expanding to fill the available space. Even if it was a small offense, it swelled until it filled me.

I told a friend about it, who listened patiently to my story. When I was done, he said, sympathetically, "You need to pray for him and ask God to bless him."

What I had hoped to hear was something more like "Wow, what a waste of skin that guy is. Your anger is justified."

Now that I have the increasing clarity that comes when time separates us from painful events, I think my friend was right. His idea of God is that God wants all of us to be better than we are.

Praying for my former co-worker has allowed me to remove him from the center of my consciousness, where his image lived as a threatening villain, and to think of him as someone in need of healing and transformation. Blessing him has given me a way to articulate my desire to see him change and become a kinder person, for everyone's sake.

No doubt theology matters here. In plainer terms, how we imagine the God we pray to matters, because that will shape the way we act towards others. At the risk of declaring the obvious: what we think about God has consequences for the way we live with other people. In her book, Lit, Mary Karr talks about a friend who tells her that God doesn't have a plan for her, God has a dream for her. God wants good things for her.

That's an attractive idea of God, one who wants us to forgive others so we can be set free from their tyranny; and one who wants us to bless others so that we can begin to see ourselves as agents of positive change rather than as victims.

I told a friend about it, who listened patiently to my story. When I was done, he said, sympathetically, "You need to pray for him and ask God to bless him."

What I had hoped to hear was something more like "Wow, what a waste of skin that guy is. Your anger is justified."

Now that I have the increasing clarity that comes when time separates us from painful events, I think my friend was right. His idea of God is that God wants all of us to be better than we are.

Praying for my former co-worker has allowed me to remove him from the center of my consciousness, where his image lived as a threatening villain, and to think of him as someone in need of healing and transformation. Blessing him has given me a way to articulate my desire to see him change and become a kinder person, for everyone's sake.

No doubt theology matters here. In plainer terms, how we imagine the God we pray to matters, because that will shape the way we act towards others. At the risk of declaring the obvious: what we think about God has consequences for the way we live with other people. In her book, Lit, Mary Karr talks about a friend who tells her that God doesn't have a plan for her, God has a dream for her. God wants good things for her.

That's an attractive idea of God, one who wants us to forgive others so we can be set free from their tyranny; and one who wants us to bless others so that we can begin to see ourselves as agents of positive change rather than as victims.

∞

Charles Peirce's Version Of The "Lord's Prayer"

Charles Peirce's writings frequently touch on religious topics. As Douglas Anderson, Michael Raposa, Hermann Deuser and others (myself included) have argued this is not accidental but integral to his philosophy.

Throughout his life he wrote on prayer, usually tersely, though occasionally he wrote at length, as when he proposed some changes to the Episcopal Church's Book of Common Prayer based on his semeiotic theory.

Here is one piece from his journal, written while he was a student at Harvard in 1859. It appears to be a re-writing of the Lord's Prayer:

(This is from MS 891, “Private Thoughts,” number XLVI. Peirce's writings include his vast unpublished writings, mostly held at Harvard, with copies at IUPUI and Texas Tech)

Throughout his life he wrote on prayer, usually tersely, though occasionally he wrote at length, as when he proposed some changes to the Episcopal Church's Book of Common Prayer based on his semeiotic theory.

Here is one piece from his journal, written while he was a student at Harvard in 1859. It appears to be a re-writing of the Lord's Prayer:

"I pray thee, O Father, to help me regard my innate ideas as objectively valid. I would like to live as purely in accordance with thy laws as inert matter does with nature's. May I, at last, have no thoughts but thine, no wishes but thine, no will but thine. Grant me, O God, health, valor, and strength. Forgive the misuse, pray of thy former good gifts, as I do the ingratitude of my friends. Pity my weakness and deliver me, O Lord; deliver me and support me."

(This is from MS 891, “Private Thoughts,” number XLVI. Peirce's writings include his vast unpublished writings, mostly held at Harvard, with copies at IUPUI and Texas Tech)

∞

Reluctant Prayer

I do not like to pray, but I think prayer is important.

Of course, "prayer" can mean many different things, and I do not mean all of them. But - despite my disliking for the activity of prayer - I practice several kinds of prayer.

Petition and Intercession

I spend most of my prayer time asking for things. This probably sounds foolish on more than one level. Here's the thing: I use the language of asking because it's what comes most naturally. I'm not an expert at this. But this asking is, for me, like stretching my muscles before a run. If I stretch well, I can run further and faster, and I do more good than harm. Stretching prepares me to do more than I could have done otherwise. It expels stiffness and inertia and inaction.

Asking God to do good in the lives of others could be a cop-out, where we dump our problems on the divine and then proceed to ignore them. What I try to practice is a kind of asking where I'm not giving up on being part of the solution. Frankly, I think a lot of the big problems in the world will take more than just me, so I have no shame about asking God to do some of the heavy lifting. But it's also important that I take some time out of my day to practice being less concerned with my own worries and more concerned with others. This is not the run; it is the warmup, the stretching. The stretching does some good all on its own, but it also prepares me to do other good.

One part of this I have a hard time sorting out is whether and how to tell people I am praying for them. Some people are grateful for it, others are bothered by it. I understand both of those reactions. There are times when we feel the weight of grief less heavily when we know others care enough to devote part of their day to the contemplation of our suffering. And there are times when it seems like people tell us about their prayers so that we will think more highly of them. I have yet to figure this all out. I'll just say it now: if you tell me of your sorrows, I will do my best to remember those sorrows in my quiet time, and I will bring them, in silent contemplation, into the presence of my contemplation of the divine.

Make Me A Blessing

My main prayer each day is one I learned from actor Richard Gere. Years ago, after he became a Buddhist, he said in an interview that when he meets someone he says to himself, silently, "Let me be a blessing to this person." This has stayed with me, and it seems like a good prayer. (He might not call it a prayer, which is fine with me.) I begin my day with that prayer, in the abstract, something like this: "Let me be a blessing to everyone I encounter, to everyone affected by my life. Let me be a blessing, and not a curse. Let me not bring shame on anyone, and keep me from doing or saying what is foolish or harmful." This is not unlike the well-known prayer of St Francis, whose story I have loved since Professor Pardon Tillinghast first made me study it in college years ago.

We Become Like What We Worship

What lies behind all this is my hunch - and I admit it's just a hunch - that we come to resemble the things that matter most to us, the things that we treasure and mentally caress in our inmost parts. And I think this happens subtly and slowly, the way habits build up, or the way our bodies slowly change over time, one cell division at a time. The little things add up to the big thing; our small gestures become the great sweep of our lives.

So in prayer I'm trying to take time out of each day to at least expose myself once again to the things I think are most worth imitating: love of neighbor, love of justice, peacemaking, contentment, hospitality, generosity, gentleness, defense of the downtrodden, healing, joy, patience, self-control. So much of the rest of my day I wind up chasing after things that take up an amount of time that is disproportionate to their value.

If prayer does nothing else than force me to remember what I claim is important--even if this means exposing myself to myself as a hypocrite--then it has already done me some good. And I hope this will mean I'm less of a jerk to everyone else, too. When I'm honest with myself (and let's be honest, that's not as often as it should be) this leads me to what churches have long called confession and repentance, the acknowledgement that I'm not all I claim to be, that I'm not yet all I could be, that I have let myself and others down, and that needs to change. Perhaps this comes from my long interest in Socrates: I think it's probably healthy to make it a habit to consider one's own life.

Musement and Contemplation

There is another kind of prayer that I find quite difficult most of the time, but sometimes I fall into it, and when I do, it is always a delight. It happens sometimes when I am walking, or in the shower, or while reading something that utterly disrupts my usual patterns of thinking. It happens sometimes while I lie awake at night. Charles Peirce talks about this as "musement," a kind of disinterested contemplation of all our possible and actual experiences.

Emerson called prayer the consideration of the facts of the universe from the highest possible point of view. I'm not sure I get anything like the highest possible point of view when I pray, but contemplative prayer does feel like an attempt to at least consider what such a point of view would be like.