religion

On The Religious Architecture of Water

One of my recent articles on Medium. Here's a sample:

If you want to know what someone believes, don’t ask them what they believe. Ask them where they spend their time, energy, and money.

Because the things that we genuinely believe are things we act on.

And soon the landscape around us becomes the outward form of our inward beliefs.

On Religion And Robots

The Ethics of Automation: Poetry and Robot Priests

In terms of ethics and law: who has access to the information confessed, and what is the legal status of that confession? Is there anything like the privilege of confidentiality enjoyed by clergy who hear private confessions from their parishioners?

“The making of things is in my heart from my own making by thee; and the child of little understanding that makes a play of the deeds of his father may do so without thought of mockery, but because he is the son of his father.”

Might it be possible for us also to make sentient life in imitation of God "without thought of mockery," and, if so, might it be that those lives we make could write poems and become priests? As anyone who has read Tolkien's myth knows, this raises a new set of ethical questions that now have to be resolved.--J.R.R. Tolkien, Silmarillion, p 43

*****

Update, 22 May 2018: Irina Raicu just published a very thoughtful reply to this, entitled "Parenting, Politeness, Poets, and Priests" at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University. Her article is very much worth the time it will take you to read it. You may find it here.

Charles Peirce on Transcendentalism, and the Common Good

"The devotion to fair learning is not of this rabid kind, but it is more selfish. Antiquity has not accumulated its treasures for me; God has not made nature for me: if I wish to belong to the community of wise men, my time is not my own; my mind is not my own; in this age division of labor is indispensable; one man must study one thing; develope one part of his intellect and, if necessary, let the rest go, for the good of humanity. Emerson, and perhaps Everett [1], pretend to go on a different principle; but really, each has his peculiar mission. Emerson is the man-child and he does men great service by just opening himself to them. "Seraphic [2] vision!" said Carlyle. Everett possesses "action, utterance, and the power of speech to stir men's blood." Both these men do good esthetically. Everett is a gem-cutter, Emerson is a gem." (MS 1633)

|

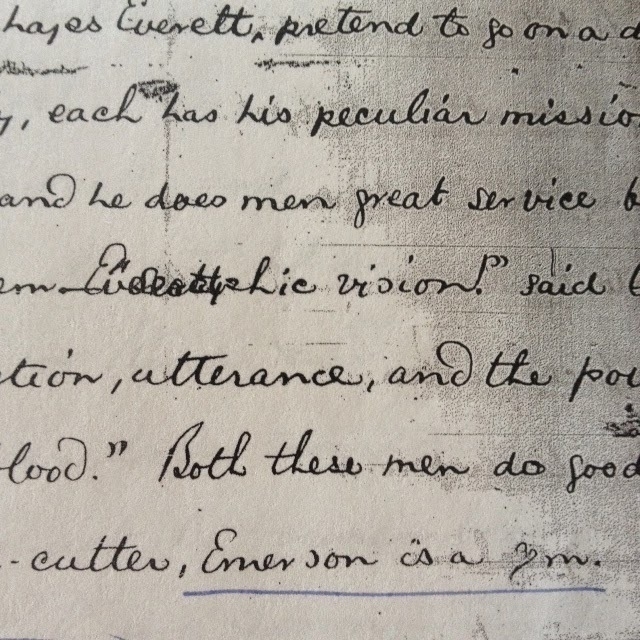

| A section of MS 1633, dated 1859 |

It's a short paragraph, but it offers considerable insight into the development of Peirce's thought, and it is full of suggestion for our own time.

His claim that a scholar must devote herself to one area only must be taken in the context of Peirce's own studies. Peirce was himself a polymath who wrote on logic, metaphysics, physics, geometry, ancient philology, semiotics, mathematics, and chemistry, among other disciplines.

What he says about learning here is relevant for the ancient tradition of publishing the results of inquiry, and for the contemporary practice of patenting all discoveries. Nature is not a gift from God to the individual researcher. Peirce's invocation of God here calls to mind what he says elsewhere about both God and research. (For more on how Peirce regarded the relationship between God and science, see my chapter in Torkild Thellefsen's collection of essays on Peirce, Peirce in His Own Words.) The idea of God provides an ideal for the researcher, a reason to expect natural research to be productive of knowledge and a reason to believe in the possible unity of knowledge.

(This helps us to understand Peirce's peculiar interest in religion, by the way: he thought religion both indispensable and unavoidable, claiming that even most atheists believe in God, though most of them are unaware of their own belief, because they have explicitly rejected a particular kind of theism while maintaining a steadfast belief in some of the consequences of theism. At the same time, Peirce was opposed to all infallible claims, to the exclusionary nature of creeds, and to what he considered to be the illogic of seminary-training.)

Peirce grew up, as he puts it, "in the neighborhood of Cambridge," i.e. near the home of American Transcendentalism. He says of his family that "one of my earliest recollections is hearing Emerson [giving] his address on 'Nature'.... So we were within hearing of the Transcendentalists, though not among them. I remember when I was a child going upon an hour's railway journey with Margaret Fuller, who had with her a book called the Imp [3] in the Bottle." (MS 1606) His critiques of Transcendentalism have to be read in this context: he was raised among them, with Emerson in his childhood living room and with Emerson's writings being discussed in his school.

Emerson's insight is that nature does speak to those who have ears to hear. His error is in mistaking the relationship of one person to another. Emerson's genius is in perceiving the Over-soul, and his error is in then presupposing the radical individuality of the genius. Peirce does not doubt that there are geniuses. As a chemist, Peirce knew the importance of research and he knew the real possibility of achieving previously unknown insight. Peirce believed, however, that the insight of the genius, or of any serious researcher for that matter, belongs to the whole community of inquiry.

Peirce, who made his living on research, believed that the researcher deserved to earn her living from her work, and he was sometimes frustrated by the chemical companies who took his ideas and patented them, then refused to pay him for them. His ideal - one that is admittedly very difficult to realize - was that all research would be made freely available to the whole community of inquiry. So while the researcher is worth her wages, no one deserves the privilege of hoarding knowledge for private gain. We are all in this together.

******

[1] I'm not sure which Everett Peirce alludes to, but possibly to Edward Everett, who was Emerson's teacher; or Alexander H. Everett, with whom Emerson corresponded.

[2] The word on Peirce's manuscript is difficult to read. I have transcribed this from a photocopy of one of Peirce's original handwritten pages. The word might be "ecstatic" but I don't think it is. See the image above. [Update: Chris Paone wrote to me with the suggestion that the obscured word might be "seraphic." This is a better guess than any I've come up with so far, so until someone has a better idea, I'll take Chris to be right.]

[3] This word is also unclear, and might read "Ink." If you're curious about this, or if you've got some insight about this, write to me in the comments below; I've spent some time trying to figure out what book Fuller had with her, so far with only a small amount of success.

With each of these footnotes, I welcome your feedback and corrections in the footnotes below. Peirce wrote that the work of the researcher is never a solitary affair, but always the work of a community of inquiry, after all.

Melville on Religion

“As Queequeg’s Ramadan, or Fasting and Humiliation, was to continue all day, I did not choose to disturb him till towards night-fall; for I cherish the greatest respect towards everybody’s religious obligations, no matter how comical, and could not find it in my heart to undervalue even a congregation of ants worshipping a toad-stool; or those other creatures in certain parts of our earth, who with a degree of footmanism quite unprecedented in other planets, bow down before the torso of a deceased landed proprietor merely on account of the inordinate possessions yet owned and rented in his name.”

Herman Melville, Moby Dick. (New York: Signet, 1980) 94, ch 17, “The Ramadan.”

Against Grading

We are sick with love of enumeration. We've discovered that counting things over time is a powerful way to predict what will happen next. And now we are mantic-obsessives, (that's not a typo) that is, people obsessed with prediction, with foresight that will rule the uncertainty of our lives.

Look: that's not such a bad thing, in a way. What I'm describing is the root and trunk of science: quantification and statistical analysis is the beating heart of our understanding of scientific laws, which are about predictive inference. Understanding of the laws of nature can save lives, and make water clean, and heal some deep wounds. Science is wonderful, and no liberal education should stint in its science offerings.

But if we're not careful - if we divorce science and enumeration from other ways of regarding value - that can make some pretty big holes in the world, too. (Whenever I hear someone say that religion is the cause of human suffering, I think "What about chemistry?" Both religion and chemistry can be deployed to change lives, and to change them dramatically. Or to end them suddenly.)

Likewise enumeration. The counting of things can give us great power to rule our own futures. It can also give us great power to rule the futures of others, and not always in kind ways. One real danger of learning to count things is that we find it too easy to shift from saying "It's hard to count X" to saying "X doesn't count."

Our quantifimania, for instance, has half of us (no, I didn't count, I'm speaking figuratively) believing that good teaching can be measured by test scores. Or that someone's intelligence can be reduced to a simple number. Or that a kid's giftedness, or ability to learn, or likelihood of living a creative and thoughtful life can be simply reduced to a GPA or a standardized test score.

Years ago, when I was thinking about beginning my graduate studies in Philosophy, a professor I knew suggested I prepare for my Ph.D. by attending St John's College's "Great Books" program. I looked over the reading list and realized that even if it didn't get me into a Ph.D. program, it would be worth it for its own sake.

As an undergraduate at an elite liberal arts college in the northeast, I was continually reminded that little mattered more than my grades. I was the sort of student who earned good grades with little effort, so it was natural to begin to believe that what mattered most came without struggle. As a result - I realize this now, in hindsight - I bypassed much of the opportunity my college offered me by studying only what my classes required of me.

This all changed in my first term at St John's, when I wrote a seminar paper on Aristotle. My tutor Matt Davis returned it to me without a grade on it. Instead, it was covered with marginal comments, underlining, and a paragraph of reflection and response at the end. But again, no grade. "How did I do?" I asked him. "Have a look at what I wrote," he replied. Sure enough, he told me how I did: here were the things that were strong; here were the gaps in my argument. No quantification, just explanation.

I wanted a grade because I'd been habituated to thinking of the grade as the way of judging the merit of my work. St John's decision to refuse to give grades is an intentional and hard-fought resistance to that way of thinking.

At the end of the term, each of my tutors gave me one, two, or even three pages of handwritten comments on my strengths and weaknesses as a student. But once again, no grades. Nothing to distract me from reading their comments, nothing that would allow me to measure the worth of their comments other than the comments themselves. And nothing to make me think: "Well, that's done."

As a result, I stopped thinking about grades and started thinking about ideas, and texts, and writing. I started caring more about correcting my ignorance than about concealing it from my peers and teachers. And I stopped thinking about learning as something that happens in fifteen-week segments. Learning was no longer something that begins here and ends there. Learning was now a river I step into, and in which I may swim, and bathe, and drink for as long as I am able. And if I step out, it remains there, ever flowing, for me to return to.

It was only then that I realized just how bored I had been in school. I had been bored since my childhood, because I had to show up, had to perform tasks, in order to get these lofty numbers that weighed so heavily and meant so little to me personally.

I've known many students who are bright but who don't do well on standardized tests. I've known many others who don't do well on any test at all, and I've no doubt that much of it has to do with anxiety over the way their work will be reduced to a number, one they feel is so disconnected from what they know. As a teacher I feel I'm constantly fighting to get my students to stop worrying about their grades, even while I'm required to assign grades to their work. Grades are, in my opinion, one of the worst things to happen to education. This is not to say I'm against evaluation or helpful feedback. I'm all for them, in fact. Which is why I'm so opposed to the damnable, lazy practice of reducing that evaluation to what can be easily counted.

The ancients tell us that King David sinned against God by counting his fighting men. (Here, too.) I think the sin was not the counting, but the way his counting became a basis for policy, and so for value. When we weigh our forces before going to war, the question shifts from "Is this a war worth fighting?" to "Can I win?" Both of those are important questions, but God save us from ever making the latter so important that we think of the former as a question that doesn't count. That kind of thinking turns people into instruments of war rather than free individuals; people become pawns, tools of policy, and they become as expendable as they are enumerable. When we dare to quantify our gains and losses in terms of numbers of human lives expended, we have already lost something important that may be very hard to regain.

And God save us, likewise, from thinking of our lives as things to be measured, and measured against others' lives. God save us from thinking of meaningful work as something to be done against a time clock, from thinking of wealth as something to be measured in numbers rather than in a richness of life. And God save us teachers and citizens from thinking that the worth of a woman or a man can easily be measured by the grades they have earned, or that the predictions we may make on the basis of those grades should have the power of prophecy.

Wettstein on Narrative Theology

“We often speak of the biblical narrative, and narrative is another aspect of the Bible’s literary character. The Bible’s characteristic mode of ‘theology’ is story telling, the stories overlaid with poetic language. Never does one find the sort of conceptually refined doctrinal propositions characteristic of a doctrinal approach. When the divine protagonist comes into view, we are not told much about his properties. Think about the divine perfections, the highly abstract omni-properties (omnipotence, omniscience, and the like), so dominant in medieval and post-medieval theology. One has to work very hard—too hard—to find even hints of these in the Biblical text. Instead of properties, perfection and the like the Bible speaks of God’s roles—father, king, friend, lover, judge, creator, and the like. Roles, as opposed to properties; this should give one pause.” (108)

I will confess that this is a difficult review to write; it's rare that I find a book that I'd rather quote at great length rather than summarize. His writing is lucid, combining analytic rigor and pragmatic vision with Talmudic wisdom. It is delicious in its suggestiveness. It's the sort of book I expect will tinge everything I write for a long time.“Biblical theology is poetically infused, not propositionally articulated.” (110)

"Come, Let Us Reason Together": Thinking About God

Using God As A Weapon?

Gandhi once wrote that “the Satyagrahi’s only weapon is God.” (A Satyagrahi is one who practices Satyagraha, Gandhi’s peaceful and powerful version of civil disobedience.)

Some of religion’s most vocal (I do not say best) contemporary critics argue that religion is either irrelevant or dangerous. It’s irrelevant, they say, because it is just an evolutionary holdover that we no longer need. It’s dangerous, they say, because it allows people to use God as a weapon.

Gandhi and many others remind us that there are two ways of using God as a weapon. If we use God to justify using other weapons to kill or oppress people, we turn God into a tool or an idol. At that point, religious people would do well to ask just what it is they’re fighting for, since it can no longer be piety.

Gandhi illustrates the other way, in which God is that which can never be taken away from us, and that which is ultimately worth living and dying for. In this way, God is not a “weapon” we wield to harm people, but one that serves to fight against injustice.

Tyrants set themselves up as gods on earth; belief in a God above the tyrant can deflate the tyrant’s power and give the Satyagrahi the necessary soul-force to “do justice, love mercy, and walk humbly with her God.” Against such things, it seems to me, only would-be tyrants and their servants will argue.