salmonids

∞

Bristol Bay and Pebble Mine: Mutual Flourishing or Midas' Touch

My latest article on salmon and mining was just published in Ethics, Policy, & Environment. A proposed gold mine in Alaska offers a lot of financial wealth, but it also poses significant risk of environmental loss to the salmon population downstream, and to everything that depends on the salmon for food.

In this brief commentary I argue that we should prefer long-term mutual flourishing over the prospect of short-term financial gain for a few. The myth of King Midas offers an illustration of what is at risk: the gleam of gold can blind us to the importance of being good stewards of nature, and of being good neighbors and good ancestors:

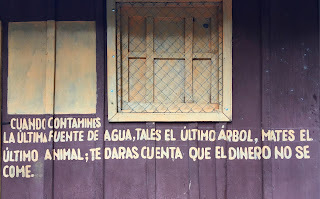

It reads "When you pollute the last source of water, cut down the last tree, and kill the last animal, you'll realize that you can't eat money."

It would be good to learn that lesson before it's too late for the salmon - and for everything that depends upon them.

You can read my article here.

In this brief commentary I argue that we should prefer long-term mutual flourishing over the prospect of short-term financial gain for a few. The myth of King Midas offers an illustration of what is at risk: the gleam of gold can blind us to the importance of being good stewards of nature, and of being good neighbors and good ancestors:

"Not all mining is bad, but to choose a mine that offers gold in exchange for life and mutual flourishing is to display a clear symptom of Midas’ malady. In the ancient myth, King Midas wished for the power to turn all he touched into gold. Half a trillion dollars in ore under the tundra might make us forget what Midas suffered when his wish was granted: he gained great wealth at great cost. When he reached out for food, it turned to inedible gold in his hand. In the case of the Pebble Mine, the risk is not to the PLP, but to the people who are sustained by a four-thousand-year-old tradition of salmon harvesting, and to all the other birds, animals, and plants that depend upon the salmon."I'm reminded of a hand-painted sign I recently came across at a ranger station in El Zotz in Guatemala's Maya Biosphere Reserve.

It reads "When you pollute the last source of water, cut down the last tree, and kill the last animal, you'll realize that you can't eat money."

It would be good to learn that lesson before it's too late for the salmon - and for everything that depends upon them.

You can read my article here.

∞

Butterflies In My Stomach

This

week I’ve been helping a student with a lepidoptera project. The project is hers, and she's not in one of my classes, though she did take the Tropical Ecology class I teach in Central America this year.

Here is the danger of becoming a professor of Environmental Humanities: people begin to assume that you care about nature, and that you are willing to share what you know.

Both of these things are true, by the way. (Many of my photos of wildlife and nature are here, on my Instagram account. I do care, and I am delighted to share the little I know.)

Over the years, I have come to love insects. This has come about partly through my years studying trout, char, and salmon, and of the places they live. I've spent a good portion of the last decade walking Appalachian waterways from Maine to Georgia. Over that same time, I've walked hundreds of miles through the remaining forests of northern Guatemala and Nicaragua. As both a researcher and teacher I've walked through the mountains of the American West; and I've made similar excursions to the foothills of the Brooks Range, the Kenai Peninsula, and Lake Clark National Park in Alaska.

The fish that I love depend upon the insects, so, like so many people who gaze at salmonids, I have come to know many riparian insects.

Once you study the insects along the streams, you start to notice the other plants and animals that depend upon them, too. In Kentucky I have come upon a steaming pile of bear scat that was full of half-digested cicadas. I've started to notice the wings of insects, left behind by the birds that only eat the fleshy bodies of the bugs they catch.

From there, it's not a big leap to realize that if the fish and the birds and the plants need the insects, then so do I. Butterflies and other insects feed the larger animals my species eats, and they pollinate the plants that feed us. All of us have the actions of butterflies in our stomachs. Can you see the lepidoptera in this next photo? There are quite a few of them, resting on the bark of this tree in Petén.

Little six-legged creatures feed us all. The small things matter.

And so do my students, even if they're not currently enrolled in one of my classes.

So in the past week I’ve gathered a few hundred of my best butterfly photos to share with my student. This photo is one of the worst in photo quality, but it’s a great image nevertheless:

I took this nine years ago in the mountains in Kentucky while working on my book on brook trout. Three distinct species of butterflies are gathered here, sipping minerals from the ground. My coauthor Matthew Dickerson and I came upon this arboreal banquet by chance.

I wish I'd had a better camera with me. For now, the blurry image is enough to bring to mind that memory of hundreds of lepidoptera sipping and supping together on the forest floor, filling their bellies with the bare earth before flying off to pollinate flowers that, through a complex net of relationships, would someday fill my belly too.

|

| Kentucky roadside butterfly banquet. Can you see the little one? |

Here is the danger of becoming a professor of Environmental Humanities: people begin to assume that you care about nature, and that you are willing to share what you know.

Both of these things are true, by the way. (Many of my photos of wildlife and nature are here, on my Instagram account. I do care, and I am delighted to share the little I know.)

*****

Over the years, I have come to love insects. This has come about partly through my years studying trout, char, and salmon, and of the places they live. I've spent a good portion of the last decade walking Appalachian waterways from Maine to Georgia. Over that same time, I've walked hundreds of miles through the remaining forests of northern Guatemala and Nicaragua. As both a researcher and teacher I've walked through the mountains of the American West; and I've made similar excursions to the foothills of the Brooks Range, the Kenai Peninsula, and Lake Clark National Park in Alaska.

The fish that I love depend upon the insects, so, like so many people who gaze at salmonids, I have come to know many riparian insects.

Once you study the insects along the streams, you start to notice the other plants and animals that depend upon them, too. In Kentucky I have come upon a steaming pile of bear scat that was full of half-digested cicadas. I've started to notice the wings of insects, left behind by the birds that only eat the fleshy bodies of the bugs they catch.

|

| Butterfly wing, left behind by birds. Guatemala. |

From there, it's not a big leap to realize that if the fish and the birds and the plants need the insects, then so do I. Butterflies and other insects feed the larger animals my species eats, and they pollinate the plants that feed us. All of us have the actions of butterflies in our stomachs. Can you see the lepidoptera in this next photo? There are quite a few of them, resting on the bark of this tree in Petén.

|

| Gray cracker butterflies, Petén, Guatemala. |

Little six-legged creatures feed us all. The small things matter.

And so do my students, even if they're not currently enrolled in one of my classes.

So in the past week I’ve gathered a few hundred of my best butterfly photos to share with my student. This photo is one of the worst in photo quality, but it’s a great image nevertheless:

|

| Butterflies on the ground in Kentucky, 2008. |

I took this nine years ago in the mountains in Kentucky while working on my book on brook trout. Three distinct species of butterflies are gathered here, sipping minerals from the ground. My coauthor Matthew Dickerson and I came upon this arboreal banquet by chance.

I wish I'd had a better camera with me. For now, the blurry image is enough to bring to mind that memory of hundreds of lepidoptera sipping and supping together on the forest floor, filling their bellies with the bare earth before flying off to pollinate flowers that, through a complex net of relationships, would someday fill my belly too.

∞

A Pretty Good Year

Last year was a pretty good year. Or at least, what I remember of it was pretty good.

As my regular readers know, I'm a professor of philosophy and classics, and I teach a wide range of classes. (You can click on the "Teaching" link above to see a sampling of the courses I teach.)

Often people assume that means I wear tweed and a bowtie and that I spend my time in classrooms talking about old books. All that is true, but it's only a part of what I do.

In fact, most of my favorite classrooms are outdoors, where I'm likely to be found wearing jeans and hiking boots, a parka, or a wetsuit and snorkel.

Over the last dozen years or so my teaching and research have tended towards the environmental humanities. Think of this as the merging of the humanities side of the liberal arts with a close observation of the natural world. I consider my work to be a continuation of the work that Thales and Aristotle did when they paid close attention to animals on the ground and to the skies above, and of the work of Peirce, Thoreau, and Bugbee, all of whom let a rising trout or a solar eclipse provoke philosophical reflection.

While I don't work in an indoor laboratory, I think that education is not about the imparting of information or the filling of an empty vessel with ideas. Education is the kindling of a fire, as Plutarch wrote. And that fire is kindled by the kinds of experiences that we get in labs, art studios, shared meals, liturgies, study travel, and seminars. Lecture halls are a fine place to discuss environmental policy, to be sure. But so is a prairie, especially when you're waiting for water to boil on your camp stove, and watching the sun's beams break over the horizon and melt a light frost on your tent.

When I'm at home, I like to take my classes outside to sit under trees on campus. In the fall, I try to bring my Ancient Philosophy students camping in the Badlands of South Dakota where we can view the stars far from urban glow. Most Januaries, my students and I are in the subtropical forests of Guatemala and on a barrier island in Belize, studying ecology and culture. I rarely take a spring break, since I usually take that week to teach a course in Greece. Last summer I started teaching a class on trout and salmon in Alaska.

Those are all beautiful, memorable places, but I don't visit them as a tourist. I go to these places because I want my students to understand what is at stake when we talk about environmental regulations and practices. I want them to meet displaced people whose permafrost islands are melting or whose forests are being burned down for meager cropland. I want them to see the disappearing mangroves so that they can consider the full cost of seafood. When they stay in homes in Guatemala, my students will meet people who can never again be a mere abstraction; after we return, my students will know that the people struggling to cross borders are not nameless, faceless strangers, but people who are looking for ways to feed those they love.

A little less than a year ago I was finishing up a year that had brought me to all these places. I taught in the South Dakota Badlands, in Central America, in Greece, and in Alaska. Along the way, I had begun studying environmental law at Vermont Law School as a way of enhancing my teaching and my research. It was a good year, and as August was winding down, my desk was covered with field notebooks full of observations from Alaska and Guatemala, ready to be written up. My field notes are usually accompanied by thousands of photographs, and hundreds of sketches. I began the fall semester last year ready to teach, and ready to write.

And then I wound up in the hospital with some serious injuries. Those injuries put a sudden stop to all my teaching last fall, and for a long time I lost most of my ability to write. (I'll try to write more about the injuries and my subsequent disabilities later; it's not an easy thing to write about yet.)

Now, as this summer hastens towards the beginning of another school year, I am able to look back on last year with a sense of good fortune - albeit mixed with one very bad day and its long-term consequences. Physically, I'm regaining my flexibility and strength, a little at a time. I'm not where I was a year ago, and I may never be there again, but I'm alive and able to walk, so I'll count that in the "win" column of my life's scorecard. Intellectually, most people seem to think I'm doing fine, so I'll also count that as a win. Although it left me exhausted each day, I was able to teach again this spring, and I plan to be back in my classrooms (Deo volente!) this fall.

But here are these field notebooks, and hundreds of unedited pages on my hard drive. It was my habit to write daily. Over the last year, recovering from a brain injury has made it hard to write more than a few sentences at a time.

This morning I was looking at some of my pictures from my research in the Arctic last summer, and I was hit with a feeling of loss. Those photos and those notes should be a book by now, and perhaps several articles and book chapters, too. Instead, over the last year, as I have waited for my body and brain to heal, and as I struggled to do my teaching, I had no strength to write.

It feels funny to say that, but perhaps I am not alone in finding that a brain injury can be slow to heal and extremely tiring. I don't say that to get your sympathy. I am blessed with a very supportive community and an amazing wife who somehow has kept our life together and nursed me through my healing process. I'm fortunate. But if you've read this far, you might consider whether there are others around you who look like they're doing well physically but who might be nursing invisible wounds or who might be struggling to cope with invisible disabilities. This past year has given me a new perspective on that by making me aware of my own disabilities, most of which you won't notice if you see me at the gym or in one of my classrooms.

I might not be able to write another book yet, so for now, here's my plan: I'll write a little at a time. Thankfully, I've got my notes, sketches, and photos. I'll start with them.

If you're curious about how a professor of philosophy and classics does research and writing about nature - and how he works to recover from a serious brain injury - you might check out some of my recent publications. My book Downstream is the result of eight years of field research on the ecology of the Appalachians, with a focus on brook trout. On this blog you'll also find my recently published poem, "Sage Creek," which might give you a glimpse of my ancient philosophy class camping and stargazing in the Badlands. Or feel free to look at my photos on Instagram. Even when I can't teach in the field, I can still wander my garden with a hand lens and camera.

As my regular readers know, I'm a professor of philosophy and classics, and I teach a wide range of classes. (You can click on the "Teaching" link above to see a sampling of the courses I teach.)

Often people assume that means I wear tweed and a bowtie and that I spend my time in classrooms talking about old books. All that is true, but it's only a part of what I do.

In fact, most of my favorite classrooms are outdoors, where I'm likely to be found wearing jeans and hiking boots, a parka, or a wetsuit and snorkel.

Over the last dozen years or so my teaching and research have tended towards the environmental humanities. Think of this as the merging of the humanities side of the liberal arts with a close observation of the natural world. I consider my work to be a continuation of the work that Thales and Aristotle did when they paid close attention to animals on the ground and to the skies above, and of the work of Peirce, Thoreau, and Bugbee, all of whom let a rising trout or a solar eclipse provoke philosophical reflection.

While I don't work in an indoor laboratory, I think that education is not about the imparting of information or the filling of an empty vessel with ideas. Education is the kindling of a fire, as Plutarch wrote. And that fire is kindled by the kinds of experiences that we get in labs, art studios, shared meals, liturgies, study travel, and seminars. Lecture halls are a fine place to discuss environmental policy, to be sure. But so is a prairie, especially when you're waiting for water to boil on your camp stove, and watching the sun's beams break over the horizon and melt a light frost on your tent.

When I'm at home, I like to take my classes outside to sit under trees on campus. In the fall, I try to bring my Ancient Philosophy students camping in the Badlands of South Dakota where we can view the stars far from urban glow. Most Januaries, my students and I are in the subtropical forests of Guatemala and on a barrier island in Belize, studying ecology and culture. I rarely take a spring break, since I usually take that week to teach a course in Greece. Last summer I started teaching a class on trout and salmon in Alaska.

Those are all beautiful, memorable places, but I don't visit them as a tourist. I go to these places because I want my students to understand what is at stake when we talk about environmental regulations and practices. I want them to meet displaced people whose permafrost islands are melting or whose forests are being burned down for meager cropland. I want them to see the disappearing mangroves so that they can consider the full cost of seafood. When they stay in homes in Guatemala, my students will meet people who can never again be a mere abstraction; after we return, my students will know that the people struggling to cross borders are not nameless, faceless strangers, but people who are looking for ways to feed those they love.

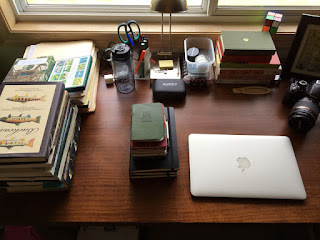

A little less than a year ago I was finishing up a year that had brought me to all these places. I taught in the South Dakota Badlands, in Central America, in Greece, and in Alaska. Along the way, I had begun studying environmental law at Vermont Law School as a way of enhancing my teaching and my research. It was a good year, and as August was winding down, my desk was covered with field notebooks full of observations from Alaska and Guatemala, ready to be written up. My field notes are usually accompanied by thousands of photographs, and hundreds of sketches. I began the fall semester last year ready to teach, and ready to write.

|

| Field notes. A picture of some of the work I do when I'm inside, and not teaching; or, if you like, a picture of my desk as I recover from my injuries. I have a lot of catching up to do. |

And then I wound up in the hospital with some serious injuries. Those injuries put a sudden stop to all my teaching last fall, and for a long time I lost most of my ability to write. (I'll try to write more about the injuries and my subsequent disabilities later; it's not an easy thing to write about yet.)

Now, as this summer hastens towards the beginning of another school year, I am able to look back on last year with a sense of good fortune - albeit mixed with one very bad day and its long-term consequences. Physically, I'm regaining my flexibility and strength, a little at a time. I'm not where I was a year ago, and I may never be there again, but I'm alive and able to walk, so I'll count that in the "win" column of my life's scorecard. Intellectually, most people seem to think I'm doing fine, so I'll also count that as a win. Although it left me exhausted each day, I was able to teach again this spring, and I plan to be back in my classrooms (Deo volente!) this fall.

But here are these field notebooks, and hundreds of unedited pages on my hard drive. It was my habit to write daily. Over the last year, recovering from a brain injury has made it hard to write more than a few sentences at a time.

This morning I was looking at some of my pictures from my research in the Arctic last summer, and I was hit with a feeling of loss. Those photos and those notes should be a book by now, and perhaps several articles and book chapters, too. Instead, over the last year, as I have waited for my body and brain to heal, and as I struggled to do my teaching, I had no strength to write.

It feels funny to say that, but perhaps I am not alone in finding that a brain injury can be slow to heal and extremely tiring. I don't say that to get your sympathy. I am blessed with a very supportive community and an amazing wife who somehow has kept our life together and nursed me through my healing process. I'm fortunate. But if you've read this far, you might consider whether there are others around you who look like they're doing well physically but who might be nursing invisible wounds or who might be struggling to cope with invisible disabilities. This past year has given me a new perspective on that by making me aware of my own disabilities, most of which you won't notice if you see me at the gym or in one of my classrooms.

I might not be able to write another book yet, so for now, here's my plan: I'll write a little at a time. Thankfully, I've got my notes, sketches, and photos. I'll start with them.

If you're curious about how a professor of philosophy and classics does research and writing about nature - and how he works to recover from a serious brain injury - you might check out some of my recent publications. My book Downstream is the result of eight years of field research on the ecology of the Appalachians, with a focus on brook trout. On this blog you'll also find my recently published poem, "Sage Creek," which might give you a glimpse of my ancient philosophy class camping and stargazing in the Badlands. Or feel free to look at my photos on Instagram. Even when I can't teach in the field, I can still wander my garden with a hand lens and camera.