Science

- The trust they've placed in their community. Think about it: if your parents or your pastor or someone else you trusted taught you that there's an irreconcilable conflict between science and faith, you might distrust anyone who said otherwise. It might help such students to go back to that community and ask the question I posed above. This may take time, because there's a lot at stake here.

- An even bigger concern is the question of human dignity. I think that's what's behind the old complaint that "I'm not descended from monkeys." If the student is simply concerned about being descended from unwashed furry critters, they should probably look more closely at their family trees. Monkeys are often nicer than our actual relatives.

- But there's another concern here that's actually quite positive, because it means that they care about ethics, and they're trying to preserve that in the face of a perceived threat. Some students correctly intuit that what's at stake in evolution is not merely a theory of descent but a whole theory of knowledge, and of metaphysics. Natural sciences rest upon an assumption of methodological naturalism. That is, they assume that it is possible to explain natural phenomena by appeal to nature and nothing else. So far, so good. But sometimes we then make a little leap to saying that therefore whatever naturalism cannot explain is unknowable or nonexistent. This is not just naturalism but a kind of reductionistic naturalism, and it's tricky territory, because it might imply that there is no real basis for ethics, or for valuing others' lives. I'm not saying we're not free to value others' lives; I'm just saying that some of these students want to believe that there are good reasons to expect everyone to value everyone, not merely a world of subjective interests. And many of them are reasonably suspicious that reductionistic naturalism cannot itself be supported by science; after all, how could natural science prove that what it can't see isn't there? Such claims sound a bit like the misdirection of Wizard of Oz: "Pay no attention to the man behind the curtain!" We'd be better off avoiding such claims, both because we cannot prove them and because they do a disservice to science.

∞

The Sentiment That Invites Us To Pray - Peirce on Prayer and Inquiry

"One of Peirce’s ongoing aims was

to reconcile religious life with the practice and spirit of science.

Given the great differences between religion and science—in both

practical and theoretical terms—this may have seemed like a fool’s

errand in his time, and even more so in our time. The spirit of science

is one of progress and fallibility, an open community whose only heresy

is an unwillingness to seek the truth, while the spirit of religion

includes a tendency towards conservative closure of inquiry and of

membership. While Peirce acknowledged these distinctions, he

nevertheless maintained that religion was not necessarily

opposed to science. Certain aspects of religious practice —and

especially the act of prayer—exemplify elements of inquiry. Rather than

causing thought to contract and community to become less important, as

is often supposed, practice in prayer may be a creative act, like

poetry, that can in fact lead to greater understanding of the world and

of one’s place in it. At its best, prayer arises from an instinct or

from a sentiment, and it affords comfort, strength, and—perhaps most

importantly—insight into the nature of the world...."

Read the rest here, in the latest volume of the Journal Of Scriptural Reasoning.

Read the rest here, in the latest volume of the Journal Of Scriptural Reasoning.

∞

Is Thinking Real? Peirce On Neuro-Determinism

"Tell me, upon sufficient authority, that all cerebration depends upon

movements of neurites that strictly obey certain physical laws, and that

thus all expressions of thought, both external and internal, receive a

physical explanation, and I shall be ready to believe you. But if you go

on to say that this explodes the theory that my neighbour and myself

are governed by reason, and are thinking beings, I must frankly say that

it will not give me a high opinion of your intelligence."

Charles Sanders Peirce, "A Neglected Argument For The Reality Of God."

∞

Charles Peirce on Transcendentalism, and the Common Good

From one of Charles S. Peirce's college writings, dated 1859. At the time he was a student at Harvard College.

It's a short paragraph, but it offers considerable insight into the development of Peirce's thought, and it is full of suggestion for our own time.

His claim that a scholar must devote herself to one area only must be taken in the context of Peirce's own studies. Peirce was himself a polymath who wrote on logic, metaphysics, physics, geometry, ancient philology, semiotics, mathematics, and chemistry, among other disciplines.

What he says about learning here is relevant for the ancient tradition of publishing the results of inquiry, and for the contemporary practice of patenting all discoveries. Nature is not a gift from God to the individual researcher. Peirce's invocation of God here calls to mind what he says elsewhere about both God and research. (For more on how Peirce regarded the relationship between God and science, see my chapter in Torkild Thellefsen's collection of essays on Peirce, Peirce in His Own Words.) The idea of God provides an ideal for the researcher, a reason to expect natural research to be productive of knowledge and a reason to believe in the possible unity of knowledge.

(This helps us to understand Peirce's peculiar interest in religion, by the way: he thought religion both indispensable and unavoidable, claiming that even most atheists believe in God, though most of them are unaware of their own belief, because they have explicitly rejected a particular kind of theism while maintaining a steadfast belief in some of the consequences of theism. At the same time, Peirce was opposed to all infallible claims, to the exclusionary nature of creeds, and to what he considered to be the illogic of seminary-training.)

Peirce grew up, as he puts it, "in the neighborhood of Cambridge," i.e. near the home of American Transcendentalism. He says of his family that "one of my earliest recollections is hearing Emerson [giving] his address on 'Nature'.... So we were within hearing of the Transcendentalists, though not among them. I remember when I was a child going upon an hour's railway journey with Margaret Fuller, who had with her a book called the Imp [3] in the Bottle." (MS 1606) His critiques of Transcendentalism have to be read in this context: he was raised among them, with Emerson in his childhood living room and with Emerson's writings being discussed in his school.

Emerson's insight is that nature does speak to those who have ears to hear. His error is in mistaking the relationship of one person to another. Emerson's genius is in perceiving the Over-soul, and his error is in then presupposing the radical individuality of the genius. Peirce does not doubt that there are geniuses. As a chemist, Peirce knew the importance of research and he knew the real possibility of achieving previously unknown insight. Peirce believed, however, that the insight of the genius, or of any serious researcher for that matter, belongs to the whole community of inquiry.

Peirce, who made his living on research, believed that the researcher deserved to earn her living from her work, and he was sometimes frustrated by the chemical companies who took his ideas and patented them, then refused to pay him for them. His ideal - one that is admittedly very difficult to realize - was that all research would be made freely available to the whole community of inquiry. So while the researcher is worth her wages, no one deserves the privilege of hoarding knowledge for private gain. We are all in this together.

******

[1] I'm not sure which Everett Peirce alludes to, but possibly to Edward Everett, who was Emerson's teacher; or Alexander H. Everett, with whom Emerson corresponded.

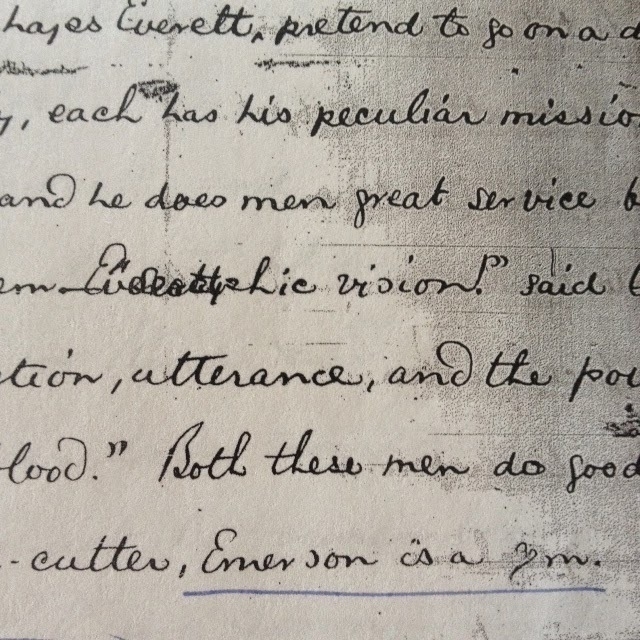

[2] The word on Peirce's manuscript is difficult to read. I have transcribed this from a photocopy of one of Peirce's original handwritten pages. The word might be "ecstatic" but I don't think it is. See the image above. [Update: Chris Paone wrote to me with the suggestion that the obscured word might be "seraphic." This is a better guess than any I've come up with so far, so until someone has a better idea, I'll take Chris to be right.]

[3] This word is also unclear, and might read "Ink." If you're curious about this, or if you've got some insight about this, write to me in the comments below; I've spent some time trying to figure out what book Fuller had with her, so far with only a small amount of success.

With each of these footnotes, I welcome your feedback and corrections in the footnotes below. Peirce wrote that the work of the researcher is never a solitary affair, but always the work of a community of inquiry, after all.

"The devotion to fair learning is not of this rabid kind, but it is more selfish. Antiquity has not accumulated its treasures for me; God has not made nature for me: if I wish to belong to the community of wise men, my time is not my own; my mind is not my own; in this age division of labor is indispensable; one man must study one thing; develope one part of his intellect and, if necessary, let the rest go, for the good of humanity. Emerson, and perhaps Everett [1], pretend to go on a different principle; but really, each has his peculiar mission. Emerson is the man-child and he does men great service by just opening himself to them. "Seraphic [2] vision!" said Carlyle. Everett possesses "action, utterance, and the power of speech to stir men's blood." Both these men do good esthetically. Everett is a gem-cutter, Emerson is a gem." (MS 1633)

|

| A section of MS 1633, dated 1859 |

It's a short paragraph, but it offers considerable insight into the development of Peirce's thought, and it is full of suggestion for our own time.

His claim that a scholar must devote herself to one area only must be taken in the context of Peirce's own studies. Peirce was himself a polymath who wrote on logic, metaphysics, physics, geometry, ancient philology, semiotics, mathematics, and chemistry, among other disciplines.

What he says about learning here is relevant for the ancient tradition of publishing the results of inquiry, and for the contemporary practice of patenting all discoveries. Nature is not a gift from God to the individual researcher. Peirce's invocation of God here calls to mind what he says elsewhere about both God and research. (For more on how Peirce regarded the relationship between God and science, see my chapter in Torkild Thellefsen's collection of essays on Peirce, Peirce in His Own Words.) The idea of God provides an ideal for the researcher, a reason to expect natural research to be productive of knowledge and a reason to believe in the possible unity of knowledge.

(This helps us to understand Peirce's peculiar interest in religion, by the way: he thought religion both indispensable and unavoidable, claiming that even most atheists believe in God, though most of them are unaware of their own belief, because they have explicitly rejected a particular kind of theism while maintaining a steadfast belief in some of the consequences of theism. At the same time, Peirce was opposed to all infallible claims, to the exclusionary nature of creeds, and to what he considered to be the illogic of seminary-training.)

Peirce grew up, as he puts it, "in the neighborhood of Cambridge," i.e. near the home of American Transcendentalism. He says of his family that "one of my earliest recollections is hearing Emerson [giving] his address on 'Nature'.... So we were within hearing of the Transcendentalists, though not among them. I remember when I was a child going upon an hour's railway journey with Margaret Fuller, who had with her a book called the Imp [3] in the Bottle." (MS 1606) His critiques of Transcendentalism have to be read in this context: he was raised among them, with Emerson in his childhood living room and with Emerson's writings being discussed in his school.

Emerson's insight is that nature does speak to those who have ears to hear. His error is in mistaking the relationship of one person to another. Emerson's genius is in perceiving the Over-soul, and his error is in then presupposing the radical individuality of the genius. Peirce does not doubt that there are geniuses. As a chemist, Peirce knew the importance of research and he knew the real possibility of achieving previously unknown insight. Peirce believed, however, that the insight of the genius, or of any serious researcher for that matter, belongs to the whole community of inquiry.

Peirce, who made his living on research, believed that the researcher deserved to earn her living from her work, and he was sometimes frustrated by the chemical companies who took his ideas and patented them, then refused to pay him for them. His ideal - one that is admittedly very difficult to realize - was that all research would be made freely available to the whole community of inquiry. So while the researcher is worth her wages, no one deserves the privilege of hoarding knowledge for private gain. We are all in this together.

******

[1] I'm not sure which Everett Peirce alludes to, but possibly to Edward Everett, who was Emerson's teacher; or Alexander H. Everett, with whom Emerson corresponded.

[2] The word on Peirce's manuscript is difficult to read. I have transcribed this from a photocopy of one of Peirce's original handwritten pages. The word might be "ecstatic" but I don't think it is. See the image above. [Update: Chris Paone wrote to me with the suggestion that the obscured word might be "seraphic." This is a better guess than any I've come up with so far, so until someone has a better idea, I'll take Chris to be right.]

[3] This word is also unclear, and might read "Ink." If you're curious about this, or if you've got some insight about this, write to me in the comments below; I've spent some time trying to figure out what book Fuller had with her, so far with only a small amount of success.

With each of these footnotes, I welcome your feedback and corrections in the footnotes below. Peirce wrote that the work of the researcher is never a solitary affair, but always the work of a community of inquiry, after all.

∞

Augustine once said that a key to his conversion was when he met St Ambrose. Augustine had regarded the Bible as full of flawed and problematic texts. As Augustine put it, "by taking them literally, I had found them to kill."(1) Ambrose taught Augustine that the texts of the Bible may have more than one sense. The scriptures might speak to him in more than one way. When he heard this, and heard it from a man who thought it important to study science and the liberal arts, Augustine found his spiritual home in Christianity.

Augustine once said that a key to his conversion was when he met St Ambrose. Augustine had regarded the Bible as full of flawed and problematic texts. As Augustine put it, "by taking them literally, I had found them to kill."(1) Ambrose taught Augustine that the texts of the Bible may have more than one sense. The scriptures might speak to him in more than one way. When he heard this, and heard it from a man who thought it important to study science and the liberal arts, Augustine found his spiritual home in Christianity.

In recent years authors like Norman Wirzba, Bill McKibben, and Scott Russell Sanders have written about the relevance of Biblical texts for thinking about ecology. To me, they have been a little like St Ambrose. I've found one passage in Sanders to be quite helpful personally as I think about the management of my little suburban fifth-acre plot.

In his A Conservationist Manifesto, Sanders writes about the story of Noah and the Ark. He remembers that Noah was given the task of saving not just himself but every other species as well. And once they were on the ark, it was his job to care for the animals and to keep them alive. Sanders talks about books, and communities, and practices that can be like small arks in our time. One such "ark" may be the little plots of land we maintain around our homes:

*****

(1) Augustine, Confessions. Henry Chadwick's translation. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998) p. 88.

(2) Scott Russell Sanders, A Conservationist Manifesto. (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2009) p. 16.

*****

All of these images were taken by David O'Hara in the fall of 2013. You may use them elsewhere but please mention where you found them and give credit where it is due. Thanks.

My Backyard Ark

Augustine once said that a key to his conversion was when he met St Ambrose. Augustine had regarded the Bible as full of flawed and problematic texts. As Augustine put it, "by taking them literally, I had found them to kill."(1) Ambrose taught Augustine that the texts of the Bible may have more than one sense. The scriptures might speak to him in more than one way. When he heard this, and heard it from a man who thought it important to study science and the liberal arts, Augustine found his spiritual home in Christianity.

Augustine once said that a key to his conversion was when he met St Ambrose. Augustine had regarded the Bible as full of flawed and problematic texts. As Augustine put it, "by taking them literally, I had found them to kill."(1) Ambrose taught Augustine that the texts of the Bible may have more than one sense. The scriptures might speak to him in more than one way. When he heard this, and heard it from a man who thought it important to study science and the liberal arts, Augustine found his spiritual home in Christianity.In recent years authors like Norman Wirzba, Bill McKibben, and Scott Russell Sanders have written about the relevance of Biblical texts for thinking about ecology. To me, they have been a little like St Ambrose. I've found one passage in Sanders to be quite helpful personally as I think about the management of my little suburban fifth-acre plot.

In his A Conservationist Manifesto, Sanders writes about the story of Noah and the Ark. He remembers that Noah was given the task of saving not just himself but every other species as well. And once they were on the ark, it was his job to care for the animals and to keep them alive. Sanders talks about books, and communities, and practices that can be like small arks in our time. One such "ark" may be the little plots of land we maintain around our homes:

"Every unsprayed garden and unkempt yard, every meadow, marsh, and woods may become a reservoir for biological possibilities, keeping alive creatures who bear in their genes millions of years; worth of evolutionary discoveries. Every such refuge may also become a reservoir for spiritual possibilities, keeping alive our connection with the land, reminding us of our origins in the green world."(2)Lately I've been surveying my yard more closely, looking to see whom I'm sharing it with, and how. I've been trying to do some phenology, like Thoreau did. I also wander my garden with lenses: a hand lens for close inspection; my phone camera and my SLR for keeping records of what lives and grows there; and I've recently set up an infrared game camera to see who passes through at night. For the curious, I've posted some photos below of what I've seen there.

*****

(1) Augustine, Confessions. Henry Chadwick's translation. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998) p. 88.

(2) Scott Russell Sanders, A Conservationist Manifesto. (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2009) p. 16.

*****

All of these images were taken by David O'Hara in the fall of 2013. You may use them elsewhere but please mention where you found them and give credit where it is due. Thanks.

∞

Against Grading

One of the best things to happen in my education was when I attended a school - a graduate school - that refused to give grades. "How is that possible?" you may ask. "What kind of fluffy, feel-good, no-good education did you get there?" To which I reply: a damn good one; one of the best. Curious? Read on:

We are sick with love of enumeration. We've discovered that counting things over time is a powerful way to predict what will happen next. And now we are mantic-obsessives, (that's not a typo) that is, people obsessed with prediction, with foresight that will rule the uncertainty of our lives.

Look: that's not such a bad thing, in a way. What I'm describing is the root and trunk of science: quantification and statistical analysis is the beating heart of our understanding of scientific laws, which are about predictive inference. Understanding of the laws of nature can save lives, and make water clean, and heal some deep wounds. Science is wonderful, and no liberal education should stint in its science offerings.

But if we're not careful - if we divorce science and enumeration from other ways of regarding value - that can make some pretty big holes in the world, too. (Whenever I hear someone say that religion is the cause of human suffering, I think "What about chemistry?" Both religion and chemistry can be deployed to change lives, and to change them dramatically. Or to end them suddenly.)

Likewise enumeration. The counting of things can give us great power to rule our own futures. It can also give us great power to rule the futures of others, and not always in kind ways. One real danger of learning to count things is that we find it too easy to shift from saying "It's hard to count X" to saying "X doesn't count."

Our quantifimania, for instance, has half of us (no, I didn't count, I'm speaking figuratively) believing that good teaching can be measured by test scores. Or that someone's intelligence can be reduced to a simple number. Or that a kid's giftedness, or ability to learn, or likelihood of living a creative and thoughtful life can be simply reduced to a GPA or a standardized test score.

Years ago, when I was thinking about beginning my graduate studies in Philosophy, a professor I knew suggested I prepare for my Ph.D. by attending St John's College's "Great Books" program. I looked over the reading list and realized that even if it didn't get me into a Ph.D. program, it would be worth it for its own sake.

As an undergraduate at an elite liberal arts college in the northeast, I was continually reminded that little mattered more than my grades. I was the sort of student who earned good grades with little effort, so it was natural to begin to believe that what mattered most came without struggle. As a result - I realize this now, in hindsight - I bypassed much of the opportunity my college offered me by studying only what my classes required of me.

This all changed in my first term at St John's, when I wrote a seminar paper on Aristotle. My tutor Matt Davis returned it to me without a grade on it. Instead, it was covered with marginal comments, underlining, and a paragraph of reflection and response at the end. But again, no grade. "How did I do?" I asked him. "Have a look at what I wrote," he replied. Sure enough, he told me how I did: here were the things that were strong; here were the gaps in my argument. No quantification, just explanation.

I wanted a grade because I'd been habituated to thinking of the grade as the way of judging the merit of my work. St John's decision to refuse to give grades is an intentional and hard-fought resistance to that way of thinking.

At the end of the term, each of my tutors gave me one, two, or even three pages of handwritten comments on my strengths and weaknesses as a student. But once again, no grades. Nothing to distract me from reading their comments, nothing that would allow me to measure the worth of their comments other than the comments themselves. And nothing to make me think: "Well, that's done."

As a result, I stopped thinking about grades and started thinking about ideas, and texts, and writing. I started caring more about correcting my ignorance than about concealing it from my peers and teachers. And I stopped thinking about learning as something that happens in fifteen-week segments. Learning was no longer something that begins here and ends there. Learning was now a river I step into, and in which I may swim, and bathe, and drink for as long as I am able. And if I step out, it remains there, ever flowing, for me to return to.

It was only then that I realized just how bored I had been in school. I had been bored since my childhood, because I had to show up, had to perform tasks, in order to get these lofty numbers that weighed so heavily and meant so little to me personally.

I've known many students who are bright but who don't do well on standardized tests. I've known many others who don't do well on any test at all, and I've no doubt that much of it has to do with anxiety over the way their work will be reduced to a number, one they feel is so disconnected from what they know. As a teacher I feel I'm constantly fighting to get my students to stop worrying about their grades, even while I'm required to assign grades to their work. Grades are, in my opinion, one of the worst things to happen to education. This is not to say I'm against evaluation or helpful feedback. I'm all for them, in fact. Which is why I'm so opposed to the damnable, lazy practice of reducing that evaluation to what can be easily counted.

The ancients tell us that King David sinned against God by counting his fighting men. (Here, too.) I think the sin was not the counting, but the way his counting became a basis for policy, and so for value. When we weigh our forces before going to war, the question shifts from "Is this a war worth fighting?" to "Can I win?" Both of those are important questions, but God save us from ever making the latter so important that we think of the former as a question that doesn't count. That kind of thinking turns people into instruments of war rather than free individuals; people become pawns, tools of policy, and they become as expendable as they are enumerable. When we dare to quantify our gains and losses in terms of numbers of human lives expended, we have already lost something important that may be very hard to regain.

And God save us, likewise, from thinking of our lives as things to be measured, and measured against others' lives. God save us from thinking of meaningful work as something to be done against a time clock, from thinking of wealth as something to be measured in numbers rather than in a richness of life. And God save us teachers and citizens from thinking that the worth of a woman or a man can easily be measured by the grades they have earned, or that the predictions we may make on the basis of those grades should have the power of prophecy.

*****

We are sick with love of enumeration. We've discovered that counting things over time is a powerful way to predict what will happen next. And now we are mantic-obsessives, (that's not a typo) that is, people obsessed with prediction, with foresight that will rule the uncertainty of our lives.

Look: that's not such a bad thing, in a way. What I'm describing is the root and trunk of science: quantification and statistical analysis is the beating heart of our understanding of scientific laws, which are about predictive inference. Understanding of the laws of nature can save lives, and make water clean, and heal some deep wounds. Science is wonderful, and no liberal education should stint in its science offerings.

But if we're not careful - if we divorce science and enumeration from other ways of regarding value - that can make some pretty big holes in the world, too. (Whenever I hear someone say that religion is the cause of human suffering, I think "What about chemistry?" Both religion and chemistry can be deployed to change lives, and to change them dramatically. Or to end them suddenly.)

Likewise enumeration. The counting of things can give us great power to rule our own futures. It can also give us great power to rule the futures of others, and not always in kind ways. One real danger of learning to count things is that we find it too easy to shift from saying "It's hard to count X" to saying "X doesn't count."

Our quantifimania, for instance, has half of us (no, I didn't count, I'm speaking figuratively) believing that good teaching can be measured by test scores. Or that someone's intelligence can be reduced to a simple number. Or that a kid's giftedness, or ability to learn, or likelihood of living a creative and thoughtful life can be simply reduced to a GPA or a standardized test score.

Years ago, when I was thinking about beginning my graduate studies in Philosophy, a professor I knew suggested I prepare for my Ph.D. by attending St John's College's "Great Books" program. I looked over the reading list and realized that even if it didn't get me into a Ph.D. program, it would be worth it for its own sake.

As an undergraduate at an elite liberal arts college in the northeast, I was continually reminded that little mattered more than my grades. I was the sort of student who earned good grades with little effort, so it was natural to begin to believe that what mattered most came without struggle. As a result - I realize this now, in hindsight - I bypassed much of the opportunity my college offered me by studying only what my classes required of me.

This all changed in my first term at St John's, when I wrote a seminar paper on Aristotle. My tutor Matt Davis returned it to me without a grade on it. Instead, it was covered with marginal comments, underlining, and a paragraph of reflection and response at the end. But again, no grade. "How did I do?" I asked him. "Have a look at what I wrote," he replied. Sure enough, he told me how I did: here were the things that were strong; here were the gaps in my argument. No quantification, just explanation.

I wanted a grade because I'd been habituated to thinking of the grade as the way of judging the merit of my work. St John's decision to refuse to give grades is an intentional and hard-fought resistance to that way of thinking.

At the end of the term, each of my tutors gave me one, two, or even three pages of handwritten comments on my strengths and weaknesses as a student. But once again, no grades. Nothing to distract me from reading their comments, nothing that would allow me to measure the worth of their comments other than the comments themselves. And nothing to make me think: "Well, that's done."

As a result, I stopped thinking about grades and started thinking about ideas, and texts, and writing. I started caring more about correcting my ignorance than about concealing it from my peers and teachers. And I stopped thinking about learning as something that happens in fifteen-week segments. Learning was no longer something that begins here and ends there. Learning was now a river I step into, and in which I may swim, and bathe, and drink for as long as I am able. And if I step out, it remains there, ever flowing, for me to return to.

It was only then that I realized just how bored I had been in school. I had been bored since my childhood, because I had to show up, had to perform tasks, in order to get these lofty numbers that weighed so heavily and meant so little to me personally.

I've known many students who are bright but who don't do well on standardized tests. I've known many others who don't do well on any test at all, and I've no doubt that much of it has to do with anxiety over the way their work will be reduced to a number, one they feel is so disconnected from what they know. As a teacher I feel I'm constantly fighting to get my students to stop worrying about their grades, even while I'm required to assign grades to their work. Grades are, in my opinion, one of the worst things to happen to education. This is not to say I'm against evaluation or helpful feedback. I'm all for them, in fact. Which is why I'm so opposed to the damnable, lazy practice of reducing that evaluation to what can be easily counted.

The ancients tell us that King David sinned against God by counting his fighting men. (Here, too.) I think the sin was not the counting, but the way his counting became a basis for policy, and so for value. When we weigh our forces before going to war, the question shifts from "Is this a war worth fighting?" to "Can I win?" Both of those are important questions, but God save us from ever making the latter so important that we think of the former as a question that doesn't count. That kind of thinking turns people into instruments of war rather than free individuals; people become pawns, tools of policy, and they become as expendable as they are enumerable. When we dare to quantify our gains and losses in terms of numbers of human lives expended, we have already lost something important that may be very hard to regain.

And God save us, likewise, from thinking of our lives as things to be measured, and measured against others' lives. God save us from thinking of meaningful work as something to be done against a time clock, from thinking of wealth as something to be measured in numbers rather than in a richness of life. And God save us teachers and citizens from thinking that the worth of a woman or a man can easily be measured by the grades they have earned, or that the predictions we may make on the basis of those grades should have the power of prophecy.

∞

A number of times in the last few years I've read statements by prominent scientists about the irrelevance of philosophy, echoing Richard Feynman's famous quip that "Philosophy of science is about as useful to scientists as ornithology is to birds."

Feynman was just talking about philosophers of science, which is just one narrow slice of the philosophic pie. More recently others, like Freeman Dyson, have made broader indictments of philosophy, or like Lawrence Krauss, of the humanities generally.

Dyson, in an article he wrote for the New York Review of Books, described today's philosophers as "a sorry bunch of dwarfs. They are thinking deep thoughts and giving scholarly lectures to academic audiences, but hardly anybody in the world outside is listening. They are historically insignificant." Yes, we have a technical vocabulary that outsiders often have trouble understanding. But that's true of every discipline. And yes, we don't seem to have anyone in our discipline who is writing the next Job or Republic right now, but that's been true almost always. No discipline consistently produces nothing but geniuses. Many of us in every discipline live our careers out bearing the gifts of the past forward to another generation so that they might benefit from them and add to them. And many of us are content to be forgotten as long as the books of wisdom entrusted to us are remembered.

In his recent book A Universe From Nothing, Krauss seems to be at pains to point out that without the sciences, the humanities are virtually useless, and that even with the sciences, the humanities are still virtually useless. His introduction pushes the humanities back at arm's length and invites them to clear out while science handles all the real heavy lifting.

What stands out for me as I read these scientists and some others writing in a similar vein is that they write like they're on the defensive and feeling embattled. My guess is that they see themselves or their disciplines as being engaged in an important fight about cultural values, science education, and research funding. The outsized reaction to Thomas Nagel's recent Mind and Cosmos - with its inflammatory subtitle, "Why The Materialist Neo-Darwinian Conception of Nature Is Almost Certainly False" - suggests that many advocates of the sciences worry about any book that might give comfort to the enemy.

A siege mentality can make us distrustful of everyone, and especially of our critics, no matter how friendly. Dyson, Krauss, and others inclined to sideline the humanities would do well to remember that the humanities give them the tools with which to reason and write about the discoveries of science. If those of us in the humanities seem critical of the sciences, this doesn't mean we're unfriendly. The funny thing about Feynman's dictum is that as long as birds and people try to live together, birds actually do benefit from ornithologists. After all, ornithologists study the birds and their environments, and work to ensure that others see how important it is to preserve them. Of course, the birds in their daily lives will likely never know it.

I should add that philosophers like me benefit from ornithologists, too. I am especially grateful for the ornithologists at Cornell University for putting so much helpful information on their website for bird-watchers and ornithophiles like me.

The bird I have identified as a Cooper's hawk might be a sharp-shinned hawk; I often have trouble distinguishing them. We live on the migration path for ruby-throated hummingbirds, so we see them for two brief seasons, once in the spring and again in the fall. Mourning doves are notoriously poor parents, and we often find they've laid eggs in silly places. Fortunately for their species, they can produce multiple clutches each year.

If you're interested in both birds and philosophy, let me recommend Charles Hartshorne's book Why Birds Sing. Hartshorne suggests that maybe birds sing because they enjoy it. This may seem so obvious as to be silly, but it is a helpful addition to the usual claims that birds sing because singing is useful for mating, staking territorial claims, self-defense, and so on. Hartshorne doesn't allow us to reduce birds to bird-making machines. Which is helpful, because it's a reminder that we, too, are more than human-making machines. It's also good to be reminded that it's okay to sing for the sheer enjoyment of singing.

Do Birds Need Ornithologists?

|

| Cooper's hawk in my backyard. |

Feynman was just talking about philosophers of science, which is just one narrow slice of the philosophic pie. More recently others, like Freeman Dyson, have made broader indictments of philosophy, or like Lawrence Krauss, of the humanities generally.

Dyson, in an article he wrote for the New York Review of Books, described today's philosophers as "a sorry bunch of dwarfs. They are thinking deep thoughts and giving scholarly lectures to academic audiences, but hardly anybody in the world outside is listening. They are historically insignificant." Yes, we have a technical vocabulary that outsiders often have trouble understanding. But that's true of every discipline. And yes, we don't seem to have anyone in our discipline who is writing the next Job or Republic right now, but that's been true almost always. No discipline consistently produces nothing but geniuses. Many of us in every discipline live our careers out bearing the gifts of the past forward to another generation so that they might benefit from them and add to them. And many of us are content to be forgotten as long as the books of wisdom entrusted to us are remembered.

|

| Female ruby-throated hummingbird. |

In his recent book A Universe From Nothing, Krauss seems to be at pains to point out that without the sciences, the humanities are virtually useless, and that even with the sciences, the humanities are still virtually useless. His introduction pushes the humanities back at arm's length and invites them to clear out while science handles all the real heavy lifting.

What stands out for me as I read these scientists and some others writing in a similar vein is that they write like they're on the defensive and feeling embattled. My guess is that they see themselves or their disciplines as being engaged in an important fight about cultural values, science education, and research funding. The outsized reaction to Thomas Nagel's recent Mind and Cosmos - with its inflammatory subtitle, "Why The Materialist Neo-Darwinian Conception of Nature Is Almost Certainly False" - suggests that many advocates of the sciences worry about any book that might give comfort to the enemy.

|

| Mourning dove eggs in one of my flower pots. |

******

I should add that philosophers like me benefit from ornithologists, too. I am especially grateful for the ornithologists at Cornell University for putting so much helpful information on their website for bird-watchers and ornithophiles like me.

The bird I have identified as a Cooper's hawk might be a sharp-shinned hawk; I often have trouble distinguishing them. We live on the migration path for ruby-throated hummingbirds, so we see them for two brief seasons, once in the spring and again in the fall. Mourning doves are notoriously poor parents, and we often find they've laid eggs in silly places. Fortunately for their species, they can produce multiple clutches each year.

If you're interested in both birds and philosophy, let me recommend Charles Hartshorne's book Why Birds Sing. Hartshorne suggests that maybe birds sing because they enjoy it. This may seem so obvious as to be silly, but it is a helpful addition to the usual claims that birds sing because singing is useful for mating, staking territorial claims, self-defense, and so on. Hartshorne doesn't allow us to reduce birds to bird-making machines. Which is helpful, because it's a reminder that we, too, are more than human-making machines. It's also good to be reminded that it's okay to sing for the sheer enjoyment of singing.

∞

Evolution and Education

Sometimes I meet students who are afraid that evolutionary science poses a threat to their belief in God. I think it is helpful for them to ask themselves this question:

Of course, this doesn't clear up all the obstacles to reconciling religious belief and confidence in science, but it's a start.

If you're a teacher of students who also grapple with this, and you don't understand them, this might help. Some of them will certainly be unreasonable. For them, sometimes all you can do is be an example of reasonable beliefs and hope it sinks in someday. But many of them are concerned about a few big questions, like these:

Acknowledging your students' concerns will help them to see that you care about them as people and not just as names or numbers on a page. Which will already begin to address their deepest concerns.Is God capable of creating through natural processes?There are only two answers to this question. If you say no, you make God too small to be worth worshiping. If you say yes, then you see that there's no prima facie reason why belief in God and belief in evolution need to be opposed to one another.

Of course, this doesn't clear up all the obstacles to reconciling religious belief and confidence in science, but it's a start.

*****

*****

If you're a teacher of students who also grapple with this, and you don't understand them, this might help. Some of them will certainly be unreasonable. For them, sometimes all you can do is be an example of reasonable beliefs and hope it sinks in someday. But many of them are concerned about a few big questions, like these:

∞

Future Hopes, Present Experience, and the Wisdom of the Past

A reflection on Henry Bugbee's Inward Morning, his entry dated Friday, September 5.

Bugbee writes: "Of experience...we may hope for understanding in our own time, and in this we do not seem to have the edge on preceding generations of men."

Science grows from one generation to another. What we know is more advanced than what previous generations knew. But precisely because of this, we are alienated from what science will know, what it aims to know when it reaches its goal. Science uses experience, it swims in the medium of experience on a long-distance swim. We are like generations of migratory butterflies, none of us making the whole journey, but each of us making part of it so that the next generation may fly further. Standing on one another's shoulders we become the giants upon whose shoulders our intellectual descendants may stand.

At first blush, experience seems less worth knowing, since it is subjective, unquantifiable, subject to the winds of time and the diurnal tides of the chemistry of our blood. But experience is immediate. No generation is privileged; every generation receives the same share. Here our knowledge is not a deposit that we hope will gain interest for our children; it is something in our hands and for us now. The wisdom of the past does not advance the next generation so much as clarify our own.

Bugbee again: "It is not a question of our beginning from where they leave off and going on to supersede them. We are fortunate if we can become communicant in our own way with what they have to say."

Tradition has roots that mean handed-down. Bugbee reminds me, gives me words to articulate, why it is worth continuing to try to read ancient wisdom. He reminds me why, when I could have chosen to work in science, it is not a bad choice to work as a teacher, priest, curator, historian, poet, librarian - a custodian of the narratives of experience. Science aims forward beyond our lives; but experience is here now, where we live. Is it such a bad thing to live here and now?

Bugbee writes: "Of experience...we may hope for understanding in our own time, and in this we do not seem to have the edge on preceding generations of men."

Science grows from one generation to another. What we know is more advanced than what previous generations knew. But precisely because of this, we are alienated from what science will know, what it aims to know when it reaches its goal. Science uses experience, it swims in the medium of experience on a long-distance swim. We are like generations of migratory butterflies, none of us making the whole journey, but each of us making part of it so that the next generation may fly further. Standing on one another's shoulders we become the giants upon whose shoulders our intellectual descendants may stand.

At first blush, experience seems less worth knowing, since it is subjective, unquantifiable, subject to the winds of time and the diurnal tides of the chemistry of our blood. But experience is immediate. No generation is privileged; every generation receives the same share. Here our knowledge is not a deposit that we hope will gain interest for our children; it is something in our hands and for us now. The wisdom of the past does not advance the next generation so much as clarify our own.

Bugbee again: "It is not a question of our beginning from where they leave off and going on to supersede them. We are fortunate if we can become communicant in our own way with what they have to say."

Tradition has roots that mean handed-down. Bugbee reminds me, gives me words to articulate, why it is worth continuing to try to read ancient wisdom. He reminds me why, when I could have chosen to work in science, it is not a bad choice to work as a teacher, priest, curator, historian, poet, librarian - a custodian of the narratives of experience. Science aims forward beyond our lives; but experience is here now, where we live. Is it such a bad thing to live here and now?

∞

Puritans and Vaccinations

In light of recent political debates in the United States, this seems worth noting: the Puritan divine Jonathan Edwards died of smallpox on March 22, 1758. His death was the result of a bad inoculation, which is, of course, tragic. But it is worth remembering that he received the inoculation to protect himself from the disease, and, apparently, as a way of showing that he thought the science behind it was trustworthy enough to take a risk and set an example for others. We sometimes think of Puritans as being benighted, ignorant and pathologically anhedonic. Edwards' active intellect and his attention to the works of John Locke and Isaac Newton suggest that this description of Puritans is facile and false. (Thanks for nothing, H.L. Mencken.)

Of course, there are other issues at stake here, like the ethical question of whether vaccines should ever be mandated, and whether the facts about the HPV vaccine are being reported accurately.

But what strikes me about Edwards' death is the possibility that in choosing to receive a vaccine, Edwards risked--and lost--his own life for the sake of others. I would not require others to follow his example, but I think that Christians (and especially those who revere the memory of the Puritans) might take his example to heart.

Of course, there are other issues at stake here, like the ethical question of whether vaccines should ever be mandated, and whether the facts about the HPV vaccine are being reported accurately.

But what strikes me about Edwards' death is the possibility that in choosing to receive a vaccine, Edwards risked--and lost--his own life for the sake of others. I would not require others to follow his example, but I think that Christians (and especially those who revere the memory of the Puritans) might take his example to heart.

∞

Wittgenstein, contra Hawking

Stephen Hawking recently said that philosophy is "dead" because it simply hasn't kept up with science in recent years. Hawking is not the first to make this sort of charge. A number of people have written replies to Hawking's charge, and I won't cover that ground again. Instead, let me simply offer a reply from Wittgenstein:

“Philosophy has made no progress? If somebody scratches where it itches, does that count as progress? If not, does that mean it wasn’t an authentic scratch? Not an authentic itch? Couldn’t this response to the stimulus go on for a long time until a remedy for itching is found?”

“Philosophy has made no progress? If somebody scratches where it itches, does that count as progress? If not, does that mean it wasn’t an authentic scratch? Not an authentic itch? Couldn’t this response to the stimulus go on for a long time until a remedy for itching is found?”