Scott Russell Sanders

∞

On Telling Stories

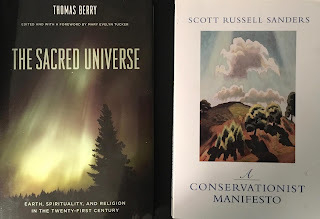

Posted for your consideration; words from two authors whose writing I find helpful, followed by a little commentary from me.

“Knowing on some intuitive level that we humans are guided by story, he ultimately called for the telling of the universe story. He felt that it was only in such a comprehensive scale that we could situate ourselves fully. His great desire was to see where we have come from and where we are going amid ecological destruction and social ferment. It was certainly an innovative idea, to announce the need for a new story that integrated the scientific understanding of evolution with its significance for humans. This is what he found so appealing in Teilhard’s seminal work."

“I’m one who dwells outside the camp of literary theory—so far outside that I can’t pretend to know much of what goes on there. I know scarcely more about deconstruction or postmodernism, say, than bumblebees and hummingbirds know about engineering. I don’t mean to brag of my ignorance nor to apologize for it, but only to explain why I’m not equipped to engage in debates about literary theory. What I can do is express my own faith in storytelling as a way of seeking the truth. And I can say why I believe we’ll continue to live by stories—grand myths about the whole of things as well as humble tales about the commonplace—as long as we have breath.”

A few years ago my wife and I, along with another family at our university, established a scholarship for Native American and First Nations students who wish to study to become storytellers. (Feel free to add to it by giving here if you are so inclined.)

Some people have since asked us why we did not invest our money in something more practical like helping individual students get into business or medical school. After all, that's where the money is, and higher income can correspond to greater independence and greater influence.

We see their point, but we both have committed ourselves to what might be considered storytelling disciplines because we think that stories shape lives and communities. A free society depends on good investigative journalists, good attorneys, and good public schools. A thriving society depends as well on good art and literature. And while religion has its downsides, it also has very strong upsides, and communities draw great benefit from healthy faith communities that remind us of our values, that give us places to congregate, to engage in commentary and contemplation, to welcome new life, to sustain commitments, to help us to mourn.

We often talk about the importance of STEM disciplines and healthcare, but I think we would do well to pay a little more attention to the way that good storytelling shapes healthcare (and the way bad storytelling makes us doubt good health practices like vaccination, for instance.)

I am persuaded that stories shape communities. They take what we have received from the past and transform and transmit it. If I am right, then I am prudent to invest in good storytelling. In the case of Native American and First Nations communities, I know just enough to know that there's a lot I don't know. And I'd like to know more.

I've been working with Bio-Itzá, a small Maya Itzá environmental group in Guatemala for the last decade, and I am constantly learning from the stories of their few surviving elders who grew up hearing the Itzá language spoken. The preservation of those words and stories means not just the preservation of a few tall tales, but the preservation of everything that is encoded and deeply rooted in those stories. The stories are cultural and ecological palimpsests, and when the Itzá elders tell them, they are passing on far more than mere words.

So my wife and I are committed to helping others to tell their stories. Because "we are guided by story," and "storytelling [is] a way of seeking the truth," and "we'll continue to live by stories."

“Knowing on some intuitive level that we humans are guided by story, he ultimately called for the telling of the universe story. He felt that it was only in such a comprehensive scale that we could situate ourselves fully. His great desire was to see where we have come from and where we are going amid ecological destruction and social ferment. It was certainly an innovative idea, to announce the need for a new story that integrated the scientific understanding of evolution with its significance for humans. This is what he found so appealing in Teilhard’s seminal work."

-- Mary Evelyn Tucker, in her preface to Thomas Berry’s The Sacred Universe. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009) (emphasis is mine)

“I’m one who dwells outside the camp of literary theory—so far outside that I can’t pretend to know much of what goes on there. I know scarcely more about deconstruction or postmodernism, say, than bumblebees and hummingbirds know about engineering. I don’t mean to brag of my ignorance nor to apologize for it, but only to explain why I’m not equipped to engage in debates about literary theory. What I can do is express my own faith in storytelling as a way of seeking the truth. And I can say why I believe we’ll continue to live by stories—grand myths about the whole of things as well as humble tales about the commonplace—as long as we have breath.”

-- Scott Russell Sanders, A Conservationist Manifesto. (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2009) (emphasis is mine)

*****

A few years ago my wife and I, along with another family at our university, established a scholarship for Native American and First Nations students who wish to study to become storytellers. (Feel free to add to it by giving here if you are so inclined.)

Some people have since asked us why we did not invest our money in something more practical like helping individual students get into business or medical school. After all, that's where the money is, and higher income can correspond to greater independence and greater influence.

We see their point, but we both have committed ourselves to what might be considered storytelling disciplines because we think that stories shape lives and communities. A free society depends on good investigative journalists, good attorneys, and good public schools. A thriving society depends as well on good art and literature. And while religion has its downsides, it also has very strong upsides, and communities draw great benefit from healthy faith communities that remind us of our values, that give us places to congregate, to engage in commentary and contemplation, to welcome new life, to sustain commitments, to help us to mourn.

We often talk about the importance of STEM disciplines and healthcare, but I think we would do well to pay a little more attention to the way that good storytelling shapes healthcare (and the way bad storytelling makes us doubt good health practices like vaccination, for instance.)

I am persuaded that stories shape communities. They take what we have received from the past and transform and transmit it. If I am right, then I am prudent to invest in good storytelling. In the case of Native American and First Nations communities, I know just enough to know that there's a lot I don't know. And I'd like to know more.

I've been working with Bio-Itzá, a small Maya Itzá environmental group in Guatemala for the last decade, and I am constantly learning from the stories of their few surviving elders who grew up hearing the Itzá language spoken. The preservation of those words and stories means not just the preservation of a few tall tales, but the preservation of everything that is encoded and deeply rooted in those stories. The stories are cultural and ecological palimpsests, and when the Itzá elders tell them, they are passing on far more than mere words.

So my wife and I are committed to helping others to tell their stories. Because "we are guided by story," and "storytelling [is] a way of seeking the truth," and "we'll continue to live by stories."

∞

Reason For Hope

Nearly every spring term I teach a class called “Theology and Philosophy in Dialogue.” I inherited the title and the course description when I started teaching at my current school in 2005. Each year the course changes a little, in response to my students and what I perceive to be relevant themes in our world and culture.

Apologetics and Postmodernism

When I first taught it, I made it a class about apologetics and postmodernism. By “apologetics” I mean the work of giving a reasoned account of one’s commitments; by “postmodernism,” I mean the suspicion that what look like reasoned accounts might have unexamined depths and layers to them. In the context of theism—and in particular Christian theism—apologetics has a long history that reaches back to the early years of Christianity. Saint Peter wrote in his longer letter that Christians should always be prepared to give a reasoned defense of the hope they bore within them. That phrase “reasoned defense” is a translation of the Greek word apologia, which can mean a legal defense, and from which we get our word “apologetics.”

When Saint Paul of Tarsus found himself in Athens, speaking to Stoic and Epicurean philosophers on the Areopagus, he tried to explain his beliefs not in the terms of his culture but in theirs. He doesn’t seem to have won many over to his views that day, but if nothing else was accomplished, at the end of the conversation it was clearer where Paul and the Greek philosophers were in agreement and where they disagreed. If immediate conversion was the aim of his speech, it wasn’t a great speech. But if he aimed to build a bridge of mutual understanding, I’d say he was pretty successful.

One of the keys to his success, I think, was familiarity with the culture around him. I’ve written about this elsewhere, so I won’t belabor it here, but I’ll just point out that Paul quoted two Greek philosophical poets, Epimenides and Aratos, and he did so in a culturally appropriate and significant place, since several centuries before Paul’s travels, Epimenides (who was from Crete) also traveled to Athens and also spoke on the Areopagus about the gods and salvation.

Understanding Atheism(s)

A few years after I started teaching that course, I shifted the course to take seriously the “New Atheists.” I figured that if my religious students graduated without hearing the strongest challenges to their faith, I, as a professor who teaches theology, was letting them down. I wanted them to know that soon they’d hear strong arguments against their religious heritage, beliefs, and practices, and that these arguments should be taken seriously. For my Christian students, I framed this as a way of living the commandment to love God with one’s mind.

Of course, only some of my students are religious, and some of the religious students aren’t Christians. (I’m at a Lutheran university in a small Midwestern city, so until recently most of them were at least culturally Christian; that’s changing quickly, though.) I wanted this to be a class that was helpful for everyone, so I started to turn this into a class about mutual understanding. I now teach my students how to distinguish between a dozen different kinds of (and reasons for) atheism, lest they make the mistake of oversimplifying the complexity of their neighbors and of themselves.

Understanding and Agapic Love

Arguments about religion can quickly become unkind. Many of us have been wounded in the name of religion, and those wounds heal slowly, if at all. How could we make this into a class that was—on its surface, and in its content—about theology and philosophy, while really making it about something like mutual care?

I just mentioned that great commandment: Love God with your heart, soul, mind, and strength, Jesus said, echoing Moses. Then he added a second commandment: love your neighbor as yourself. Everything else hangs on these two commandments, he said.

Explaining those two commandments would be almost as hard as trying to keep them, so I won’t try to do so here. I’ll just point out that it’s fascinating to command someone to love someone else; that the love that’s called for here is agapic love, i.e. the love that seeks the good and flourishing of the beloved; and that the commandments are so lacking in specificity as to call for both extensive commentary and continued practice. They’re vague commandments, which means they require us to work them out in community, over time. And in all likelihood we’ll never get them right. That may seem like a weakness, but it also strikes me as offering the freedom to try and to fail and to help one another to try again.

Anxiety, Ultimate Concerns, and Societal “Stress Fractures”

Which brings me to the most recent incarnation of my Theology and Philosophy in Dialogue class. Over the last few years it seems to me that my students have become more anxious about their economic futures, more stressed about exams and jobs, more focused on education and work as competition for rank. I could be wrong, but as the stress and anxiety have grown, it seems like my students are so busy jockeying for position that they have a hard time putting the cause of their stress into words. On top of all this, here in the United States, it feels like we’ve been using stronger words so that we can give voice to our anxiety more quickly. We aren’t broken, but we’ve got lots of hairline stress fractures that are too small to see. We aren’t bleeding, but we’ve got a constant dull ache.

In other words, it seems like we’re fearful without being able to identify the object of our fear, and that has us prepared to see enemies wherever we look. This does not make it easy to love our neighbors as ourselves (unless we also have that kind of distrust of ourselves, which is a real possibility, I suppose.) And at least in the way Paul Tillich described God: whatever we regard as our ultimate concern functions as our God. When economic anxiety, jostling for rank, or fear of losing one’s place in the future, (these are all ways of saying the same thing, I think) take on the role of “ultimate concern” in our lives, they become our gods.

The course I’m teaching this semester still has traces of every previous semester’s influences. We talk a little about apologetics, and that’s a helpful way of teaching students about logic, inference, probability, and certainty. (Ask some of them about “doxastic certainty” or my “haystack problem” and you’ll see what I mean.)

And we still talk about postmodernism, though as my career has shifted from the philosophy of religion to environmental philosophy, ethics, and policy, I’m inclined to follow Scott Russell Sanders’ view (see note, below) that if we spend too much time theorizing and not enough time caring for the world we share, incredulity towards metanarratives can quickly become a new metanarrative that we fail to examine sufficiently.

And we still talk about atheisms. This semester I have sketched a dozen forms of atheism once again, and we’re now working our way through them.

Friendship, and “Best Construction”

But the aim of the class, more than anything, is friendship.

I told all the students that this was the case on the first day of class.

And here, I think, is where Theology and Philosophy can have a really helpful dialogue in our time. I teach at a Lutheran university, so it’s fitting to invoke Luther. In his Small Catechism, he offers some commentary on the Ten Commandments. His commentary on the eighth commandment is helpful. The commandment reads simply, like this:

This is hard.

“A Mutual, Joint-Stock World, In All Meridians”

It’s especially hard when we feel that others are getting ahead of us, and that we are in a competition with everyone else. If the world is a zero-sum game, then everyone run, and the Devil take the hindmost. But what if Queequeg is right? When Queequeg sees a fellow sailor drowning and no one moves to save the sailor, Queequeg leaps into the water to save his fellow. There is no question of whether they are of the same tribe, the same party, the same race, the same team. Queequeg is, as far as anyone aboard the ship knows, a cannibal. And yet the narrator, observing Queequeg’s agapic care for his fellow sailor, offers this comment:

It’s much easier to approach theological conversations with the idea that our theology is a weapon and that our enemies are those with whom we disagree. It’s so easy to forget what Saint Paul wrote, that we don’t fight against flesh and blood, but against far less tangible, invisible forces that would have us view our neighbors with malice.

Could we approach theology the way Queequeg approaches the plight of his fellow sailor? Is it possible to maintain one’s cherished beliefs while recognizing that one’s object of “ultimate concern” might be something we don’t yet see with certainty and clarity? I cannot speak for others, so I’ll just offer this confession: I’m aware of a capacity in myself to care more for my theology than for the God that my theology claims to describe. In simpler terms: my own theology can become so dear to me that it becomes an idol, displacing the very God I set out to love and serve. And how to I love and serve my God? So far, the best I can offer you is this: I should love God with all I am, and I should love my neighbor as myself. Does that seem unclear to you? It does to me. Which means I need all the help I can get in clarifying my vision. Right now I see in a glass, darkly.

The philosopher Jonathan Lear suggests a principle akin to Queequeg’s, and to Luther’s: the principle of humanity. He describes it like this:

Conclusion

It’s appropriate to me that I teach this course in Lent each year. Lent is a good time for self-examination, and that includes an examination of all kinds of pieties and supposed certainties. What is it that we hold to be of ultimate concern? What do we love with all our heart, soul, mind, and strength? That might just be playing the role of a god in our lives. If so, does that God help us to love our neighbors as ourselves?

I could be wrong in all I say in this class. I enter it with “fear and trembling,” knowing that there’s so much I don’t know, and knowing that many of my students might be wiser than I am. I know they might have seen the divine far more clearly than I ever will in this life.

But oh, how I want them to live well, not to be entangled by anxious grief, not to be afraid of the future, not to be burdened by relentless suspicions and fears.

Yes, there are other subjects I could teach, and yes, there are other jobs I could do. But for me, right now, this one feels like a good way to reexamine my own ultimate concerns, and a good way to help others to do the same. May I do so without malice, with agapic love, and with the constant practice of putting the best construction on everything.

Amen. Lord, have mercy.

*****

Notes:

* Scott Russell Sanders: I'm thinking of his essay, "The Warehouse and the Wilderness," and in particular the opening pages of that essay. You can find it in A Conservationist Manifesto, beginning on page 71. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009)

* Ulpian's words are cited in Justinian, Institutes, Book 1, Title 1, Sec. 3.

* Lear has an endnote at the end of this sentence. It reads: “This principle is also known as the ‘principle of charity,’ and the most famous arguments for it are given by Donald Davidson. See his “Radical Interpretation,” in Inquiries Into Truth And Interpretation (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984), pp. 136-137; “Belief and the Basis of Meaning,” ibid., pp. 152-153; “Thought and Talk,” ibid., pp. 168-169; “On the Very Idea of a Conceptual Scheme,” ibid., pp. 196-197; “The Method of Truth in Metaphysics,” ibid., pp. 200-201.”

Apologetics and Postmodernism

When I first taught it, I made it a class about apologetics and postmodernism. By “apologetics” I mean the work of giving a reasoned account of one’s commitments; by “postmodernism,” I mean the suspicion that what look like reasoned accounts might have unexamined depths and layers to them. In the context of theism—and in particular Christian theism—apologetics has a long history that reaches back to the early years of Christianity. Saint Peter wrote in his longer letter that Christians should always be prepared to give a reasoned defense of the hope they bore within them. That phrase “reasoned defense” is a translation of the Greek word apologia, which can mean a legal defense, and from which we get our word “apologetics.”

When Saint Paul of Tarsus found himself in Athens, speaking to Stoic and Epicurean philosophers on the Areopagus, he tried to explain his beliefs not in the terms of his culture but in theirs. He doesn’t seem to have won many over to his views that day, but if nothing else was accomplished, at the end of the conversation it was clearer where Paul and the Greek philosophers were in agreement and where they disagreed. If immediate conversion was the aim of his speech, it wasn’t a great speech. But if he aimed to build a bridge of mutual understanding, I’d say he was pretty successful.

One of the keys to his success, I think, was familiarity with the culture around him. I’ve written about this elsewhere, so I won’t belabor it here, but I’ll just point out that Paul quoted two Greek philosophical poets, Epimenides and Aratos, and he did so in a culturally appropriate and significant place, since several centuries before Paul’s travels, Epimenides (who was from Crete) also traveled to Athens and also spoke on the Areopagus about the gods and salvation.

Understanding Atheism(s)

A few years after I started teaching that course, I shifted the course to take seriously the “New Atheists.” I figured that if my religious students graduated without hearing the strongest challenges to their faith, I, as a professor who teaches theology, was letting them down. I wanted them to know that soon they’d hear strong arguments against their religious heritage, beliefs, and practices, and that these arguments should be taken seriously. For my Christian students, I framed this as a way of living the commandment to love God with one’s mind.

Of course, only some of my students are religious, and some of the religious students aren’t Christians. (I’m at a Lutheran university in a small Midwestern city, so until recently most of them were at least culturally Christian; that’s changing quickly, though.) I wanted this to be a class that was helpful for everyone, so I started to turn this into a class about mutual understanding. I now teach my students how to distinguish between a dozen different kinds of (and reasons for) atheism, lest they make the mistake of oversimplifying the complexity of their neighbors and of themselves.

Understanding and Agapic Love

Arguments about religion can quickly become unkind. Many of us have been wounded in the name of religion, and those wounds heal slowly, if at all. How could we make this into a class that was—on its surface, and in its content—about theology and philosophy, while really making it about something like mutual care?

I just mentioned that great commandment: Love God with your heart, soul, mind, and strength, Jesus said, echoing Moses. Then he added a second commandment: love your neighbor as yourself. Everything else hangs on these two commandments, he said.

Explaining those two commandments would be almost as hard as trying to keep them, so I won’t try to do so here. I’ll just point out that it’s fascinating to command someone to love someone else; that the love that’s called for here is agapic love, i.e. the love that seeks the good and flourishing of the beloved; and that the commandments are so lacking in specificity as to call for both extensive commentary and continued practice. They’re vague commandments, which means they require us to work them out in community, over time. And in all likelihood we’ll never get them right. That may seem like a weakness, but it also strikes me as offering the freedom to try and to fail and to help one another to try again.

Anxiety, Ultimate Concerns, and Societal “Stress Fractures”

Which brings me to the most recent incarnation of my Theology and Philosophy in Dialogue class. Over the last few years it seems to me that my students have become more anxious about their economic futures, more stressed about exams and jobs, more focused on education and work as competition for rank. I could be wrong, but as the stress and anxiety have grown, it seems like my students are so busy jockeying for position that they have a hard time putting the cause of their stress into words. On top of all this, here in the United States, it feels like we’ve been using stronger words so that we can give voice to our anxiety more quickly. We aren’t broken, but we’ve got lots of hairline stress fractures that are too small to see. We aren’t bleeding, but we’ve got a constant dull ache.

In other words, it seems like we’re fearful without being able to identify the object of our fear, and that has us prepared to see enemies wherever we look. This does not make it easy to love our neighbors as ourselves (unless we also have that kind of distrust of ourselves, which is a real possibility, I suppose.) And at least in the way Paul Tillich described God: whatever we regard as our ultimate concern functions as our God. When economic anxiety, jostling for rank, or fear of losing one’s place in the future, (these are all ways of saying the same thing, I think) take on the role of “ultimate concern” in our lives, they become our gods.

The course I’m teaching this semester still has traces of every previous semester’s influences. We talk a little about apologetics, and that’s a helpful way of teaching students about logic, inference, probability, and certainty. (Ask some of them about “doxastic certainty” or my “haystack problem” and you’ll see what I mean.)

And we still talk about postmodernism, though as my career has shifted from the philosophy of religion to environmental philosophy, ethics, and policy, I’m inclined to follow Scott Russell Sanders’ view (see note, below) that if we spend too much time theorizing and not enough time caring for the world we share, incredulity towards metanarratives can quickly become a new metanarrative that we fail to examine sufficiently.

And we still talk about atheisms. This semester I have sketched a dozen forms of atheism once again, and we’re now working our way through them.

Friendship, and “Best Construction”

But the aim of the class, more than anything, is friendship.

I told all the students that this was the case on the first day of class.

And here, I think, is where Theology and Philosophy can have a really helpful dialogue in our time. I teach at a Lutheran university, so it’s fitting to invoke Luther. In his Small Catechism, he offers some commentary on the Ten Commandments. His commentary on the eighth commandment is helpful. The commandment reads simply, like this:

“Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor.”Like the other commandments I’ve mentioned, it is only a few words long. And like those others, it leaves room for commentary. Luther’s commentary does something that I find very helpful. While the commandment is negative (“thou shalt not,” it says) Luther thought that alongside each negative commandment was something positive. So he writes:

What does this mean?--Answer. We should fear and love God that we may not deceitfully belie, betray, slander, or defame our neighbor, but defend him, [think and] speak well of him, and put the best construction on everything.”This is akin to what Plato offers in several ways in his Republic, and to Ulpian’s legal principle of “giving to each person their due,” (see note, below) but it goes a little further, with an agapic tinge: Luther doesn’t just tell us not to lie, nor does he tell us to be simply honest, but to put the best construction on everything.

This is hard.

“A Mutual, Joint-Stock World, In All Meridians”

It’s especially hard when we feel that others are getting ahead of us, and that we are in a competition with everyone else. If the world is a zero-sum game, then everyone run, and the Devil take the hindmost. But what if Queequeg is right? When Queequeg sees a fellow sailor drowning and no one moves to save the sailor, Queequeg leaps into the water to save his fellow. There is no question of whether they are of the same tribe, the same party, the same race, the same team. Queequeg is, as far as anyone aboard the ship knows, a cannibal. And yet the narrator, observing Queequeg’s agapic care for his fellow sailor, offers this comment:

Was there ever such unconsciousness? He did not seem to think that he at all deserved a medal from the Humane and Magnanimous Societies. He only asked for water—fresh water—something to wipe the brine off; that done, he put on dry clothes, lighted his pipe, and leaning against the bulwarks, and mildly eyeing those around him, seemed to be saying to himself—“It’s a mutual, joint-stock world, in all meridians. We cannibals must help these Christians.” -- Herman Melville, Moby Dick. (New York: Signet, 1980) 76

It’s much easier to approach theological conversations with the idea that our theology is a weapon and that our enemies are those with whom we disagree. It’s so easy to forget what Saint Paul wrote, that we don’t fight against flesh and blood, but against far less tangible, invisible forces that would have us view our neighbors with malice.

Could we approach theology the way Queequeg approaches the plight of his fellow sailor? Is it possible to maintain one’s cherished beliefs while recognizing that one’s object of “ultimate concern” might be something we don’t yet see with certainty and clarity? I cannot speak for others, so I’ll just offer this confession: I’m aware of a capacity in myself to care more for my theology than for the God that my theology claims to describe. In simpler terms: my own theology can become so dear to me that it becomes an idol, displacing the very God I set out to love and serve. And how to I love and serve my God? So far, the best I can offer you is this: I should love God with all I am, and I should love my neighbor as myself. Does that seem unclear to you? It does to me. Which means I need all the help I can get in clarifying my vision. Right now I see in a glass, darkly.

The philosopher Jonathan Lear suggests a principle akin to Queequeg’s, and to Luther’s: the principle of humanity. He describes it like this:

“The interpretation thus fits what philosophers call the principle of humanity: that we should try to interpret others as saying something true—guided by our own sense of what is true and of what they could reasonably believe.” -- Jonathan Lear, Radical Hope. 4 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006) (See note below)The Episcopal Church’s Book of Common Prayer offers another commentary on the fourth commandment, the commandment not to take the name of God in vain. The Book of Common Prayer rephrases the commandment like this:

You shall not invoke with malice the Name of the Lord your God.

Amen. Lord have mercy.The rephrasing is a commentary on “in vain.” Invoking God’s name in vain is equated with invoking it with malice, that is, with the opposite of agapic love.

Conclusion

It’s appropriate to me that I teach this course in Lent each year. Lent is a good time for self-examination, and that includes an examination of all kinds of pieties and supposed certainties. What is it that we hold to be of ultimate concern? What do we love with all our heart, soul, mind, and strength? That might just be playing the role of a god in our lives. If so, does that God help us to love our neighbors as ourselves?

I could be wrong in all I say in this class. I enter it with “fear and trembling,” knowing that there’s so much I don’t know, and knowing that many of my students might be wiser than I am. I know they might have seen the divine far more clearly than I ever will in this life.

But oh, how I want them to live well, not to be entangled by anxious grief, not to be afraid of the future, not to be burdened by relentless suspicions and fears.

Yes, there are other subjects I could teach, and yes, there are other jobs I could do. But for me, right now, this one feels like a good way to reexamine my own ultimate concerns, and a good way to help others to do the same. May I do so without malice, with agapic love, and with the constant practice of putting the best construction on everything.

Amen. Lord, have mercy.

*****

Notes:

* Scott Russell Sanders: I'm thinking of his essay, "The Warehouse and the Wilderness," and in particular the opening pages of that essay. You can find it in A Conservationist Manifesto, beginning on page 71. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009)

* Ulpian's words are cited in Justinian, Institutes, Book 1, Title 1, Sec. 3.

* Lear has an endnote at the end of this sentence. It reads: “This principle is also known as the ‘principle of charity,’ and the most famous arguments for it are given by Donald Davidson. See his “Radical Interpretation,” in Inquiries Into Truth And Interpretation (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984), pp. 136-137; “Belief and the Basis of Meaning,” ibid., pp. 152-153; “Thought and Talk,” ibid., pp. 168-169; “On the Very Idea of a Conceptual Scheme,” ibid., pp. 196-197; “The Method of Truth in Metaphysics,” ibid., pp. 200-201.”

∞

Interview on SD Public Radio

Karl Gehrke interviewed me on SD Public Radio today about my new book. We talk about the book, brook trout, fly-fishing, hunting, raising children, and a handful of other topics with occasional nods to Heidegger and Bugbee, Kathleen Dean Moore, Scott Russell Sanders, and, of course, Thoreau.

Click here to listen to the whole interview.

Click here to listen to the whole interview.

∞

Augustine once said that a key to his conversion was when he met St Ambrose. Augustine had regarded the Bible as full of flawed and problematic texts. As Augustine put it, "by taking them literally, I had found them to kill."(1) Ambrose taught Augustine that the texts of the Bible may have more than one sense. The scriptures might speak to him in more than one way. When he heard this, and heard it from a man who thought it important to study science and the liberal arts, Augustine found his spiritual home in Christianity.

Augustine once said that a key to his conversion was when he met St Ambrose. Augustine had regarded the Bible as full of flawed and problematic texts. As Augustine put it, "by taking them literally, I had found them to kill."(1) Ambrose taught Augustine that the texts of the Bible may have more than one sense. The scriptures might speak to him in more than one way. When he heard this, and heard it from a man who thought it important to study science and the liberal arts, Augustine found his spiritual home in Christianity.

In recent years authors like Norman Wirzba, Bill McKibben, and Scott Russell Sanders have written about the relevance of Biblical texts for thinking about ecology. To me, they have been a little like St Ambrose. I've found one passage in Sanders to be quite helpful personally as I think about the management of my little suburban fifth-acre plot.

In his A Conservationist Manifesto, Sanders writes about the story of Noah and the Ark. He remembers that Noah was given the task of saving not just himself but every other species as well. And once they were on the ark, it was his job to care for the animals and to keep them alive. Sanders talks about books, and communities, and practices that can be like small arks in our time. One such "ark" may be the little plots of land we maintain around our homes:

*****

(1) Augustine, Confessions. Henry Chadwick's translation. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998) p. 88.

(2) Scott Russell Sanders, A Conservationist Manifesto. (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2009) p. 16.

*****

All of these images were taken by David O'Hara in the fall of 2013. You may use them elsewhere but please mention where you found them and give credit where it is due. Thanks.

My Backyard Ark

Augustine once said that a key to his conversion was when he met St Ambrose. Augustine had regarded the Bible as full of flawed and problematic texts. As Augustine put it, "by taking them literally, I had found them to kill."(1) Ambrose taught Augustine that the texts of the Bible may have more than one sense. The scriptures might speak to him in more than one way. When he heard this, and heard it from a man who thought it important to study science and the liberal arts, Augustine found his spiritual home in Christianity.

Augustine once said that a key to his conversion was when he met St Ambrose. Augustine had regarded the Bible as full of flawed and problematic texts. As Augustine put it, "by taking them literally, I had found them to kill."(1) Ambrose taught Augustine that the texts of the Bible may have more than one sense. The scriptures might speak to him in more than one way. When he heard this, and heard it from a man who thought it important to study science and the liberal arts, Augustine found his spiritual home in Christianity.In recent years authors like Norman Wirzba, Bill McKibben, and Scott Russell Sanders have written about the relevance of Biblical texts for thinking about ecology. To me, they have been a little like St Ambrose. I've found one passage in Sanders to be quite helpful personally as I think about the management of my little suburban fifth-acre plot.

In his A Conservationist Manifesto, Sanders writes about the story of Noah and the Ark. He remembers that Noah was given the task of saving not just himself but every other species as well. And once they were on the ark, it was his job to care for the animals and to keep them alive. Sanders talks about books, and communities, and practices that can be like small arks in our time. One such "ark" may be the little plots of land we maintain around our homes:

"Every unsprayed garden and unkempt yard, every meadow, marsh, and woods may become a reservoir for biological possibilities, keeping alive creatures who bear in their genes millions of years; worth of evolutionary discoveries. Every such refuge may also become a reservoir for spiritual possibilities, keeping alive our connection with the land, reminding us of our origins in the green world."(2)Lately I've been surveying my yard more closely, looking to see whom I'm sharing it with, and how. I've been trying to do some phenology, like Thoreau did. I also wander my garden with lenses: a hand lens for close inspection; my phone camera and my SLR for keeping records of what lives and grows there; and I've recently set up an infrared game camera to see who passes through at night. For the curious, I've posted some photos below of what I've seen there.

*****

(1) Augustine, Confessions. Henry Chadwick's translation. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998) p. 88.

(2) Scott Russell Sanders, A Conservationist Manifesto. (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2009) p. 16.

*****

All of these images were taken by David O'Hara in the fall of 2013. You may use them elsewhere but please mention where you found them and give credit where it is due. Thanks.

∞

Perpetual Motion

As the sun sets it sends its last rays shooting up from below the horizon to illuminate the undersides of contrails, the warp and weft of high-altitude aircraft that have crushed the air before them and left a trail of disturbance behind to mark their racing progress.

I myself am a frequent traveler. My far-flung family and my work as an educator, writer, and lecturer mean I am often in airports. At those times, I am mostly concerned with making my next flight. But when I gaze at the evening sky from my kitchen window and see the silver lines glowing over the setting sun, I wonder: where are we going? And why are we in such a hurry to get there?

Mise En Place

I recently read an interview with Scott Russell Sanders in the Englewood Review of Books. In it Sanders talks about the virtue of living in one place for a long time, of "Staying Put."

We Americans seem to be constantly on the move. We began as a nation of movers, and we have filled a continent by our frenetic motion.

When I took the job I currently have, my wife and I were moving to a part of the world we'd never even visited, the prairies of the upper midwest. We knew nobody here, had no roots here. We left our home and friends and family to find work, and we thought it would be a temporary assignment, a sojourn from which we would return to the place where we, like seeds from a tree, first fell to earth.

Little by little I am coming to think I am not on a sojourn here but am a transplant.

Taproots

I long for the mountains and clear streams of my youth. But when I think of myself as a temporary resident, I find it harder to put down taproots that can drink deeply from the waters that flow far underground.

The danger? Plants with shallow roots cannot weather droughts as well as those with deep roots. By analogy, as we commit ourselves to the place we live in, the more strength we can draw from that place.

And plants with taproots are good for the soil, too. They break the hard clay and bore holes into which the rain can sink deeply. Behold the lowly dandelion, the maker of topsoil. If I sink roots here, I'll make it more likely that my community will benefit from my presence.

This sinking of roots is hard to do. It can be hard because the culture may be different, for instance. Eight years into this gig, I still struggle with midwestern indirect communication, and with the very, very slow process of getting to know native midwesterners.

Weaving Our Hearts

Of course, being surrounded by others who are also on the move makes it hard, too. When I was in grad school one of our neighbors, Lisa, told us she could not be our friend because she knew we were only there for five years. We shared a backyard, and our children played together, but Lisa knew that too many times she had allowed her roots to grow into the lives of other mobile academics, and when they were uprooted, so was her heart. It hurt to hear her tell us that, but who could blame her?

And it is hard for me not to be near mountains. Sometimes, gazing out that kitchen window in the summertime I see great thunderheads low on the western horizon, gathering strength as they roll across the prairie towards Sioux Falls. My heart so longs for the mountains that nearly every time I see those thunderclouds I let myself believe for an instant that they are solid mountains, not ephemeral, gauzy clouds. I would sooner believe in a cataclysmic upheaval of the earth than believe I am without mountains forever.

Sometimes people here try to comfort me by telling me that here, in this same state, we have the Black Hills. I know they mean well, and I know it's a point of pride for them, but those mountains are over three hundred and fifty miles away. I cannot see them from here, and for some reason, that matters. It's like telling a hungry person to take heart, because somewhere else, somewhere not here, there is a banquet. It only makes the pangs sharper.

The Mountains Underground

My heart leans towards the mountains, but for today - the only day I have any control over, and a limited control, at that - I am trying to turn my feet into roots.

Years ago, when I was working in Poland, a friend brought me to a place called Tarnowska Góra. There's a silver mine under fairly flat ground there. Knowing that góra means "mountain," I asked her "Gdzie jest góra? Where is the mountain?" She smiled, and pointed down at her feet. "Underground," she said.

This is the image I am trying to cultivate: here there are mountains, too, but like the hidden thoughts of coy midwesterners, they are concealed by the superficial appearances.

These mountains under the prairie are not the Adirondacks of New York, or the bold Catskills fringing the Hudson River, whose heights cannot be avoided. They are not the Sangre de Cristo mountains or the Green Mountains or the Alleghenies, each of which have been my home, places where my children were born and raised. These subterranean mountains wait quietly beneath, supporting all things evenly, deeply rooted, immovable. I cannot gauge their height with my eye; I must measure it patiently, with my feet, by walking the slow prairie, by standing still. And, perhaps, though my heart is not yet ready to accept it, by letting my body one day be buried here, adding my small mass to these mountains, raising them incrementally by the simple height of my dormant bones.

But that is for another day. Today, I will walk, and let my feet learn to feel the mountains below.

All The Mountains Are Underground Here

|

| Sunset over the Yellowstone River |

As the sun sets it sends its last rays shooting up from below the horizon to illuminate the undersides of contrails, the warp and weft of high-altitude aircraft that have crushed the air before them and left a trail of disturbance behind to mark their racing progress.

I myself am a frequent traveler. My far-flung family and my work as an educator, writer, and lecturer mean I am often in airports. At those times, I am mostly concerned with making my next flight. But when I gaze at the evening sky from my kitchen window and see the silver lines glowing over the setting sun, I wonder: where are we going? And why are we in such a hurry to get there?

Mise En Place

I recently read an interview with Scott Russell Sanders in the Englewood Review of Books. In it Sanders talks about the virtue of living in one place for a long time, of "Staying Put."

We Americans seem to be constantly on the move. We began as a nation of movers, and we have filled a continent by our frenetic motion.

When I took the job I currently have, my wife and I were moving to a part of the world we'd never even visited, the prairies of the upper midwest. We knew nobody here, had no roots here. We left our home and friends and family to find work, and we thought it would be a temporary assignment, a sojourn from which we would return to the place where we, like seeds from a tree, first fell to earth.

Little by little I am coming to think I am not on a sojourn here but am a transplant.

Taproots

I long for the mountains and clear streams of my youth. But when I think of myself as a temporary resident, I find it harder to put down taproots that can drink deeply from the waters that flow far underground.

The danger? Plants with shallow roots cannot weather droughts as well as those with deep roots. By analogy, as we commit ourselves to the place we live in, the more strength we can draw from that place.

And plants with taproots are good for the soil, too. They break the hard clay and bore holes into which the rain can sink deeply. Behold the lowly dandelion, the maker of topsoil. If I sink roots here, I'll make it more likely that my community will benefit from my presence.

This sinking of roots is hard to do. It can be hard because the culture may be different, for instance. Eight years into this gig, I still struggle with midwestern indirect communication, and with the very, very slow process of getting to know native midwesterners.

Weaving Our Hearts

Of course, being surrounded by others who are also on the move makes it hard, too. When I was in grad school one of our neighbors, Lisa, told us she could not be our friend because she knew we were only there for five years. We shared a backyard, and our children played together, but Lisa knew that too many times she had allowed her roots to grow into the lives of other mobile academics, and when they were uprooted, so was her heart. It hurt to hear her tell us that, but who could blame her?

And it is hard for me not to be near mountains. Sometimes, gazing out that kitchen window in the summertime I see great thunderheads low on the western horizon, gathering strength as they roll across the prairie towards Sioux Falls. My heart so longs for the mountains that nearly every time I see those thunderclouds I let myself believe for an instant that they are solid mountains, not ephemeral, gauzy clouds. I would sooner believe in a cataclysmic upheaval of the earth than believe I am without mountains forever.

Sometimes people here try to comfort me by telling me that here, in this same state, we have the Black Hills. I know they mean well, and I know it's a point of pride for them, but those mountains are over three hundred and fifty miles away. I cannot see them from here, and for some reason, that matters. It's like telling a hungry person to take heart, because somewhere else, somewhere not here, there is a banquet. It only makes the pangs sharper.

The Mountains Underground

My heart leans towards the mountains, but for today - the only day I have any control over, and a limited control, at that - I am trying to turn my feet into roots.

|

| A picture of my heart: my boys, and mountains beneath them. |

Years ago, when I was working in Poland, a friend brought me to a place called Tarnowska Góra. There's a silver mine under fairly flat ground there. Knowing that góra means "mountain," I asked her "Gdzie jest góra? Where is the mountain?" She smiled, and pointed down at her feet. "Underground," she said.

This is the image I am trying to cultivate: here there are mountains, too, but like the hidden thoughts of coy midwesterners, they are concealed by the superficial appearances.

These mountains under the prairie are not the Adirondacks of New York, or the bold Catskills fringing the Hudson River, whose heights cannot be avoided. They are not the Sangre de Cristo mountains or the Green Mountains or the Alleghenies, each of which have been my home, places where my children were born and raised. These subterranean mountains wait quietly beneath, supporting all things evenly, deeply rooted, immovable. I cannot gauge their height with my eye; I must measure it patiently, with my feet, by walking the slow prairie, by standing still. And, perhaps, though my heart is not yet ready to accept it, by letting my body one day be buried here, adding my small mass to these mountains, raising them incrementally by the simple height of my dormant bones.

But that is for another day. Today, I will walk, and let my feet learn to feel the mountains below.