scripture

∞

Babel, in Paraphrase

Recently I have been wandering my city with a camera and sketchbook, looking at the ways our use and design of spaces speak about what we value.

Seeing often requires unhasty attention, or training, or both. I can't claim to have training in architecture, but I am trained in semiotics, and I suppose some of my grandfather's years as a toolmaker and my father's career as an engineer have rubbed off on me. Whatever the cause, I care about design.

The ancient story of the Tower of Babel (found in the eleventh chapter of the Book of Genesis) is also a story about design, and semiotics.

It's also a story worth unhasty attention. One hasty version goes roughly like this: everyone on earth shared a common language and common vocabulary. The people, moving to a new place, decided to build a tower to heaven, so they baked bricks and began to build. But they did not finish it; their language became many languages, and they spread out in many directions, divided from one another.

The Bible has a number of stories like this, short tales that seem to be making some simple and clear point. But as we ponder them unhastily - which is what theologians often do - we become more aware of how little we know. The obvious becomes the obscure, and the quotidien becomes mysterious.

A simple story becomes an invitation to slow down even more, and to consider. Selah, it says to us.

At first blush, the story of Babel appears to be a story of human hubris, and of God frustrating that hubris. It could be a simple parallel to the expulsion from Eden, or to the flooding of the earth in the story of Noah: there are limits, and if you transgress those limits, you will make your lot in life worse.

Lately, as I've slowed down my reading, I've been noticing something else: the bricks. The Bible does not often talk about the ethics of technology. There are passages that speak of things like the ethics of weaving, of sharing resources, and of the production, preparation, and distribution of food. But there are not many passages that name a particular human invention in the context of ethics. One of those inventions is named in several places: bricks.

The passage in Genesis 11 talks about bricks as a substitute for stone. When I was young I often worked as a stonemason and bricklayer. That experience may be what draws me to this passage. Bricks are easy to make, and easy to cut. We can standardize them, which makes building walls much faster.

The downside of bricks is related to their upside: they're easy to break, or to cut, or to erode. They don't last as long as stone, and if they're not well-reinforced, they are not as resilient against natural disasters. Some ancient stonemasons figured out how to cut and lay stones that can be jostled by an earthquake and then settle back into position, but bricks often collapse when the ground shakes beneath them. Bricks are easy to use, but they are not as reliable as stone. In comparison to many kinds of stone, bricks are a short-term investment.

This makes me wonder: what was the problem with the Tower of Babel? Was it the fact that the people were trying to build a tower to heaven? Or was it that they were trying to build one badly, or cheaply, or fast? Was it a problem of hubris, or a problem of materials and design? Genesis 11 does not answer that question directly. It leaves it as an open question for us.

Which is just what we should expect, if Genesis 11 conveys any truth. Think about this: how would this story have been told before the Tower of Babel was built? If the story is right, then before the Tower was built, the story would have been told in a language everyone would understand. But now that we have tried to build it (whatever that means) the story must be told in words that are confused, for people who are scattered and divided and who do not share vocabulary.

To paraphrase this: somehow, our use of bricks resulted in making it harder to connect with one another. And it's not clear how.

But somehow, it is a story that hundreds of generations have found worth repeating, even if our words fail to say with precision why that is so.

Maybe, just maybe, it has something to do with the way we continue to build walls of bricks. And what those bricks say about us, and what we value.

Since writing this, I started reading Christopher Alexander's book, The Timeless Way of Building, recommended to me by some friends in Sioux Falls. This line in particular stands out as serendipitous:

Seeing often requires unhasty attention, or training, or both. I can't claim to have training in architecture, but I am trained in semiotics, and I suppose some of my grandfather's years as a toolmaker and my father's career as an engineer have rubbed off on me. Whatever the cause, I care about design.

The ancient story of the Tower of Babel (found in the eleventh chapter of the Book of Genesis) is also a story about design, and semiotics.

It's also a story worth unhasty attention. One hasty version goes roughly like this: everyone on earth shared a common language and common vocabulary. The people, moving to a new place, decided to build a tower to heaven, so they baked bricks and began to build. But they did not finish it; their language became many languages, and they spread out in many directions, divided from one another.

The Bible has a number of stories like this, short tales that seem to be making some simple and clear point. But as we ponder them unhastily - which is what theologians often do - we become more aware of how little we know. The obvious becomes the obscure, and the quotidien becomes mysterious.

A simple story becomes an invitation to slow down even more, and to consider. Selah, it says to us.

At first blush, the story of Babel appears to be a story of human hubris, and of God frustrating that hubris. It could be a simple parallel to the expulsion from Eden, or to the flooding of the earth in the story of Noah: there are limits, and if you transgress those limits, you will make your lot in life worse.

The passage in Genesis 11 talks about bricks as a substitute for stone. When I was young I often worked as a stonemason and bricklayer. That experience may be what draws me to this passage. Bricks are easy to make, and easy to cut. We can standardize them, which makes building walls much faster.

The downside of bricks is related to their upside: they're easy to break, or to cut, or to erode. They don't last as long as stone, and if they're not well-reinforced, they are not as resilient against natural disasters. Some ancient stonemasons figured out how to cut and lay stones that can be jostled by an earthquake and then settle back into position, but bricks often collapse when the ground shakes beneath them. Bricks are easy to use, but they are not as reliable as stone. In comparison to many kinds of stone, bricks are a short-term investment.

*****

This makes me wonder: what was the problem with the Tower of Babel? Was it the fact that the people were trying to build a tower to heaven? Or was it that they were trying to build one badly, or cheaply, or fast? Was it a problem of hubris, or a problem of materials and design? Genesis 11 does not answer that question directly. It leaves it as an open question for us.

Which is just what we should expect, if Genesis 11 conveys any truth. Think about this: how would this story have been told before the Tower of Babel was built? If the story is right, then before the Tower was built, the story would have been told in a language everyone would understand. But now that we have tried to build it (whatever that means) the story must be told in words that are confused, for people who are scattered and divided and who do not share vocabulary.

To paraphrase this: somehow, our use of bricks resulted in making it harder to connect with one another. And it's not clear how.

But somehow, it is a story that hundreds of generations have found worth repeating, even if our words fail to say with precision why that is so.

Maybe, just maybe, it has something to do with the way we continue to build walls of bricks. And what those bricks say about us, and what we value.

*****

Update:Since writing this, I started reading Christopher Alexander's book, The Timeless Way of Building, recommended to me by some friends in Sioux Falls. This line in particular stands out as serendipitous:

"But in our time the languages have broken down. Since they are no longer shared, the processes which keep them deep have broken down: and it is therefore virtually impossible for anybody, in our time, to make a building live." (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979) p. 225

∞

When The Court Will Not Give Justice

“They suppressed their consciences and turned away their eyes from looking to Heaven or remembering their duty to administer justice.”

“Just as she was being led off to execution, God stirred up the holy spirit of a young lad named Daniel, and he shouted with a loud voice, ‘I want no part in shedding this woman’s blood!’ All the people turned to him and asked, ‘What is this you are saying?’ Taking his stand among hem he said, ‘Are you such fools, O Israelites, as to condemn a daughter of Israel without examination and without learning the facts? Return to court, for these men have given false evidence against her.’”

-- The Book of Susanna, v. 9. (New Revised Standard Version)

“Just as she was being led off to execution, God stirred up the holy spirit of a young lad named Daniel, and he shouted with a loud voice, ‘I want no part in shedding this woman’s blood!’ All the people turned to him and asked, ‘What is this you are saying?’ Taking his stand among hem he said, ‘Are you such fools, O Israelites, as to condemn a daughter of Israel without examination and without learning the facts? Return to court, for these men have given false evidence against her.’”

-- The Book of Susanna, vv. 45-49. (New Revised Standard Version)

∞

Written On The Skin

One of the peculiar things about teaching Greek and knowing several other ancient languages is that people often come to me seeking help with tattoos.

A few years ago a student named Brian came to me and asked "How do you say 'Suck Less' in Greek?" Apparently this was a phrase that his running coach said to his team to inspire them to run better.

As crude as the phrase is, I was intrigued by the problem of translation. "In order to translate the phrase I'd have to know what you mean by it," I replied. I spent a little while explaining how it would be possible to say, for instance, that an infant should nurse less; or that one should inhale less strongly. Or, if you pursue the more colloquial usage of the verb "suck," you might decide that it refers to poor behavior or - ahem - to a kind of erotic pleasure-giving in which the giver is thought to be demeaned by the giving.

Eventually I made the case that if you want to say it in Classical Greek, it would make sense to say it in a way that attended to the use of words in that language, and pointed him to Plutarch's Sayings of Spartan Women as a source of pithy sayings about living and acting strenuously. Ever since I took my first Greek class with Eve Adler at Middlebury College years ago, I've liked the phrase η ταν η επι τας, (at the link above, see #16 under "Other Spartan Women"; click on the Greek flag to see the full Greek text) which is often translated "Come back with your shield or upon it," meaning "Act virtuously in battle; either die with your weapons or win with your weapons, but do not throw them away in order to win your life at the expense of your virtue." I like the Greek phrase for its Laconian pithiness.

Of course, that one didn't quite make sense for a runner, so I showed him another from the same collection, κατα βημα της αρετης μεμνησο, or "With every step, remember [your] virtue." ("Virtue" is not a perfect translation; you could translate it as "excellence" also.)

Three years have passed since that conversation with Brian, but a few months ago he tracked me down and showed me his tattoo, which I rather like:

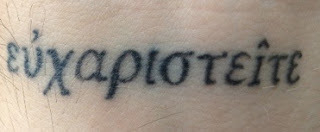

In a new twist, last year another student asked me to help him find the Greek verb "give thanks" as it appears in I Thessalonians 5.18. He didn't tell me what he planned to do with it, but when I saw him later that year at a wedding he showed me this, which he has tattooed on his wrist:

The word you see is ευχαριστειτε, related to our word "Eucharist" and the modern Greek ευχαριστω, meaning "I thank you."

I say this is a "new twist" because at least one passage in the Hebrew scriptures (Leviticus 19.28) appears to prohibit tattooing one's skin. Getting a tattoo, and in particular getting a tattoo of scripture, offers a bit of insight into one's hermeneutics. If the Gospels prohibited tattoos, I doubt many Christians would get them, but since the prohibition comes in the Hebrew scriptures, and since it seems to be tied to particular practices of worship or enslavement that no longer seem relevant, many young Christians are untroubled by it.

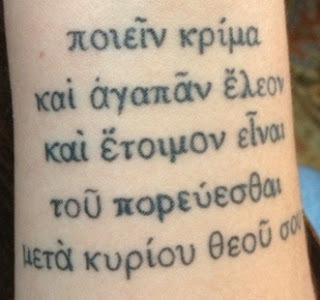

Recently one of my advisees showed me one of several tattoos she has recently acquired. This one is a longer Biblical text, from the prophet Micah, chapter 6, verse 8. I thought it interesting that she chose to get the Septuagint Greek rather than the Hebrew. She knows and translates Biblical (Koine) Greek and so I suppose she felt closer to that language. The text below means "...to do justice and to love mercy and to be ready/zealous to walk humbly with the Lord your God."

I like that verse quite a lot. If you don't know it, it begins by saying that this is what God asks of people. It's the sort of description that makes religion sound less like a burden and more like a description of a life well-lived.

I'm always reluctant to give advice about tattoos, because they're so permanent and so personal. And when I do give advice, I always want to write footnotes about regional dialects and historical and textual variants, or about the difficulties of translation. Quotes out of their native context so often seem lonely to me - such is my academic habit, of always seeing texts as living and moving and having their being* in nests and webs of other texts. Perhaps that's why I've never been inked myself, and I doubt I ever will get a "tat." I'm just not confident I've found words or an image that I'd want written on me forever. Sometimes that feels virtuous because it's prudent; other times I wonder if that's not a moral failing on my part, like I should be willing to commit to something. But I think for now I will remain uninked, and will continue to admire the commitments of my students.

* For example: I am borrowing this phrase ("live and move and have their being") from St Paul in Acts 17.28; he, in turn, appears to be borrowing it from Epimenides, who writes Εν αυτω γαρ ζωμεν και κινουμεθα και εσμεν. The phrase winds up being used in a number of other places, having been so eloquently translated into English by the King James Version of the Bible. See, for example, its use in the Book of Common Prayer, and in the first line of the hymn "We Come O Christ To Thee."

A few years ago a student named Brian came to me and asked "How do you say 'Suck Less' in Greek?" Apparently this was a phrase that his running coach said to his team to inspire them to run better.

As crude as the phrase is, I was intrigued by the problem of translation. "In order to translate the phrase I'd have to know what you mean by it," I replied. I spent a little while explaining how it would be possible to say, for instance, that an infant should nurse less; or that one should inhale less strongly. Or, if you pursue the more colloquial usage of the verb "suck," you might decide that it refers to poor behavior or - ahem - to a kind of erotic pleasure-giving in which the giver is thought to be demeaned by the giving.

Eventually I made the case that if you want to say it in Classical Greek, it would make sense to say it in a way that attended to the use of words in that language, and pointed him to Plutarch's Sayings of Spartan Women as a source of pithy sayings about living and acting strenuously. Ever since I took my first Greek class with Eve Adler at Middlebury College years ago, I've liked the phrase η ταν η επι τας, (at the link above, see #16 under "Other Spartan Women"; click on the Greek flag to see the full Greek text) which is often translated "Come back with your shield or upon it," meaning "Act virtuously in battle; either die with your weapons or win with your weapons, but do not throw them away in order to win your life at the expense of your virtue." I like the Greek phrase for its Laconian pithiness.

Of course, that one didn't quite make sense for a runner, so I showed him another from the same collection, κατα βημα της αρετης μεμνησο, or "With every step, remember [your] virtue." ("Virtue" is not a perfect translation; you could translate it as "excellence" also.)

Three years have passed since that conversation with Brian, but a few months ago he tracked me down and showed me his tattoo, which I rather like:

In a new twist, last year another student asked me to help him find the Greek verb "give thanks" as it appears in I Thessalonians 5.18. He didn't tell me what he planned to do with it, but when I saw him later that year at a wedding he showed me this, which he has tattooed on his wrist:

The word you see is ευχαριστειτε, related to our word "Eucharist" and the modern Greek ευχαριστω, meaning "I thank you."

I say this is a "new twist" because at least one passage in the Hebrew scriptures (Leviticus 19.28) appears to prohibit tattooing one's skin. Getting a tattoo, and in particular getting a tattoo of scripture, offers a bit of insight into one's hermeneutics. If the Gospels prohibited tattoos, I doubt many Christians would get them, but since the prohibition comes in the Hebrew scriptures, and since it seems to be tied to particular practices of worship or enslavement that no longer seem relevant, many young Christians are untroubled by it.

Recently one of my advisees showed me one of several tattoos she has recently acquired. This one is a longer Biblical text, from the prophet Micah, chapter 6, verse 8. I thought it interesting that she chose to get the Septuagint Greek rather than the Hebrew. She knows and translates Biblical (Koine) Greek and so I suppose she felt closer to that language. The text below means "...to do justice and to love mercy and to be ready/zealous to walk humbly with the Lord your God."

I like that verse quite a lot. If you don't know it, it begins by saying that this is what God asks of people. It's the sort of description that makes religion sound less like a burden and more like a description of a life well-lived.

I'm always reluctant to give advice about tattoos, because they're so permanent and so personal. And when I do give advice, I always want to write footnotes about regional dialects and historical and textual variants, or about the difficulties of translation. Quotes out of their native context so often seem lonely to me - such is my academic habit, of always seeing texts as living and moving and having their being* in nests and webs of other texts. Perhaps that's why I've never been inked myself, and I doubt I ever will get a "tat." I'm just not confident I've found words or an image that I'd want written on me forever. Sometimes that feels virtuous because it's prudent; other times I wonder if that's not a moral failing on my part, like I should be willing to commit to something. But I think for now I will remain uninked, and will continue to admire the commitments of my students.

*****

* For example: I am borrowing this phrase ("live and move and have their being") from St Paul in Acts 17.28; he, in turn, appears to be borrowing it from Epimenides, who writes Εν αυτω γαρ ζωμεν και κινουμεθα και εσμεν. The phrase winds up being used in a number of other places, having been so eloquently translated into English by the King James Version of the Bible. See, for example, its use in the Book of Common Prayer, and in the first line of the hymn "We Come O Christ To Thee."

*****

Update: a week or so after posting this I ran into the mother of one of the people whose tattoos are shown above. She thanked me, though I am not sure whether she was thanking me for helping her son get a tattoo, or for helping him to get the grammar right.

∞

Scripture's Trajectory: You Are Known; Be Holy

Everybody interprets texts. Interpreting texts means, among other things, determining the trajectory of the texts. Where are they coming from, and where do they point us?

When it comes to the Bible, we've all been shaped by it, and we all have ways of responding to the pressures it has exerted while shaping us.

The early creeds try to maintain considerable latitude for how we regard the scriptures. For instance, the Nicene Creed says "We believe in the Holy Spirit...who has spoken through the prophets." Just how has the Spirit spoken, and what are we to make of that?

I'm grateful for those early Christians who, like St. Augustine, acknowledged that the scripture may have several senses. The Spirit does not speak in monotone, but in harmony, and the scriptures may sing several parts at once.

I was born into a churchgoing family, but we didn't spend much time talking about scripture. As a teenager I joined an independent church with charismatic and evangelical theology, and it was there that some of my strongest impressions of scripture were formed, in the presence of people who believed that the Spirit's voice in scripture could still be heard timelessly. While I've since grown away from that church, the idea that God speaks through scripture has stuck with me.

So not only has it shaped my life indirectly, I have sought to make myself open to it, to let it teach and guide me. Its songs and poems comfort me in hard times, and give me words when I want to express my joy and gratitude. The prophets help me to name the compass-points toward which my heart stretches. Its narratives offer opportunities for reflection on lives lived well, and poorly. And while I've made no attempt to keep all of its commandments, I find in them rules and principles that help me to live a life of "long obedience," to borrow a phrase from Nietzsche.

They give me doctrines, too, ideas about the world that make sense to me and that I don't think I could have formulated on my own. Creation, fall, and redemption; nurturing love, sin, and grace. I doubt I could explain any of these in perfectly clear and agreeable terms, but even in their vague forms (perhaps especially in their vague forms) they help me to make sense of the world.

But there is more. I take the Bible to be not just a collection of books, but a collection that holds together. The Tower of Babel in Genesis and the Tongues of Fire in Acts go together just as the Garden of Eden, the Garden of Gethsemane, and the tree-lined streets of the New Jerusalem go together. The stories of fathers and sons from Adam to Abraham, from David to Joseph, all fit together like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle; no two are alike, but taken as a whole, a larger picture forms.

This, I believe, is why the work of studying scripture matters to the communities that claim to be people of those scriptures. Putting together the puzzle is the work of our lives together.

Which is not to say that I think God is a cruel puzzle-maker. To say that would be already to have sorted out the puzzle. I'm not fond of jigsaw puzzles--when I was younger I couldn't understand why I would purchase and subject myself to an unnecessary problem. Why not just buy the picture before it's cut up? But there is real joy in playfully and willingly choosing to tackle a problem together.

So here is my small contribution to our work together: I don't think the scriptures are simply about rules and doctrines. Let's assume that God inspired the Bible; if so, and if God only wanted to deliver doctrines, God is not a very good writer. There's a lot of fluff in there that doesn't contribute directly to our list of rules.

If, on the other hand, God wanted to create a community of love and wisdom, I'm not sure there's a better way than by giving stories and poems, and by getting personally involved in that community, sharing its joys and its sorrows and its work. And if God wanted to make people who would not just obey but grow up into love and wisdom, all the more so.

This is why I take the Bible to be giving us a set of narratives that hang together, forming not a complete story but a story that is like a set of signposts, or a finger pointing in the direction we should travel. We are not static automata, nor should we strive to be. We are pilgrims with progress yet to be made. As in the myth of Pygmalion and Galatea, a loving maker wants a lover, not a lifeless statue.

More than once I've heard facile criticisms* of the Bible saying, in effect, the Bible got slavery wrong, therefore the Bible is wrong. But this is as flatfooted as saying that the U.S. Constitution got slavery wrong, and therefore the Constitution is wrong. I take the Constitution to be a good document, and part of its goodness is the way in which it allows us to grow in our understanding. As Thomas Aquinas said, no positive human law will ever suffice for all time; we will always need to be legislators striving to codify and live what is good. We should not expect to arrive at our destination under our own steam; but we must try. As the Talmud says, "It is not your job to finish the work but you are not free to walk away from it."** There is still interpretive work to be done.

When I was younger, I took the Bible to be saying that women should not hold positions of ecclesiastical authority. As I have grown older, I've learned more about the cultures in which those texts were written, and it seems to me that quite the opposite conclusion could be drawn. In Genesis 3 God tells the woman, "Your desire will be for your husband, and he will rule over you." But this is in the midst of a curse, not a blessing. The text that precedes it tells us that both man and woman were made in God's image, and that they walked the same ground as God. This is the intention, the blazed trail. Somehow we have walked in another direction, and that's what Genesis 3 describes: the horizontal relationships have been turned on end, and just as God has become hidden to us, so equality has eluded us. Now we know the task is to seek God; surely, then, our task is to seek to restore all of those broken relationships, to practice tikkun olam, the healing of the world.

The Book of Job illustrates this same principle regarding women: in the beginning, before he sees God, Job's daughters have no property. After he sees God's face, Job gives his daughters an inheritance equal to their brothers'. In John's Gospel, Jesus obeys a woman, his mother, in performing his first miracle. Who is the first missionary Jesus sends out? It is a woman, and one rejected by her society because of her sin. Who first announces the Resurrection? Women.

Even stodgy old St Paul acknowledges he was taught by a woman. And some of those passages of his that have been used to justify inequality strike me as taken very seriously out of context. The famous line in The Epistle to the Ephesians, "Wives, submit to your husbands," comes in the context of a long passage about everybody submitting to everyone else, and is followed by a very long passage about husbands acting as their wives' humblest servants. And that line where St Paul says to Timothy "I do not permit a woman to speak in church...women must learn in quietness and full submission" is directed to a culture where boys went to school and girls did not. The boys already knew how to learn "in quietness and full submission" to the one reading the text. It looks to me like St Paul is saying "tell the women that their education matters every bit as much as the men's education; don't let them miss out on this opportunity just because their culture has told them they are inferior. Their culture is wrong."

I could be wrong about all this, but I'd rather be wrong on the side of giving people too much credit, too many opportunities, and too many rights, than on the side of giving others too little. If I have to stand before God and apologize for what I believe (as I imagine I will) I'd rather apologize for having too much love and too much trust than not enough. Was I wrong for receiving the Eucharist from a woman priest? I'm sorry, but I trusted God was able to deliver the sacrament through all sorts and kinds of unworthy vessels. After all, as Paul writes elsewhere, in Christ there is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, but all are one in Christ. The old distinctions that seemed to matter so much? Once we, like Job, see the face of God, we might see that we are all made in God's image, regardless of outward appearances.

Which brings me to my conclusion. Last week, a young woman in my community wrote a stirring blog post about marriage. I don't think I know enough to say very much that is wise about this matter other than what I've already said. The story of marriage in the scriptures is, it seems to me, a story that comes to us in pieces that need to be fitted together carefully, by a community. Marriage, after all, is not just about the marriage partners, but about the community that endorses, acknowledges, and protects it. In my church, at least, when two people are married, they act as priest to one another in making their vows - making this a unique sacrament - but this is usually done in the presence of a gathered community that then promises to honor and support their union. The "pieces" of marriage found in the pages of the Bible include polygamy, forcibly taking war brides, marriages of political convenience (e.g. Solomon), marriages predicated on economic necessity (e.g. Ruth), arranged marriages, marriages of love. And even divorce and remarriage - though the Bible often has particular vitriol for divorce and for the "hardness of heart" that may sometimes cause it. We don't get a rule; we get a trajectory.

That "first missionary" I mentioned? You can find her story in the fourth chapter of John's Gospel. She had been married five times, and was living with another man when Jesus met her. As far as John tells us, Jesus didn't rebuke her for this, or command her to live differently. Instead, he just let her know that he knew about her, and he continued to speak to her - something no one else in her town would do, apparently. (Even Jesus's partially enlightened disciples were astonished to find him speaking to such a woman.) He let her know he knew her, and for her, this was revelation enough. She returned to her town and told her townspeople that she was known by the Messiah. This was her Gospel.

And what a Gospel it must have been to her, that she was willing to go into the town that rejected her and tell everyone she met, everyone who hated her, that there was Good News. You may hate me, but I am known, and I am loved. Go hear for yourselves.

As I said, I'm no Biblical scholar, and I'm swimming in deep waters here. But what if we saw the stories in the Bible as offering not a simple rule but pieces of a puzzle, arrows pointing in the direction of knowing and loving one another? I'm not arguing that same-sex marriages would be free from sin; I am arguing quite the opposite, in fact, because I imagine that probably every marriage of every sort (including those that aren't called marriages) is full of unkindness and the other fruits of sin. So the task before us is, once again, to love one another, and to try to be holy.

Perhaps, rather than trying to shape laws, the church should be trying to speak a word of grace, one spoken with our lives more than anything: be holy. As you know holiness--as you are known by Holiness--work to embody it in your deepest loves. When we focus on trying to shape laws, it makes it seem that laws and power are what we most love. When our focus is on singing the joyful song of those who have chosen to try to be holy because they believe they are known by their Maker, we cannot be mistaken for people who are trying to control others. We become people who are captivated by the beauty of holiness and grace.

Again, I might be wrong, but might it not be that the whole creation is groaning to hear such a word as this? You are known. Be holy.

* Dan Savage made this claim last year; I don't think he's altogether wrong in his conclusions, and I think he's trying to do a lot of good, but he and I have different approaches to scripture, and his strikes me as hasty and dismissive. This is unfortunate, because there are few texts like the Bible when it comes to power to transform societal beliefs; and because attacking the Bible doesn't help win over those who believe it. If you don't like the popular interpretation of a text, attacking the text is not as helpful as offering a serious, scholarly rival interpretation.

** Pirke Avot 2:21

When it comes to the Bible, we've all been shaped by it, and we all have ways of responding to the pressures it has exerted while shaping us.

The early creeds try to maintain considerable latitude for how we regard the scriptures. For instance, the Nicene Creed says "We believe in the Holy Spirit...who has spoken through the prophets." Just how has the Spirit spoken, and what are we to make of that?

I'm grateful for those early Christians who, like St. Augustine, acknowledged that the scripture may have several senses. The Spirit does not speak in monotone, but in harmony, and the scriptures may sing several parts at once.

I was born into a churchgoing family, but we didn't spend much time talking about scripture. As a teenager I joined an independent church with charismatic and evangelical theology, and it was there that some of my strongest impressions of scripture were formed, in the presence of people who believed that the Spirit's voice in scripture could still be heard timelessly. While I've since grown away from that church, the idea that God speaks through scripture has stuck with me.

So not only has it shaped my life indirectly, I have sought to make myself open to it, to let it teach and guide me. Its songs and poems comfort me in hard times, and give me words when I want to express my joy and gratitude. The prophets help me to name the compass-points toward which my heart stretches. Its narratives offer opportunities for reflection on lives lived well, and poorly. And while I've made no attempt to keep all of its commandments, I find in them rules and principles that help me to live a life of "long obedience," to borrow a phrase from Nietzsche.

They give me doctrines, too, ideas about the world that make sense to me and that I don't think I could have formulated on my own. Creation, fall, and redemption; nurturing love, sin, and grace. I doubt I could explain any of these in perfectly clear and agreeable terms, but even in their vague forms (perhaps especially in their vague forms) they help me to make sense of the world.

But there is more. I take the Bible to be not just a collection of books, but a collection that holds together. The Tower of Babel in Genesis and the Tongues of Fire in Acts go together just as the Garden of Eden, the Garden of Gethsemane, and the tree-lined streets of the New Jerusalem go together. The stories of fathers and sons from Adam to Abraham, from David to Joseph, all fit together like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle; no two are alike, but taken as a whole, a larger picture forms.

This, I believe, is why the work of studying scripture matters to the communities that claim to be people of those scriptures. Putting together the puzzle is the work of our lives together.

Which is not to say that I think God is a cruel puzzle-maker. To say that would be already to have sorted out the puzzle. I'm not fond of jigsaw puzzles--when I was younger I couldn't understand why I would purchase and subject myself to an unnecessary problem. Why not just buy the picture before it's cut up? But there is real joy in playfully and willingly choosing to tackle a problem together.

So here is my small contribution to our work together: I don't think the scriptures are simply about rules and doctrines. Let's assume that God inspired the Bible; if so, and if God only wanted to deliver doctrines, God is not a very good writer. There's a lot of fluff in there that doesn't contribute directly to our list of rules.

If, on the other hand, God wanted to create a community of love and wisdom, I'm not sure there's a better way than by giving stories and poems, and by getting personally involved in that community, sharing its joys and its sorrows and its work. And if God wanted to make people who would not just obey but grow up into love and wisdom, all the more so.

This is why I take the Bible to be giving us a set of narratives that hang together, forming not a complete story but a story that is like a set of signposts, or a finger pointing in the direction we should travel. We are not static automata, nor should we strive to be. We are pilgrims with progress yet to be made. As in the myth of Pygmalion and Galatea, a loving maker wants a lover, not a lifeless statue.

More than once I've heard facile criticisms* of the Bible saying, in effect, the Bible got slavery wrong, therefore the Bible is wrong. But this is as flatfooted as saying that the U.S. Constitution got slavery wrong, and therefore the Constitution is wrong. I take the Constitution to be a good document, and part of its goodness is the way in which it allows us to grow in our understanding. As Thomas Aquinas said, no positive human law will ever suffice for all time; we will always need to be legislators striving to codify and live what is good. We should not expect to arrive at our destination under our own steam; but we must try. As the Talmud says, "It is not your job to finish the work but you are not free to walk away from it."** There is still interpretive work to be done.

When I was younger, I took the Bible to be saying that women should not hold positions of ecclesiastical authority. As I have grown older, I've learned more about the cultures in which those texts were written, and it seems to me that quite the opposite conclusion could be drawn. In Genesis 3 God tells the woman, "Your desire will be for your husband, and he will rule over you." But this is in the midst of a curse, not a blessing. The text that precedes it tells us that both man and woman were made in God's image, and that they walked the same ground as God. This is the intention, the blazed trail. Somehow we have walked in another direction, and that's what Genesis 3 describes: the horizontal relationships have been turned on end, and just as God has become hidden to us, so equality has eluded us. Now we know the task is to seek God; surely, then, our task is to seek to restore all of those broken relationships, to practice tikkun olam, the healing of the world.

The Book of Job illustrates this same principle regarding women: in the beginning, before he sees God, Job's daughters have no property. After he sees God's face, Job gives his daughters an inheritance equal to their brothers'. In John's Gospel, Jesus obeys a woman, his mother, in performing his first miracle. Who is the first missionary Jesus sends out? It is a woman, and one rejected by her society because of her sin. Who first announces the Resurrection? Women.

Even stodgy old St Paul acknowledges he was taught by a woman. And some of those passages of his that have been used to justify inequality strike me as taken very seriously out of context. The famous line in The Epistle to the Ephesians, "Wives, submit to your husbands," comes in the context of a long passage about everybody submitting to everyone else, and is followed by a very long passage about husbands acting as their wives' humblest servants. And that line where St Paul says to Timothy "I do not permit a woman to speak in church...women must learn in quietness and full submission" is directed to a culture where boys went to school and girls did not. The boys already knew how to learn "in quietness and full submission" to the one reading the text. It looks to me like St Paul is saying "tell the women that their education matters every bit as much as the men's education; don't let them miss out on this opportunity just because their culture has told them they are inferior. Their culture is wrong."

I could be wrong about all this, but I'd rather be wrong on the side of giving people too much credit, too many opportunities, and too many rights, than on the side of giving others too little. If I have to stand before God and apologize for what I believe (as I imagine I will) I'd rather apologize for having too much love and too much trust than not enough. Was I wrong for receiving the Eucharist from a woman priest? I'm sorry, but I trusted God was able to deliver the sacrament through all sorts and kinds of unworthy vessels. After all, as Paul writes elsewhere, in Christ there is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, but all are one in Christ. The old distinctions that seemed to matter so much? Once we, like Job, see the face of God, we might see that we are all made in God's image, regardless of outward appearances.

Which brings me to my conclusion. Last week, a young woman in my community wrote a stirring blog post about marriage. I don't think I know enough to say very much that is wise about this matter other than what I've already said. The story of marriage in the scriptures is, it seems to me, a story that comes to us in pieces that need to be fitted together carefully, by a community. Marriage, after all, is not just about the marriage partners, but about the community that endorses, acknowledges, and protects it. In my church, at least, when two people are married, they act as priest to one another in making their vows - making this a unique sacrament - but this is usually done in the presence of a gathered community that then promises to honor and support their union. The "pieces" of marriage found in the pages of the Bible include polygamy, forcibly taking war brides, marriages of political convenience (e.g. Solomon), marriages predicated on economic necessity (e.g. Ruth), arranged marriages, marriages of love. And even divorce and remarriage - though the Bible often has particular vitriol for divorce and for the "hardness of heart" that may sometimes cause it. We don't get a rule; we get a trajectory.

That "first missionary" I mentioned? You can find her story in the fourth chapter of John's Gospel. She had been married five times, and was living with another man when Jesus met her. As far as John tells us, Jesus didn't rebuke her for this, or command her to live differently. Instead, he just let her know that he knew about her, and he continued to speak to her - something no one else in her town would do, apparently. (Even Jesus's partially enlightened disciples were astonished to find him speaking to such a woman.) He let her know he knew her, and for her, this was revelation enough. She returned to her town and told her townspeople that she was known by the Messiah. This was her Gospel.

And what a Gospel it must have been to her, that she was willing to go into the town that rejected her and tell everyone she met, everyone who hated her, that there was Good News. You may hate me, but I am known, and I am loved. Go hear for yourselves.

As I said, I'm no Biblical scholar, and I'm swimming in deep waters here. But what if we saw the stories in the Bible as offering not a simple rule but pieces of a puzzle, arrows pointing in the direction of knowing and loving one another? I'm not arguing that same-sex marriages would be free from sin; I am arguing quite the opposite, in fact, because I imagine that probably every marriage of every sort (including those that aren't called marriages) is full of unkindness and the other fruits of sin. So the task before us is, once again, to love one another, and to try to be holy.

Perhaps, rather than trying to shape laws, the church should be trying to speak a word of grace, one spoken with our lives more than anything: be holy. As you know holiness--as you are known by Holiness--work to embody it in your deepest loves. When we focus on trying to shape laws, it makes it seem that laws and power are what we most love. When our focus is on singing the joyful song of those who have chosen to try to be holy because they believe they are known by their Maker, we cannot be mistaken for people who are trying to control others. We become people who are captivated by the beauty of holiness and grace.

Again, I might be wrong, but might it not be that the whole creation is groaning to hear such a word as this? You are known. Be holy.

*****

* Dan Savage made this claim last year; I don't think he's altogether wrong in his conclusions, and I think he's trying to do a lot of good, but he and I have different approaches to scripture, and his strikes me as hasty and dismissive. This is unfortunate, because there are few texts like the Bible when it comes to power to transform societal beliefs; and because attacking the Bible doesn't help win over those who believe it. If you don't like the popular interpretation of a text, attacking the text is not as helpful as offering a serious, scholarly rival interpretation.

** Pirke Avot 2:21

∞

Hid In My Heart

Before my friend's father died, he had a stroke that left him mostly without words for a few weeks. His near-total aphasia left little intact, but there were some words that came out readily. My friend's dad had been a pastor, and when his faculty of speech left him, the words of his prayers, of the scriptures, and of the hymns and psalms were all that remained. Daily habit of repetition had ingrained them in his heart, too deep to be erased by the stroke.

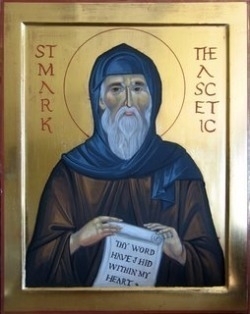

On his blog, Kelly Dean Jolley has an icon of St Mark the Ascetic, or St Mark the Wrestler, that Jolley has kindly allowed me to include here. In his hands St Mark holds a scroll that reads "Thy word have I hid within my heart." Those words are from the 119th Psalm, a long poem about scripture.

When I was in college, my French professor Charles Nunley required me to memorize a new poem every week. Every week or two I'd go to his office and he would name one of the poems I'd learned and expect me to recite it, and then to discuss it. I'm not a great memorizer, so it was painful work, but I've been grateful for the discipline every year since then. It is a gift to have verses hidden in my heart.

When I was in college, my French professor Charles Nunley required me to memorize a new poem every week. Every week or two I'd go to his office and he would name one of the poems I'd learned and expect me to recite it, and then to discuss it. I'm not a great memorizer, so it was painful work, but I've been grateful for the discipline every year since then. It is a gift to have verses hidden in my heart.

I am reminded of Mary, the mother of Jesus, when she heard what the shepherds were saying. Luke tells us that she "treasured these things in her heart," which I take to mean that she heard them, and then put them in that front room of her memory, the palm and fingertips of the mind where we touch and explore and consider ideas, turning them over and over again.

Well, this is what I do with treasured verses, anyway. Like I said, I'm a poor memorizer. But when I work at it, I hold the verses at mind's-eye level and gaze at them, running my inner eye down the length of them repeatedly, considering the way the grain moves and feeling the heft of the words until the grooves of my mind fit the notches of the words like a key. Because I hope that what I have hid in my heart will be like the Brothers Grimm's "Golden Key," which opens...well, I had better not tell you. Read it for yourself.

I wonder - when the great grinding erasure of time scrubs away at my memories, what will be left? What grooves in my grain will be too deep to scrape away? What treasures, what verses, what songs of my species will be buried too deep in my heart for the thief of time to steal?

On his blog, Kelly Dean Jolley has an icon of St Mark the Ascetic, or St Mark the Wrestler, that Jolley has kindly allowed me to include here. In his hands St Mark holds a scroll that reads "Thy word have I hid within my heart." Those words are from the 119th Psalm, a long poem about scripture.

When I was in college, my French professor Charles Nunley required me to memorize a new poem every week. Every week or two I'd go to his office and he would name one of the poems I'd learned and expect me to recite it, and then to discuss it. I'm not a great memorizer, so it was painful work, but I've been grateful for the discipline every year since then. It is a gift to have verses hidden in my heart.

When I was in college, my French professor Charles Nunley required me to memorize a new poem every week. Every week or two I'd go to his office and he would name one of the poems I'd learned and expect me to recite it, and then to discuss it. I'm not a great memorizer, so it was painful work, but I've been grateful for the discipline every year since then. It is a gift to have verses hidden in my heart.I am reminded of Mary, the mother of Jesus, when she heard what the shepherds were saying. Luke tells us that she "treasured these things in her heart," which I take to mean that she heard them, and then put them in that front room of her memory, the palm and fingertips of the mind where we touch and explore and consider ideas, turning them over and over again.

Well, this is what I do with treasured verses, anyway. Like I said, I'm a poor memorizer. But when I work at it, I hold the verses at mind's-eye level and gaze at them, running my inner eye down the length of them repeatedly, considering the way the grain moves and feeling the heft of the words until the grooves of my mind fit the notches of the words like a key. Because I hope that what I have hid in my heart will be like the Brothers Grimm's "Golden Key," which opens...well, I had better not tell you. Read it for yourself.

I wonder - when the great grinding erasure of time scrubs away at my memories, what will be left? What grooves in my grain will be too deep to scrape away? What treasures, what verses, what songs of my species will be buried too deep in my heart for the thief of time to steal?

∞

Secular Liturgy

Last night I attended the Maundy Thursday service at our church. I admit I'm not a fan of sitting still, of pews in general, or of listening to sermons. I also haven't got any great love for singing with a small congregation that doesn't really like to sing.

But I've found I need liturgy in my life. Liturgies help me mark seasons. More than that, liturgies create seasons. That's what I really need, because the creation of seasons becomes, for me, a discipline of memory.

Liturgies help me to count my days, which in turn helps me to make my days count.

I used to chafe at the remembrance of birthdays. Why should one day count more than any other? And why should one day seem more a holiday than another?

I'm slowly getting it. There is nothing special about the day; what is special is the use of the day. Cheerless debunkers never tire of pointing out to me that western Christmas is celebrated on a Roman holiday, that Easter is *really* some kind of fertility rite because it's celebrated in the springtime, that all my holidays don't mean what I think they mean because someone once celebrated them in another way. As though the genealogy of the holiday should be its only meaning, as though the celebrations of the past should have magical power over me, as though I had no power to make the days mean something new to me.

And it is true: holidays and liturgies do have power. As I have said before, what we cherish in our hearts we worship, and what we worship we come to resemble or imitate. Holidays are always about remembering, and remembering is cherishing. Of course, we don't all cherish the same things. Memorial Day is, for some, a remembrance of valor and sacrifice. For others, it is a good day for a picnic with family. Both are forms of cherishing, though the thing cherished is quite different.

Much of the difference probably comes from mindfulness and intention, or lack of intention. Everyone cherishes something, but not all of us think about what we cherish. Liturgies help me to cherish mindfully.

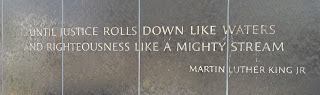

Which is why every April 4th I read or listen to Dr. King's "I Have A Dream" speech, and weep at his loss. And why every July 4th I read the Declaration of Independence. I have set aside days in my year, every year, to read texts like these, texts that have shaped my community. Because these texts aren't done with their shaping. Texts don't hit us once and do all their work; texts seep into us, their words become our words.

Reading and re-reading and reading aloud in communities - these things are like the pouring of water through leaves or grounds - the reading percolates through the words and picks up the essential oils, the savor, the color and taste of the text, and delivers it to us like tea or hot coffee. We taste the words and then the words enter our guts, our veins, our souls.

I recently read an interview with a woman who said "I don't need to go to church to believe those things," referring to her church's beliefs. True. Just as I don't need to go to the gym to get exercise, or to believe that exercise is good for me. But if I don't make a habit of getting exercise, I find I tend not to get what my body needs. The urgent matters in life so easily overwhelm the important ones. Often, when I return from the gym, my wife asks me "How was the gym?" I always think, "It was hard. Everything I do at the gym is difficult." But it is worth doing, because it helps me to maintain my health, and to fight my own decline, to fight the slow slipping away of what I want to hold onto as long as I can. If I do this for my body, why should I not also do it for my heart and mind?

I'm not writing this to endorse all liturgies. I'm confident that there are liturgies that celebrate awful things, and that there are participants in liturgies who make poor use of the liturgies they sit through. As with most of what I write here, I'm trying to sort out what I believe, and why -- as another kind of discipline, one of remembering, and of being mindful of what I believe.

The liturgy of Maundy Thursday is not an easy one, because it reminds me of two things I am capable of: I am capable, like Jesus, of washing others' feet, and of living a life of love; and I am capable, like Jesus' friends, of betraying those people and ideals I most claim to cherish and worship. If my worship is only worship in words, I find it easy to forget to worship what is best with my body, with my life. Liturgies - and we all have liturgies - are the ways I remind my whole person to stop and remember what my words claim so easily to believe.

But I've found I need liturgy in my life. Liturgies help me mark seasons. More than that, liturgies create seasons. That's what I really need, because the creation of seasons becomes, for me, a discipline of memory.

Liturgies help me to count my days, which in turn helps me to make my days count.

I used to chafe at the remembrance of birthdays. Why should one day count more than any other? And why should one day seem more a holiday than another?

I'm slowly getting it. There is nothing special about the day; what is special is the use of the day. Cheerless debunkers never tire of pointing out to me that western Christmas is celebrated on a Roman holiday, that Easter is *really* some kind of fertility rite because it's celebrated in the springtime, that all my holidays don't mean what I think they mean because someone once celebrated them in another way. As though the genealogy of the holiday should be its only meaning, as though the celebrations of the past should have magical power over me, as though I had no power to make the days mean something new to me.

And it is true: holidays and liturgies do have power. As I have said before, what we cherish in our hearts we worship, and what we worship we come to resemble or imitate. Holidays are always about remembering, and remembering is cherishing. Of course, we don't all cherish the same things. Memorial Day is, for some, a remembrance of valor and sacrifice. For others, it is a good day for a picnic with family. Both are forms of cherishing, though the thing cherished is quite different.

Much of the difference probably comes from mindfulness and intention, or lack of intention. Everyone cherishes something, but not all of us think about what we cherish. Liturgies help me to cherish mindfully.

Which is why every April 4th I read or listen to Dr. King's "I Have A Dream" speech, and weep at his loss. And why every July 4th I read the Declaration of Independence. I have set aside days in my year, every year, to read texts like these, texts that have shaped my community. Because these texts aren't done with their shaping. Texts don't hit us once and do all their work; texts seep into us, their words become our words.

Reading and re-reading and reading aloud in communities - these things are like the pouring of water through leaves or grounds - the reading percolates through the words and picks up the essential oils, the savor, the color and taste of the text, and delivers it to us like tea or hot coffee. We taste the words and then the words enter our guts, our veins, our souls.

I recently read an interview with a woman who said "I don't need to go to church to believe those things," referring to her church's beliefs. True. Just as I don't need to go to the gym to get exercise, or to believe that exercise is good for me. But if I don't make a habit of getting exercise, I find I tend not to get what my body needs. The urgent matters in life so easily overwhelm the important ones. Often, when I return from the gym, my wife asks me "How was the gym?" I always think, "It was hard. Everything I do at the gym is difficult." But it is worth doing, because it helps me to maintain my health, and to fight my own decline, to fight the slow slipping away of what I want to hold onto as long as I can. If I do this for my body, why should I not also do it for my heart and mind?

|

| The words percolate through us, and enter our veins. |

I'm not writing this to endorse all liturgies. I'm confident that there are liturgies that celebrate awful things, and that there are participants in liturgies who make poor use of the liturgies they sit through. As with most of what I write here, I'm trying to sort out what I believe, and why -- as another kind of discipline, one of remembering, and of being mindful of what I believe.

The liturgy of Maundy Thursday is not an easy one, because it reminds me of two things I am capable of: I am capable, like Jesus, of washing others' feet, and of living a life of love; and I am capable, like Jesus' friends, of betraying those people and ideals I most claim to cherish and worship. If my worship is only worship in words, I find it easy to forget to worship what is best with my body, with my life. Liturgies - and we all have liturgies - are the ways I remind my whole person to stop and remember what my words claim so easily to believe.

∞

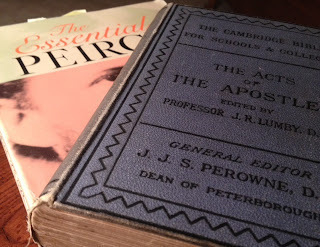

Pragmatist Scripture: Peirce and The Book of Acts

A few months ago a friend who is interested in both scripture and philosophy asked me which scripture mattered most to Charles Peirce. One obvious answer would be the writings of John, the gospeller of agape love, since agape plays such a great role in Peirce's philosophy.

The Book of Acts has recently come to mind as another strong candidate, for several reasons. I plan to write about all this in more detail soon, but I'll use this space to jot down my thinking quickly, in order to make it available to anyone who might be interested, in the Peircean spirit of shared inquiry.

The Greek title of the Book of Acts is Praxeis Apostolon, or the Deeds of the Apostles. We guess that the author of the text was the same as the author of the Gospel attributed to Luke. The title might well have been added after the book was in circulation for a while, but that's probably inconsequential. It occurred to me recently that this text begins with reminding us that the author wrote a previous book about "the things Jesus began to do and to teach," and then it narrates, without further introduction, the things that the first Christians did after Jesus' death and resurrection.

In other words, it is a book of acts, of deeds. It is a book of narratives about what people did.

Which is to say that it is not primarily a book of prayers, or of songs, or of doctrines. It tells a story, without much attempt to interpret that story. And it is the story of a community learning to work together, and learning how it must adjust its doctrines in light of the community's expansion across and into cultures, and in light of the surprising things they find the new community is empowered to accomplish.

This is appealing to Pragmatists like Peirce, who are more concerned with the way decisions lead to actions than with fixing metaphysical doctrines and whose notions of truth, ethics, and metaphysics are more experimental and transactional than systematic and permanent. Pragmatists are given to the idea that it is good for communities to work with tentative, revisable and fallible tenets, ever striving to improve their practices as the community grows.

*****

Peirce is not exactly easy to read, which helps to explain why most of what he wrote remains unpublished even a century after his death. Nevertheless, the patient reader of Peirce is often rewarded by a writer who took words very seriously.

Some of the words he used to great effect in his lectures and essays are derived from the Book of Acts. Among these phrases are a phrase he uses in his 1907 essay "A Neglected Argument For The Reality Of God," and one that comes at the end of his Cambridge Conference Lectures of 1898. The phrases are "scientific singleness of heart," and "things live and move and have their being in a logic of events." See Acts 2.46 and 17.28 for the sources of these two phrases. (The first one might also have come to Peirce through the Anglican Book of Common Prayer, as I have argued elsewhere.)

Two such phrases are not enough to make the case that Peirce was dependent on the Book of Acts, but thankfully that's not the case I'm trying to make. Peirce was well read and he cited other portions of scripture and, of course, many other books, after all. I only want to suggest that Peirce might have found the Book of Acts to be a scripture that resonates with his Pragmatism.

*****

That being said, I wish to point to one figure in the middle of the Book of Acts who might be taken to be a kind of Pragmatist saint: Epimenides.

I won't belabor that point here, as I have already written about it elsewhere. I'll only add that Epimenides appears to be the unnamed source that St Paul appeals to and cites in Acts 17.28.

The Book of Acts has recently come to mind as another strong candidate, for several reasons. I plan to write about all this in more detail soon, but I'll use this space to jot down my thinking quickly, in order to make it available to anyone who might be interested, in the Peircean spirit of shared inquiry.

The Greek title of the Book of Acts is Praxeis Apostolon, or the Deeds of the Apostles. We guess that the author of the text was the same as the author of the Gospel attributed to Luke. The title might well have been added after the book was in circulation for a while, but that's probably inconsequential. It occurred to me recently that this text begins with reminding us that the author wrote a previous book about "the things Jesus began to do and to teach," and then it narrates, without further introduction, the things that the first Christians did after Jesus' death and resurrection.

In other words, it is a book of acts, of deeds. It is a book of narratives about what people did.

Which is to say that it is not primarily a book of prayers, or of songs, or of doctrines. It tells a story, without much attempt to interpret that story. And it is the story of a community learning to work together, and learning how it must adjust its doctrines in light of the community's expansion across and into cultures, and in light of the surprising things they find the new community is empowered to accomplish.

This is appealing to Pragmatists like Peirce, who are more concerned with the way decisions lead to actions than with fixing metaphysical doctrines and whose notions of truth, ethics, and metaphysics are more experimental and transactional than systematic and permanent. Pragmatists are given to the idea that it is good for communities to work with tentative, revisable and fallible tenets, ever striving to improve their practices as the community grows.

*****

Peirce is not exactly easy to read, which helps to explain why most of what he wrote remains unpublished even a century after his death. Nevertheless, the patient reader of Peirce is often rewarded by a writer who took words very seriously.

Some of the words he used to great effect in his lectures and essays are derived from the Book of Acts. Among these phrases are a phrase he uses in his 1907 essay "A Neglected Argument For The Reality Of God," and one that comes at the end of his Cambridge Conference Lectures of 1898. The phrases are "scientific singleness of heart," and "things live and move and have their being in a logic of events." See Acts 2.46 and 17.28 for the sources of these two phrases. (The first one might also have come to Peirce through the Anglican Book of Common Prayer, as I have argued elsewhere.)

Two such phrases are not enough to make the case that Peirce was dependent on the Book of Acts, but thankfully that's not the case I'm trying to make. Peirce was well read and he cited other portions of scripture and, of course, many other books, after all. I only want to suggest that Peirce might have found the Book of Acts to be a scripture that resonates with his Pragmatism.

*****

That being said, I wish to point to one figure in the middle of the Book of Acts who might be taken to be a kind of Pragmatist saint: Epimenides.

I won't belabor that point here, as I have already written about it elsewhere. I'll only add that Epimenides appears to be the unnamed source that St Paul appeals to and cites in Acts 17.28.