selah

∞

Babel, in Paraphrase

Recently I have been wandering my city with a camera and sketchbook, looking at the ways our use and design of spaces speak about what we value.

Seeing often requires unhasty attention, or training, or both. I can't claim to have training in architecture, but I am trained in semiotics, and I suppose some of my grandfather's years as a toolmaker and my father's career as an engineer have rubbed off on me. Whatever the cause, I care about design.

The ancient story of the Tower of Babel (found in the eleventh chapter of the Book of Genesis) is also a story about design, and semiotics.

It's also a story worth unhasty attention. One hasty version goes roughly like this: everyone on earth shared a common language and common vocabulary. The people, moving to a new place, decided to build a tower to heaven, so they baked bricks and began to build. But they did not finish it; their language became many languages, and they spread out in many directions, divided from one another.

The Bible has a number of stories like this, short tales that seem to be making some simple and clear point. But as we ponder them unhastily - which is what theologians often do - we become more aware of how little we know. The obvious becomes the obscure, and the quotidien becomes mysterious.

A simple story becomes an invitation to slow down even more, and to consider. Selah, it says to us.

At first blush, the story of Babel appears to be a story of human hubris, and of God frustrating that hubris. It could be a simple parallel to the expulsion from Eden, or to the flooding of the earth in the story of Noah: there are limits, and if you transgress those limits, you will make your lot in life worse.

Lately, as I've slowed down my reading, I've been noticing something else: the bricks. The Bible does not often talk about the ethics of technology. There are passages that speak of things like the ethics of weaving, of sharing resources, and of the production, preparation, and distribution of food. But there are not many passages that name a particular human invention in the context of ethics. One of those inventions is named in several places: bricks.

The passage in Genesis 11 talks about bricks as a substitute for stone. When I was young I often worked as a stonemason and bricklayer. That experience may be what draws me to this passage. Bricks are easy to make, and easy to cut. We can standardize them, which makes building walls much faster.

The downside of bricks is related to their upside: they're easy to break, or to cut, or to erode. They don't last as long as stone, and if they're not well-reinforced, they are not as resilient against natural disasters. Some ancient stonemasons figured out how to cut and lay stones that can be jostled by an earthquake and then settle back into position, but bricks often collapse when the ground shakes beneath them. Bricks are easy to use, but they are not as reliable as stone. In comparison to many kinds of stone, bricks are a short-term investment.

This makes me wonder: what was the problem with the Tower of Babel? Was it the fact that the people were trying to build a tower to heaven? Or was it that they were trying to build one badly, or cheaply, or fast? Was it a problem of hubris, or a problem of materials and design? Genesis 11 does not answer that question directly. It leaves it as an open question for us.

Which is just what we should expect, if Genesis 11 conveys any truth. Think about this: how would this story have been told before the Tower of Babel was built? If the story is right, then before the Tower was built, the story would have been told in a language everyone would understand. But now that we have tried to build it (whatever that means) the story must be told in words that are confused, for people who are scattered and divided and who do not share vocabulary.

To paraphrase this: somehow, our use of bricks resulted in making it harder to connect with one another. And it's not clear how.

But somehow, it is a story that hundreds of generations have found worth repeating, even if our words fail to say with precision why that is so.

Maybe, just maybe, it has something to do with the way we continue to build walls of bricks. And what those bricks say about us, and what we value.

Since writing this, I started reading Christopher Alexander's book, The Timeless Way of Building, recommended to me by some friends in Sioux Falls. This line in particular stands out as serendipitous:

Seeing often requires unhasty attention, or training, or both. I can't claim to have training in architecture, but I am trained in semiotics, and I suppose some of my grandfather's years as a toolmaker and my father's career as an engineer have rubbed off on me. Whatever the cause, I care about design.

The ancient story of the Tower of Babel (found in the eleventh chapter of the Book of Genesis) is also a story about design, and semiotics.

It's also a story worth unhasty attention. One hasty version goes roughly like this: everyone on earth shared a common language and common vocabulary. The people, moving to a new place, decided to build a tower to heaven, so they baked bricks and began to build. But they did not finish it; their language became many languages, and they spread out in many directions, divided from one another.

The Bible has a number of stories like this, short tales that seem to be making some simple and clear point. But as we ponder them unhastily - which is what theologians often do - we become more aware of how little we know. The obvious becomes the obscure, and the quotidien becomes mysterious.

A simple story becomes an invitation to slow down even more, and to consider. Selah, it says to us.

At first blush, the story of Babel appears to be a story of human hubris, and of God frustrating that hubris. It could be a simple parallel to the expulsion from Eden, or to the flooding of the earth in the story of Noah: there are limits, and if you transgress those limits, you will make your lot in life worse.

The passage in Genesis 11 talks about bricks as a substitute for stone. When I was young I often worked as a stonemason and bricklayer. That experience may be what draws me to this passage. Bricks are easy to make, and easy to cut. We can standardize them, which makes building walls much faster.

The downside of bricks is related to their upside: they're easy to break, or to cut, or to erode. They don't last as long as stone, and if they're not well-reinforced, they are not as resilient against natural disasters. Some ancient stonemasons figured out how to cut and lay stones that can be jostled by an earthquake and then settle back into position, but bricks often collapse when the ground shakes beneath them. Bricks are easy to use, but they are not as reliable as stone. In comparison to many kinds of stone, bricks are a short-term investment.

*****

This makes me wonder: what was the problem with the Tower of Babel? Was it the fact that the people were trying to build a tower to heaven? Or was it that they were trying to build one badly, or cheaply, or fast? Was it a problem of hubris, or a problem of materials and design? Genesis 11 does not answer that question directly. It leaves it as an open question for us.

Which is just what we should expect, if Genesis 11 conveys any truth. Think about this: how would this story have been told before the Tower of Babel was built? If the story is right, then before the Tower was built, the story would have been told in a language everyone would understand. But now that we have tried to build it (whatever that means) the story must be told in words that are confused, for people who are scattered and divided and who do not share vocabulary.

To paraphrase this: somehow, our use of bricks resulted in making it harder to connect with one another. And it's not clear how.

But somehow, it is a story that hundreds of generations have found worth repeating, even if our words fail to say with precision why that is so.

Maybe, just maybe, it has something to do with the way we continue to build walls of bricks. And what those bricks say about us, and what we value.

*****

Update:Since writing this, I started reading Christopher Alexander's book, The Timeless Way of Building, recommended to me by some friends in Sioux Falls. This line in particular stands out as serendipitous:

"But in our time the languages have broken down. Since they are no longer shared, the processes which keep them deep have broken down: and it is therefore virtually impossible for anybody, in our time, to make a building live." (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979) p. 225

∞

Drawing Outside The Lines: Marginalia and E-Books

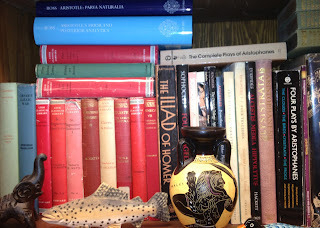

I was an early adopter of the Kindle, but I stopped using it several years ago. The books I most wanted weren't (and many still aren't) available for it, and it was hard to use it as I like to use books.

You see, I am an annotator. I draw in books.

Everyone told me when I was a kid that you should NOT draw in books. But I can't help it.

Last summer my sister-in-law, seeing me read with a pencil in my hand, asked me if I always do that. I hadn't really thought about it as unusual until then, but yes, I guess I do. That way my reading becomes a kind of conversation with the book. The author writes, and I write back.

It is becoming a bit easier to annotate e-books, but we have a long way to go, perhaps because we have structured our computers to think in a linear fashion. Computers think in stoichedon, in lines and ranks, like soldiers in formation. Which is a good way to organize information, but it's not the only way, because it's not the only way lines can move. "Idea mapping" or "mind mapping" is another way. This can be expanded to three dimensions or more, as well. Think of a way a line can move and you have another way of taking notes.

Over the years I have devised my own shorthand for note-taking. For some things, I borrow old conventions of abbreviation and expand them, like this:

And so on. Some words, like selah, have entered my annotative vocabulary because they say so much so briefly. (See footnote 3 here, about "selah.")

At times, I've also found it helpful to invent new symbols, pictograms of whole ideas, sentences that can be written a single picture. I can do these with a flick of the pen, but they're much harder to incorporate into a digital text.

I draw lines from one page to the next to connect ideas. I circle names when they first appear in a text so that I can find them again. I draw vertical lines beside paragraphs to quickly highlight long sections of text. A double line emphasizes that highlighting.

I draw maps, and sketch pictures. Sometimes I write in other languages, other alphabets, when those other languages get the idea down more quickly, or more carefully. I haven't written music in books, but I don't see why you couldn't.

And all of that becomes an icon of a conversation. The annotated page is no longer text; it is an image, and a symbol of a set of relations between ideas and authors.

When I was in grad school, José Vericat (who did not know me from Adam) kindly gave me a list of books belonging to Charles Peirce and housed in one of Harvard's libraries. Peirce died in 1914, but his lines and words still illuminate his reading of those pages.

Another bit of scholarly generosity was shown to me a few years ago when I was working on my book on the environmental vision of C.S. Lewis at the Wade Center. The director, Christopher Mitchell, learned of my interest in Lewis's reading of Henri Bergson. Mitchell brought me Lewis's copy of Bergson's Évolution Créatrice to peruse. Every page is covered with marginalia written by Lewis as he recovered from his war injuries.

I think my favorite part of Thomas Cahill's book, How The Irish Saved Civilization, was seeing the facsimiles of marginal paintings - including some racy self-portraits - by monks who copied books in Ireland in the middle ages.

My point in this long blog post? Keep drawing in books. And maybe I'll get another Kindle someday if they can figure out a way to make it easy for me to draw outside the lines. And to preserve those drawings for posterity.

You see, I am an annotator. I draw in books.

Everyone told me when I was a kid that you should NOT draw in books. But I can't help it.

Last summer my sister-in-law, seeing me read with a pencil in my hand, asked me if I always do that. I hadn't really thought about it as unusual until then, but yes, I guess I do. That way my reading becomes a kind of conversation with the book. The author writes, and I write back.

It is becoming a bit easier to annotate e-books, but we have a long way to go, perhaps because we have structured our computers to think in a linear fashion. Computers think in stoichedon, in lines and ranks, like soldiers in formation. Which is a good way to organize information, but it's not the only way, because it's not the only way lines can move. "Idea mapping" or "mind mapping" is another way. This can be expanded to three dimensions or more, as well. Think of a way a line can move and you have another way of taking notes.

Over the years I have devised my own shorthand for note-taking. For some things, I borrow old conventions of abbreviation and expand them, like this:

could - cd

would - wd

should - shd

something - s/t

everything - e/t

nothing - n/t

because - b/c

nevertheless - n/t/l

And so on. Some words, like selah, have entered my annotative vocabulary because they say so much so briefly. (See footnote 3 here, about "selah.")

At times, I've also found it helpful to invent new symbols, pictograms of whole ideas, sentences that can be written a single picture. I can do these with a flick of the pen, but they're much harder to incorporate into a digital text.

I draw lines from one page to the next to connect ideas. I circle names when they first appear in a text so that I can find them again. I draw vertical lines beside paragraphs to quickly highlight long sections of text. A double line emphasizes that highlighting.

I draw maps, and sketch pictures. Sometimes I write in other languages, other alphabets, when those other languages get the idea down more quickly, or more carefully. I haven't written music in books, but I don't see why you couldn't.

And all of that becomes an icon of a conversation. The annotated page is no longer text; it is an image, and a symbol of a set of relations between ideas and authors.

When I was in grad school, José Vericat (who did not know me from Adam) kindly gave me a list of books belonging to Charles Peirce and housed in one of Harvard's libraries. Peirce died in 1914, but his lines and words still illuminate his reading of those pages.

Another bit of scholarly generosity was shown to me a few years ago when I was working on my book on the environmental vision of C.S. Lewis at the Wade Center. The director, Christopher Mitchell, learned of my interest in Lewis's reading of Henri Bergson. Mitchell brought me Lewis's copy of Bergson's Évolution Créatrice to peruse. Every page is covered with marginalia written by Lewis as he recovered from his war injuries.

I think my favorite part of Thomas Cahill's book, How The Irish Saved Civilization, was seeing the facsimiles of marginal paintings - including some racy self-portraits - by monks who copied books in Ireland in the middle ages.

My point in this long blog post? Keep drawing in books. And maybe I'll get another Kindle someday if they can figure out a way to make it easy for me to draw outside the lines. And to preserve those drawings for posterity.

∞

Great Books, Pedagogy, and Hope

Great Books and the Great Conversation

About fifteen years ago I enrolled in the "Great Books" M.A. program at St John's College in Santa Fe, New Mexico. It was one of the best decisions I've ever made.

Much as I appreciate my undergraduate education, too often it rewarded me for concealing my ignorance and emphasizing what I already knew. The problem, of course, is that my ignorance was thus shielded from the sterilizing sunlight of others' scrutiny and instruction.

Confessing Our Ignorance

Matthew Davis, my tutor and advisor at St John's, won me over to another way of viewing literature when, on one of the first days we met, he pointed to a passage in Plato's Republic and said "I have always wondered what Plato means by that." Looking up at the class, he asked, "Do any of you have any ideas about what he might be trying to say?"

Mr. Davis is the first professor I recall who openly confessed his ignorance, and who thereby modeled what it means to open oneself to the instruction of a great text. Not much has shaped my academic life as much as that.

Grappling With Classic Texts

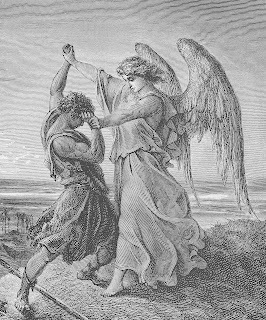

As I have begun to mature into my own place as a teacher, I often think that this is the best thing I can give my students: not professorial and authoritative descriptions of texts, but an example of what it means to be a student. I can try to be an example of someone who sits with texts and listens to them, grappling with them, like Jacob with the angel or like Menelaus with Proteus: persistently grappling with my superior and refusing to let go until I receive a blessing. (Selah.)

For the last few years I have been seeking out and reading classic novels. As I read them I feel like an apprentice architect touring buildings, looking not just at the outward form and function but looking for the supporting structure, trying to notice the decisions the artist made about what to include and what to omit.

Along the way, I have begun trying to write bits of dialogue, scenes, characters, and other elements of fiction. I'm not trying to write a novel so much as trying to perform experiments the way high school science students do in labs: not to discover something new but to learn haptically, kinesthetically, experientially what the masters already know. I can't say that I've learned to write novels, so don't expect anything from me there. But as I've paid attention, I feel I've begun to squeeze some blessings out of the books, including some unexpected ones.

I've noticed, for instance, that Craig Nova writes about the olfactory sense in a way that makes me notice aromas I never noticed before. John Steinbeck has begun to make me care more about friendship, and about the people in front of me. Harold Frederic has me rethinking my early faith, and this is helping me look ahead as I try to nurture it into a faith worth having. Novels are helping me see the world differently.

So What Does This Have To Do With Hope?

I just finished Graham Greene's The Honorary Consul. Apparently this was Greene's favorite of his own works, and I can see why. Like many of the really good novels I've read, it has left me thinking about a range of topics, and longing for someone to talk about it with.

Which brings me to hope. I started reading Greene because Bill Swart, my friend and colleague, told me about how good Greene's novels are. Bill was right about this, so I sought him out the other day to talk more about Greene. We said too much to cover it all here, but Bill said something I can't bear not to repeat. When we began discussing Greene's The Power and the Glory, Bill said "That book gave me hope that my own self-perception might be wrong."

If you know the novel, you know why, because you know how Greene's characters wrestle with being both sinners and saints. If you don't know the novel, let me recommend it to you.

We Should Keep Teaching And Reading Fiction

I still have a lot to learn about novels. I doubt I'll ever write one - or a good one, anyway. But I'm delighting in reading them. Perhaps that's why they matter so much: they delight us, and capture us. When I'm in a good book I feel like I'm really in it. I stop seeing words on a page and start seeing, with some inner eye, the world the novelist sees.

And like all my other travels, journeys into fiction leave me a different person. I see different possibilities, I see -- and smell -- my world differently. I know it's important to teach young people to read non-fiction, but teaching fiction might be for them what The Power and the Glory was for Bill: a tonic for his soul, a sweet drink of hope that didn't just entertain, but that allowed him to envision his life, his work, and his purpose in an entirely new way.

About fifteen years ago I enrolled in the "Great Books" M.A. program at St John's College in Santa Fe, New Mexico. It was one of the best decisions I've ever made.

Much as I appreciate my undergraduate education, too often it rewarded me for concealing my ignorance and emphasizing what I already knew. The problem, of course, is that my ignorance was thus shielded from the sterilizing sunlight of others' scrutiny and instruction.

Confessing Our Ignorance

Matthew Davis, my tutor and advisor at St John's, won me over to another way of viewing literature when, on one of the first days we met, he pointed to a passage in Plato's Republic and said "I have always wondered what Plato means by that." Looking up at the class, he asked, "Do any of you have any ideas about what he might be trying to say?"

Mr. Davis is the first professor I recall who openly confessed his ignorance, and who thereby modeled what it means to open oneself to the instruction of a great text. Not much has shaped my academic life as much as that.

Grappling With Classic Texts

As I have begun to mature into my own place as a teacher, I often think that this is the best thing I can give my students: not professorial and authoritative descriptions of texts, but an example of what it means to be a student. I can try to be an example of someone who sits with texts and listens to them, grappling with them, like Jacob with the angel or like Menelaus with Proteus: persistently grappling with my superior and refusing to let go until I receive a blessing. (Selah.)

For the last few years I have been seeking out and reading classic novels. As I read them I feel like an apprentice architect touring buildings, looking not just at the outward form and function but looking for the supporting structure, trying to notice the decisions the artist made about what to include and what to omit.

Along the way, I have begun trying to write bits of dialogue, scenes, characters, and other elements of fiction. I'm not trying to write a novel so much as trying to perform experiments the way high school science students do in labs: not to discover something new but to learn haptically, kinesthetically, experientially what the masters already know. I can't say that I've learned to write novels, so don't expect anything from me there. But as I've paid attention, I feel I've begun to squeeze some blessings out of the books, including some unexpected ones.

I've noticed, for instance, that Craig Nova writes about the olfactory sense in a way that makes me notice aromas I never noticed before. John Steinbeck has begun to make me care more about friendship, and about the people in front of me. Harold Frederic has me rethinking my early faith, and this is helping me look ahead as I try to nurture it into a faith worth having. Novels are helping me see the world differently.

So What Does This Have To Do With Hope?

I just finished Graham Greene's The Honorary Consul. Apparently this was Greene's favorite of his own works, and I can see why. Like many of the really good novels I've read, it has left me thinking about a range of topics, and longing for someone to talk about it with.

Which brings me to hope. I started reading Greene because Bill Swart, my friend and colleague, told me about how good Greene's novels are. Bill was right about this, so I sought him out the other day to talk more about Greene. We said too much to cover it all here, but Bill said something I can't bear not to repeat. When we began discussing Greene's The Power and the Glory, Bill said "That book gave me hope that my own self-perception might be wrong."

If you know the novel, you know why, because you know how Greene's characters wrestle with being both sinners and saints. If you don't know the novel, let me recommend it to you.

We Should Keep Teaching And Reading Fiction

I still have a lot to learn about novels. I doubt I'll ever write one - or a good one, anyway. But I'm delighting in reading them. Perhaps that's why they matter so much: they delight us, and capture us. When I'm in a good book I feel like I'm really in it. I stop seeing words on a page and start seeing, with some inner eye, the world the novelist sees.

And like all my other travels, journeys into fiction leave me a different person. I see different possibilities, I see -- and smell -- my world differently. I know it's important to teach young people to read non-fiction, but teaching fiction might be for them what The Power and the Glory was for Bill: a tonic for his soul, a sweet drink of hope that didn't just entertain, but that allowed him to envision his life, his work, and his purpose in an entirely new way.