spanish

∞

Gracias, señora Orza

Estimada Sra. Orza,

One day when I was in middle school in New York you said to me “You’re good at languages. You should go to Middlebury.” I hadn’t heard of it before, and I had been planning to attend the cheapest local college I could attend, to save my family the cost of college. Then you handed me a brochure from Middlebury, about their summer language programs. A year later, when I was leaving to work in Nepal for the summer, you gave me a blank journal as a parting gift, reminding me that writing matters.

I haven’t seen you since then, and I haven’t been able to track you down to thank you in person, so I’m firing this out into the internet to say thank you to you and to all the other teachers like you. Why? Because you changed my life.

Three years after I last saw you, I drove to Middlebury to check it out, and I fell in love with the place. I sat in on a Religion class (a subject I thought I wouldn't find interesting at all) and learned more about religion in that single hour than I thought possible.

So I applied, and I got in, with a scholarship. I guess they thought I should go there, too! Over the next four years that college made it possible for me to study in Spain; to learn to read and translate multiple forms of classical Greek; to be exposed to history as more than names and dates; to study physics, and math, philosophy, and even a little more religion.

Looking back on those years now, I see that my whole career has arisen out of classes I took there.

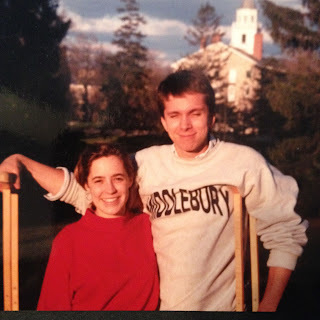

And best of all, I met this amazing woman! I think you’d like her. Like you, she’s smart and sweet. Like you, she encourages me to keep learning. And like you, she’s fluent in Spanish.

Far more than the classes, she has changed my life. So often it's the people you meet--and not just the things you learn--that change you. I'm grateful to have met you both.

So thanks for being a Spanish teacher in a middle school in rural New York. Thanks for putting up with all of us kids in your classes, year after year. And thanks for taking my future seriously enough that you thought that my life, my travels, and my studies really mattered. You saw all that far more clearly than I did back then, but over the years I’ve come to see what you saw, and I’m forever grateful.

Your loving student,

Dave

One day when I was in middle school in New York you said to me “You’re good at languages. You should go to Middlebury.” I hadn’t heard of it before, and I had been planning to attend the cheapest local college I could attend, to save my family the cost of college. Then you handed me a brochure from Middlebury, about their summer language programs. A year later, when I was leaving to work in Nepal for the summer, you gave me a blank journal as a parting gift, reminding me that writing matters.

I haven’t seen you since then, and I haven’t been able to track you down to thank you in person, so I’m firing this out into the internet to say thank you to you and to all the other teachers like you. Why? Because you changed my life.

Three years after I last saw you, I drove to Middlebury to check it out, and I fell in love with the place. I sat in on a Religion class (a subject I thought I wouldn't find interesting at all) and learned more about religion in that single hour than I thought possible.

So I applied, and I got in, with a scholarship. I guess they thought I should go there, too! Over the next four years that college made it possible for me to study in Spain; to learn to read and translate multiple forms of classical Greek; to be exposed to history as more than names and dates; to study physics, and math, philosophy, and even a little more religion.

Looking back on those years now, I see that my whole career has arisen out of classes I took there.

And best of all, I met this amazing woman! I think you’d like her. Like you, she’s smart and sweet. Like you, she encourages me to keep learning. And like you, she’s fluent in Spanish.

|

| We started dating in college, and we're still dating each other now, even though we're both married. I think you'd like her. |

Far more than the classes, she has changed my life. So often it's the people you meet--and not just the things you learn--that change you. I'm grateful to have met you both.

So thanks for being a Spanish teacher in a middle school in rural New York. Thanks for putting up with all of us kids in your classes, year after year. And thanks for taking my future seriously enough that you thought that my life, my travels, and my studies really mattered. You saw all that far more clearly than I did back then, but over the years I’ve come to see what you saw, and I’m forever grateful.

Your loving student,

Dave

∞

and it's also a short trip to Tikal:

They also have a school for teaching indigenous Mayan languages like Itzá, Quiché, and Kekchí.

There are some slightly cheaper language schools in Guatemala, but this one makes your money go a long way, since they use the income to preserve and protect one of the largest unbroken stretches of rainforest North of the Amazon, and to preserve indigenous culture, protect archaeological sites, and promote sustainable agriculture. In addition to learning Spanish, you can learn about medicinal plants; local cooking, music, and culture; rainforest ecology; Mayan archaeology (they have a licensed archaeologist on their staff); and a lot more. Students interested in rural medicine can ask about arranging to work in the local medical clinic. Worth every penny.

(Thanks to Luke Lynass and the other Augustana College students who worked to get this new website up and running.)

New Bio-Itzá Website!

Check it out.

The Asociación Bio Itzá does great, inexpensive Spanish-language immersion programs for individuals or groups in Petén, Guatemala. It’s a short trip from the Flores airport to their school and homestays in San José:

and it's also a short trip to Tikal:

They also have a school for teaching indigenous Mayan languages like Itzá, Quiché, and Kekchí.

There are some slightly cheaper language schools in Guatemala, but this one makes your money go a long way, since they use the income to preserve and protect one of the largest unbroken stretches of rainforest North of the Amazon, and to preserve indigenous culture, protect archaeological sites, and promote sustainable agriculture. In addition to learning Spanish, you can learn about medicinal plants; local cooking, music, and culture; rainforest ecology; Mayan archaeology (they have a licensed archaeologist on their staff); and a lot more. Students interested in rural medicine can ask about arranging to work in the local medical clinic. Worth every penny.

(Thanks to Luke Lynass and the other Augustana College students who worked to get this new website up and running.)

∞

Learn Spanish in Guatemala, Help Save the Rainforest

Immersive Spanish language learning in Guatemala’s Asociación Bio-Itzá supports cultural preservation and sustainable community development efforts.