St Paul

- Forgive Onesimus, the indentured servant who ran away, breaking his contract with Philemon;

- Forgive Onesimus for stealing from Philemon as he fled;

- Welcome Onesimus back, not as a slave but as a family member.

∞

Reason For Hope

Nearly every spring term I teach a class called “Theology and Philosophy in Dialogue.” I inherited the title and the course description when I started teaching at my current school in 2005. Each year the course changes a little, in response to my students and what I perceive to be relevant themes in our world and culture.

Apologetics and Postmodernism

When I first taught it, I made it a class about apologetics and postmodernism. By “apologetics” I mean the work of giving a reasoned account of one’s commitments; by “postmodernism,” I mean the suspicion that what look like reasoned accounts might have unexamined depths and layers to them. In the context of theism—and in particular Christian theism—apologetics has a long history that reaches back to the early years of Christianity. Saint Peter wrote in his longer letter that Christians should always be prepared to give a reasoned defense of the hope they bore within them. That phrase “reasoned defense” is a translation of the Greek word apologia, which can mean a legal defense, and from which we get our word “apologetics.”

When Saint Paul of Tarsus found himself in Athens, speaking to Stoic and Epicurean philosophers on the Areopagus, he tried to explain his beliefs not in the terms of his culture but in theirs. He doesn’t seem to have won many over to his views that day, but if nothing else was accomplished, at the end of the conversation it was clearer where Paul and the Greek philosophers were in agreement and where they disagreed. If immediate conversion was the aim of his speech, it wasn’t a great speech. But if he aimed to build a bridge of mutual understanding, I’d say he was pretty successful.

One of the keys to his success, I think, was familiarity with the culture around him. I’ve written about this elsewhere, so I won’t belabor it here, but I’ll just point out that Paul quoted two Greek philosophical poets, Epimenides and Aratos, and he did so in a culturally appropriate and significant place, since several centuries before Paul’s travels, Epimenides (who was from Crete) also traveled to Athens and also spoke on the Areopagus about the gods and salvation.

Understanding Atheism(s)

A few years after I started teaching that course, I shifted the course to take seriously the “New Atheists.” I figured that if my religious students graduated without hearing the strongest challenges to their faith, I, as a professor who teaches theology, was letting them down. I wanted them to know that soon they’d hear strong arguments against their religious heritage, beliefs, and practices, and that these arguments should be taken seriously. For my Christian students, I framed this as a way of living the commandment to love God with one’s mind.

Of course, only some of my students are religious, and some of the religious students aren’t Christians. (I’m at a Lutheran university in a small Midwestern city, so until recently most of them were at least culturally Christian; that’s changing quickly, though.) I wanted this to be a class that was helpful for everyone, so I started to turn this into a class about mutual understanding. I now teach my students how to distinguish between a dozen different kinds of (and reasons for) atheism, lest they make the mistake of oversimplifying the complexity of their neighbors and of themselves.

Understanding and Agapic Love

Arguments about religion can quickly become unkind. Many of us have been wounded in the name of religion, and those wounds heal slowly, if at all. How could we make this into a class that was—on its surface, and in its content—about theology and philosophy, while really making it about something like mutual care?

I just mentioned that great commandment: Love God with your heart, soul, mind, and strength, Jesus said, echoing Moses. Then he added a second commandment: love your neighbor as yourself. Everything else hangs on these two commandments, he said.

Explaining those two commandments would be almost as hard as trying to keep them, so I won’t try to do so here. I’ll just point out that it’s fascinating to command someone to love someone else; that the love that’s called for here is agapic love, i.e. the love that seeks the good and flourishing of the beloved; and that the commandments are so lacking in specificity as to call for both extensive commentary and continued practice. They’re vague commandments, which means they require us to work them out in community, over time. And in all likelihood we’ll never get them right. That may seem like a weakness, but it also strikes me as offering the freedom to try and to fail and to help one another to try again.

Anxiety, Ultimate Concerns, and Societal “Stress Fractures”

Which brings me to the most recent incarnation of my Theology and Philosophy in Dialogue class. Over the last few years it seems to me that my students have become more anxious about their economic futures, more stressed about exams and jobs, more focused on education and work as competition for rank. I could be wrong, but as the stress and anxiety have grown, it seems like my students are so busy jockeying for position that they have a hard time putting the cause of their stress into words. On top of all this, here in the United States, it feels like we’ve been using stronger words so that we can give voice to our anxiety more quickly. We aren’t broken, but we’ve got lots of hairline stress fractures that are too small to see. We aren’t bleeding, but we’ve got a constant dull ache.

In other words, it seems like we’re fearful without being able to identify the object of our fear, and that has us prepared to see enemies wherever we look. This does not make it easy to love our neighbors as ourselves (unless we also have that kind of distrust of ourselves, which is a real possibility, I suppose.) And at least in the way Paul Tillich described God: whatever we regard as our ultimate concern functions as our God. When economic anxiety, jostling for rank, or fear of losing one’s place in the future, (these are all ways of saying the same thing, I think) take on the role of “ultimate concern” in our lives, they become our gods.

The course I’m teaching this semester still has traces of every previous semester’s influences. We talk a little about apologetics, and that’s a helpful way of teaching students about logic, inference, probability, and certainty. (Ask some of them about “doxastic certainty” or my “haystack problem” and you’ll see what I mean.)

And we still talk about postmodernism, though as my career has shifted from the philosophy of religion to environmental philosophy, ethics, and policy, I’m inclined to follow Scott Russell Sanders’ view (see note, below) that if we spend too much time theorizing and not enough time caring for the world we share, incredulity towards metanarratives can quickly become a new metanarrative that we fail to examine sufficiently.

And we still talk about atheisms. This semester I have sketched a dozen forms of atheism once again, and we’re now working our way through them.

Friendship, and “Best Construction”

But the aim of the class, more than anything, is friendship.

I told all the students that this was the case on the first day of class.

And here, I think, is where Theology and Philosophy can have a really helpful dialogue in our time. I teach at a Lutheran university, so it’s fitting to invoke Luther. In his Small Catechism, he offers some commentary on the Ten Commandments. His commentary on the eighth commandment is helpful. The commandment reads simply, like this:

This is hard.

“A Mutual, Joint-Stock World, In All Meridians”

It’s especially hard when we feel that others are getting ahead of us, and that we are in a competition with everyone else. If the world is a zero-sum game, then everyone run, and the Devil take the hindmost. But what if Queequeg is right? When Queequeg sees a fellow sailor drowning and no one moves to save the sailor, Queequeg leaps into the water to save his fellow. There is no question of whether they are of the same tribe, the same party, the same race, the same team. Queequeg is, as far as anyone aboard the ship knows, a cannibal. And yet the narrator, observing Queequeg’s agapic care for his fellow sailor, offers this comment:

It’s much easier to approach theological conversations with the idea that our theology is a weapon and that our enemies are those with whom we disagree. It’s so easy to forget what Saint Paul wrote, that we don’t fight against flesh and blood, but against far less tangible, invisible forces that would have us view our neighbors with malice.

Could we approach theology the way Queequeg approaches the plight of his fellow sailor? Is it possible to maintain one’s cherished beliefs while recognizing that one’s object of “ultimate concern” might be something we don’t yet see with certainty and clarity? I cannot speak for others, so I’ll just offer this confession: I’m aware of a capacity in myself to care more for my theology than for the God that my theology claims to describe. In simpler terms: my own theology can become so dear to me that it becomes an idol, displacing the very God I set out to love and serve. And how to I love and serve my God? So far, the best I can offer you is this: I should love God with all I am, and I should love my neighbor as myself. Does that seem unclear to you? It does to me. Which means I need all the help I can get in clarifying my vision. Right now I see in a glass, darkly.

The philosopher Jonathan Lear suggests a principle akin to Queequeg’s, and to Luther’s: the principle of humanity. He describes it like this:

Conclusion

It’s appropriate to me that I teach this course in Lent each year. Lent is a good time for self-examination, and that includes an examination of all kinds of pieties and supposed certainties. What is it that we hold to be of ultimate concern? What do we love with all our heart, soul, mind, and strength? That might just be playing the role of a god in our lives. If so, does that God help us to love our neighbors as ourselves?

I could be wrong in all I say in this class. I enter it with “fear and trembling,” knowing that there’s so much I don’t know, and knowing that many of my students might be wiser than I am. I know they might have seen the divine far more clearly than I ever will in this life.

But oh, how I want them to live well, not to be entangled by anxious grief, not to be afraid of the future, not to be burdened by relentless suspicions and fears.

Yes, there are other subjects I could teach, and yes, there are other jobs I could do. But for me, right now, this one feels like a good way to reexamine my own ultimate concerns, and a good way to help others to do the same. May I do so without malice, with agapic love, and with the constant practice of putting the best construction on everything.

Amen. Lord, have mercy.

*****

Notes:

* Scott Russell Sanders: I'm thinking of his essay, "The Warehouse and the Wilderness," and in particular the opening pages of that essay. You can find it in A Conservationist Manifesto, beginning on page 71. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009)

* Ulpian's words are cited in Justinian, Institutes, Book 1, Title 1, Sec. 3.

* Lear has an endnote at the end of this sentence. It reads: “This principle is also known as the ‘principle of charity,’ and the most famous arguments for it are given by Donald Davidson. See his “Radical Interpretation,” in Inquiries Into Truth And Interpretation (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984), pp. 136-137; “Belief and the Basis of Meaning,” ibid., pp. 152-153; “Thought and Talk,” ibid., pp. 168-169; “On the Very Idea of a Conceptual Scheme,” ibid., pp. 196-197; “The Method of Truth in Metaphysics,” ibid., pp. 200-201.”

Apologetics and Postmodernism

When I first taught it, I made it a class about apologetics and postmodernism. By “apologetics” I mean the work of giving a reasoned account of one’s commitments; by “postmodernism,” I mean the suspicion that what look like reasoned accounts might have unexamined depths and layers to them. In the context of theism—and in particular Christian theism—apologetics has a long history that reaches back to the early years of Christianity. Saint Peter wrote in his longer letter that Christians should always be prepared to give a reasoned defense of the hope they bore within them. That phrase “reasoned defense” is a translation of the Greek word apologia, which can mean a legal defense, and from which we get our word “apologetics.”

When Saint Paul of Tarsus found himself in Athens, speaking to Stoic and Epicurean philosophers on the Areopagus, he tried to explain his beliefs not in the terms of his culture but in theirs. He doesn’t seem to have won many over to his views that day, but if nothing else was accomplished, at the end of the conversation it was clearer where Paul and the Greek philosophers were in agreement and where they disagreed. If immediate conversion was the aim of his speech, it wasn’t a great speech. But if he aimed to build a bridge of mutual understanding, I’d say he was pretty successful.

One of the keys to his success, I think, was familiarity with the culture around him. I’ve written about this elsewhere, so I won’t belabor it here, but I’ll just point out that Paul quoted two Greek philosophical poets, Epimenides and Aratos, and he did so in a culturally appropriate and significant place, since several centuries before Paul’s travels, Epimenides (who was from Crete) also traveled to Athens and also spoke on the Areopagus about the gods and salvation.

Understanding Atheism(s)

A few years after I started teaching that course, I shifted the course to take seriously the “New Atheists.” I figured that if my religious students graduated without hearing the strongest challenges to their faith, I, as a professor who teaches theology, was letting them down. I wanted them to know that soon they’d hear strong arguments against their religious heritage, beliefs, and practices, and that these arguments should be taken seriously. For my Christian students, I framed this as a way of living the commandment to love God with one’s mind.

Of course, only some of my students are religious, and some of the religious students aren’t Christians. (I’m at a Lutheran university in a small Midwestern city, so until recently most of them were at least culturally Christian; that’s changing quickly, though.) I wanted this to be a class that was helpful for everyone, so I started to turn this into a class about mutual understanding. I now teach my students how to distinguish between a dozen different kinds of (and reasons for) atheism, lest they make the mistake of oversimplifying the complexity of their neighbors and of themselves.

Understanding and Agapic Love

Arguments about religion can quickly become unkind. Many of us have been wounded in the name of religion, and those wounds heal slowly, if at all. How could we make this into a class that was—on its surface, and in its content—about theology and philosophy, while really making it about something like mutual care?

I just mentioned that great commandment: Love God with your heart, soul, mind, and strength, Jesus said, echoing Moses. Then he added a second commandment: love your neighbor as yourself. Everything else hangs on these two commandments, he said.

Explaining those two commandments would be almost as hard as trying to keep them, so I won’t try to do so here. I’ll just point out that it’s fascinating to command someone to love someone else; that the love that’s called for here is agapic love, i.e. the love that seeks the good and flourishing of the beloved; and that the commandments are so lacking in specificity as to call for both extensive commentary and continued practice. They’re vague commandments, which means they require us to work them out in community, over time. And in all likelihood we’ll never get them right. That may seem like a weakness, but it also strikes me as offering the freedom to try and to fail and to help one another to try again.

Anxiety, Ultimate Concerns, and Societal “Stress Fractures”

Which brings me to the most recent incarnation of my Theology and Philosophy in Dialogue class. Over the last few years it seems to me that my students have become more anxious about their economic futures, more stressed about exams and jobs, more focused on education and work as competition for rank. I could be wrong, but as the stress and anxiety have grown, it seems like my students are so busy jockeying for position that they have a hard time putting the cause of their stress into words. On top of all this, here in the United States, it feels like we’ve been using stronger words so that we can give voice to our anxiety more quickly. We aren’t broken, but we’ve got lots of hairline stress fractures that are too small to see. We aren’t bleeding, but we’ve got a constant dull ache.

In other words, it seems like we’re fearful without being able to identify the object of our fear, and that has us prepared to see enemies wherever we look. This does not make it easy to love our neighbors as ourselves (unless we also have that kind of distrust of ourselves, which is a real possibility, I suppose.) And at least in the way Paul Tillich described God: whatever we regard as our ultimate concern functions as our God. When economic anxiety, jostling for rank, or fear of losing one’s place in the future, (these are all ways of saying the same thing, I think) take on the role of “ultimate concern” in our lives, they become our gods.

The course I’m teaching this semester still has traces of every previous semester’s influences. We talk a little about apologetics, and that’s a helpful way of teaching students about logic, inference, probability, and certainty. (Ask some of them about “doxastic certainty” or my “haystack problem” and you’ll see what I mean.)

And we still talk about postmodernism, though as my career has shifted from the philosophy of religion to environmental philosophy, ethics, and policy, I’m inclined to follow Scott Russell Sanders’ view (see note, below) that if we spend too much time theorizing and not enough time caring for the world we share, incredulity towards metanarratives can quickly become a new metanarrative that we fail to examine sufficiently.

And we still talk about atheisms. This semester I have sketched a dozen forms of atheism once again, and we’re now working our way through them.

Friendship, and “Best Construction”

But the aim of the class, more than anything, is friendship.

I told all the students that this was the case on the first day of class.

And here, I think, is where Theology and Philosophy can have a really helpful dialogue in our time. I teach at a Lutheran university, so it’s fitting to invoke Luther. In his Small Catechism, he offers some commentary on the Ten Commandments. His commentary on the eighth commandment is helpful. The commandment reads simply, like this:

“Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor.”Like the other commandments I’ve mentioned, it is only a few words long. And like those others, it leaves room for commentary. Luther’s commentary does something that I find very helpful. While the commandment is negative (“thou shalt not,” it says) Luther thought that alongside each negative commandment was something positive. So he writes:

What does this mean?--Answer. We should fear and love God that we may not deceitfully belie, betray, slander, or defame our neighbor, but defend him, [think and] speak well of him, and put the best construction on everything.”This is akin to what Plato offers in several ways in his Republic, and to Ulpian’s legal principle of “giving to each person their due,” (see note, below) but it goes a little further, with an agapic tinge: Luther doesn’t just tell us not to lie, nor does he tell us to be simply honest, but to put the best construction on everything.

This is hard.

“A Mutual, Joint-Stock World, In All Meridians”

It’s especially hard when we feel that others are getting ahead of us, and that we are in a competition with everyone else. If the world is a zero-sum game, then everyone run, and the Devil take the hindmost. But what if Queequeg is right? When Queequeg sees a fellow sailor drowning and no one moves to save the sailor, Queequeg leaps into the water to save his fellow. There is no question of whether they are of the same tribe, the same party, the same race, the same team. Queequeg is, as far as anyone aboard the ship knows, a cannibal. And yet the narrator, observing Queequeg’s agapic care for his fellow sailor, offers this comment:

Was there ever such unconsciousness? He did not seem to think that he at all deserved a medal from the Humane and Magnanimous Societies. He only asked for water—fresh water—something to wipe the brine off; that done, he put on dry clothes, lighted his pipe, and leaning against the bulwarks, and mildly eyeing those around him, seemed to be saying to himself—“It’s a mutual, joint-stock world, in all meridians. We cannibals must help these Christians.” -- Herman Melville, Moby Dick. (New York: Signet, 1980) 76

It’s much easier to approach theological conversations with the idea that our theology is a weapon and that our enemies are those with whom we disagree. It’s so easy to forget what Saint Paul wrote, that we don’t fight against flesh and blood, but against far less tangible, invisible forces that would have us view our neighbors with malice.

Could we approach theology the way Queequeg approaches the plight of his fellow sailor? Is it possible to maintain one’s cherished beliefs while recognizing that one’s object of “ultimate concern” might be something we don’t yet see with certainty and clarity? I cannot speak for others, so I’ll just offer this confession: I’m aware of a capacity in myself to care more for my theology than for the God that my theology claims to describe. In simpler terms: my own theology can become so dear to me that it becomes an idol, displacing the very God I set out to love and serve. And how to I love and serve my God? So far, the best I can offer you is this: I should love God with all I am, and I should love my neighbor as myself. Does that seem unclear to you? It does to me. Which means I need all the help I can get in clarifying my vision. Right now I see in a glass, darkly.

The philosopher Jonathan Lear suggests a principle akin to Queequeg’s, and to Luther’s: the principle of humanity. He describes it like this:

“The interpretation thus fits what philosophers call the principle of humanity: that we should try to interpret others as saying something true—guided by our own sense of what is true and of what they could reasonably believe.” -- Jonathan Lear, Radical Hope. 4 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006) (See note below)The Episcopal Church’s Book of Common Prayer offers another commentary on the fourth commandment, the commandment not to take the name of God in vain. The Book of Common Prayer rephrases the commandment like this:

You shall not invoke with malice the Name of the Lord your God.

Amen. Lord have mercy.The rephrasing is a commentary on “in vain.” Invoking God’s name in vain is equated with invoking it with malice, that is, with the opposite of agapic love.

Conclusion

It’s appropriate to me that I teach this course in Lent each year. Lent is a good time for self-examination, and that includes an examination of all kinds of pieties and supposed certainties. What is it that we hold to be of ultimate concern? What do we love with all our heart, soul, mind, and strength? That might just be playing the role of a god in our lives. If so, does that God help us to love our neighbors as ourselves?

I could be wrong in all I say in this class. I enter it with “fear and trembling,” knowing that there’s so much I don’t know, and knowing that many of my students might be wiser than I am. I know they might have seen the divine far more clearly than I ever will in this life.

But oh, how I want them to live well, not to be entangled by anxious grief, not to be afraid of the future, not to be burdened by relentless suspicions and fears.

Yes, there are other subjects I could teach, and yes, there are other jobs I could do. But for me, right now, this one feels like a good way to reexamine my own ultimate concerns, and a good way to help others to do the same. May I do so without malice, with agapic love, and with the constant practice of putting the best construction on everything.

Amen. Lord, have mercy.

*****

Notes:

* Scott Russell Sanders: I'm thinking of his essay, "The Warehouse and the Wilderness," and in particular the opening pages of that essay. You can find it in A Conservationist Manifesto, beginning on page 71. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009)

* Ulpian's words are cited in Justinian, Institutes, Book 1, Title 1, Sec. 3.

* Lear has an endnote at the end of this sentence. It reads: “This principle is also known as the ‘principle of charity,’ and the most famous arguments for it are given by Donald Davidson. See his “Radical Interpretation,” in Inquiries Into Truth And Interpretation (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984), pp. 136-137; “Belief and the Basis of Meaning,” ibid., pp. 152-153; “Thought and Talk,” ibid., pp. 168-169; “On the Very Idea of a Conceptual Scheme,” ibid., pp. 196-197; “The Method of Truth in Metaphysics,” ibid., pp. 200-201.”

∞

Of Men and of Angels

"If I speak with the tongues of men and of angels, but I have not love, then I have become a resounding gong or a clanging cymbal."

That's from one of St. Paul's letters to the church in Corinth. It's a passage often read at weddings, probably because it speaks eloquently about agapic love.

I like it for another reason: it has a nice onomatopoeic pun in the Greek text. Paul's "If I speak..." is lalo; his "clanging" is alaladzon, which sounds like the noise a gong makes and sounds like it could mean "un-speaking." (In Greek, words that begin with "a-" are often like English words beginning with "un-".)

This week, as we approach the third Sunday in Advent, I was looking again at a poem I wrote during this week a few years ago, after the school shooting in Newtown. In it I compared first responders and teachers and others who give up so much for the sake of the common good to angels. That is my second-most read post ever.

The most-read post is one I wrote after Ferguson, about the militarization of our first responders, and the way the tools we equip ourselves with change the way we interact with the world - and with other people.

Both of these posts are about public servants. Taken together they remind me that what is done in love can be heroic and life-giving, and what is done in fear can become tyrannical. They remind me that we have a tendency to revere the outward signs of badges and uniforms, when we should judge characters by the habits they embody and by the actions that show the habits.

And they remind me that we have a long, long way to go before we can say we have learned to love one another.

*****

I should add that even the title to this post is misleading. The word Paul uses is not "men" but "humans." I like the cadence of the old translation "men" but the word is anthropon, not andron. Normally I prefer the more inclusive (and more accurate) "humans" but I first learned this verse in an older, poetic translation and the rhythm of it has stuck with me.

That's from one of St. Paul's letters to the church in Corinth. It's a passage often read at weddings, probably because it speaks eloquently about agapic love.

I like it for another reason: it has a nice onomatopoeic pun in the Greek text. Paul's "If I speak..." is lalo; his "clanging" is alaladzon, which sounds like the noise a gong makes and sounds like it could mean "un-speaking." (In Greek, words that begin with "a-" are often like English words beginning with "un-".)

This week, as we approach the third Sunday in Advent, I was looking again at a poem I wrote during this week a few years ago, after the school shooting in Newtown. In it I compared first responders and teachers and others who give up so much for the sake of the common good to angels. That is my second-most read post ever.

The most-read post is one I wrote after Ferguson, about the militarization of our first responders, and the way the tools we equip ourselves with change the way we interact with the world - and with other people.

Both of these posts are about public servants. Taken together they remind me that what is done in love can be heroic and life-giving, and what is done in fear can become tyrannical. They remind me that we have a tendency to revere the outward signs of badges and uniforms, when we should judge characters by the habits they embody and by the actions that show the habits.

And they remind me that we have a long, long way to go before we can say we have learned to love one another.

*****

I should add that even the title to this post is misleading. The word Paul uses is not "men" but "humans." I like the cadence of the old translation "men" but the word is anthropon, not andron. Normally I prefer the more inclusive (and more accurate) "humans" but I first learned this verse in an older, poetic translation and the rhythm of it has stuck with me.

∞

Theodicy and Phenomenal Curiosity

I have, right now, a terrific headache. It is a long, spidery headache whose bulging, raspy abdomen sits over my eyes and whose long forelegs reach across my head and down my spine. One leg is probing my belly and provoking nausea. It came on suddenly, dropping from the air, and it has become a constant efflorescence of discomfort. Each moment it is renewed. I try to turn my attention away, and it pulses, drawing me back. Fine, I will give it my attention and stare it down, dominate it. No, it has no steady gaze to match; every instant it is a new hostility towards being. It will not hold still, it is my Proteus, but I am no Menelaus. I cannot grapple it into submission.

I should stop writing, stop looking at the screen, but I want, as Bugbee says in the first page of The Inward Morning, to "get it down," to attend to this moment as its own revelation. I want, in a way, to put this idea to the test. I can write and think when I am feeling well, but it is hard to write in times like this.

Life is interesting. This, too, is an interesting moment, and this pain is interesting.

The urge to turn this into a rule for others is to be resisted. My pain is interesting to me because I have chosen to make it so. I have chosen to be curious while I am able. And this is not the worst headache I've had, it's just strong and annoying.

But -- and this is the important thing, I think -- I must not insist that others do the same. I must not say that "pain is God's megaphone to rouse a deaf world," I must not say that "all things work together for good," that pain is all part of a bigger plan.

I admit that all of that may be true. It may be that the suffering of others will be the darkness that makes the brightness of the divine and eternal chiaroscuro shine brighter.

But to insist that pain is good is the privilege of those who are in no pain and the blasphemy of those who have forgotten fellow-feeling. It is lacking in sympathy, and in kindness. It is, in short, lacking in love.

In one of his letters to the church in Corinth, St. Paul wrote something like this: no matter what I say, no matter how beautifully I say it, if I speak without love, I might as well not be speaking at all. (I am paraphrasing, so if you're someone who's bothered by people paraphrasing the Bible and want to see his words, here you go.)

I cannot write any more right now.

*****

It is now several days later, and the pain is gone. Which means that now, when I think of the pain, I do so through the watery filter of time, which bends and distorts the image like water bending the image of the dipped oar. I no longer behold it as I did when I was in medias res, in the midst of things. I'm glad it doesn't hurt, but I've got to remember not to make it seem easier than it was.

Years ago a surgeon cut me open "from stem to stern" (his cheerful words, not mine) and then stapled me back together. I awoke barely able to breathe. The painkillers they gave me didn't remove the pain, they only relocated it to a part of my brain that cared less, made it less the center of my attention. Even there, it constantly tried to crawl back into the center, to take over my consciousness. I'm grateful that it did not last long. My awareness of that gratitude gives me great sympathy for those who cannot make their pain end, who have no hope that soon the healing will make the pain a dull memory rather than a sharp presence goading their consciousness.

At the time, I found it a helpful strategy to attend to the pain as a curiosity, to tell myself "this is interesting," and to ask "what can I learn from this pain right now?" I couldn't sustain this for long, but I could do it again and again, with ever-renewed curiosity, and I found enormous solace and spiritual interest in it. It put me above my pain, and stripped my pain of its domineering attitude. It no longer loomed over me while I gazed down at it with wondering eyes.

But again, this is extremely difficult to sustain, and it probably takes a certain weird, philosophical warp of mind to begin with, a phenomenal curiosity cultivated and strengthened by long habit well before the pain began. It's hard to come up with something like this in the moment agony strikes.

*****

The upshot of all this, for me, is twofold: first, it is good to have discovered, in the midst of my own pain, that I may always regard my own life as interesting, no matter what happens. Second, I must always remember that this is a curious discovery I have made about myself, not a universal fact for all people.

Of course, I am writing my discovery down here because I hope that it will prove true for others. And I think its greatest application is not for the destruction of sharp physical pain but for addressing the flat white pain of boredom. When boredom drops down from above and wraps us in its gauzy, nauseating silk, this, too, can become the object of our curiosity. The very fact of our boredom may be examined, and examined profitably.

But in all our examinations, we must not be - we must never be - unkind by despising the pain of others, dismissing it and insisting that if we can dismiss it, they can too.

I should stop writing, stop looking at the screen, but I want, as Bugbee says in the first page of The Inward Morning, to "get it down," to attend to this moment as its own revelation. I want, in a way, to put this idea to the test. I can write and think when I am feeling well, but it is hard to write in times like this.

Life is interesting. This, too, is an interesting moment, and this pain is interesting.

The urge to turn this into a rule for others is to be resisted. My pain is interesting to me because I have chosen to make it so. I have chosen to be curious while I am able. And this is not the worst headache I've had, it's just strong and annoying.

But -- and this is the important thing, I think -- I must not insist that others do the same. I must not say that "pain is God's megaphone to rouse a deaf world," I must not say that "all things work together for good," that pain is all part of a bigger plan.

I admit that all of that may be true. It may be that the suffering of others will be the darkness that makes the brightness of the divine and eternal chiaroscuro shine brighter.

But to insist that pain is good is the privilege of those who are in no pain and the blasphemy of those who have forgotten fellow-feeling. It is lacking in sympathy, and in kindness. It is, in short, lacking in love.

In one of his letters to the church in Corinth, St. Paul wrote something like this: no matter what I say, no matter how beautifully I say it, if I speak without love, I might as well not be speaking at all. (I am paraphrasing, so if you're someone who's bothered by people paraphrasing the Bible and want to see his words, here you go.)

I cannot write any more right now.

*****

It is now several days later, and the pain is gone. Which means that now, when I think of the pain, I do so through the watery filter of time, which bends and distorts the image like water bending the image of the dipped oar. I no longer behold it as I did when I was in medias res, in the midst of things. I'm glad it doesn't hurt, but I've got to remember not to make it seem easier than it was.

Years ago a surgeon cut me open "from stem to stern" (his cheerful words, not mine) and then stapled me back together. I awoke barely able to breathe. The painkillers they gave me didn't remove the pain, they only relocated it to a part of my brain that cared less, made it less the center of my attention. Even there, it constantly tried to crawl back into the center, to take over my consciousness. I'm grateful that it did not last long. My awareness of that gratitude gives me great sympathy for those who cannot make their pain end, who have no hope that soon the healing will make the pain a dull memory rather than a sharp presence goading their consciousness.

At the time, I found it a helpful strategy to attend to the pain as a curiosity, to tell myself "this is interesting," and to ask "what can I learn from this pain right now?" I couldn't sustain this for long, but I could do it again and again, with ever-renewed curiosity, and I found enormous solace and spiritual interest in it. It put me above my pain, and stripped my pain of its domineering attitude. It no longer loomed over me while I gazed down at it with wondering eyes.

But again, this is extremely difficult to sustain, and it probably takes a certain weird, philosophical warp of mind to begin with, a phenomenal curiosity cultivated and strengthened by long habit well before the pain began. It's hard to come up with something like this in the moment agony strikes.

*****

The upshot of all this, for me, is twofold: first, it is good to have discovered, in the midst of my own pain, that I may always regard my own life as interesting, no matter what happens. Second, I must always remember that this is a curious discovery I have made about myself, not a universal fact for all people.

Of course, I am writing my discovery down here because I hope that it will prove true for others. And I think its greatest application is not for the destruction of sharp physical pain but for addressing the flat white pain of boredom. When boredom drops down from above and wraps us in its gauzy, nauseating silk, this, too, can become the object of our curiosity. The very fact of our boredom may be examined, and examined profitably.

But in all our examinations, we must not be - we must never be - unkind by despising the pain of others, dismissing it and insisting that if we can dismiss it, they can too.

∞

One thing that made the sermon especially strong was its open-endedness: our priest didn't try to apply the sermon to any one social problem, as he could have. Instead, he invited all his listeners to consider whether we'd be willing to have big love remake our lives. In other words, rather than making this into a doctrinal roll-call or a chance to affirm that we all believe the same thing and then move on, unchanged, we were invited to consider, in quiet self-examination, whether we were willing to let love rule in our lives.

One thing that made the sermon especially strong was its open-endedness: our priest didn't try to apply the sermon to any one social problem, as he could have. Instead, he invited all his listeners to consider whether we'd be willing to have big love remake our lives. In other words, rather than making this into a doctrinal roll-call or a chance to affirm that we all believe the same thing and then move on, unchanged, we were invited to consider, in quiet self-examination, whether we were willing to let love rule in our lives.

Part of me really doesn't like church. There's so much about it that bores me, and I usually like sermons least of all. And when I'm not bored, I'm often surrounded by people I don't know very well, shaking my hand and passing a sign of peace. It's an introvert-germophobe's introduction to the doctrine of hell, I guess, so it does serve that theological purpose. I'd prefer a quick nod, some formal bowing, a lot of incense and some well-tuned bells, but you can't always get what you want.

Part of me really doesn't like church. There's so much about it that bores me, and I usually like sermons least of all. And when I'm not bored, I'm often surrounded by people I don't know very well, shaking my hand and passing a sign of peace. It's an introvert-germophobe's introduction to the doctrine of hell, I guess, so it does serve that theological purpose. I'd prefer a quick nod, some formal bowing, a lot of incense and some well-tuned bells, but you can't always get what you want.

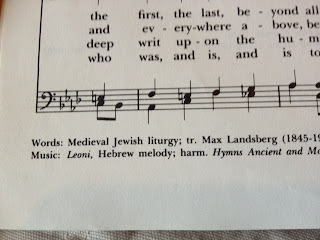

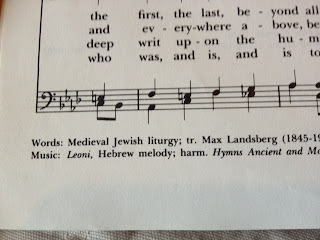

This morning was a pretty good morning. Not only did I hear that excellent sermon that will provide food for thought all week, we also sang a hymn that was translated from a Medieval Hebrew liturgy. Good hymnals and prayerbooks can be bouquets of the choicest flowers of religious poetry. The Book of Common Prayer has often rescued my anguished mind when it cannot find words. Often, when I sing hymns to the room-filling sound of a well-played pipe organ, I find myself wondering how people who do not have a congregation to sing with find opportunities to sing with others. That probably sounds judgmental, but I don't mean it to. I just wish there were more songs sung by people in our daily lives. I suspect the near-universal ownership of iPods is a result of the vanishing tradition of singing together.

This morning was a pretty good morning. Not only did I hear that excellent sermon that will provide food for thought all week, we also sang a hymn that was translated from a Medieval Hebrew liturgy. Good hymnals and prayerbooks can be bouquets of the choicest flowers of religious poetry. The Book of Common Prayer has often rescued my anguished mind when it cannot find words. Often, when I sing hymns to the room-filling sound of a well-played pipe organ, I find myself wondering how people who do not have a congregation to sing with find opportunities to sing with others. That probably sounds judgmental, but I don't mean it to. I just wish there were more songs sung by people in our daily lives. I suspect the near-universal ownership of iPods is a result of the vanishing tradition of singing together.

Can I Ask Questions In Church?

Today I heard a thoughtful, thought-provoking sermon about St Paul's Epistle to Philemon. The heart of it was this: Paul urged Philemon not to claim his legal right, but to lay aside his rights for the sake of the big love that wants to remodel his whole life.

Nobody in their right mind wants that.

Which is why Paul describes that big love elsewhere as foolishness to Greeks - and, he might have added, to anyone else who takes reason seriously.

After all, it's a little bit crazy to lay aside your legal rights for the sake of others. In Philemon's case, Paul was asking him to:

*****

One thing that made the sermon especially strong was its open-endedness: our priest didn't try to apply the sermon to any one social problem, as he could have. Instead, he invited all his listeners to consider whether we'd be willing to have big love remake our lives. In other words, rather than making this into a doctrinal roll-call or a chance to affirm that we all believe the same thing and then move on, unchanged, we were invited to consider, in quiet self-examination, whether we were willing to let love rule in our lives.

One thing that made the sermon especially strong was its open-endedness: our priest didn't try to apply the sermon to any one social problem, as he could have. Instead, he invited all his listeners to consider whether we'd be willing to have big love remake our lives. In other words, rather than making this into a doctrinal roll-call or a chance to affirm that we all believe the same thing and then move on, unchanged, we were invited to consider, in quiet self-examination, whether we were willing to let love rule in our lives.

This is like Mary's approach in John's Gospel, when she tells Jesus "They have no more wine," then tells the servants, "Do whatever he says." She knows enough to know that she doesn't know all the answers. I think our priest was saying something similar today: he doesn't know all the answers, but he's committed to big love, and was inviting us to consider whether we also share that confidence.

To put it differently, he left us with a question to mull over for the week.

Which is often far more helpful than being left with an answer.

*****

Part of me really doesn't like church. There's so much about it that bores me, and I usually like sermons least of all. And when I'm not bored, I'm often surrounded by people I don't know very well, shaking my hand and passing a sign of peace. It's an introvert-germophobe's introduction to the doctrine of hell, I guess, so it does serve that theological purpose. I'd prefer a quick nod, some formal bowing, a lot of incense and some well-tuned bells, but you can't always get what you want.

Part of me really doesn't like church. There's so much about it that bores me, and I usually like sermons least of all. And when I'm not bored, I'm often surrounded by people I don't know very well, shaking my hand and passing a sign of peace. It's an introvert-germophobe's introduction to the doctrine of hell, I guess, so it does serve that theological purpose. I'd prefer a quick nod, some formal bowing, a lot of incense and some well-tuned bells, but you can't always get what you want.

But you do often get what you need, and I think of church the way I think of prayer, or aerobic exercise, or dietary fiber: I need them. Even, and perhaps especially, when I don't want them. And when they are a part of my life, my life feels more whole.

This can be hard to explain to others, so I understand if you think I go to church because it makes me feel good, or because my culture has made it hard for me to think of doing otherwise, or because I feel guilty when I don't go.

I actually feel pretty good when I don't go to church, just like I feel pretty good when I decide to write a blog post instead of going on that four-mile run I had planned.

And so often, when I attend churches, I hear or see things I wish I hadn't heard or seen. These congregations founded on the worship of big love can become gardens overrun by the weeds of uncharitable hearts; some "hymns" I hear are schmaltzy or foolish, or unintentionally (I hope!) promote slavish and unkind ideas about race or gender. At times like that, I'm tempted to give up on "organized" religion altogether.

*****

This morning was a pretty good morning. Not only did I hear that excellent sermon that will provide food for thought all week, we also sang a hymn that was translated from a Medieval Hebrew liturgy. Good hymnals and prayerbooks can be bouquets of the choicest flowers of religious poetry. The Book of Common Prayer has often rescued my anguished mind when it cannot find words. Often, when I sing hymns to the room-filling sound of a well-played pipe organ, I find myself wondering how people who do not have a congregation to sing with find opportunities to sing with others. That probably sounds judgmental, but I don't mean it to. I just wish there were more songs sung by people in our daily lives. I suspect the near-universal ownership of iPods is a result of the vanishing tradition of singing together.

This morning was a pretty good morning. Not only did I hear that excellent sermon that will provide food for thought all week, we also sang a hymn that was translated from a Medieval Hebrew liturgy. Good hymnals and prayerbooks can be bouquets of the choicest flowers of religious poetry. The Book of Common Prayer has often rescued my anguished mind when it cannot find words. Often, when I sing hymns to the room-filling sound of a well-played pipe organ, I find myself wondering how people who do not have a congregation to sing with find opportunities to sing with others. That probably sounds judgmental, but I don't mean it to. I just wish there were more songs sung by people in our daily lives. I suspect the near-universal ownership of iPods is a result of the vanishing tradition of singing together.

When I came home I saw that a friend had tagged me in a post on Facebook, where she shared this article about the importance of continuing to ask big questions. To which I say "amen."

The article raises just this question of whether a decline in attendance at religious services decreases the places in which can we ask big questions:

The article raises just this question of whether a decline in attendance at religious services decreases the places in which can we ask big questions:

"“For anyone who goes to church, these are the questions they are essentially grappling with via their faith,” said Brooks. Indeed, a measurable drop in religious affiliation and attendance at houses of worship may be a factor in the decline of a culture of inquiry and conversation."

I don't know if that's true, and I don't want to claim that the sky is falling because the pews aren't full. But I do find that sitting in the pew helps me, and I think it could be more helpful to more people if there were more sermons like the one I heard today. It's good to ask questions together, and to let the questions do their work.

So I hope that more of us who think that meeting together to pray and sing and reflect on what we believe is a worthwhile practice will do as our priest did this morning, inviting others to turn with him to reflect on the big questions, and the big ideas, and the big love, that - in my case, at least - can keep us from living unexamined lives.

∞

Written On The Skin

One of the peculiar things about teaching Greek and knowing several other ancient languages is that people often come to me seeking help with tattoos.

A few years ago a student named Brian came to me and asked "How do you say 'Suck Less' in Greek?" Apparently this was a phrase that his running coach said to his team to inspire them to run better.

As crude as the phrase is, I was intrigued by the problem of translation. "In order to translate the phrase I'd have to know what you mean by it," I replied. I spent a little while explaining how it would be possible to say, for instance, that an infant should nurse less; or that one should inhale less strongly. Or, if you pursue the more colloquial usage of the verb "suck," you might decide that it refers to poor behavior or - ahem - to a kind of erotic pleasure-giving in which the giver is thought to be demeaned by the giving.

Eventually I made the case that if you want to say it in Classical Greek, it would make sense to say it in a way that attended to the use of words in that language, and pointed him to Plutarch's Sayings of Spartan Women as a source of pithy sayings about living and acting strenuously. Ever since I took my first Greek class with Eve Adler at Middlebury College years ago, I've liked the phrase η ταν η επι τας, (at the link above, see #16 under "Other Spartan Women"; click on the Greek flag to see the full Greek text) which is often translated "Come back with your shield or upon it," meaning "Act virtuously in battle; either die with your weapons or win with your weapons, but do not throw them away in order to win your life at the expense of your virtue." I like the Greek phrase for its Laconian pithiness.

Of course, that one didn't quite make sense for a runner, so I showed him another from the same collection, κατα βημα της αρετης μεμνησο, or "With every step, remember [your] virtue." ("Virtue" is not a perfect translation; you could translate it as "excellence" also.)

Three years have passed since that conversation with Brian, but a few months ago he tracked me down and showed me his tattoo, which I rather like:

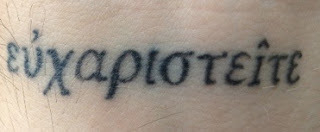

In a new twist, last year another student asked me to help him find the Greek verb "give thanks" as it appears in I Thessalonians 5.18. He didn't tell me what he planned to do with it, but when I saw him later that year at a wedding he showed me this, which he has tattooed on his wrist:

The word you see is ευχαριστειτε, related to our word "Eucharist" and the modern Greek ευχαριστω, meaning "I thank you."

I say this is a "new twist" because at least one passage in the Hebrew scriptures (Leviticus 19.28) appears to prohibit tattooing one's skin. Getting a tattoo, and in particular getting a tattoo of scripture, offers a bit of insight into one's hermeneutics. If the Gospels prohibited tattoos, I doubt many Christians would get them, but since the prohibition comes in the Hebrew scriptures, and since it seems to be tied to particular practices of worship or enslavement that no longer seem relevant, many young Christians are untroubled by it.

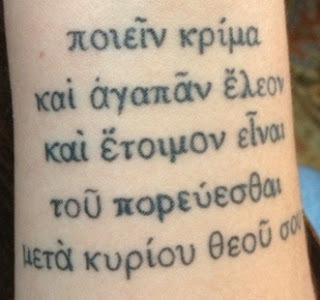

Recently one of my advisees showed me one of several tattoos she has recently acquired. This one is a longer Biblical text, from the prophet Micah, chapter 6, verse 8. I thought it interesting that she chose to get the Septuagint Greek rather than the Hebrew. She knows and translates Biblical (Koine) Greek and so I suppose she felt closer to that language. The text below means "...to do justice and to love mercy and to be ready/zealous to walk humbly with the Lord your God."

I like that verse quite a lot. If you don't know it, it begins by saying that this is what God asks of people. It's the sort of description that makes religion sound less like a burden and more like a description of a life well-lived.

I'm always reluctant to give advice about tattoos, because they're so permanent and so personal. And when I do give advice, I always want to write footnotes about regional dialects and historical and textual variants, or about the difficulties of translation. Quotes out of their native context so often seem lonely to me - such is my academic habit, of always seeing texts as living and moving and having their being* in nests and webs of other texts. Perhaps that's why I've never been inked myself, and I doubt I ever will get a "tat." I'm just not confident I've found words or an image that I'd want written on me forever. Sometimes that feels virtuous because it's prudent; other times I wonder if that's not a moral failing on my part, like I should be willing to commit to something. But I think for now I will remain uninked, and will continue to admire the commitments of my students.

* For example: I am borrowing this phrase ("live and move and have their being") from St Paul in Acts 17.28; he, in turn, appears to be borrowing it from Epimenides, who writes Εν αυτω γαρ ζωμεν και κινουμεθα και εσμεν. The phrase winds up being used in a number of other places, having been so eloquently translated into English by the King James Version of the Bible. See, for example, its use in the Book of Common Prayer, and in the first line of the hymn "We Come O Christ To Thee."

A few years ago a student named Brian came to me and asked "How do you say 'Suck Less' in Greek?" Apparently this was a phrase that his running coach said to his team to inspire them to run better.

As crude as the phrase is, I was intrigued by the problem of translation. "In order to translate the phrase I'd have to know what you mean by it," I replied. I spent a little while explaining how it would be possible to say, for instance, that an infant should nurse less; or that one should inhale less strongly. Or, if you pursue the more colloquial usage of the verb "suck," you might decide that it refers to poor behavior or - ahem - to a kind of erotic pleasure-giving in which the giver is thought to be demeaned by the giving.

Eventually I made the case that if you want to say it in Classical Greek, it would make sense to say it in a way that attended to the use of words in that language, and pointed him to Plutarch's Sayings of Spartan Women as a source of pithy sayings about living and acting strenuously. Ever since I took my first Greek class with Eve Adler at Middlebury College years ago, I've liked the phrase η ταν η επι τας, (at the link above, see #16 under "Other Spartan Women"; click on the Greek flag to see the full Greek text) which is often translated "Come back with your shield or upon it," meaning "Act virtuously in battle; either die with your weapons or win with your weapons, but do not throw them away in order to win your life at the expense of your virtue." I like the Greek phrase for its Laconian pithiness.

Of course, that one didn't quite make sense for a runner, so I showed him another from the same collection, κατα βημα της αρετης μεμνησο, or "With every step, remember [your] virtue." ("Virtue" is not a perfect translation; you could translate it as "excellence" also.)

Three years have passed since that conversation with Brian, but a few months ago he tracked me down and showed me his tattoo, which I rather like:

In a new twist, last year another student asked me to help him find the Greek verb "give thanks" as it appears in I Thessalonians 5.18. He didn't tell me what he planned to do with it, but when I saw him later that year at a wedding he showed me this, which he has tattooed on his wrist:

The word you see is ευχαριστειτε, related to our word "Eucharist" and the modern Greek ευχαριστω, meaning "I thank you."

I say this is a "new twist" because at least one passage in the Hebrew scriptures (Leviticus 19.28) appears to prohibit tattooing one's skin. Getting a tattoo, and in particular getting a tattoo of scripture, offers a bit of insight into one's hermeneutics. If the Gospels prohibited tattoos, I doubt many Christians would get them, but since the prohibition comes in the Hebrew scriptures, and since it seems to be tied to particular practices of worship or enslavement that no longer seem relevant, many young Christians are untroubled by it.

Recently one of my advisees showed me one of several tattoos she has recently acquired. This one is a longer Biblical text, from the prophet Micah, chapter 6, verse 8. I thought it interesting that she chose to get the Septuagint Greek rather than the Hebrew. She knows and translates Biblical (Koine) Greek and so I suppose she felt closer to that language. The text below means "...to do justice and to love mercy and to be ready/zealous to walk humbly with the Lord your God."

I like that verse quite a lot. If you don't know it, it begins by saying that this is what God asks of people. It's the sort of description that makes religion sound less like a burden and more like a description of a life well-lived.

I'm always reluctant to give advice about tattoos, because they're so permanent and so personal. And when I do give advice, I always want to write footnotes about regional dialects and historical and textual variants, or about the difficulties of translation. Quotes out of their native context so often seem lonely to me - such is my academic habit, of always seeing texts as living and moving and having their being* in nests and webs of other texts. Perhaps that's why I've never been inked myself, and I doubt I ever will get a "tat." I'm just not confident I've found words or an image that I'd want written on me forever. Sometimes that feels virtuous because it's prudent; other times I wonder if that's not a moral failing on my part, like I should be willing to commit to something. But I think for now I will remain uninked, and will continue to admire the commitments of my students.

*****

* For example: I am borrowing this phrase ("live and move and have their being") from St Paul in Acts 17.28; he, in turn, appears to be borrowing it from Epimenides, who writes Εν αυτω γαρ ζωμεν και κινουμεθα και εσμεν. The phrase winds up being used in a number of other places, having been so eloquently translated into English by the King James Version of the Bible. See, for example, its use in the Book of Common Prayer, and in the first line of the hymn "We Come O Christ To Thee."

*****

Update: a week or so after posting this I ran into the mother of one of the people whose tattoos are shown above. She thanked me, though I am not sure whether she was thanking me for helping her son get a tattoo, or for helping him to get the grammar right.

∞

Scripture's Trajectory: You Are Known; Be Holy

Everybody interprets texts. Interpreting texts means, among other things, determining the trajectory of the texts. Where are they coming from, and where do they point us?

When it comes to the Bible, we've all been shaped by it, and we all have ways of responding to the pressures it has exerted while shaping us.

The early creeds try to maintain considerable latitude for how we regard the scriptures. For instance, the Nicene Creed says "We believe in the Holy Spirit...who has spoken through the prophets." Just how has the Spirit spoken, and what are we to make of that?

I'm grateful for those early Christians who, like St. Augustine, acknowledged that the scripture may have several senses. The Spirit does not speak in monotone, but in harmony, and the scriptures may sing several parts at once.

I was born into a churchgoing family, but we didn't spend much time talking about scripture. As a teenager I joined an independent church with charismatic and evangelical theology, and it was there that some of my strongest impressions of scripture were formed, in the presence of people who believed that the Spirit's voice in scripture could still be heard timelessly. While I've since grown away from that church, the idea that God speaks through scripture has stuck with me.

So not only has it shaped my life indirectly, I have sought to make myself open to it, to let it teach and guide me. Its songs and poems comfort me in hard times, and give me words when I want to express my joy and gratitude. The prophets help me to name the compass-points toward which my heart stretches. Its narratives offer opportunities for reflection on lives lived well, and poorly. And while I've made no attempt to keep all of its commandments, I find in them rules and principles that help me to live a life of "long obedience," to borrow a phrase from Nietzsche.

They give me doctrines, too, ideas about the world that make sense to me and that I don't think I could have formulated on my own. Creation, fall, and redemption; nurturing love, sin, and grace. I doubt I could explain any of these in perfectly clear and agreeable terms, but even in their vague forms (perhaps especially in their vague forms) they help me to make sense of the world.

But there is more. I take the Bible to be not just a collection of books, but a collection that holds together. The Tower of Babel in Genesis and the Tongues of Fire in Acts go together just as the Garden of Eden, the Garden of Gethsemane, and the tree-lined streets of the New Jerusalem go together. The stories of fathers and sons from Adam to Abraham, from David to Joseph, all fit together like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle; no two are alike, but taken as a whole, a larger picture forms.

This, I believe, is why the work of studying scripture matters to the communities that claim to be people of those scriptures. Putting together the puzzle is the work of our lives together.

Which is not to say that I think God is a cruel puzzle-maker. To say that would be already to have sorted out the puzzle. I'm not fond of jigsaw puzzles--when I was younger I couldn't understand why I would purchase and subject myself to an unnecessary problem. Why not just buy the picture before it's cut up? But there is real joy in playfully and willingly choosing to tackle a problem together.

So here is my small contribution to our work together: I don't think the scriptures are simply about rules and doctrines. Let's assume that God inspired the Bible; if so, and if God only wanted to deliver doctrines, God is not a very good writer. There's a lot of fluff in there that doesn't contribute directly to our list of rules.

If, on the other hand, God wanted to create a community of love and wisdom, I'm not sure there's a better way than by giving stories and poems, and by getting personally involved in that community, sharing its joys and its sorrows and its work. And if God wanted to make people who would not just obey but grow up into love and wisdom, all the more so.

This is why I take the Bible to be giving us a set of narratives that hang together, forming not a complete story but a story that is like a set of signposts, or a finger pointing in the direction we should travel. We are not static automata, nor should we strive to be. We are pilgrims with progress yet to be made. As in the myth of Pygmalion and Galatea, a loving maker wants a lover, not a lifeless statue.

More than once I've heard facile criticisms* of the Bible saying, in effect, the Bible got slavery wrong, therefore the Bible is wrong. But this is as flatfooted as saying that the U.S. Constitution got slavery wrong, and therefore the Constitution is wrong. I take the Constitution to be a good document, and part of its goodness is the way in which it allows us to grow in our understanding. As Thomas Aquinas said, no positive human law will ever suffice for all time; we will always need to be legislators striving to codify and live what is good. We should not expect to arrive at our destination under our own steam; but we must try. As the Talmud says, "It is not your job to finish the work but you are not free to walk away from it."** There is still interpretive work to be done.

When I was younger, I took the Bible to be saying that women should not hold positions of ecclesiastical authority. As I have grown older, I've learned more about the cultures in which those texts were written, and it seems to me that quite the opposite conclusion could be drawn. In Genesis 3 God tells the woman, "Your desire will be for your husband, and he will rule over you." But this is in the midst of a curse, not a blessing. The text that precedes it tells us that both man and woman were made in God's image, and that they walked the same ground as God. This is the intention, the blazed trail. Somehow we have walked in another direction, and that's what Genesis 3 describes: the horizontal relationships have been turned on end, and just as God has become hidden to us, so equality has eluded us. Now we know the task is to seek God; surely, then, our task is to seek to restore all of those broken relationships, to practice tikkun olam, the healing of the world.

The Book of Job illustrates this same principle regarding women: in the beginning, before he sees God, Job's daughters have no property. After he sees God's face, Job gives his daughters an inheritance equal to their brothers'. In John's Gospel, Jesus obeys a woman, his mother, in performing his first miracle. Who is the first missionary Jesus sends out? It is a woman, and one rejected by her society because of her sin. Who first announces the Resurrection? Women.

Even stodgy old St Paul acknowledges he was taught by a woman. And some of those passages of his that have been used to justify inequality strike me as taken very seriously out of context. The famous line in The Epistle to the Ephesians, "Wives, submit to your husbands," comes in the context of a long passage about everybody submitting to everyone else, and is followed by a very long passage about husbands acting as their wives' humblest servants. And that line where St Paul says to Timothy "I do not permit a woman to speak in church...women must learn in quietness and full submission" is directed to a culture where boys went to school and girls did not. The boys already knew how to learn "in quietness and full submission" to the one reading the text. It looks to me like St Paul is saying "tell the women that their education matters every bit as much as the men's education; don't let them miss out on this opportunity just because their culture has told them they are inferior. Their culture is wrong."

I could be wrong about all this, but I'd rather be wrong on the side of giving people too much credit, too many opportunities, and too many rights, than on the side of giving others too little. If I have to stand before God and apologize for what I believe (as I imagine I will) I'd rather apologize for having too much love and too much trust than not enough. Was I wrong for receiving the Eucharist from a woman priest? I'm sorry, but I trusted God was able to deliver the sacrament through all sorts and kinds of unworthy vessels. After all, as Paul writes elsewhere, in Christ there is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, but all are one in Christ. The old distinctions that seemed to matter so much? Once we, like Job, see the face of God, we might see that we are all made in God's image, regardless of outward appearances.

Which brings me to my conclusion. Last week, a young woman in my community wrote a stirring blog post about marriage. I don't think I know enough to say very much that is wise about this matter other than what I've already said. The story of marriage in the scriptures is, it seems to me, a story that comes to us in pieces that need to be fitted together carefully, by a community. Marriage, after all, is not just about the marriage partners, but about the community that endorses, acknowledges, and protects it. In my church, at least, when two people are married, they act as priest to one another in making their vows - making this a unique sacrament - but this is usually done in the presence of a gathered community that then promises to honor and support their union. The "pieces" of marriage found in the pages of the Bible include polygamy, forcibly taking war brides, marriages of political convenience (e.g. Solomon), marriages predicated on economic necessity (e.g. Ruth), arranged marriages, marriages of love. And even divorce and remarriage - though the Bible often has particular vitriol for divorce and for the "hardness of heart" that may sometimes cause it. We don't get a rule; we get a trajectory.

That "first missionary" I mentioned? You can find her story in the fourth chapter of John's Gospel. She had been married five times, and was living with another man when Jesus met her. As far as John tells us, Jesus didn't rebuke her for this, or command her to live differently. Instead, he just let her know that he knew about her, and he continued to speak to her - something no one else in her town would do, apparently. (Even Jesus's partially enlightened disciples were astonished to find him speaking to such a woman.) He let her know he knew her, and for her, this was revelation enough. She returned to her town and told her townspeople that she was known by the Messiah. This was her Gospel.

And what a Gospel it must have been to her, that she was willing to go into the town that rejected her and tell everyone she met, everyone who hated her, that there was Good News. You may hate me, but I am known, and I am loved. Go hear for yourselves.

As I said, I'm no Biblical scholar, and I'm swimming in deep waters here. But what if we saw the stories in the Bible as offering not a simple rule but pieces of a puzzle, arrows pointing in the direction of knowing and loving one another? I'm not arguing that same-sex marriages would be free from sin; I am arguing quite the opposite, in fact, because I imagine that probably every marriage of every sort (including those that aren't called marriages) is full of unkindness and the other fruits of sin. So the task before us is, once again, to love one another, and to try to be holy.

Perhaps, rather than trying to shape laws, the church should be trying to speak a word of grace, one spoken with our lives more than anything: be holy. As you know holiness--as you are known by Holiness--work to embody it in your deepest loves. When we focus on trying to shape laws, it makes it seem that laws and power are what we most love. When our focus is on singing the joyful song of those who have chosen to try to be holy because they believe they are known by their Maker, we cannot be mistaken for people who are trying to control others. We become people who are captivated by the beauty of holiness and grace.

Again, I might be wrong, but might it not be that the whole creation is groaning to hear such a word as this? You are known. Be holy.

* Dan Savage made this claim last year; I don't think he's altogether wrong in his conclusions, and I think he's trying to do a lot of good, but he and I have different approaches to scripture, and his strikes me as hasty and dismissive. This is unfortunate, because there are few texts like the Bible when it comes to power to transform societal beliefs; and because attacking the Bible doesn't help win over those who believe it. If you don't like the popular interpretation of a text, attacking the text is not as helpful as offering a serious, scholarly rival interpretation.

** Pirke Avot 2:21

When it comes to the Bible, we've all been shaped by it, and we all have ways of responding to the pressures it has exerted while shaping us.

The early creeds try to maintain considerable latitude for how we regard the scriptures. For instance, the Nicene Creed says "We believe in the Holy Spirit...who has spoken through the prophets." Just how has the Spirit spoken, and what are we to make of that?

I'm grateful for those early Christians who, like St. Augustine, acknowledged that the scripture may have several senses. The Spirit does not speak in monotone, but in harmony, and the scriptures may sing several parts at once.

I was born into a churchgoing family, but we didn't spend much time talking about scripture. As a teenager I joined an independent church with charismatic and evangelical theology, and it was there that some of my strongest impressions of scripture were formed, in the presence of people who believed that the Spirit's voice in scripture could still be heard timelessly. While I've since grown away from that church, the idea that God speaks through scripture has stuck with me.

So not only has it shaped my life indirectly, I have sought to make myself open to it, to let it teach and guide me. Its songs and poems comfort me in hard times, and give me words when I want to express my joy and gratitude. The prophets help me to name the compass-points toward which my heart stretches. Its narratives offer opportunities for reflection on lives lived well, and poorly. And while I've made no attempt to keep all of its commandments, I find in them rules and principles that help me to live a life of "long obedience," to borrow a phrase from Nietzsche.

They give me doctrines, too, ideas about the world that make sense to me and that I don't think I could have formulated on my own. Creation, fall, and redemption; nurturing love, sin, and grace. I doubt I could explain any of these in perfectly clear and agreeable terms, but even in their vague forms (perhaps especially in their vague forms) they help me to make sense of the world.

But there is more. I take the Bible to be not just a collection of books, but a collection that holds together. The Tower of Babel in Genesis and the Tongues of Fire in Acts go together just as the Garden of Eden, the Garden of Gethsemane, and the tree-lined streets of the New Jerusalem go together. The stories of fathers and sons from Adam to Abraham, from David to Joseph, all fit together like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle; no two are alike, but taken as a whole, a larger picture forms.

This, I believe, is why the work of studying scripture matters to the communities that claim to be people of those scriptures. Putting together the puzzle is the work of our lives together.

Which is not to say that I think God is a cruel puzzle-maker. To say that would be already to have sorted out the puzzle. I'm not fond of jigsaw puzzles--when I was younger I couldn't understand why I would purchase and subject myself to an unnecessary problem. Why not just buy the picture before it's cut up? But there is real joy in playfully and willingly choosing to tackle a problem together.

So here is my small contribution to our work together: I don't think the scriptures are simply about rules and doctrines. Let's assume that God inspired the Bible; if so, and if God only wanted to deliver doctrines, God is not a very good writer. There's a lot of fluff in there that doesn't contribute directly to our list of rules.

If, on the other hand, God wanted to create a community of love and wisdom, I'm not sure there's a better way than by giving stories and poems, and by getting personally involved in that community, sharing its joys and its sorrows and its work. And if God wanted to make people who would not just obey but grow up into love and wisdom, all the more so.

This is why I take the Bible to be giving us a set of narratives that hang together, forming not a complete story but a story that is like a set of signposts, or a finger pointing in the direction we should travel. We are not static automata, nor should we strive to be. We are pilgrims with progress yet to be made. As in the myth of Pygmalion and Galatea, a loving maker wants a lover, not a lifeless statue.

More than once I've heard facile criticisms* of the Bible saying, in effect, the Bible got slavery wrong, therefore the Bible is wrong. But this is as flatfooted as saying that the U.S. Constitution got slavery wrong, and therefore the Constitution is wrong. I take the Constitution to be a good document, and part of its goodness is the way in which it allows us to grow in our understanding. As Thomas Aquinas said, no positive human law will ever suffice for all time; we will always need to be legislators striving to codify and live what is good. We should not expect to arrive at our destination under our own steam; but we must try. As the Talmud says, "It is not your job to finish the work but you are not free to walk away from it."** There is still interpretive work to be done.