stoichedon

∞

Drawing Outside The Lines: Marginalia and E-Books

I was an early adopter of the Kindle, but I stopped using it several years ago. The books I most wanted weren't (and many still aren't) available for it, and it was hard to use it as I like to use books.

You see, I am an annotator. I draw in books.

Everyone told me when I was a kid that you should NOT draw in books. But I can't help it.

Last summer my sister-in-law, seeing me read with a pencil in my hand, asked me if I always do that. I hadn't really thought about it as unusual until then, but yes, I guess I do. That way my reading becomes a kind of conversation with the book. The author writes, and I write back.

It is becoming a bit easier to annotate e-books, but we have a long way to go, perhaps because we have structured our computers to think in a linear fashion. Computers think in stoichedon, in lines and ranks, like soldiers in formation. Which is a good way to organize information, but it's not the only way, because it's not the only way lines can move. "Idea mapping" or "mind mapping" is another way. This can be expanded to three dimensions or more, as well. Think of a way a line can move and you have another way of taking notes.

Over the years I have devised my own shorthand for note-taking. For some things, I borrow old conventions of abbreviation and expand them, like this:

And so on. Some words, like selah, have entered my annotative vocabulary because they say so much so briefly. (See footnote 3 here, about "selah.")

At times, I've also found it helpful to invent new symbols, pictograms of whole ideas, sentences that can be written a single picture. I can do these with a flick of the pen, but they're much harder to incorporate into a digital text.

I draw lines from one page to the next to connect ideas. I circle names when they first appear in a text so that I can find them again. I draw vertical lines beside paragraphs to quickly highlight long sections of text. A double line emphasizes that highlighting.

I draw maps, and sketch pictures. Sometimes I write in other languages, other alphabets, when those other languages get the idea down more quickly, or more carefully. I haven't written music in books, but I don't see why you couldn't.

And all of that becomes an icon of a conversation. The annotated page is no longer text; it is an image, and a symbol of a set of relations between ideas and authors.

When I was in grad school, José Vericat (who did not know me from Adam) kindly gave me a list of books belonging to Charles Peirce and housed in one of Harvard's libraries. Peirce died in 1914, but his lines and words still illuminate his reading of those pages.

Another bit of scholarly generosity was shown to me a few years ago when I was working on my book on the environmental vision of C.S. Lewis at the Wade Center. The director, Christopher Mitchell, learned of my interest in Lewis's reading of Henri Bergson. Mitchell brought me Lewis's copy of Bergson's Évolution Créatrice to peruse. Every page is covered with marginalia written by Lewis as he recovered from his war injuries.

I think my favorite part of Thomas Cahill's book, How The Irish Saved Civilization, was seeing the facsimiles of marginal paintings - including some racy self-portraits - by monks who copied books in Ireland in the middle ages.

My point in this long blog post? Keep drawing in books. And maybe I'll get another Kindle someday if they can figure out a way to make it easy for me to draw outside the lines. And to preserve those drawings for posterity.

You see, I am an annotator. I draw in books.

Everyone told me when I was a kid that you should NOT draw in books. But I can't help it.

Last summer my sister-in-law, seeing me read with a pencil in my hand, asked me if I always do that. I hadn't really thought about it as unusual until then, but yes, I guess I do. That way my reading becomes a kind of conversation with the book. The author writes, and I write back.

It is becoming a bit easier to annotate e-books, but we have a long way to go, perhaps because we have structured our computers to think in a linear fashion. Computers think in stoichedon, in lines and ranks, like soldiers in formation. Which is a good way to organize information, but it's not the only way, because it's not the only way lines can move. "Idea mapping" or "mind mapping" is another way. This can be expanded to three dimensions or more, as well. Think of a way a line can move and you have another way of taking notes.

Over the years I have devised my own shorthand for note-taking. For some things, I borrow old conventions of abbreviation and expand them, like this:

could - cd

would - wd

should - shd

something - s/t

everything - e/t

nothing - n/t

because - b/c

nevertheless - n/t/l

And so on. Some words, like selah, have entered my annotative vocabulary because they say so much so briefly. (See footnote 3 here, about "selah.")

At times, I've also found it helpful to invent new symbols, pictograms of whole ideas, sentences that can be written a single picture. I can do these with a flick of the pen, but they're much harder to incorporate into a digital text.

I draw lines from one page to the next to connect ideas. I circle names when they first appear in a text so that I can find them again. I draw vertical lines beside paragraphs to quickly highlight long sections of text. A double line emphasizes that highlighting.

I draw maps, and sketch pictures. Sometimes I write in other languages, other alphabets, when those other languages get the idea down more quickly, or more carefully. I haven't written music in books, but I don't see why you couldn't.

And all of that becomes an icon of a conversation. The annotated page is no longer text; it is an image, and a symbol of a set of relations between ideas and authors.

When I was in grad school, José Vericat (who did not know me from Adam) kindly gave me a list of books belonging to Charles Peirce and housed in one of Harvard's libraries. Peirce died in 1914, but his lines and words still illuminate his reading of those pages.

Another bit of scholarly generosity was shown to me a few years ago when I was working on my book on the environmental vision of C.S. Lewis at the Wade Center. The director, Christopher Mitchell, learned of my interest in Lewis's reading of Henri Bergson. Mitchell brought me Lewis's copy of Bergson's Évolution Créatrice to peruse. Every page is covered with marginalia written by Lewis as he recovered from his war injuries.

I think my favorite part of Thomas Cahill's book, How The Irish Saved Civilization, was seeing the facsimiles of marginal paintings - including some racy self-portraits - by monks who copied books in Ireland in the middle ages.

My point in this long blog post? Keep drawing in books. And maybe I'll get another Kindle someday if they can figure out a way to make it easy for me to draw outside the lines. And to preserve those drawings for posterity.

∞

Writing, Law, and Memory in Ancient Gortyn

In the ruins of Gortyn, in central Crete, some of the famous ancient laws of Crete are preserved in stone. Archaeologists uncovered them in 1884, and have since built a brick enclosure to protect them from the weather.

Even though I'm not an expert in the Doric dialect, I love to read this inscription, for several reasons that might interest even those who don't know Greek.

First of all, it has an unusual alphabet, containing fewer letters than modern or classical Attic Greek. It lacks the vowels eta and omega (for which it uses epsilon and omicron), and the consonants zeta, xi, phi, chi, and psi (for which it substitutes other letters or combinations of other letters: two deltas for zeta, kappa+sigma for xi; pi for phi; kappa for chi; pi+sigma for psi.)

It also uses a letter that has since fallen out of use, the digamma. The digamma (or wau) is probably related to the Hebrew letter waw (or vav) and to the Roman letter F, which it closely resembles. By the classical age it had dropped out of use in Greek, and is fairly rare, like the letters sampi and qoppa.

(There is also a digamma in Delphi, not far from the Athena Pronaia sanctuary, on an upright stone dedicated to Athenai Warganai. That second word is related to the Greek word for "work" or "deed," ergon, and also to our word "work." This stone, pictured below, evinces several peculiarities of archaic Greek script. Look at the second word, which looks like it says FARCANAI. The first letter is digamma; the third letter, rho, very much resembles the Latin "R"; the letter immediately after it, gamma, looks like a flattened upper-case "C.")

Second, the writing is in boustrophedon style. Boustrophedon means something like "as the ox turns." Today we write in stoichedon style, in which all the letters face the same direction, like soldiers standing in formation. Boustrophedon is based on an agricultural, not a military ideal: the writer writes as a farmer plows. Write to the end of the line, and then, rather than returning to the left side of the page, turn the letters to face the opposite direction and write from right to left. When you read boustrophedon, your eye follows a zig-zag across the page -- or the stone.

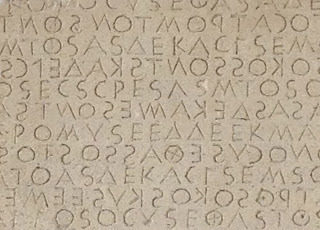

Have a look at this close-up of the engraving at Gortys and look at the way letters like "E," "K," and "S" face in adjacent lines:

(By the way, that "S" character is actually an iota; sigmas look like this: M; mu is like our "M" with an extra stroke added.)

There are a lot of other reasons to like this place, and this inscription, but I'll limit myself to just one more thing for now: memory.

This inscription is one way that an ancient community deliberately remembered their laws. They wrote down what they decided, and that has affected our lives. Writing the law down makes it accessible to everyone, and makes judicial decisions transparent. It establishes a set of expectations for conduct in the community, and makes those expectations known even to aliens.

The code at Gortyn records (in Column IX, around the middle, if you're curious) the presence at court of someone in addition to the judge: the mnemon. You can see by the word's resemblance to our word "mnemonic" that it has to do with memory. The mnemon's job was to act as a witness to previous judicial decisions, and to remember them and remind the judge of those decisions. The mnemon's job was not to decide cases but to be a kind of embodiment of the law and therefore an embodiment of fairness.

Unfortunately, no mnemon lives forever. Presumably, the writing on the wall at Gortyn was a way of preserving what mattered most in the court, so that when they passed away, their memories would live on through the ages.

*****

Harold Fowler writes in a footnote to his 1921 translation of the Cratylus that under Eucleides the Athenians officially changed their alphabet from the archaic one to the Ionian alphabet in 404/403 BCE. This expanded their system of vowels, adding the long vowels eta and omega. It became known as the Euclidean Alphabet.

*****

If you can find it, Adonis Vasilakis' The Great Inscription of the Law Code of Gortyn (Heraklion/Iraklio: Mystis O.E.) is a great resource. It has a facsimile of the whole wall, a complete translation, and some helpful historical observations. ISBN 9608853400

|

| Gortyn, Crete |

Even though I'm not an expert in the Doric dialect, I love to read this inscription, for several reasons that might interest even those who don't know Greek.

First of all, it has an unusual alphabet, containing fewer letters than modern or classical Attic Greek. It lacks the vowels eta and omega (for which it uses epsilon and omicron), and the consonants zeta, xi, phi, chi, and psi (for which it substitutes other letters or combinations of other letters: two deltas for zeta, kappa+sigma for xi; pi for phi; kappa for chi; pi+sigma for psi.)

It also uses a letter that has since fallen out of use, the digamma. The digamma (or wau) is probably related to the Hebrew letter waw (or vav) and to the Roman letter F, which it closely resembles. By the classical age it had dropped out of use in Greek, and is fairly rare, like the letters sampi and qoppa.

(There is also a digamma in Delphi, not far from the Athena Pronaia sanctuary, on an upright stone dedicated to Athenai Warganai. That second word is related to the Greek word for "work" or "deed," ergon, and also to our word "work." This stone, pictured below, evinces several peculiarities of archaic Greek script. Look at the second word, which looks like it says FARCANAI. The first letter is digamma; the third letter, rho, very much resembles the Latin "R"; the letter immediately after it, gamma, looks like a flattened upper-case "C.")

|

|

"Athenai Warganai" inscription at Delphi

|

Second, the writing is in boustrophedon style. Boustrophedon means something like "as the ox turns." Today we write in stoichedon style, in which all the letters face the same direction, like soldiers standing in formation. Boustrophedon is based on an agricultural, not a military ideal: the writer writes as a farmer plows. Write to the end of the line, and then, rather than returning to the left side of the page, turn the letters to face the opposite direction and write from right to left. When you read boustrophedon, your eye follows a zig-zag across the page -- or the stone.

Have a look at this close-up of the engraving at Gortys and look at the way letters like "E," "K," and "S" face in adjacent lines:

|

| Close-up of the Gortyn Code |

There are a lot of other reasons to like this place, and this inscription, but I'll limit myself to just one more thing for now: memory.

This inscription is one way that an ancient community deliberately remembered their laws. They wrote down what they decided, and that has affected our lives. Writing the law down makes it accessible to everyone, and makes judicial decisions transparent. It establishes a set of expectations for conduct in the community, and makes those expectations known even to aliens.

The code at Gortyn records (in Column IX, around the middle, if you're curious) the presence at court of someone in addition to the judge: the mnemon. You can see by the word's resemblance to our word "mnemonic" that it has to do with memory. The mnemon's job was to act as a witness to previous judicial decisions, and to remember them and remind the judge of those decisions. The mnemon's job was not to decide cases but to be a kind of embodiment of the law and therefore an embodiment of fairness.

Unfortunately, no mnemon lives forever. Presumably, the writing on the wall at Gortyn was a way of preserving what mattered most in the court, so that when they passed away, their memories would live on through the ages.

|

| National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Possibly a child's dish? The sixth letter is digamma. |

*****

Harold Fowler writes in a footnote to his 1921 translation of the Cratylus that under Eucleides the Athenians officially changed their alphabet from the archaic one to the Ionian alphabet in 404/403 BCE. This expanded their system of vowels, adding the long vowels eta and omega. It became known as the Euclidean Alphabet.

*****

If you can find it, Adonis Vasilakis' The Great Inscription of the Law Code of Gortyn (Heraklion/Iraklio: Mystis O.E.) is a great resource. It has a facsimile of the whole wall, a complete translation, and some helpful historical observations. ISBN 9608853400