Stoicism

- This too is related to technology, of course. If the class is focused on video screens, then all the chairs will face the screens, and the classroom might even be structured like a theater. Etymologically, "theater" means something like "a place of gazing," and theaters tend to encourage people to gaze. Sometimes this can work against other activities, like colloquy, small-group interaction, and really anything that involves students moving from one place to another.

- If that last sentence made you ask,"But why do you want your students to move from one place to another?" then you see that we have some pretty strong presuppositions about how education should happen: students should sit and listen, teachers should stand and lecture. This communicates something about authority, and at times that's helpful. But it can also invite students to lean back into passivity, and to assume they have no role in their own education.

- The furniture in classrooms tells us how people are to behave, because it has been made and purchased by people who had in mind some idea of how students should behave. Most wrap-around desks are made for right-handed people, for instance. And most classroom desks I've seen expect students to sit upright, at attention, with a book open in front of them. I really don't like those desks, and I feel trapped when I sit in them. I wonder sometimes how they make my students feel. I wish we had fewer chairs and more sofas. Maybe a fireplace, or some tables with glasses of water, and ashtrays on them. I suppose I wish I could teach in pubs or ratskellers, which are, after all, places consciously designed for people to meet and discuss what most matters to them, informally, passionately, amicably.

- Classrooms that privilege video screens tend to undervalue natural light and windows. I am reminded of Emerson's reflection on a boring sermon he once heard. Emerson wrote, in his Divinity School Address, that while the minister droned on, Emerson looked out the window at the falling snow, which, he proclaimed, preached a better sermon than the minister. I have no doubt that nature can often give a better lecture than I can.

∞

Reason For Hope

Nearly every spring term I teach a class called “Theology and Philosophy in Dialogue.” I inherited the title and the course description when I started teaching at my current school in 2005. Each year the course changes a little, in response to my students and what I perceive to be relevant themes in our world and culture.

Apologetics and Postmodernism

When I first taught it, I made it a class about apologetics and postmodernism. By “apologetics” I mean the work of giving a reasoned account of one’s commitments; by “postmodernism,” I mean the suspicion that what look like reasoned accounts might have unexamined depths and layers to them. In the context of theism—and in particular Christian theism—apologetics has a long history that reaches back to the early years of Christianity. Saint Peter wrote in his longer letter that Christians should always be prepared to give a reasoned defense of the hope they bore within them. That phrase “reasoned defense” is a translation of the Greek word apologia, which can mean a legal defense, and from which we get our word “apologetics.”

When Saint Paul of Tarsus found himself in Athens, speaking to Stoic and Epicurean philosophers on the Areopagus, he tried to explain his beliefs not in the terms of his culture but in theirs. He doesn’t seem to have won many over to his views that day, but if nothing else was accomplished, at the end of the conversation it was clearer where Paul and the Greek philosophers were in agreement and where they disagreed. If immediate conversion was the aim of his speech, it wasn’t a great speech. But if he aimed to build a bridge of mutual understanding, I’d say he was pretty successful.

One of the keys to his success, I think, was familiarity with the culture around him. I’ve written about this elsewhere, so I won’t belabor it here, but I’ll just point out that Paul quoted two Greek philosophical poets, Epimenides and Aratos, and he did so in a culturally appropriate and significant place, since several centuries before Paul’s travels, Epimenides (who was from Crete) also traveled to Athens and also spoke on the Areopagus about the gods and salvation.

Understanding Atheism(s)

A few years after I started teaching that course, I shifted the course to take seriously the “New Atheists.” I figured that if my religious students graduated without hearing the strongest challenges to their faith, I, as a professor who teaches theology, was letting them down. I wanted them to know that soon they’d hear strong arguments against their religious heritage, beliefs, and practices, and that these arguments should be taken seriously. For my Christian students, I framed this as a way of living the commandment to love God with one’s mind.

Of course, only some of my students are religious, and some of the religious students aren’t Christians. (I’m at a Lutheran university in a small Midwestern city, so until recently most of them were at least culturally Christian; that’s changing quickly, though.) I wanted this to be a class that was helpful for everyone, so I started to turn this into a class about mutual understanding. I now teach my students how to distinguish between a dozen different kinds of (and reasons for) atheism, lest they make the mistake of oversimplifying the complexity of their neighbors and of themselves.

Understanding and Agapic Love

Arguments about religion can quickly become unkind. Many of us have been wounded in the name of religion, and those wounds heal slowly, if at all. How could we make this into a class that was—on its surface, and in its content—about theology and philosophy, while really making it about something like mutual care?

I just mentioned that great commandment: Love God with your heart, soul, mind, and strength, Jesus said, echoing Moses. Then he added a second commandment: love your neighbor as yourself. Everything else hangs on these two commandments, he said.

Explaining those two commandments would be almost as hard as trying to keep them, so I won’t try to do so here. I’ll just point out that it’s fascinating to command someone to love someone else; that the love that’s called for here is agapic love, i.e. the love that seeks the good and flourishing of the beloved; and that the commandments are so lacking in specificity as to call for both extensive commentary and continued practice. They’re vague commandments, which means they require us to work them out in community, over time. And in all likelihood we’ll never get them right. That may seem like a weakness, but it also strikes me as offering the freedom to try and to fail and to help one another to try again.

Anxiety, Ultimate Concerns, and Societal “Stress Fractures”

Which brings me to the most recent incarnation of my Theology and Philosophy in Dialogue class. Over the last few years it seems to me that my students have become more anxious about their economic futures, more stressed about exams and jobs, more focused on education and work as competition for rank. I could be wrong, but as the stress and anxiety have grown, it seems like my students are so busy jockeying for position that they have a hard time putting the cause of their stress into words. On top of all this, here in the United States, it feels like we’ve been using stronger words so that we can give voice to our anxiety more quickly. We aren’t broken, but we’ve got lots of hairline stress fractures that are too small to see. We aren’t bleeding, but we’ve got a constant dull ache.

In other words, it seems like we’re fearful without being able to identify the object of our fear, and that has us prepared to see enemies wherever we look. This does not make it easy to love our neighbors as ourselves (unless we also have that kind of distrust of ourselves, which is a real possibility, I suppose.) And at least in the way Paul Tillich described God: whatever we regard as our ultimate concern functions as our God. When economic anxiety, jostling for rank, or fear of losing one’s place in the future, (these are all ways of saying the same thing, I think) take on the role of “ultimate concern” in our lives, they become our gods.

The course I’m teaching this semester still has traces of every previous semester’s influences. We talk a little about apologetics, and that’s a helpful way of teaching students about logic, inference, probability, and certainty. (Ask some of them about “doxastic certainty” or my “haystack problem” and you’ll see what I mean.)

And we still talk about postmodernism, though as my career has shifted from the philosophy of religion to environmental philosophy, ethics, and policy, I’m inclined to follow Scott Russell Sanders’ view (see note, below) that if we spend too much time theorizing and not enough time caring for the world we share, incredulity towards metanarratives can quickly become a new metanarrative that we fail to examine sufficiently.

And we still talk about atheisms. This semester I have sketched a dozen forms of atheism once again, and we’re now working our way through them.

Friendship, and “Best Construction”

But the aim of the class, more than anything, is friendship.

I told all the students that this was the case on the first day of class.

And here, I think, is where Theology and Philosophy can have a really helpful dialogue in our time. I teach at a Lutheran university, so it’s fitting to invoke Luther. In his Small Catechism, he offers some commentary on the Ten Commandments. His commentary on the eighth commandment is helpful. The commandment reads simply, like this:

This is hard.

“A Mutual, Joint-Stock World, In All Meridians”

It’s especially hard when we feel that others are getting ahead of us, and that we are in a competition with everyone else. If the world is a zero-sum game, then everyone run, and the Devil take the hindmost. But what if Queequeg is right? When Queequeg sees a fellow sailor drowning and no one moves to save the sailor, Queequeg leaps into the water to save his fellow. There is no question of whether they are of the same tribe, the same party, the same race, the same team. Queequeg is, as far as anyone aboard the ship knows, a cannibal. And yet the narrator, observing Queequeg’s agapic care for his fellow sailor, offers this comment:

It’s much easier to approach theological conversations with the idea that our theology is a weapon and that our enemies are those with whom we disagree. It’s so easy to forget what Saint Paul wrote, that we don’t fight against flesh and blood, but against far less tangible, invisible forces that would have us view our neighbors with malice.

Could we approach theology the way Queequeg approaches the plight of his fellow sailor? Is it possible to maintain one’s cherished beliefs while recognizing that one’s object of “ultimate concern” might be something we don’t yet see with certainty and clarity? I cannot speak for others, so I’ll just offer this confession: I’m aware of a capacity in myself to care more for my theology than for the God that my theology claims to describe. In simpler terms: my own theology can become so dear to me that it becomes an idol, displacing the very God I set out to love and serve. And how to I love and serve my God? So far, the best I can offer you is this: I should love God with all I am, and I should love my neighbor as myself. Does that seem unclear to you? It does to me. Which means I need all the help I can get in clarifying my vision. Right now I see in a glass, darkly.

The philosopher Jonathan Lear suggests a principle akin to Queequeg’s, and to Luther’s: the principle of humanity. He describes it like this:

Conclusion

It’s appropriate to me that I teach this course in Lent each year. Lent is a good time for self-examination, and that includes an examination of all kinds of pieties and supposed certainties. What is it that we hold to be of ultimate concern? What do we love with all our heart, soul, mind, and strength? That might just be playing the role of a god in our lives. If so, does that God help us to love our neighbors as ourselves?

I could be wrong in all I say in this class. I enter it with “fear and trembling,” knowing that there’s so much I don’t know, and knowing that many of my students might be wiser than I am. I know they might have seen the divine far more clearly than I ever will in this life.

But oh, how I want them to live well, not to be entangled by anxious grief, not to be afraid of the future, not to be burdened by relentless suspicions and fears.

Yes, there are other subjects I could teach, and yes, there are other jobs I could do. But for me, right now, this one feels like a good way to reexamine my own ultimate concerns, and a good way to help others to do the same. May I do so without malice, with agapic love, and with the constant practice of putting the best construction on everything.

Amen. Lord, have mercy.

*****

Notes:

* Scott Russell Sanders: I'm thinking of his essay, "The Warehouse and the Wilderness," and in particular the opening pages of that essay. You can find it in A Conservationist Manifesto, beginning on page 71. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009)

* Ulpian's words are cited in Justinian, Institutes, Book 1, Title 1, Sec. 3.

* Lear has an endnote at the end of this sentence. It reads: “This principle is also known as the ‘principle of charity,’ and the most famous arguments for it are given by Donald Davidson. See his “Radical Interpretation,” in Inquiries Into Truth And Interpretation (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984), pp. 136-137; “Belief and the Basis of Meaning,” ibid., pp. 152-153; “Thought and Talk,” ibid., pp. 168-169; “On the Very Idea of a Conceptual Scheme,” ibid., pp. 196-197; “The Method of Truth in Metaphysics,” ibid., pp. 200-201.”

Apologetics and Postmodernism

When I first taught it, I made it a class about apologetics and postmodernism. By “apologetics” I mean the work of giving a reasoned account of one’s commitments; by “postmodernism,” I mean the suspicion that what look like reasoned accounts might have unexamined depths and layers to them. In the context of theism—and in particular Christian theism—apologetics has a long history that reaches back to the early years of Christianity. Saint Peter wrote in his longer letter that Christians should always be prepared to give a reasoned defense of the hope they bore within them. That phrase “reasoned defense” is a translation of the Greek word apologia, which can mean a legal defense, and from which we get our word “apologetics.”

When Saint Paul of Tarsus found himself in Athens, speaking to Stoic and Epicurean philosophers on the Areopagus, he tried to explain his beliefs not in the terms of his culture but in theirs. He doesn’t seem to have won many over to his views that day, but if nothing else was accomplished, at the end of the conversation it was clearer where Paul and the Greek philosophers were in agreement and where they disagreed. If immediate conversion was the aim of his speech, it wasn’t a great speech. But if he aimed to build a bridge of mutual understanding, I’d say he was pretty successful.

One of the keys to his success, I think, was familiarity with the culture around him. I’ve written about this elsewhere, so I won’t belabor it here, but I’ll just point out that Paul quoted two Greek philosophical poets, Epimenides and Aratos, and he did so in a culturally appropriate and significant place, since several centuries before Paul’s travels, Epimenides (who was from Crete) also traveled to Athens and also spoke on the Areopagus about the gods and salvation.

Understanding Atheism(s)

A few years after I started teaching that course, I shifted the course to take seriously the “New Atheists.” I figured that if my religious students graduated without hearing the strongest challenges to their faith, I, as a professor who teaches theology, was letting them down. I wanted them to know that soon they’d hear strong arguments against their religious heritage, beliefs, and practices, and that these arguments should be taken seriously. For my Christian students, I framed this as a way of living the commandment to love God with one’s mind.

Of course, only some of my students are religious, and some of the religious students aren’t Christians. (I’m at a Lutheran university in a small Midwestern city, so until recently most of them were at least culturally Christian; that’s changing quickly, though.) I wanted this to be a class that was helpful for everyone, so I started to turn this into a class about mutual understanding. I now teach my students how to distinguish between a dozen different kinds of (and reasons for) atheism, lest they make the mistake of oversimplifying the complexity of their neighbors and of themselves.

Understanding and Agapic Love

Arguments about religion can quickly become unkind. Many of us have been wounded in the name of religion, and those wounds heal slowly, if at all. How could we make this into a class that was—on its surface, and in its content—about theology and philosophy, while really making it about something like mutual care?

I just mentioned that great commandment: Love God with your heart, soul, mind, and strength, Jesus said, echoing Moses. Then he added a second commandment: love your neighbor as yourself. Everything else hangs on these two commandments, he said.

Explaining those two commandments would be almost as hard as trying to keep them, so I won’t try to do so here. I’ll just point out that it’s fascinating to command someone to love someone else; that the love that’s called for here is agapic love, i.e. the love that seeks the good and flourishing of the beloved; and that the commandments are so lacking in specificity as to call for both extensive commentary and continued practice. They’re vague commandments, which means they require us to work them out in community, over time. And in all likelihood we’ll never get them right. That may seem like a weakness, but it also strikes me as offering the freedom to try and to fail and to help one another to try again.

Anxiety, Ultimate Concerns, and Societal “Stress Fractures”

Which brings me to the most recent incarnation of my Theology and Philosophy in Dialogue class. Over the last few years it seems to me that my students have become more anxious about their economic futures, more stressed about exams and jobs, more focused on education and work as competition for rank. I could be wrong, but as the stress and anxiety have grown, it seems like my students are so busy jockeying for position that they have a hard time putting the cause of their stress into words. On top of all this, here in the United States, it feels like we’ve been using stronger words so that we can give voice to our anxiety more quickly. We aren’t broken, but we’ve got lots of hairline stress fractures that are too small to see. We aren’t bleeding, but we’ve got a constant dull ache.

In other words, it seems like we’re fearful without being able to identify the object of our fear, and that has us prepared to see enemies wherever we look. This does not make it easy to love our neighbors as ourselves (unless we also have that kind of distrust of ourselves, which is a real possibility, I suppose.) And at least in the way Paul Tillich described God: whatever we regard as our ultimate concern functions as our God. When economic anxiety, jostling for rank, or fear of losing one’s place in the future, (these are all ways of saying the same thing, I think) take on the role of “ultimate concern” in our lives, they become our gods.

The course I’m teaching this semester still has traces of every previous semester’s influences. We talk a little about apologetics, and that’s a helpful way of teaching students about logic, inference, probability, and certainty. (Ask some of them about “doxastic certainty” or my “haystack problem” and you’ll see what I mean.)

And we still talk about postmodernism, though as my career has shifted from the philosophy of religion to environmental philosophy, ethics, and policy, I’m inclined to follow Scott Russell Sanders’ view (see note, below) that if we spend too much time theorizing and not enough time caring for the world we share, incredulity towards metanarratives can quickly become a new metanarrative that we fail to examine sufficiently.

And we still talk about atheisms. This semester I have sketched a dozen forms of atheism once again, and we’re now working our way through them.

Friendship, and “Best Construction”

But the aim of the class, more than anything, is friendship.

I told all the students that this was the case on the first day of class.

And here, I think, is where Theology and Philosophy can have a really helpful dialogue in our time. I teach at a Lutheran university, so it’s fitting to invoke Luther. In his Small Catechism, he offers some commentary on the Ten Commandments. His commentary on the eighth commandment is helpful. The commandment reads simply, like this:

“Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor.”Like the other commandments I’ve mentioned, it is only a few words long. And like those others, it leaves room for commentary. Luther’s commentary does something that I find very helpful. While the commandment is negative (“thou shalt not,” it says) Luther thought that alongside each negative commandment was something positive. So he writes:

What does this mean?--Answer. We should fear and love God that we may not deceitfully belie, betray, slander, or defame our neighbor, but defend him, [think and] speak well of him, and put the best construction on everything.”This is akin to what Plato offers in several ways in his Republic, and to Ulpian’s legal principle of “giving to each person their due,” (see note, below) but it goes a little further, with an agapic tinge: Luther doesn’t just tell us not to lie, nor does he tell us to be simply honest, but to put the best construction on everything.

This is hard.

“A Mutual, Joint-Stock World, In All Meridians”

It’s especially hard when we feel that others are getting ahead of us, and that we are in a competition with everyone else. If the world is a zero-sum game, then everyone run, and the Devil take the hindmost. But what if Queequeg is right? When Queequeg sees a fellow sailor drowning and no one moves to save the sailor, Queequeg leaps into the water to save his fellow. There is no question of whether they are of the same tribe, the same party, the same race, the same team. Queequeg is, as far as anyone aboard the ship knows, a cannibal. And yet the narrator, observing Queequeg’s agapic care for his fellow sailor, offers this comment:

Was there ever such unconsciousness? He did not seem to think that he at all deserved a medal from the Humane and Magnanimous Societies. He only asked for water—fresh water—something to wipe the brine off; that done, he put on dry clothes, lighted his pipe, and leaning against the bulwarks, and mildly eyeing those around him, seemed to be saying to himself—“It’s a mutual, joint-stock world, in all meridians. We cannibals must help these Christians.” -- Herman Melville, Moby Dick. (New York: Signet, 1980) 76

It’s much easier to approach theological conversations with the idea that our theology is a weapon and that our enemies are those with whom we disagree. It’s so easy to forget what Saint Paul wrote, that we don’t fight against flesh and blood, but against far less tangible, invisible forces that would have us view our neighbors with malice.

Could we approach theology the way Queequeg approaches the plight of his fellow sailor? Is it possible to maintain one’s cherished beliefs while recognizing that one’s object of “ultimate concern” might be something we don’t yet see with certainty and clarity? I cannot speak for others, so I’ll just offer this confession: I’m aware of a capacity in myself to care more for my theology than for the God that my theology claims to describe. In simpler terms: my own theology can become so dear to me that it becomes an idol, displacing the very God I set out to love and serve. And how to I love and serve my God? So far, the best I can offer you is this: I should love God with all I am, and I should love my neighbor as myself. Does that seem unclear to you? It does to me. Which means I need all the help I can get in clarifying my vision. Right now I see in a glass, darkly.

The philosopher Jonathan Lear suggests a principle akin to Queequeg’s, and to Luther’s: the principle of humanity. He describes it like this:

“The interpretation thus fits what philosophers call the principle of humanity: that we should try to interpret others as saying something true—guided by our own sense of what is true and of what they could reasonably believe.” -- Jonathan Lear, Radical Hope. 4 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006) (See note below)The Episcopal Church’s Book of Common Prayer offers another commentary on the fourth commandment, the commandment not to take the name of God in vain. The Book of Common Prayer rephrases the commandment like this:

You shall not invoke with malice the Name of the Lord your God.

Amen. Lord have mercy.The rephrasing is a commentary on “in vain.” Invoking God’s name in vain is equated with invoking it with malice, that is, with the opposite of agapic love.

Conclusion

It’s appropriate to me that I teach this course in Lent each year. Lent is a good time for self-examination, and that includes an examination of all kinds of pieties and supposed certainties. What is it that we hold to be of ultimate concern? What do we love with all our heart, soul, mind, and strength? That might just be playing the role of a god in our lives. If so, does that God help us to love our neighbors as ourselves?

I could be wrong in all I say in this class. I enter it with “fear and trembling,” knowing that there’s so much I don’t know, and knowing that many of my students might be wiser than I am. I know they might have seen the divine far more clearly than I ever will in this life.

But oh, how I want them to live well, not to be entangled by anxious grief, not to be afraid of the future, not to be burdened by relentless suspicions and fears.

Yes, there are other subjects I could teach, and yes, there are other jobs I could do. But for me, right now, this one feels like a good way to reexamine my own ultimate concerns, and a good way to help others to do the same. May I do so without malice, with agapic love, and with the constant practice of putting the best construction on everything.

Amen. Lord, have mercy.

*****

Notes:

* Scott Russell Sanders: I'm thinking of his essay, "The Warehouse and the Wilderness," and in particular the opening pages of that essay. You can find it in A Conservationist Manifesto, beginning on page 71. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009)

* Ulpian's words are cited in Justinian, Institutes, Book 1, Title 1, Sec. 3.

* Lear has an endnote at the end of this sentence. It reads: “This principle is also known as the ‘principle of charity,’ and the most famous arguments for it are given by Donald Davidson. See his “Radical Interpretation,” in Inquiries Into Truth And Interpretation (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984), pp. 136-137; “Belief and the Basis of Meaning,” ibid., pp. 152-153; “Thought and Talk,” ibid., pp. 168-169; “On the Very Idea of a Conceptual Scheme,” ibid., pp. 196-197; “The Method of Truth in Metaphysics,” ibid., pp. 200-201.”

∞

What Are Philosophy's Flaws?

Last week I suggested to one of my students that she would make a good philosophy major. A few days later she came to my office and asked me, "What are philosophy's flaws?"

She wanted to know, she said, because she was thinking seriously about studying more philosophy, and for her, thinking seriously about something means considering something from all angles. She knows that ideas give birth to other ideas, and to practical consequences.

I don't think I gave her a very good answer at the time, but I've continued to think about it because it strikes me as a good question asked for a good reason.

Not long ago I was re-reading the Stoic philosopher Gaius Musonius Rufus. Of the four major Roman Stoics, he's probably the least well-known. Epictetus, Seneca and Marcus Aurelius all left substantial writings, but Musonius did not.

Rather, Musonius is known chiefly through the notes his students left behind. In fact, this is one of the reasons I like him so well: whatever became of his writings, his life made a difference for his students. His teaching mattered so much that they refused to let his life vanish from history.

There's another reason I like Musonius: he insisted that philosophy is for women, not just for men. Since the student whom I invited to study philosophy is also a woman, I want to try to give a better answer to her question by turning to Musonius now.

Once, when Musonius made the bold invitation for women to join the Stoic philosophers, someone asked him: won't studying philosophy make the women obstinate, independent, and opinionated?

He replied that in fact, it might do just that. Musonius recognized that the question was a question about the same thing my student was asking about: philosophy's flaws. Philosophy often makes us better thinkers, but it can also make us obnoxious to our neighbors when we care more about the ideas than about the people whose lives are connected to the ideas.

Musonius then quickly pointed out that the question is irrelevant, however, because what is true of women is also true of men in this regard. Like Augustine several centuries later, Musonius argued that women and men have equal intellectual powers. If philosophy entails the development and strengthening of our native intellect, then surely women will benefit from it just as much as men.

It would appear that the questioner wasn't concerned about people becoming opinionated, independent thinkers, but about women becoming opinionated, independent thinkers. What began as a question about the vices of philosophy quickly exposes itself as a question that reveals the bias of the questioner -- a bias that philosophy would be more than happy to correct.

This brings me to my student's question: Yes, philosophy has flaws, and one of its chief flaws is that when it is combined with a lack of kindness, it can amplify that unkindness.

But it also has the power to expose that unkindness in a pretty keen way. And when it is combined with kindness and positive regard for our neighbors -- with what we sometimes call agapé, or love -- it can be something that causes kindness to grow.

I don't mean that philosophy is a panacaea, or that it will do all good things for us, all on its unattended own.

But I do mean that you, my student, have very real native intelligence, and it pleases me to see it in you. And I would love to see it grow. To point to Augustine once more: Augustine found philosophy to be helpful for his own self-understanding, for his seeking after God, and for keeping his church from descending into irrationality. He regarded it as a way to "love God with his mind."

I wouldn't ask you, my student, to give up your nursing major. Quite the opposite! Just as surely as women need philosophy, I think nurses and business majors and scientists and poets need philosophy, too. I think that studying philosophy will make you a better nurse, one more able to improve the nursing profession and to improve your workplace.

And let me add one more thing. When you came into my office the other day to ask me that brilliant question, one thing was quite clear to me: whether or not you choose to make philosophy your formal major, you are already becoming a philosopher. And that makes me very happy indeed.

She wanted to know, she said, because she was thinking seriously about studying more philosophy, and for her, thinking seriously about something means considering something from all angles. She knows that ideas give birth to other ideas, and to practical consequences.

I don't think I gave her a very good answer at the time, but I've continued to think about it because it strikes me as a good question asked for a good reason.

Not long ago I was re-reading the Stoic philosopher Gaius Musonius Rufus. Of the four major Roman Stoics, he's probably the least well-known. Epictetus, Seneca and Marcus Aurelius all left substantial writings, but Musonius did not.

Rather, Musonius is known chiefly through the notes his students left behind. In fact, this is one of the reasons I like him so well: whatever became of his writings, his life made a difference for his students. His teaching mattered so much that they refused to let his life vanish from history.

There's another reason I like Musonius: he insisted that philosophy is for women, not just for men. Since the student whom I invited to study philosophy is also a woman, I want to try to give a better answer to her question by turning to Musonius now.

Once, when Musonius made the bold invitation for women to join the Stoic philosophers, someone asked him: won't studying philosophy make the women obstinate, independent, and opinionated?

He replied that in fact, it might do just that. Musonius recognized that the question was a question about the same thing my student was asking about: philosophy's flaws. Philosophy often makes us better thinkers, but it can also make us obnoxious to our neighbors when we care more about the ideas than about the people whose lives are connected to the ideas.

Musonius then quickly pointed out that the question is irrelevant, however, because what is true of women is also true of men in this regard. Like Augustine several centuries later, Musonius argued that women and men have equal intellectual powers. If philosophy entails the development and strengthening of our native intellect, then surely women will benefit from it just as much as men.

It would appear that the questioner wasn't concerned about people becoming opinionated, independent thinkers, but about women becoming opinionated, independent thinkers. What began as a question about the vices of philosophy quickly exposes itself as a question that reveals the bias of the questioner -- a bias that philosophy would be more than happy to correct.

This brings me to my student's question: Yes, philosophy has flaws, and one of its chief flaws is that when it is combined with a lack of kindness, it can amplify that unkindness.

But it also has the power to expose that unkindness in a pretty keen way. And when it is combined with kindness and positive regard for our neighbors -- with what we sometimes call agapé, or love -- it can be something that causes kindness to grow.

I don't mean that philosophy is a panacaea, or that it will do all good things for us, all on its unattended own.

But I do mean that you, my student, have very real native intelligence, and it pleases me to see it in you. And I would love to see it grow. To point to Augustine once more: Augustine found philosophy to be helpful for his own self-understanding, for his seeking after God, and for keeping his church from descending into irrationality. He regarded it as a way to "love God with his mind."

I wouldn't ask you, my student, to give up your nursing major. Quite the opposite! Just as surely as women need philosophy, I think nurses and business majors and scientists and poets need philosophy, too. I think that studying philosophy will make you a better nurse, one more able to improve the nursing profession and to improve your workplace.

And let me add one more thing. When you came into my office the other day to ask me that brilliant question, one thing was quite clear to me: whether or not you choose to make philosophy your formal major, you are already becoming a philosopher. And that makes me very happy indeed.

∞

Pragmatic Stoic Theology

In preparing a class on later Stoicism, I came across a passage from Cicero's De Natura Deorum, or On The Nature Of The Gods. Cicero himself is not one to take sides, but he attempts to practice that virtue of presenting the views of others as fairly as he can. As part of this practice, Cicero attributes a god-argument to the Stoic Chrysippus in Book 2, section 16 (Latin text here) of his De Natura Deorum.

Chrysippus' god-argument is not, strictly speaking, a proof of the existence of a god. It is rather an appeal to what he thinks is common sense, and to the consequences of not believing.

The first part, the appeal to common sense, goes something like this:

The second part makes a case that at least invites us to be cautious about dismissing it too readily. It goes like this:

But the most helpful part, I think, is (4), which stands as an invitation to consider who we are as we face the cosmos. We think of ourselves as natural, but we also think of ourselves as standing somehow apart from nature.

So it may be that there is nothing in the cosmos wiser or more clever than we are. We should be honest about this and acknowledge the real possibility that this is the case.

But Chrysippus invites us also to consider the consequences of that belief, since it could be taken as license to act as we will. The danger, as he sees it, is that we might become the sort of people who worship ourselves. This is dangerous in part because it impedes growth; we become like what we worship, and if we worship only ourselves, then we become our own best ideal. I will speak for myself when I say that I, at least, am a cramped and stingy ideal.

Many of the Stoics are content to name nature as god; what matters is that there always be something worth our attention and admiration. I'm reminded of the wise words of David Foster Wallace, who said that

Wallace comes pretty close to Chrysippus. Neither is trying to convert you to a religion, neither is trying to set the rules for your life, but both are reporting on what they have seen when they have ventured in the direction of denying all the gods: off in that direction, they found they could escape all the gods except the god they then found that they forced themselves to become.

Which, to paraphrase Wallace, is a good reason for choosing to posit some god which, if it existed, would be worth your worship. And then, maybe, to test it by trying to worship it as though it were really there.

Chrysippus' god-argument is not, strictly speaking, a proof of the existence of a god. It is rather an appeal to what he thinks is common sense, and to the consequences of not believing.

The first part, the appeal to common sense, goes something like this:

1) If there is anything in nature that we can't have made then something greater than us made it;

2) That something is what we call a god.Of course, he is assuming that everything that exists must exist because it was made, and that it was made designedly by a single cause. We could object that natural arrangements might have more than one lesser natural cause; or we could contest the whole notion of greater and lesser and dismiss this part of his argument fairly easily.

The second part makes a case that at least invites us to be cautious about dismissing it too readily. It goes like this:

3) Unless there is divine power, human reason is the greatest thing we know of and can possess;

4) So if there are no gods, then we are the greatest beings in the cosmos. In which case, we are the gods.Of course there might be other things we don't know of that are more powerful than we are; or we might (wisely) regard nature as more powerful than we are.

But the most helpful part, I think, is (4), which stands as an invitation to consider who we are as we face the cosmos. We think of ourselves as natural, but we also think of ourselves as standing somehow apart from nature.

So it may be that there is nothing in the cosmos wiser or more clever than we are. We should be honest about this and acknowledge the real possibility that this is the case.

But Chrysippus invites us also to consider the consequences of that belief, since it could be taken as license to act as we will. The danger, as he sees it, is that we might become the sort of people who worship ourselves. This is dangerous in part because it impedes growth; we become like what we worship, and if we worship only ourselves, then we become our own best ideal. I will speak for myself when I say that I, at least, am a cramped and stingy ideal.

Many of the Stoics are content to name nature as god; what matters is that there always be something worth our attention and admiration. I'm reminded of the wise words of David Foster Wallace, who said that

There is no such thing as not worshipping. Everybody worships. The only choice we get is what to worship. And an outstanding reason for choosing some sort of god or spiritual-type thing to worship - be it JC or Allah, be it Yahweh or the Wiccan mother-goddess or the Four Noble Truths or some infrangible set of ethical principles - is that pretty much anything else you worship will eat you alive.You can read the rest of his brief, insightful talk here (or by searching for "This Is Water.")

Wallace comes pretty close to Chrysippus. Neither is trying to convert you to a religion, neither is trying to set the rules for your life, but both are reporting on what they have seen when they have ventured in the direction of denying all the gods: off in that direction, they found they could escape all the gods except the god they then found that they forced themselves to become.

Which, to paraphrase Wallace, is a good reason for choosing to posit some god which, if it existed, would be worth your worship. And then, maybe, to test it by trying to worship it as though it were really there.

∞

As September approaches, people keep asking me, "Are you ready to get back in the classroom?"

As early as middle school I knew I wanted to become a college professor, and I love my job. It is a delight to spend time with young people who are curious, after all.

Years ago, my friend Matt Dickerson pointed out to me that it's also my job to help those who are not curious to see why they should be. As it turns out, that work is usually delightful, too, a rewarding challenge.

So on the whole, I love my work.

But I admit I don't love classrooms, for several reasons:

First, no matter what decade, every classroom I've been in has exhibited an unhealthy tendency towards becoming cluttered with the latest technology, and most of that tech seems to take up a lot of space and to become the center of attention. I'm not opposed to technology in the classroom, not at all. But I'm opposed to letting it get in the way, as it does when the "Smart Cart" leaves me no room for my lecture notes, or when I can't seem to turn the ceiling-mounted projector on or off. I'm a fan of chalk, because chalk allows spontaneity, and it allows for much more than alphanumeric writing in neat rows. Sadly, concerns about chalk dust getting into computers is threatening to make chalkboards disappear from my classrooms. Alas. Chalk is an excellent technology, and if it vanishes, I will mourn its loss.

Second, classroom architecture is not some value-free, neutral design. Classroom architecture makes a big difference in how people teach, and how they learn:

Which is why, as often as I can, I get my students out of the classroom. When we are reading Thoreau's Walking, we go for a walk. When I teach environmental philosophy, we often meet under the great tree in our campus quad, where I encourage students to daydream and to play with the grass, to look for worm-castings and owl pellets, feathers and seed-pods, invertebrates and fallen bits of bark. What good is it to gain the world of theoretical knowledge at the expense of knowledge gained through vital, haptic, bodily experience?

And this is why I am a preacher of the importance of study abroad. Not just travel, but serious, engaged, rigorous study in the classroom of life in another place. This is why I teach Classics in Greece every year, and why year after year I take students to Central America to study environmental philosophy and ecology.

More and more I've been trying to shift the learning focus in my classes from the classroom to the laboratory - where by "laboratory" I mean anywhere that allows students to learn with their whole person. I make my ancient philosophy students devote hours each semester to star-gazing, in part because this is what the ancients did, and in part because I don't want them to miss the stars. I want them to gaze in wonder at the firmament so that when they read Aristotle and Galileo they know that they've looked at what those great minds saw as well. We even occasionally take field trips to really dark places like the South Dakota Badlands so we can see the skies even better.

My environmental philosophy students must observe a square meter of earth for a semester, spending an hour at a time without a camera, drawing and writing about what they see, because it does not make sense to me to talk about the earth when you have not taken the time to sit upon it, to listen to it, to smell and taste it, and to see what other lives creep, and walk, and fly across it.

My friend Aage Jensen advocates the Norwegian philosophy of Friluftsliv, life and education outdoors. And when he organizes a conference on it, he eschews conference centers and holds the conference while walking through the mountains, or paddling a river. Because he believes that one should practice what one preaches, and that nature is always ready to teach.

To paraphrase the Stoic Musonius, teachers would do well to talk less and to take their students with them into the fields, because there they will learn far better and far more than in the lecture hall.

Teaching Outdoors

|

As early as middle school I knew I wanted to become a college professor, and I love my job. It is a delight to spend time with young people who are curious, after all.

Years ago, my friend Matt Dickerson pointed out to me that it's also my job to help those who are not curious to see why they should be. As it turns out, that work is usually delightful, too, a rewarding challenge.

So on the whole, I love my work.

But I admit I don't love classrooms, for several reasons:

First, no matter what decade, every classroom I've been in has exhibited an unhealthy tendency towards becoming cluttered with the latest technology, and most of that tech seems to take up a lot of space and to become the center of attention. I'm not opposed to technology in the classroom, not at all. But I'm opposed to letting it get in the way, as it does when the "Smart Cart" leaves me no room for my lecture notes, or when I can't seem to turn the ceiling-mounted projector on or off. I'm a fan of chalk, because chalk allows spontaneity, and it allows for much more than alphanumeric writing in neat rows. Sadly, concerns about chalk dust getting into computers is threatening to make chalkboards disappear from my classrooms. Alas. Chalk is an excellent technology, and if it vanishes, I will mourn its loss.

Second, classroom architecture is not some value-free, neutral design. Classroom architecture makes a big difference in how people teach, and how they learn:

|

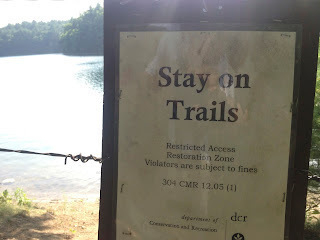

| Step off the trails! Explore! An ironic sign at Walden Pond. |

And this is why I am a preacher of the importance of study abroad. Not just travel, but serious, engaged, rigorous study in the classroom of life in another place. This is why I teach Classics in Greece every year, and why year after year I take students to Central America to study environmental philosophy and ecology.

More and more I've been trying to shift the learning focus in my classes from the classroom to the laboratory - where by "laboratory" I mean anywhere that allows students to learn with their whole person. I make my ancient philosophy students devote hours each semester to star-gazing, in part because this is what the ancients did, and in part because I don't want them to miss the stars. I want them to gaze in wonder at the firmament so that when they read Aristotle and Galileo they know that they've looked at what those great minds saw as well. We even occasionally take field trips to really dark places like the South Dakota Badlands so we can see the skies even better.

My environmental philosophy students must observe a square meter of earth for a semester, spending an hour at a time without a camera, drawing and writing about what they see, because it does not make sense to me to talk about the earth when you have not taken the time to sit upon it, to listen to it, to smell and taste it, and to see what other lives creep, and walk, and fly across it.

My friend Aage Jensen advocates the Norwegian philosophy of Friluftsliv, life and education outdoors. And when he organizes a conference on it, he eschews conference centers and holds the conference while walking through the mountains, or paddling a river. Because he believes that one should practice what one preaches, and that nature is always ready to teach.

To paraphrase the Stoic Musonius, teachers would do well to talk less and to take their students with them into the fields, because there they will learn far better and far more than in the lecture hall.

|

| Nature is full of things worth seeing. |