study abroad

- This too is related to technology, of course. If the class is focused on video screens, then all the chairs will face the screens, and the classroom might even be structured like a theater. Etymologically, "theater" means something like "a place of gazing," and theaters tend to encourage people to gaze. Sometimes this can work against other activities, like colloquy, small-group interaction, and really anything that involves students moving from one place to another.

- If that last sentence made you ask,"But why do you want your students to move from one place to another?" then you see that we have some pretty strong presuppositions about how education should happen: students should sit and listen, teachers should stand and lecture. This communicates something about authority, and at times that's helpful. But it can also invite students to lean back into passivity, and to assume they have no role in their own education.

- The furniture in classrooms tells us how people are to behave, because it has been made and purchased by people who had in mind some idea of how students should behave. Most wrap-around desks are made for right-handed people, for instance. And most classroom desks I've seen expect students to sit upright, at attention, with a book open in front of them. I really don't like those desks, and I feel trapped when I sit in them. I wonder sometimes how they make my students feel. I wish we had fewer chairs and more sofas. Maybe a fireplace, or some tables with glasses of water, and ashtrays on them. I suppose I wish I could teach in pubs or ratskellers, which are, after all, places consciously designed for people to meet and discuss what most matters to them, informally, passionately, amicably.

- Classrooms that privilege video screens tend to undervalue natural light and windows. I am reminded of Emerson's reflection on a boring sermon he once heard. Emerson wrote, in his Divinity School Address, that while the minister droned on, Emerson looked out the window at the falling snow, which, he proclaimed, preached a better sermon than the minister. I have no doubt that nature can often give a better lecture than I can.

How to Make the Most of Studying Abroad

A new short article I've published on Medium, about making the most of re-entry after you've studied abroad. It's the same advice I'd give anyone who has traveled, if they want to keep getting the benefits of travel even after they've returned.

I've written a few other posts about this topic here on Slowperc. You can find them here.

If you want to subscribe to my Medium articles, here's a simple way you can do so. A portion of your subscription fee goes to support my writing, so thanks in advance.

Nature As A Classroom

These are not always easy conditions. Many hard-working Guatemalans live in poverty that is hard to conceive in our country; it is hot and wet except for when it is cold and wet; biting insects are everywhere; disease and snakes and thorny vines like bayal are constant threats.

But it is also a beautiful place with astonishing biodiversity and remarkable people whose resilience and generosity always make me want to improve my own character. They welcome us into their homes and into their lives, and they are glad to see us come to appreciate the place they live.

I expect that my students will forget much of what I say in my lectures and much of what they read in books. But I doubt very much that they will forget the people they have met here. Guatemala has gone from being an abstraction to a concrete reality. When they meet kind people of good character who have walked across Mexico and made it into the USA only to be caught and deported, "illegal immigrants" now have a face, a home, a family at whose table my students have received a nourishing and welcoming meal.

Likewise, they will not likely forget the sound of howler monkeys at night or the experience of scrambling up Maya temples still covered in a thousand years of trees and soil. They won't forget the long walk in a deep green forest and the smells of tortillas and beans cooked over a wood fire.

It is expensive to bring students so far. One could object that the money could be better spent on viewing the forest online or donating it to rainforest conservation. I disagree. I'm not in the business of dispensing information; I'm in the business of transforming lives, and not much transforms like full-bodied experience. Before we leave for Guatemala my students read papers written by wildlife conservation researchers. In Guatemala they meet those researchers in person and get to hear their stories. They hear in their tone and see in their eyes what brought them to Guatemala and what keeps them here. In such times my students go from taking in data to rethinking their lives.

It is my hope - my exuberant, perhaps not wholly rational hope - that out of such lived experience of nature my students will become people who comfort orphans and widows in their distress, who receive the foreigner into their own homes, who marvel and the world's diversity and who, for the rest of their lives, work to preserve it.

Entertaining Angels

Here's an excerpt:

You just never know. There’s no way to know, just from looking at the sign. Maybe he was a con man, or maybe he was just my brother, genuinely in need of human contact to maintain his dignity. Or maybe he was even more than that. How does that passage go? “Some of you have entertained angels unawares.”You can read the rest of it here.

Searching For Winter Strawberries

|

| A late October strawberry in my garden |

One day in February, for no particular reason, I wanted to eat strawberries. A few blocks from my flat there was a market, so I walked there and searched for fruit stands. Finding one but seeing that they had no strawberries, I asked the proprietor, "Do you know where I can find strawberries?"

"Of course," he replied. "Right here."

"But you don't have any," I observed.

"Of course I don't," he said.

I was confused. "But you said I could find strawberries right here."

"You can," he replied. "But not until June."

This took a little while to sink in. I was accustomed to going to a supermarket at home in New York and buying any fruit I wanted at any time of year. Now I was being told what should have been perfectly clear: fruit is seasonal.

At first I was disappointed, but it took only a few minutes before I realized that this wasn't such a bad thing. It meant that the strawberries, when they arrived, would taste that much sweeter. The disappointment of having to wait would be repaid by the delight when they did arrive.

The experience didn't reform me, of course. I love eating my favorite foods year-round, despite not having harvested them and usually without knowing where they came from.

But it did make me appreciate some of the rhythms of life around me. The first part of Aldo Leopold's A Sand County Almanac, and most of Thoreau's Walden - two of my favorite books - follow the cycle of the seasons in the northern part of the United States. Their understanding of nature is one that allows nature to undergo its habitual changes. They might even say that what they know about nature arises from attention to just those changes. Phenology, the attention to when and how things appear and disappear throughout seasons, is one of the most important parts of learning to see the world. If I may speak an Emersonian word, phenology attunes us to the music nature wants us to hear. To speak less mystically, it accustoms us to natural patterns, and much of what the naturalist wants is to learn those patterns so well that we can then see when nature departs from them.

What are the calendars in your life? Technology has made many of them seem unnecessary, but I suspect that they give us much more than we know, just as my experience in Spain gave me unlooked-for lessons. We should be careful not to insist that others delight in the absences or disciplines we delight in; what may be a delightful, self-imposed fast to us may be devastating to someone who is genuinely hungry. When we choose them for ourselves, school calendars, planning one's garden, the liturgical calendars and holidays of the world's religions - each of them can offer us rhythms of both discipline and delight as we make ourselves wait for the strawberries to ripen, the hummingbirds to return, the exams to end, the candles to be lit.

Teaching Outdoors

|

As early as middle school I knew I wanted to become a college professor, and I love my job. It is a delight to spend time with young people who are curious, after all.

Years ago, my friend Matt Dickerson pointed out to me that it's also my job to help those who are not curious to see why they should be. As it turns out, that work is usually delightful, too, a rewarding challenge.

So on the whole, I love my work.

But I admit I don't love classrooms, for several reasons:

First, no matter what decade, every classroom I've been in has exhibited an unhealthy tendency towards becoming cluttered with the latest technology, and most of that tech seems to take up a lot of space and to become the center of attention. I'm not opposed to technology in the classroom, not at all. But I'm opposed to letting it get in the way, as it does when the "Smart Cart" leaves me no room for my lecture notes, or when I can't seem to turn the ceiling-mounted projector on or off. I'm a fan of chalk, because chalk allows spontaneity, and it allows for much more than alphanumeric writing in neat rows. Sadly, concerns about chalk dust getting into computers is threatening to make chalkboards disappear from my classrooms. Alas. Chalk is an excellent technology, and if it vanishes, I will mourn its loss.

Second, classroom architecture is not some value-free, neutral design. Classroom architecture makes a big difference in how people teach, and how they learn:

|

| Step off the trails! Explore! An ironic sign at Walden Pond. |

And this is why I am a preacher of the importance of study abroad. Not just travel, but serious, engaged, rigorous study in the classroom of life in another place. This is why I teach Classics in Greece every year, and why year after year I take students to Central America to study environmental philosophy and ecology.

More and more I've been trying to shift the learning focus in my classes from the classroom to the laboratory - where by "laboratory" I mean anywhere that allows students to learn with their whole person. I make my ancient philosophy students devote hours each semester to star-gazing, in part because this is what the ancients did, and in part because I don't want them to miss the stars. I want them to gaze in wonder at the firmament so that when they read Aristotle and Galileo they know that they've looked at what those great minds saw as well. We even occasionally take field trips to really dark places like the South Dakota Badlands so we can see the skies even better.

My environmental philosophy students must observe a square meter of earth for a semester, spending an hour at a time without a camera, drawing and writing about what they see, because it does not make sense to me to talk about the earth when you have not taken the time to sit upon it, to listen to it, to smell and taste it, and to see what other lives creep, and walk, and fly across it.

My friend Aage Jensen advocates the Norwegian philosophy of Friluftsliv, life and education outdoors. And when he organizes a conference on it, he eschews conference centers and holds the conference while walking through the mountains, or paddling a river. Because he believes that one should practice what one preaches, and that nature is always ready to teach.

To paraphrase the Stoic Musonius, teachers would do well to talk less and to take their students with them into the fields, because there they will learn far better and far more than in the lecture hall.

|

| Nature is full of things worth seeing. |

Bless You!

The Emperor Charles V reportedly said that as many languages as a man knows, that many times over is he a man. I don't know if that's true, but in high school I took courage from it. I was athletic, but lean, with a great build for biking and running, but too slender to be considered dangerously manly. My only formal sports were swimming and ultimate frisbee. I loved skiing and hiking and rock-climbing, but the more I exercised, the leaner I got. There was no chance I'd ever become a star athlete, and I think that realization saved me from trying to become what I was not. Although I didn't know Emerson's writing back then, I nevertheless arrived at an Emersonian conclusion: there are as many kinds of manliness, and courage, as there are men and women to embody them. Emerson puts it like this:

“It is he only who has labor, and the spirit to labor, because courage sees: he is brave, because he sees the omnipotence of that which inspires him. The speculative man, the scholar, is the right hero. Is there only one courage, and one warfare? I cannot manage sword and rifle; can I not therefore be brave? I thought there were as many courages as men. Is an armed man the only hero? Is a man only the breech of a gun, or the hasp of a bowie-knife? Men of thought fail in fighting down malignity, because they wear other armour than their own.”So I threw myself into doing what I was made to do with joy, and to living a brave life in my own way. Some people find learning a foreign language terrifying; I do not. I'm one of those people blessed with an unusual ability to learn foreign languages quickly and with little effort. When I'm around a new language, I listen to its music and its rhythms and make them my own, and I begin to take apart the language as I hear it, so I can think with it, and watch its parts move. And I ask a lot of questions: How do you say this in your language? What does this mean? When do you say that?– R.W. Emerson, Commencement Address given at Middlebury College on July 22, 1845, in Emerson At Middlebury College, Robert Buckeye, ed. (Middlebury, Vermont: Friends of the Middlebury College Library, 1999), p. 39.

This turns out to be a good way to learn one's own language, too. Not everything can be translated, and when you find something in your native tongue that's hard to say in another language, you've found something that is a unique possession of the speakers of your language. Or when you learn that one word in your language takes many forms in another language, you begin to see how your cultural heritage has come equipped with some blind spots. The same is true of grammar, of inflection, of syntax, and so on.

So learning another language is not simply a matter of replacing one vocabulary with another. Learning a language means learning a culture, a history, a literature.

(This is why language-learning software can help, but it's not enough, and it's no substitute for excellent teachers and for studying abroad.)

In middle school, as I was trying to actualize all my potential and to become as many men as I could be, I spent a lot of time learning basic phrases and grammar in other languages. How do you greet someone in this language? How do you say goodbye? How do you ask for what you want? These tend to be fairly straightforward in the languages I studied.

But some phrases were harder. How do you say "Please"? That word is, after all, a contraction of a whole clause, "If it please you," with a subjunctive verb. It's not like a name for an object or a place, which might be easily translated; it's a way of calling on a whole tradition of regarding the wishes of others as important - or at least, of pretending to honor those wishes. Now, most of the languages I studied had simple ways of saying "please," but along the way I discovered that not all English speakers consider "please" to be correct. Some religious communities, for instance, regard such words as unnecessary; we should be willing to give what we're asked for without demanding that the other regard our wishes as important, they reason.

|

| Modern saints at Westminster Abbey; Their stories are a blessing. |

When I first met my frosh college roommate, Nick, he sneezed. I said the customary thing: "Bless you!" He looked at me oddly, and didn't say anything. Over the coming weeks, I repeated the phrase each time he sneezed. Finally, he asked me "Why do you keep saying that?" I realized I hadn't any better answer than to say that's what I heard others do. His question got me wondering why we acknowledge sneezes.

After all, we don't say something to accompany other bodily functions, do we? Is there a stock phrase for hiccups, or burps? For a rumbling belly? A cough? A yawn?

Over the years, it started to bother me that others felt the need to comment on my sneezes. When I ask people why they do it, I usually get some lame reply about how it's because long ago people believed that sneezes were a sign of some dangerous spiritual or physical ailment; or that it had to do with fear of the Black Plague; or that it was a response to the fear that sneezes were signs of demonic possession; and in any case, sneezes needed to be countered with blessings.

Okay, fine. I'll let the Middle Ages off the hook next time they bless my sneezing. But why do YOU do it? The answer seems to be cultural habit. It's not a necessity of nature, but something we've made ourselves do until we've forgotten why we do it. It's a thoughtless reflex, and I think this is what annoys me.

Now, after years of being a curmudgeon and a grouch about this, I'm starting to reconsider my objection to these responses to my sternutations. On the one hand, these blessings are thoughtless, and they demand a reply of "thank you" when frankly, I'm still recovering from a sneeze and would rather not say anything. On the other hand, perhaps we shouldn't want fewer blessings in our lives, but more of them, or at least more sincere ones.

As I think back over my life, I've received these blessings often from strangers on a bus or a subway, or in a park in a foreign city. People who do not know me stop their activity to speak a word of blessing into my life, to look me in the eye and put into simple words their wishes for my good health.

Speaking does not make things so, not instantly, anyway. But putting things into words is nevertheless very powerful. I'm not talking magic here; I'm talking about the way our words affect ourselves and others. Naming is powerful. When our inarticulate anger or frustration evolves into naming someone as the one who needs to be punished, the person becomes a criminal, something less than a person. The greater the crime, the lesser the human. Because naming is powerful, cursing is powerful. Which is why I taught my kids that it's not words that are bad, but the uses of words.

And if history teaches us anything at all, it shows us how easy we find it to curse others, to come up with simple, curt, dehumanizing names for entire classes of others. We find it easy not to look others in the eye but to look no further than the skin, or to look through others as though they were not there. We find it easy to curse those who live across borders of towns and nations, those who drive in front of us or behind us, those whose faces we never see and whom we know only through a few words we've read online.

In light of that, I suppose that if you want to bless me--indeed, if you find it hard not to bless me--that should be a welcome thing. Just give me a minute to recover from my sneeze before I thank you. And may you be blessed, too.

"Life Is Our Dictionary"

R.W. Emerson, "The American Scholar"

Re-entry: Bringing It Home After Studying Abroad

Now let me offer one more step that will make re-entry even more valuable for you. As you journal and reflect on what you saw while you were abroad, take time to look over your journal entries, and ask yourself, What do I want to bring home?

|

| What will you bring home? |

Charles Peirce once wrote, "An American who has never been abroad fails to perceive the characteristics of Americans." Now you've been abroad, and you see things differently. Make your new vision matter. Is there one lesson you can incorporate into your life? One thing you saw abroad that you wish you could have here?

When I've lived in Europe, I've never needed a car, but here in the U.S. I often feel I need to drive even when I'm not going very far. So I've decided to try to walk or bike whenever I can, and to use public transit. It's a small thing, but it makes a big difference for my health, and it might make a difference in the lives of others around me. This is one thing I've brought home.

So how about you? What did you learn? What do you see differently? And what will you bring home?

When You Come Home From Studying Abroad

|

| Epidauros |

We think that when Americans study abroad, that's good for the whole world because it helps Americans to see America as they could not see it otherwise.

Of course, it's not without its costs. Our students who have just come back are jetlagged and road-weary. Many are a little deeper in debt. And the new term is about to begin.

That being the case, let me offer some advice to those of you who are returning from studies abroad. I know you're tired, so I'll be brief:

1) Get some rest. Stay up until it's dark out, and then sleep deeply. Get back in sync with the sun on this side of the world.

2) Journal every day. Trust me. Do this. Do it now. Don't put it off. Your memories are already fading. Get it down. Write however you want - impressionistically, narratively, whatever. Write about all five senses. Write about language. Write about the people you were with, and write their names down. Write down names of places, hotels, restaurants, museums. Do it now. Go.

3) Tell stories. To anyone who will listen. Storytelling is one of our oldest and best ways of sharing our experiences. Enrich your classmates and professors who couldn't join you. Tell us what you saw, what surprised you. Tell us anecdotes about specific times, places, meals, people, vehicles. Give us detail. As you do, you will nourish your own memories, and you'll sort out what matters most to you. As Umberto Eco once wrote,

"One who tells stories must have another to whom he tells them, and only thus can he tell them to himself."*And perhaps most importantly,

4) Come up with a couple of one-liners. This is how to prepare for the inevitable question, "How was India?" If you say "It was amazing!" the conversation is over and the opportunity is gone. Instead, try something like "I never had food like the food I had in Delhi!" or "I wish you could have seen the quality of the rivers" or "The best day was the fourth day." If the questioner was just being polite, that will satisfy them. But these specific memories, offered as one-liners, are invitations to further conversation. They are a way of saying "Would you like to know more?"

You had a great experience. Some of it was wonderful, some was no doubt very difficult. This is why we go. Now, you've brought it home. Do what you can to preserve the memories, and to share them with the rest of us.

So welcome home! And now, go get some sleep. (And then you can read Part Two of this post.)

|

| My mother in Rome during her college years. |

On Traveling and Journaling

This probably sounds like a dream life, and I have to admit it's not all that bad.

But it's also a lot of work. A weeklong class in Greece usually takes me a little over a year to prepare, and in the semester leading up to it the workload approaches the amount of preparation I do for any of my other classes. Last fall I was teaching my usual load plus prepping two study-abroad courses, so I was swamped much of the time.

But it's worth it. My students come back with perspectives they could not have gained at home, if their journals are to be believed.

I always require my students to keep a journal while we're traveling. Sometimes I ask them specific questions, but usually I tell them to journal not for me but for themselves. You may think this naive, and you may be right. But I'd rather be naive than cynical. That is, I'd rather appeal to their self-interest and to their own sense of themselves as growing learners than force them to write answers to my pre-fab questions.

I do give them some guidance, however. Here are some of the things I teach them about journaling:

1) Pay attention to the little things, and write down whatever catches your attention. If you noticed it, it probably matters.

2) Pay attention to all of your senses. We tend to write about major events that happened, as though we were news reporters looking for the big story. But why not write about the smells? What sounds do you hear? What do the birds or the streets or the nighttimes sound like? How does the place you're in feel on your skin? What new tastes have you encountered? And so on.

3) Write continuously. Don't plan to write a sketch or outline and then fill it in later. As soon as you are on that plane home you will begin to forget what you experienced, and you will forget far more quickly than you want to believe. Write now.

4) Write "gestures" and impressions. Some of us have very good prose composition skills, and some of us do not. But all of us can write down a few phrases, a few adjectives, a few words we've heard in passing. Why not include entries in which you stand in one place and write down a list of nouns, of verbs, of adjectives that strike you as you soak the place in?

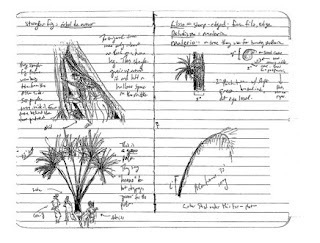

5) Draw pictures. This is one of the best pieces of advice I've ever received, and I am no artist. Cameras are great, but they capture what they see. Drawing captures what you see. Drawing also forces you to see what you wouldn't have seen otherwise. As Louis Agassiz once said, a pencil is one of the best tools for seeing. One of the best drawing tools I know of is a cheap ball-point pen. You don't need fancy paper, and you don't need a lot of time. Most of my best journal drawings are made in under two minutes with a cheap pen.

Try this out, and see if it doesn't completely change your journals. When I'm in Greece, I like to show my students the different kinds of stonework in ancient walls. The kind of stonework is helpful for dating the site, and it tells us a lot about the technology of the people who built the walls. I've found that as I try to draw a section of wall, the differences between cyclopean walls, Lesbian walls, and Roman walls become clearer to me, I remember them better, and I am better able to teach about them.

6) Revisit your journal periodically. Last of all, when you get back, revisit your journal from time to time. Start off doing so every week, and then every month and every year. When you revisit it, add a page or two of notes. What does your experience traveling back then mean to you now? Traveling is a luxury some of us enjoy, but it can also be a valuable learning opportunity, one that continues to be valuable for as long as we continue to reflect on it.

Do you have other journaling tips? I'd love to hear them. Meanwhile, I've got to get back to preparing for my next trips and courses abroad.

Buen viaje!