tattoos

∞

That word incidentes bothered me, though, as did the genitive plural gigantium. Now, I am more of a Hellenist than a Latinist, so if you spot any errors in what I say here, I would be grateful for your corrections. Gigas is a loan word from Greek, which might explain the two different genitive plurals, Gigantum being correct, but Gigantium appearing to follow the rules. Incidentes just sounds funny, as though the dwarves had fallen upon the Giants - though it could indicate that the dwarves were fortunate enough to stumble upon the Giants; incido can have that meaning, after all. But another text I have found has insidentes, which makes more sense to me, meaning "sitting upon" or "standing upon."

As I said in my previous post, I am reluctant to take the responsibility for others' tattoos, but I have tentatively suggested that

Standing on the Shoulders of Giants

After writing my previous post about tattoos in ancient languages, a former student reminded me that I also helped her track down a Latin text she wanted to have inked. She

wanted to use the phrase found in one of Newton's letters to Hooke, "If I

have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants." This

is a funny phrase, one that gets repeated a lot and that has a number of

variants. For example, Didacus Stella writes (In Luc. 10 tom. 2)

Pygmaei Gigantum humeris impositi plusquam ipsi gigantes vident

("Pygmies,

placed on the shoulders of Giants, see further than the Giants

themselves." See footnote 20 of Alexandre Koyré's "An Unpublished

Letter of Robert Hooke to Isaac Newton," Isis, Vol 43, No. 4 (Dec., 1952), pp312-33, U of Chicago Press.)

It's a funny phrase because it can be used both boastfully and self-deprecatingly. Newton, in his letter to Hooke, for instance, seems to boast that he sees farther than Hooke, but that he does so as a dwarf.

It also appears in Bernard of Chartres, quoted by John of Salisbury in his Metalogicon. One source I found has John saying this:

("Bernard of Chartres used to say that we are like dwarves, incidentes on the shoulders of giants, so that we might see more than they, and things further off...")Dicebat Bernardus Carnotensis nos esse quasi nanos, gigantium humeris incidentes, ut possimus plura eis et remotiora videre, non utique proprii visus acumine, aut eminentia corporis, sed quia in altum subvehimur et extollimur magnitudine gigantea. Et his facile acquieverim, quia artis praeparatitia et multos articulos veritatis tradunt artium praeceptores, etiam in introductionibus suis, aeque bene antiquis, et forte commodius.

That word incidentes bothered me, though, as did the genitive plural gigantium. Now, I am more of a Hellenist than a Latinist, so if you spot any errors in what I say here, I would be grateful for your corrections. Gigas is a loan word from Greek, which might explain the two different genitive plurals, Gigantum being correct, but Gigantium appearing to follow the rules. Incidentes just sounds funny, as though the dwarves had fallen upon the Giants - though it could indicate that the dwarves were fortunate enough to stumble upon the Giants; incido can have that meaning, after all. But another text I have found has insidentes, which makes more sense to me, meaning "sitting upon" or "standing upon."

As I said in my previous post, I am reluctant to take the responsibility for others' tattoos, but I have tentatively suggested that

NANI GIGANTUM HUMERIS INSIDENTESmight fit the bill for her, "Dwarves standing upon the shoulders of giants." If your Latin is better than mine, I welcome your corrections, especially before she makes this a permanent part of her skin.

</div>

∞

Written On The Skin

One of the peculiar things about teaching Greek and knowing several other ancient languages is that people often come to me seeking help with tattoos.

A few years ago a student named Brian came to me and asked "How do you say 'Suck Less' in Greek?" Apparently this was a phrase that his running coach said to his team to inspire them to run better.

As crude as the phrase is, I was intrigued by the problem of translation. "In order to translate the phrase I'd have to know what you mean by it," I replied. I spent a little while explaining how it would be possible to say, for instance, that an infant should nurse less; or that one should inhale less strongly. Or, if you pursue the more colloquial usage of the verb "suck," you might decide that it refers to poor behavior or - ahem - to a kind of erotic pleasure-giving in which the giver is thought to be demeaned by the giving.

Eventually I made the case that if you want to say it in Classical Greek, it would make sense to say it in a way that attended to the use of words in that language, and pointed him to Plutarch's Sayings of Spartan Women as a source of pithy sayings about living and acting strenuously. Ever since I took my first Greek class with Eve Adler at Middlebury College years ago, I've liked the phrase η ταν η επι τας, (at the link above, see #16 under "Other Spartan Women"; click on the Greek flag to see the full Greek text) which is often translated "Come back with your shield or upon it," meaning "Act virtuously in battle; either die with your weapons or win with your weapons, but do not throw them away in order to win your life at the expense of your virtue." I like the Greek phrase for its Laconian pithiness.

Of course, that one didn't quite make sense for a runner, so I showed him another from the same collection, κατα βημα της αρετης μεμνησο, or "With every step, remember [your] virtue." ("Virtue" is not a perfect translation; you could translate it as "excellence" also.)

Three years have passed since that conversation with Brian, but a few months ago he tracked me down and showed me his tattoo, which I rather like:

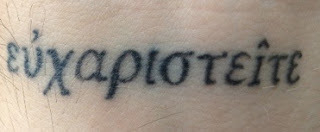

In a new twist, last year another student asked me to help him find the Greek verb "give thanks" as it appears in I Thessalonians 5.18. He didn't tell me what he planned to do with it, but when I saw him later that year at a wedding he showed me this, which he has tattooed on his wrist:

The word you see is ευχαριστειτε, related to our word "Eucharist" and the modern Greek ευχαριστω, meaning "I thank you."

I say this is a "new twist" because at least one passage in the Hebrew scriptures (Leviticus 19.28) appears to prohibit tattooing one's skin. Getting a tattoo, and in particular getting a tattoo of scripture, offers a bit of insight into one's hermeneutics. If the Gospels prohibited tattoos, I doubt many Christians would get them, but since the prohibition comes in the Hebrew scriptures, and since it seems to be tied to particular practices of worship or enslavement that no longer seem relevant, many young Christians are untroubled by it.

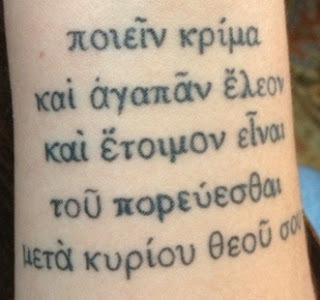

Recently one of my advisees showed me one of several tattoos she has recently acquired. This one is a longer Biblical text, from the prophet Micah, chapter 6, verse 8. I thought it interesting that she chose to get the Septuagint Greek rather than the Hebrew. She knows and translates Biblical (Koine) Greek and so I suppose she felt closer to that language. The text below means "...to do justice and to love mercy and to be ready/zealous to walk humbly with the Lord your God."

I like that verse quite a lot. If you don't know it, it begins by saying that this is what God asks of people. It's the sort of description that makes religion sound less like a burden and more like a description of a life well-lived.

I'm always reluctant to give advice about tattoos, because they're so permanent and so personal. And when I do give advice, I always want to write footnotes about regional dialects and historical and textual variants, or about the difficulties of translation. Quotes out of their native context so often seem lonely to me - such is my academic habit, of always seeing texts as living and moving and having their being* in nests and webs of other texts. Perhaps that's why I've never been inked myself, and I doubt I ever will get a "tat." I'm just not confident I've found words or an image that I'd want written on me forever. Sometimes that feels virtuous because it's prudent; other times I wonder if that's not a moral failing on my part, like I should be willing to commit to something. But I think for now I will remain uninked, and will continue to admire the commitments of my students.

* For example: I am borrowing this phrase ("live and move and have their being") from St Paul in Acts 17.28; he, in turn, appears to be borrowing it from Epimenides, who writes Εν αυτω γαρ ζωμεν και κινουμεθα και εσμεν. The phrase winds up being used in a number of other places, having been so eloquently translated into English by the King James Version of the Bible. See, for example, its use in the Book of Common Prayer, and in the first line of the hymn "We Come O Christ To Thee."

A few years ago a student named Brian came to me and asked "How do you say 'Suck Less' in Greek?" Apparently this was a phrase that his running coach said to his team to inspire them to run better.

As crude as the phrase is, I was intrigued by the problem of translation. "In order to translate the phrase I'd have to know what you mean by it," I replied. I spent a little while explaining how it would be possible to say, for instance, that an infant should nurse less; or that one should inhale less strongly. Or, if you pursue the more colloquial usage of the verb "suck," you might decide that it refers to poor behavior or - ahem - to a kind of erotic pleasure-giving in which the giver is thought to be demeaned by the giving.

Eventually I made the case that if you want to say it in Classical Greek, it would make sense to say it in a way that attended to the use of words in that language, and pointed him to Plutarch's Sayings of Spartan Women as a source of pithy sayings about living and acting strenuously. Ever since I took my first Greek class with Eve Adler at Middlebury College years ago, I've liked the phrase η ταν η επι τας, (at the link above, see #16 under "Other Spartan Women"; click on the Greek flag to see the full Greek text) which is often translated "Come back with your shield or upon it," meaning "Act virtuously in battle; either die with your weapons or win with your weapons, but do not throw them away in order to win your life at the expense of your virtue." I like the Greek phrase for its Laconian pithiness.

Of course, that one didn't quite make sense for a runner, so I showed him another from the same collection, κατα βημα της αρετης μεμνησο, or "With every step, remember [your] virtue." ("Virtue" is not a perfect translation; you could translate it as "excellence" also.)

Three years have passed since that conversation with Brian, but a few months ago he tracked me down and showed me his tattoo, which I rather like:

In a new twist, last year another student asked me to help him find the Greek verb "give thanks" as it appears in I Thessalonians 5.18. He didn't tell me what he planned to do with it, but when I saw him later that year at a wedding he showed me this, which he has tattooed on his wrist:

The word you see is ευχαριστειτε, related to our word "Eucharist" and the modern Greek ευχαριστω, meaning "I thank you."

I say this is a "new twist" because at least one passage in the Hebrew scriptures (Leviticus 19.28) appears to prohibit tattooing one's skin. Getting a tattoo, and in particular getting a tattoo of scripture, offers a bit of insight into one's hermeneutics. If the Gospels prohibited tattoos, I doubt many Christians would get them, but since the prohibition comes in the Hebrew scriptures, and since it seems to be tied to particular practices of worship or enslavement that no longer seem relevant, many young Christians are untroubled by it.

Recently one of my advisees showed me one of several tattoos she has recently acquired. This one is a longer Biblical text, from the prophet Micah, chapter 6, verse 8. I thought it interesting that she chose to get the Septuagint Greek rather than the Hebrew. She knows and translates Biblical (Koine) Greek and so I suppose she felt closer to that language. The text below means "...to do justice and to love mercy and to be ready/zealous to walk humbly with the Lord your God."

I like that verse quite a lot. If you don't know it, it begins by saying that this is what God asks of people. It's the sort of description that makes religion sound less like a burden and more like a description of a life well-lived.

I'm always reluctant to give advice about tattoos, because they're so permanent and so personal. And when I do give advice, I always want to write footnotes about regional dialects and historical and textual variants, or about the difficulties of translation. Quotes out of their native context so often seem lonely to me - such is my academic habit, of always seeing texts as living and moving and having their being* in nests and webs of other texts. Perhaps that's why I've never been inked myself, and I doubt I ever will get a "tat." I'm just not confident I've found words or an image that I'd want written on me forever. Sometimes that feels virtuous because it's prudent; other times I wonder if that's not a moral failing on my part, like I should be willing to commit to something. But I think for now I will remain uninked, and will continue to admire the commitments of my students.

*****

* For example: I am borrowing this phrase ("live and move and have their being") from St Paul in Acts 17.28; he, in turn, appears to be borrowing it from Epimenides, who writes Εν αυτω γαρ ζωμεν και κινουμεθα και εσμεν. The phrase winds up being used in a number of other places, having been so eloquently translated into English by the King James Version of the Bible. See, for example, its use in the Book of Common Prayer, and in the first line of the hymn "We Come O Christ To Thee."

*****

Update: a week or so after posting this I ran into the mother of one of the people whose tattoos are shown above. She thanked me, though I am not sure whether she was thanking me for helping her son get a tattoo, or for helping him to get the grammar right.