teaching

Why All Saints’ Day Matters To Me

Here's a bit from a recent post I wrote and shared on Medium:

Who knows? The student in my classroom, the driver in that other car, the man sleeping on a park bench, the Uber driver, the cashier at the grocery — any one of them might be an angel in disguise.

And similarly, any one of them might some day be considered a saint.

So this All Saints’ Day, I want to remember that.

You can read the whole post for free here.

John T. Meyer Interviews Me On His Leadmore Podcast

John T. Meyer, CEO of Lemonly, is one of the best interviewers I've known. In his Leadmore podcast he has interviewed immigration lawyer Taneeza Islam, Governor Dennis Daugaard, Augustana University President Stephanie Herseth Sandlin, Vaney Hariri, epidemiologist Dr. Lon Kightlinger, and a number of other leaders.

I'm delighted to have joined him in this conversation about teaching as a kind of leadership; ancestral languages; and the value of learning what some might call "unnecessary" knowledge like the liberal arts.

You can find it wherever you get podcasts. You can also find it as a video here.

Gracias, señora Orza

One day when I was in middle school in New York you said to me “You’re good at languages. You should go to Middlebury.” I hadn’t heard of it before, and I had been planning to attend the cheapest local college I could attend, to save my family the cost of college. Then you handed me a brochure from Middlebury, about their summer language programs. A year later, when I was leaving to work in Nepal for the summer, you gave me a blank journal as a parting gift, reminding me that writing matters.

I haven’t seen you since then, and I haven’t been able to track you down to thank you in person, so I’m firing this out into the internet to say thank you to you and to all the other teachers like you. Why? Because you changed my life.

Three years after I last saw you, I drove to Middlebury to check it out, and I fell in love with the place. I sat in on a Religion class (a subject I thought I wouldn't find interesting at all) and learned more about religion in that single hour than I thought possible.

So I applied, and I got in, with a scholarship. I guess they thought I should go there, too! Over the next four years that college made it possible for me to study in Spain; to learn to read and translate multiple forms of classical Greek; to be exposed to history as more than names and dates; to study physics, and math, philosophy, and even a little more religion.

Looking back on those years now, I see that my whole career has arisen out of classes I took there.

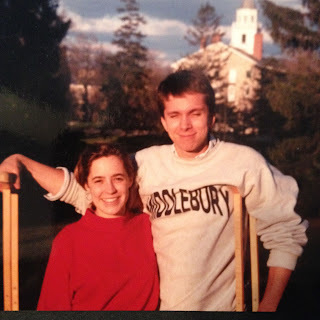

And best of all, I met this amazing woman! I think you’d like her. Like you, she’s smart and sweet. Like you, she encourages me to keep learning. And like you, she’s fluent in Spanish.

|

| We started dating in college, and we're still dating each other now, even though we're both married. I think you'd like her. |

Far more than the classes, she has changed my life. So often it's the people you meet--and not just the things you learn--that change you. I'm grateful to have met you both.

So thanks for being a Spanish teacher in a middle school in rural New York. Thanks for putting up with all of us kids in your classes, year after year. And thanks for taking my future seriously enough that you thought that my life, my travels, and my studies really mattered. You saw all that far more clearly than I did back then, but over the years I’ve come to see what you saw, and I’m forever grateful.

Your loving student,

Dave

South Fork, Eagle River

The houses here are ugly. Taken on their own, any one of them is a beautiful building. Plainly this is spendy real estate in God’s country. But the houses look like they were lifted from the pages of some little-boxes-full-of-ticky-tacky architectural lust propaganda and carpet-bombed on the hillside, then allowed to remain wherever they fell. There is no order, no sense that the houses were built for the place. Every one of them is a garish, angular excrescence on the opposite hillside. No doubt their inmates would disagree with my assessment; they only see the houses up close, and from the inside. They must have no idea how out of place their unnatural rectangles look against the sweeping slope of the Chugach Range. No doubt, when you’re on the other side of those big plates of glass, gazing over here at the state park over your morning K-cup, the view is precious. But when you’re in the state park, looking back, there is nothing on the opposite hillside to love. Over here, there is only regret that these people believed that you could buy both the land and the landscape.

It’s about three miles’ hike in to first bridge in state park. A fairly easy up-and-down walk. It’s raining. Spitting, really, what they call chipichipi in Guatemala, a constant drizzle. The sky is a palette of cottony grays that have lowered themselves onto the mountaintops. There is a clear line below which the mountains are visible. Above it, clouds roll and shift.

I shiver a little in my heavy raincoat and think about putting on my rain pants, but I know I’ll be too hot if I do. Some of my students are wearing shorts.

At the footbridge we sit and eat our lunches. The university has packed us red delicious apples (a mendacious name), bags of honey Dijon potato chips, and turkey sandwiches with lettuce and onions. It’s not good turkey, but no one cares. This is a lovely place. We have other food in this place.

The river is only fifteen feet wide here, and it is the color of chalk, like diluted Milk of Magnesia. Taking off my shoes, I wade in. Immediately my feet start to ache with cold. Turning over a stone, I look at its underside. The gray water drips off and a tiny larva wriggles to get out of the light. It's too small to identify it, maybe a miniscule stonefly. A huge blue dragonfly cruises over the river, darting past me.

There are lots of wildflowers up here. One of my students is on the ground with her laminated guidebook, puzzling over one specimen. I've been carrying these guides everywhere, but they're only helpful for about seventy-five percent of the common stuff. There's just too much life here to get it all in a book.

The flowers grow in so many colors, so many strategies for getting the scarce pollinators' attention in the brief summer. Yellows, purples, and blues predominate. The guidebook warns me about several of the purples: DO NOT EAT THIS! Some of them are poisonous. So are a few of the yellows. This is a beautiful place, but it's also a harsh place, and life clings to the edge. Poison is one good way not to get eaten, I suppose. Looking up the mountain, the trees give way to shrubs a hundred yards above us. A hundred yards more and there's only grass. Above that, I can only see rock.

Some of these plants have another strategy: rather than avoiding getting eaten, they invite it. Berries are the way some plants make use of animals to carry their seeds to new places. Bear scat, full of seeds, is all along the trails here. Each mound is a nursery where some new plant may grow in the fertile dung.

There is a kind of berry like a blueberry that grows on something that looks like a mix between evergreens and moss, only a few inches high. Some people call it "mossberry," appropriately. Some locals call it a blackberry. Matt tells us they're crowberries, as he gathers a handful. He eats some and then the students tentatively pick and eat some too.

We spend three hours there at the bridge, observing. There's so much to see. Some of us write, some draw, some stare at the peaks that surround us. A few doze off. I get out my watercolors and try to paint the landscape, but I'm quickly frustrated. There are so many greens and grays and blues, and I'm no good at mixing colors. I keep painting anyway. I can at least try to get the shapes right, I think, but I'm wrong about that, too. The mountains are stacked up in layers, and the lines look clean and clear at first, but when I try to focus on them they blur into one another. The hanging glacier at the end of the valley looms over us, silent and white and yet so eloquent. The glaciers are what made all of this, and even though they have retreated, the river runs with their tillage, the plants grow in their finely ground dust, the smooth slopes were ground smooth by millennia of ice.

Upstream, Brenden hooks his first-ever dolly varden. This is his first fish in Alaska. He is positively glowing with delight. He cradles it in his hand and then quickly returns it to the water pausing only to admire this vibrant glacial relic of a char. It too depends on the glacier.

The temperature is constantly shifting as the sun comes in and out of the clouds. Each part of the valley takes its turn being illuminated: the river shines like silver; the mountainside glows bright green and the rocks and bushes above the tree line cast sharp shadows; high in the valley small glaciers are bright ribbons streaking the blue granite. The clouds push the sunlight in ribbons across the valley. When we are suddenly in the light, we are warm.

After a few hours we walk back to the car. No one wants to go. For a while we drive in luminous silence.

So, How's The Sabbatical Going?

Sabbaticals and Long Service Leaves

|

| Sabbaticals can be seasons of letting dry husks bear new life. |

Most jobs in the United States don't offer sabbaticals, but I'm fortunate enough to have one that does. Sometimes my kids chide me for choosing a job with relatively low pay, but self-regulated time is something money can't easily buy. I think I chose my career pretty well.

I say "self-regulated time" because my sabbatical isn't early retirement or a long vacation. My job as a college professor has three basic components: teaching, scholarship, and service. A sabbatical frees me from the first of those components, and from parts of the third. More precisely, it frees me from the daily tasks of teaching and service, but I expect that at the end of this year I will be a better teacher because I've had time to do research and to tear down and rebuild some of my classes. And any college capable of taking the long view knows that faculty who take sabbaticals can render better service over the long haul.

What I've been doing

To the casual observer it probably looks like I've spent a lot of time in coffee shops and airports, and not much else. For the last three years I've devoted myself to teaching and service, giving only a little of my time to scholarship. So when I began my sabbatical my scholarly life felt like deep waters pent up behind a strained dam. Over the last few years I've sketched out five books and seven articles and book chapters. Over my sabbatical I hoped to get maybe one book and a couple of articles done. That may not sound like much, but it's fairly ambitious, given how much time it takes to do the research and to write well.

Since my job description breaks down into the three parts I mentioned above, let me say a few words about what I've been doing this year in each of those areas.

Writing: As for academic writing, so far, I've completed one book (on brook trout), and made significant progress on two others (both on the philosophy of religion). Once I get them done, books four and five are ready to go, too. I've submitted one book chapter for someone else's book, and I'm about to submit another. I've written a few book reviews for popular and scholarly journals, too. Last week I gave a lecture at the College of William and Mary on war and evil. Now I'm preparing that lecture for publication as a journal article. By the time this sabbatical is over, I hope to have at least one book under contract and two more articles sent off for review. I've also done some more popular writing, including a couple of articles on virtue ethics in the Chronicle of Higher Education's Chronicle Review - one on guns and one on the ethics of drones or UAVs. Perhaps most importantly, I've been writing every day. As you can see, I've been trying to write quickly here on this blog a couple of times a week, and I've been writing in a lot of other places as well. Like any other skill, it comes more fluidly with practice.

| ||

| Snail shells grow by slow accumulation, as habits do. |

Service: Even though I'm away from campus, my heart is still there. Everything I do as a professor winds up leaning back towards the classroom, which means towards my students. Nothing I do matters more than the people I do it with and for, I think. I must have written sixty letters of recommendation for students this year (which is more time-intensive than one might think). Sabbatical has also given me the chance to help some colleagues here and at other universities. I've been helping half a dozen friends who teach Classics, Philosophy, and Biology at other universities by reading and commenting on drafts of their essays and books. And I've done a lot of "double-blind" reviewing for six or seven academic publishers who want advice on whether to publish certain books or journal articles. Best of all has been time to collaborate with colleagues in far-off places, corresponding with professors and graduate students around the world about philosophy, ecology, Scriptural Reasoning, Henry Bugbee, Charles Peirce, C.S. Lewis, and other matters close to my heart. I list this as "service" but I could just as well call it "ways I've learned from other people far away."

|

| The license plate on the rental car I had at a recent conference. |

Yes. The word "sabbatical" has its roots in a Hebrew word, shabbath, meaning "to rest." It would be a shame not to use the time to get some rest. Last summer I spent two weeks in a writing retreat sponsored by Oregon State at their Shotpouch Creek Cabin with my friend and co-author Matthew Dickerson. We were working, but what restful work it can be to live, think, and write quietly with a friend. We spent half of each day writing, and the other half talking, hiking, fishing, wading in the ocean. We borrowed some hymnals from an Episcopal church in Eugene and spent part of each evening singing as the sun declined behind the coastal range.

On my way to Oregon, I drove my sons to the coast last summer to look at colleges, to go whale-watching, and to watch some professional soccer matches. When I got home to Sioux Falls, I joined a gym and I became my son's rec league soccer coach. This is his last year of living at home with us, and I can't tell you how grateful I am to have this time with him before adulthood takes him off on the next leg of his life's journey. Despite all the work, and travel, and writing, I've had more time with my wife and my kids, and more time for self-care. I feel much healthier and fitter now than I did a year ago. I have a feeling my family is better off for that, too.

I wish everyone, regardless of their line of work, could have an experience like this every few years. It might remind us all what matters. It's expensive, I know. I took a hefty pay cut from an already modest salary to have this year off, and thankfully our savings have been enough to get us through. (And writing and lecturing makes me a few extra ducats to send to my daughter in college from time to time or to spend on my boys at home.)

No doubt some people will read this and wonder why my college is willing to pay me anything at all when I'm not showing up to work. The answer is that some colleges still take the long view. You have to put aside your monthly planner and get a calendar that measures time and value "not by the times but by the eternities" (pace Thoreau), that looks down the years the way a carpenter holds a plank to her eye and looks down the full length of the board rather than seeing only the grain of what is nearest. Money has been spent on me this year by people who thought it worthwhile to let me stretch from my cramped pose. They have let me drink from distant streams so that I can come back nourished not just by the Big Sioux and the Missouri but by the waters of Oregon and New York and Virginia - and in some sense by the Hippocrene itself.

So that's what I've been doing. I'm sorry I haven't been around campus much. In the long run, what I've been doing should make my return to campus a very good one indeed. I can't wait to tell you more about what I've learned this year once I return.