technology

- This too is related to technology, of course. If the class is focused on video screens, then all the chairs will face the screens, and the classroom might even be structured like a theater. Etymologically, "theater" means something like "a place of gazing," and theaters tend to encourage people to gaze. Sometimes this can work against other activities, like colloquy, small-group interaction, and really anything that involves students moving from one place to another.

- If that last sentence made you ask,"But why do you want your students to move from one place to another?" then you see that we have some pretty strong presuppositions about how education should happen: students should sit and listen, teachers should stand and lecture. This communicates something about authority, and at times that's helpful. But it can also invite students to lean back into passivity, and to assume they have no role in their own education.

- The furniture in classrooms tells us how people are to behave, because it has been made and purchased by people who had in mind some idea of how students should behave. Most wrap-around desks are made for right-handed people, for instance. And most classroom desks I've seen expect students to sit upright, at attention, with a book open in front of them. I really don't like those desks, and I feel trapped when I sit in them. I wonder sometimes how they make my students feel. I wish we had fewer chairs and more sofas. Maybe a fireplace, or some tables with glasses of water, and ashtrays on them. I suppose I wish I could teach in pubs or ratskellers, which are, after all, places consciously designed for people to meet and discuss what most matters to them, informally, passionately, amicably.

- Classrooms that privilege video screens tend to undervalue natural light and windows. I am reminded of Emerson's reflection on a boring sermon he once heard. Emerson wrote, in his Divinity School Address, that while the minister droned on, Emerson looked out the window at the falling snow, which, he proclaimed, preached a better sermon than the minister. I have no doubt that nature can often give a better lecture than I can.

∞

A Short Story: Mercy

For several years friends have been urging me to write a novel during the month of November as part of the NaNoWriMo movement, but I rarely have the time or motivation. Instead, today I have taken ten minutes to sketch out a picture of a short story, remembering that good stories have begun with less than this.

When we left the Earth we thought we had escaped. We were the wealthiest people on the planet, and we had access to the best technology in history. People were willing to do whatever we wanted because we paid well.

We planned a thousand-year trip, a one-way flight to another home. We made arrangements for terraforming ships to arrive a little more than a century before we would, and we took the slow route so that the world would have time to get started before we got there. We knew it would be hard, that after a long sleep we’d wake up to colonize uninhabited territory. We knew there was real risk, but we also knew that the risk on earth was growing with the population. We wanted a new life for ourselves and for our children. We were young, and healthy, and strong.

What we did not count on was the way technology would change. We thought we were leaving a dying world, and we were. As we left the planet the trail of smoke from our burning fuel was our last goodbye, our last contribution to an increasingly unbreathable atmosphere. We meant no harm, but we had to burn some fuel to escape gravity.

Who knew that when we left, the world we left behind would undergo such changes? The population collapse that we expected took place, and we were lucky to escape before it did. That much we foresaw. But we did not think anyone would survive long after we left. When the population decreased, the air and the water started to clean themselves up, at least a little, and the people who made it through that first year of suffering came out of it stronger and more committed to never letting in happen again. They moved more slowly and more carefully than we did. They focused their energies on cleaning up the mess we left behind. And they were pretty good at it, but not good enough. Some of what they did allowed them to survive another few decades, but they saw that the damage was done and the planet was not a place they could stay for long. So they came up with a new plan, to help not just a few people but the whole surviving population of earth to head to the only known survivable exoplanet, one that had been discovered by our investments, and that was already on its way towards being terraformed. They headed for the same planet we had already claimed for our own.

And they arranged to get here first.

I’m writing this while my husband is on the radio, talking with the military patrol that was waiting for us. They say we cannot come down to the surface, and I am trying to hold back my tears. We worked so hard for this, we bought this, we sacrificed everything we had for this, and now they are refusing us entry. They knew we were coming, and they have been waiting for us.

How can they do this to us? We’re the same people, the same species! Humans are nowhere else in the universe. There is no other home for us. The place we all left is uninhabitable, but now they are telling us that we must turn away. I don’t know what this will mean. Do they want us to go back? We cannot; nothing is there waiting for us. Have they found a new place for us to go? My husband has shushed me. The military officer is saying they do not know of other planets. Why are we not allowed here? Why can we not land on the other side of the planet? I know, I’m sorry. I’ll keep it down.

We are traitors, they say. We left them in their time of need, and we left destruction in our wake. They don’t trust us, and they will not let us land. Hasn’t enough time gone by? Can’t we bury the hatchet? Why won’t they forgive us? What are we going to do?

They say they will refuel us. This is their idea of kindness. We are being given enough fuel and supplies to return to Earth. Another millennium of sleep, and perhaps the Earth we left will welcome us home, they say, but we are not welcome here.

My husband is angry. He says that when our ship is refueled he plans to crash it into their city below. They say that they will stop us. They have boarded our ship and sedated my husband. They are about to sedate me, but they are letting me write this last sentence so that when we get back to Earth we will remember their mercy.

Copyright November 10, 2018 David L. O'Hara

A Short Story: Mercy

When we left the Earth we thought we had escaped. We were the wealthiest people on the planet, and we had access to the best technology in history. People were willing to do whatever we wanted because we paid well.

We planned a thousand-year trip, a one-way flight to another home. We made arrangements for terraforming ships to arrive a little more than a century before we would, and we took the slow route so that the world would have time to get started before we got there. We knew it would be hard, that after a long sleep we’d wake up to colonize uninhabited territory. We knew there was real risk, but we also knew that the risk on earth was growing with the population. We wanted a new life for ourselves and for our children. We were young, and healthy, and strong.

What we did not count on was the way technology would change. We thought we were leaving a dying world, and we were. As we left the planet the trail of smoke from our burning fuel was our last goodbye, our last contribution to an increasingly unbreathable atmosphere. We meant no harm, but we had to burn some fuel to escape gravity.

Who knew that when we left, the world we left behind would undergo such changes? The population collapse that we expected took place, and we were lucky to escape before it did. That much we foresaw. But we did not think anyone would survive long after we left. When the population decreased, the air and the water started to clean themselves up, at least a little, and the people who made it through that first year of suffering came out of it stronger and more committed to never letting in happen again. They moved more slowly and more carefully than we did. They focused their energies on cleaning up the mess we left behind. And they were pretty good at it, but not good enough. Some of what they did allowed them to survive another few decades, but they saw that the damage was done and the planet was not a place they could stay for long. So they came up with a new plan, to help not just a few people but the whole surviving population of earth to head to the only known survivable exoplanet, one that had been discovered by our investments, and that was already on its way towards being terraformed. They headed for the same planet we had already claimed for our own.

And they arranged to get here first.

I’m writing this while my husband is on the radio, talking with the military patrol that was waiting for us. They say we cannot come down to the surface, and I am trying to hold back my tears. We worked so hard for this, we bought this, we sacrificed everything we had for this, and now they are refusing us entry. They knew we were coming, and they have been waiting for us.

How can they do this to us? We’re the same people, the same species! Humans are nowhere else in the universe. There is no other home for us. The place we all left is uninhabitable, but now they are telling us that we must turn away. I don’t know what this will mean. Do they want us to go back? We cannot; nothing is there waiting for us. Have they found a new place for us to go? My husband has shushed me. The military officer is saying they do not know of other planets. Why are we not allowed here? Why can we not land on the other side of the planet? I know, I’m sorry. I’ll keep it down.

We are traitors, they say. We left them in their time of need, and we left destruction in our wake. They don’t trust us, and they will not let us land. Hasn’t enough time gone by? Can’t we bury the hatchet? Why won’t they forgive us? What are we going to do?

They say they will refuel us. This is their idea of kindness. We are being given enough fuel and supplies to return to Earth. Another millennium of sleep, and perhaps the Earth we left will welcome us home, they say, but we are not welcome here.

My husband is angry. He says that when our ship is refueled he plans to crash it into their city below. They say that they will stop us. They have boarded our ship and sedated my husband. They are about to sedate me, but they are letting me write this last sentence so that when we get back to Earth we will remember their mercy.

Copyright November 10, 2018 David L. O'Hara

∞

Babel, in Paraphrase

Recently I have been wandering my city with a camera and sketchbook, looking at the ways our use and design of spaces speak about what we value.

Seeing often requires unhasty attention, or training, or both. I can't claim to have training in architecture, but I am trained in semiotics, and I suppose some of my grandfather's years as a toolmaker and my father's career as an engineer have rubbed off on me. Whatever the cause, I care about design.

The ancient story of the Tower of Babel (found in the eleventh chapter of the Book of Genesis) is also a story about design, and semiotics.

It's also a story worth unhasty attention. One hasty version goes roughly like this: everyone on earth shared a common language and common vocabulary. The people, moving to a new place, decided to build a tower to heaven, so they baked bricks and began to build. But they did not finish it; their language became many languages, and they spread out in many directions, divided from one another.

The Bible has a number of stories like this, short tales that seem to be making some simple and clear point. But as we ponder them unhastily - which is what theologians often do - we become more aware of how little we know. The obvious becomes the obscure, and the quotidien becomes mysterious.

A simple story becomes an invitation to slow down even more, and to consider. Selah, it says to us.

At first blush, the story of Babel appears to be a story of human hubris, and of God frustrating that hubris. It could be a simple parallel to the expulsion from Eden, or to the flooding of the earth in the story of Noah: there are limits, and if you transgress those limits, you will make your lot in life worse.

Lately, as I've slowed down my reading, I've been noticing something else: the bricks. The Bible does not often talk about the ethics of technology. There are passages that speak of things like the ethics of weaving, of sharing resources, and of the production, preparation, and distribution of food. But there are not many passages that name a particular human invention in the context of ethics. One of those inventions is named in several places: bricks.

The passage in Genesis 11 talks about bricks as a substitute for stone. When I was young I often worked as a stonemason and bricklayer. That experience may be what draws me to this passage. Bricks are easy to make, and easy to cut. We can standardize them, which makes building walls much faster.

The downside of bricks is related to their upside: they're easy to break, or to cut, or to erode. They don't last as long as stone, and if they're not well-reinforced, they are not as resilient against natural disasters. Some ancient stonemasons figured out how to cut and lay stones that can be jostled by an earthquake and then settle back into position, but bricks often collapse when the ground shakes beneath them. Bricks are easy to use, but they are not as reliable as stone. In comparison to many kinds of stone, bricks are a short-term investment.

This makes me wonder: what was the problem with the Tower of Babel? Was it the fact that the people were trying to build a tower to heaven? Or was it that they were trying to build one badly, or cheaply, or fast? Was it a problem of hubris, or a problem of materials and design? Genesis 11 does not answer that question directly. It leaves it as an open question for us.

Which is just what we should expect, if Genesis 11 conveys any truth. Think about this: how would this story have been told before the Tower of Babel was built? If the story is right, then before the Tower was built, the story would have been told in a language everyone would understand. But now that we have tried to build it (whatever that means) the story must be told in words that are confused, for people who are scattered and divided and who do not share vocabulary.

To paraphrase this: somehow, our use of bricks resulted in making it harder to connect with one another. And it's not clear how.

But somehow, it is a story that hundreds of generations have found worth repeating, even if our words fail to say with precision why that is so.

Maybe, just maybe, it has something to do with the way we continue to build walls of bricks. And what those bricks say about us, and what we value.

Since writing this, I started reading Christopher Alexander's book, The Timeless Way of Building, recommended to me by some friends in Sioux Falls. This line in particular stands out as serendipitous:

Seeing often requires unhasty attention, or training, or both. I can't claim to have training in architecture, but I am trained in semiotics, and I suppose some of my grandfather's years as a toolmaker and my father's career as an engineer have rubbed off on me. Whatever the cause, I care about design.

The ancient story of the Tower of Babel (found in the eleventh chapter of the Book of Genesis) is also a story about design, and semiotics.

It's also a story worth unhasty attention. One hasty version goes roughly like this: everyone on earth shared a common language and common vocabulary. The people, moving to a new place, decided to build a tower to heaven, so they baked bricks and began to build. But they did not finish it; their language became many languages, and they spread out in many directions, divided from one another.

The Bible has a number of stories like this, short tales that seem to be making some simple and clear point. But as we ponder them unhastily - which is what theologians often do - we become more aware of how little we know. The obvious becomes the obscure, and the quotidien becomes mysterious.

A simple story becomes an invitation to slow down even more, and to consider. Selah, it says to us.

At first blush, the story of Babel appears to be a story of human hubris, and of God frustrating that hubris. It could be a simple parallel to the expulsion from Eden, or to the flooding of the earth in the story of Noah: there are limits, and if you transgress those limits, you will make your lot in life worse.

The passage in Genesis 11 talks about bricks as a substitute for stone. When I was young I often worked as a stonemason and bricklayer. That experience may be what draws me to this passage. Bricks are easy to make, and easy to cut. We can standardize them, which makes building walls much faster.

The downside of bricks is related to their upside: they're easy to break, or to cut, or to erode. They don't last as long as stone, and if they're not well-reinforced, they are not as resilient against natural disasters. Some ancient stonemasons figured out how to cut and lay stones that can be jostled by an earthquake and then settle back into position, but bricks often collapse when the ground shakes beneath them. Bricks are easy to use, but they are not as reliable as stone. In comparison to many kinds of stone, bricks are a short-term investment.

*****

This makes me wonder: what was the problem with the Tower of Babel? Was it the fact that the people were trying to build a tower to heaven? Or was it that they were trying to build one badly, or cheaply, or fast? Was it a problem of hubris, or a problem of materials and design? Genesis 11 does not answer that question directly. It leaves it as an open question for us.

Which is just what we should expect, if Genesis 11 conveys any truth. Think about this: how would this story have been told before the Tower of Babel was built? If the story is right, then before the Tower was built, the story would have been told in a language everyone would understand. But now that we have tried to build it (whatever that means) the story must be told in words that are confused, for people who are scattered and divided and who do not share vocabulary.

To paraphrase this: somehow, our use of bricks resulted in making it harder to connect with one another. And it's not clear how.

But somehow, it is a story that hundreds of generations have found worth repeating, even if our words fail to say with precision why that is so.

Maybe, just maybe, it has something to do with the way we continue to build walls of bricks. And what those bricks say about us, and what we value.

*****

Update:Since writing this, I started reading Christopher Alexander's book, The Timeless Way of Building, recommended to me by some friends in Sioux Falls. This line in particular stands out as serendipitous:

"But in our time the languages have broken down. Since they are no longer shared, the processes which keep them deep have broken down: and it is therefore virtually impossible for anybody, in our time, to make a building live." (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979) p. 225

∞

Wendell Berry: Past A Certain Scale, There Is No Dissent From Technological Choice

“But past a certain scale, as C.S. Lewis wrote, the person who makes a technological choice does not choose for himself alone, but for others; past a certain scale he chooses for all others. If the effects are lasting enough, he chooses for the future. He makes, then, a choice that can neither be chosen against nor unchosen. Past a certain scale, there is no dissent from technological choice.”

-- Wendell Berry, “A Promise Made In Love, Awe, And Fear,” in Moral Ground: Ethical Action For A Planet In Peril. Kathleen Dean Moore and Michael P. Nelson, eds. (San Antonio: Trinity University Press, 2010) p. 388.

∞

Trained By Trains - Thoreau on Technology

I'm teaching Thoreau's Walden this semester, and tomorrow my class will discuss the chapter entitled "Sounds." While re-reading it tonight I was struck by two passages about trains and the way this new technology was changing the people who lived near it.

Here's the first passage:

It may sound like Thoreau admires this change, but he does not. Just a little earlier he wrote that when he was at Walden his "days were not days of the week, bearing the stamp of any heathen deity, nor were they minced into hours and fretted by the ticking of a clock." His Walden-time is not "minced into hours." That is, it is not governed by any clock but Thoreau himself.

The other passage is one where he imagines the trains as "bolts" or arrows:

A hundred and seventy years ago Thoreau was already seeing the ways that a single technology - one heralded as beneficent and neutral - was remaking us in its image, changing our sense of time, speeding us up, educating us to stay out of its way and so confining us to the spaces between the spaces it occupies.

And it's not just those who ride the railroad who are conditioned by it; everyone is conditioned by it. The technology is not neutral, not a mere thing we can wield with no effect upon the wielder. We may devise tools, but we are ignorant if we think that the tools do not also come to change us.

Here's the first passage:

"Far through unfrequented woods on the confines of towns, where once only the hunter penetrated by day, in the darkest night dart these bright saloons without the knowledge of their inhabitants….They go and come with such regularity and precision, and their whistle can be heard so far, that the farmers set their clocks by them, and thus one well-conducted institution regulates a whole country. Have not men improved somewhat in punctuality since the railroad was invented? Do they not talk and think faster in the depot than they did in the stage-office? There is something electrifying in the former place."The Fitchburg Railroad had been very recently built in his time. Despite the short time it had been in existence, already it had begun to change the way people who lived near it regarded time.

It may sound like Thoreau admires this change, but he does not. Just a little earlier he wrote that when he was at Walden his "days were not days of the week, bearing the stamp of any heathen deity, nor were they minced into hours and fretted by the ticking of a clock." His Walden-time is not "minced into hours." That is, it is not governed by any clock but Thoreau himself.

The other passage is one where he imagines the trains as "bolts" or arrows:

"We live the steadier for it. We are all educated thus to be sons of Tell. The air is full of invisible bolts."To be a son of William Tell is no pleasant thing. To be a son of Tell is to be constantly in mortal peril. One's schoolmaster is the permanent risk of sudden death.

A hundred and seventy years ago Thoreau was already seeing the ways that a single technology - one heralded as beneficent and neutral - was remaking us in its image, changing our sense of time, speeding us up, educating us to stay out of its way and so confining us to the spaces between the spaces it occupies.

And it's not just those who ride the railroad who are conditioned by it; everyone is conditioned by it. The technology is not neutral, not a mere thing we can wield with no effect upon the wielder. We may devise tools, but we are ignorant if we think that the tools do not also come to change us.

∞

As September approaches, people keep asking me, "Are you ready to get back in the classroom?"

As early as middle school I knew I wanted to become a college professor, and I love my job. It is a delight to spend time with young people who are curious, after all.

Years ago, my friend Matt Dickerson pointed out to me that it's also my job to help those who are not curious to see why they should be. As it turns out, that work is usually delightful, too, a rewarding challenge.

So on the whole, I love my work.

But I admit I don't love classrooms, for several reasons:

First, no matter what decade, every classroom I've been in has exhibited an unhealthy tendency towards becoming cluttered with the latest technology, and most of that tech seems to take up a lot of space and to become the center of attention. I'm not opposed to technology in the classroom, not at all. But I'm opposed to letting it get in the way, as it does when the "Smart Cart" leaves me no room for my lecture notes, or when I can't seem to turn the ceiling-mounted projector on or off. I'm a fan of chalk, because chalk allows spontaneity, and it allows for much more than alphanumeric writing in neat rows. Sadly, concerns about chalk dust getting into computers is threatening to make chalkboards disappear from my classrooms. Alas. Chalk is an excellent technology, and if it vanishes, I will mourn its loss.

Second, classroom architecture is not some value-free, neutral design. Classroom architecture makes a big difference in how people teach, and how they learn:

Which is why, as often as I can, I get my students out of the classroom. When we are reading Thoreau's Walking, we go for a walk. When I teach environmental philosophy, we often meet under the great tree in our campus quad, where I encourage students to daydream and to play with the grass, to look for worm-castings and owl pellets, feathers and seed-pods, invertebrates and fallen bits of bark. What good is it to gain the world of theoretical knowledge at the expense of knowledge gained through vital, haptic, bodily experience?

And this is why I am a preacher of the importance of study abroad. Not just travel, but serious, engaged, rigorous study in the classroom of life in another place. This is why I teach Classics in Greece every year, and why year after year I take students to Central America to study environmental philosophy and ecology.

More and more I've been trying to shift the learning focus in my classes from the classroom to the laboratory - where by "laboratory" I mean anywhere that allows students to learn with their whole person. I make my ancient philosophy students devote hours each semester to star-gazing, in part because this is what the ancients did, and in part because I don't want them to miss the stars. I want them to gaze in wonder at the firmament so that when they read Aristotle and Galileo they know that they've looked at what those great minds saw as well. We even occasionally take field trips to really dark places like the South Dakota Badlands so we can see the skies even better.

My environmental philosophy students must observe a square meter of earth for a semester, spending an hour at a time without a camera, drawing and writing about what they see, because it does not make sense to me to talk about the earth when you have not taken the time to sit upon it, to listen to it, to smell and taste it, and to see what other lives creep, and walk, and fly across it.

My friend Aage Jensen advocates the Norwegian philosophy of Friluftsliv, life and education outdoors. And when he organizes a conference on it, he eschews conference centers and holds the conference while walking through the mountains, or paddling a river. Because he believes that one should practice what one preaches, and that nature is always ready to teach.

To paraphrase the Stoic Musonius, teachers would do well to talk less and to take their students with them into the fields, because there they will learn far better and far more than in the lecture hall.

Teaching Outdoors

|

As early as middle school I knew I wanted to become a college professor, and I love my job. It is a delight to spend time with young people who are curious, after all.

Years ago, my friend Matt Dickerson pointed out to me that it's also my job to help those who are not curious to see why they should be. As it turns out, that work is usually delightful, too, a rewarding challenge.

So on the whole, I love my work.

But I admit I don't love classrooms, for several reasons:

First, no matter what decade, every classroom I've been in has exhibited an unhealthy tendency towards becoming cluttered with the latest technology, and most of that tech seems to take up a lot of space and to become the center of attention. I'm not opposed to technology in the classroom, not at all. But I'm opposed to letting it get in the way, as it does when the "Smart Cart" leaves me no room for my lecture notes, or when I can't seem to turn the ceiling-mounted projector on or off. I'm a fan of chalk, because chalk allows spontaneity, and it allows for much more than alphanumeric writing in neat rows. Sadly, concerns about chalk dust getting into computers is threatening to make chalkboards disappear from my classrooms. Alas. Chalk is an excellent technology, and if it vanishes, I will mourn its loss.

Second, classroom architecture is not some value-free, neutral design. Classroom architecture makes a big difference in how people teach, and how they learn:

|

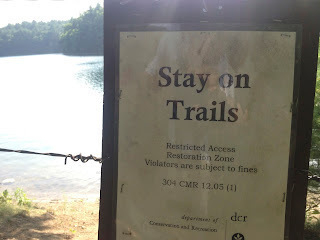

| Step off the trails! Explore! An ironic sign at Walden Pond. |

And this is why I am a preacher of the importance of study abroad. Not just travel, but serious, engaged, rigorous study in the classroom of life in another place. This is why I teach Classics in Greece every year, and why year after year I take students to Central America to study environmental philosophy and ecology.

More and more I've been trying to shift the learning focus in my classes from the classroom to the laboratory - where by "laboratory" I mean anywhere that allows students to learn with their whole person. I make my ancient philosophy students devote hours each semester to star-gazing, in part because this is what the ancients did, and in part because I don't want them to miss the stars. I want them to gaze in wonder at the firmament so that when they read Aristotle and Galileo they know that they've looked at what those great minds saw as well. We even occasionally take field trips to really dark places like the South Dakota Badlands so we can see the skies even better.

My environmental philosophy students must observe a square meter of earth for a semester, spending an hour at a time without a camera, drawing and writing about what they see, because it does not make sense to me to talk about the earth when you have not taken the time to sit upon it, to listen to it, to smell and taste it, and to see what other lives creep, and walk, and fly across it.

My friend Aage Jensen advocates the Norwegian philosophy of Friluftsliv, life and education outdoors. And when he organizes a conference on it, he eschews conference centers and holds the conference while walking through the mountains, or paddling a river. Because he believes that one should practice what one preaches, and that nature is always ready to teach.

To paraphrase the Stoic Musonius, teachers would do well to talk less and to take their students with them into the fields, because there they will learn far better and far more than in the lecture hall.

|

| Nature is full of things worth seeing. |

∞

This year I am playing around with Google Wave's map feature and wondering if I can use Wave to help prepare my students to make the most of our limited time in Greece.

Do you have suggestions for how I can use this for my course? Are you also new to Wave and interested in Greece? If so, send me a wave at dr.dlohara@googlewave.com and I'll include you in my "sandbox" where I'm playing around with the possibilities.

(Photo credit: Dr. Jeffrey A. Johnson, Providence College)

Google Wave and My Course in Greece

Each year I teach a course in Greece, and I require my students to make presentations at a variety of archaeological and cultural sites.

This year I am playing around with Google Wave's map feature and wondering if I can use Wave to help prepare my students to make the most of our limited time in Greece.

Do you have suggestions for how I can use this for my course? Are you also new to Wave and interested in Greece? If so, send me a wave at dr.dlohara@googlewave.com and I'll include you in my "sandbox" where I'm playing around with the possibilities.

(Photo credit: Dr. Jeffrey A. Johnson, Providence College)