theology

Reason For Hope

Apologetics and Postmodernism

When I first taught it, I made it a class about apologetics and postmodernism. By “apologetics” I mean the work of giving a reasoned account of one’s commitments; by “postmodernism,” I mean the suspicion that what look like reasoned accounts might have unexamined depths and layers to them. In the context of theism—and in particular Christian theism—apologetics has a long history that reaches back to the early years of Christianity. Saint Peter wrote in his longer letter that Christians should always be prepared to give a reasoned defense of the hope they bore within them. That phrase “reasoned defense” is a translation of the Greek word apologia, which can mean a legal defense, and from which we get our word “apologetics.”

When Saint Paul of Tarsus found himself in Athens, speaking to Stoic and Epicurean philosophers on the Areopagus, he tried to explain his beliefs not in the terms of his culture but in theirs. He doesn’t seem to have won many over to his views that day, but if nothing else was accomplished, at the end of the conversation it was clearer where Paul and the Greek philosophers were in agreement and where they disagreed. If immediate conversion was the aim of his speech, it wasn’t a great speech. But if he aimed to build a bridge of mutual understanding, I’d say he was pretty successful.

One of the keys to his success, I think, was familiarity with the culture around him. I’ve written about this elsewhere, so I won’t belabor it here, but I’ll just point out that Paul quoted two Greek philosophical poets, Epimenides and Aratos, and he did so in a culturally appropriate and significant place, since several centuries before Paul’s travels, Epimenides (who was from Crete) also traveled to Athens and also spoke on the Areopagus about the gods and salvation.

Understanding Atheism(s)

A few years after I started teaching that course, I shifted the course to take seriously the “New Atheists.” I figured that if my religious students graduated without hearing the strongest challenges to their faith, I, as a professor who teaches theology, was letting them down. I wanted them to know that soon they’d hear strong arguments against their religious heritage, beliefs, and practices, and that these arguments should be taken seriously. For my Christian students, I framed this as a way of living the commandment to love God with one’s mind.

Of course, only some of my students are religious, and some of the religious students aren’t Christians. (I’m at a Lutheran university in a small Midwestern city, so until recently most of them were at least culturally Christian; that’s changing quickly, though.) I wanted this to be a class that was helpful for everyone, so I started to turn this into a class about mutual understanding. I now teach my students how to distinguish between a dozen different kinds of (and reasons for) atheism, lest they make the mistake of oversimplifying the complexity of their neighbors and of themselves.

Understanding and Agapic Love

Arguments about religion can quickly become unkind. Many of us have been wounded in the name of religion, and those wounds heal slowly, if at all. How could we make this into a class that was—on its surface, and in its content—about theology and philosophy, while really making it about something like mutual care?

I just mentioned that great commandment: Love God with your heart, soul, mind, and strength, Jesus said, echoing Moses. Then he added a second commandment: love your neighbor as yourself. Everything else hangs on these two commandments, he said.

Explaining those two commandments would be almost as hard as trying to keep them, so I won’t try to do so here. I’ll just point out that it’s fascinating to command someone to love someone else; that the love that’s called for here is agapic love, i.e. the love that seeks the good and flourishing of the beloved; and that the commandments are so lacking in specificity as to call for both extensive commentary and continued practice. They’re vague commandments, which means they require us to work them out in community, over time. And in all likelihood we’ll never get them right. That may seem like a weakness, but it also strikes me as offering the freedom to try and to fail and to help one another to try again.

Anxiety, Ultimate Concerns, and Societal “Stress Fractures”

Which brings me to the most recent incarnation of my Theology and Philosophy in Dialogue class. Over the last few years it seems to me that my students have become more anxious about their economic futures, more stressed about exams and jobs, more focused on education and work as competition for rank. I could be wrong, but as the stress and anxiety have grown, it seems like my students are so busy jockeying for position that they have a hard time putting the cause of their stress into words. On top of all this, here in the United States, it feels like we’ve been using stronger words so that we can give voice to our anxiety more quickly. We aren’t broken, but we’ve got lots of hairline stress fractures that are too small to see. We aren’t bleeding, but we’ve got a constant dull ache.

In other words, it seems like we’re fearful without being able to identify the object of our fear, and that has us prepared to see enemies wherever we look. This does not make it easy to love our neighbors as ourselves (unless we also have that kind of distrust of ourselves, which is a real possibility, I suppose.) And at least in the way Paul Tillich described God: whatever we regard as our ultimate concern functions as our God. When economic anxiety, jostling for rank, or fear of losing one’s place in the future, (these are all ways of saying the same thing, I think) take on the role of “ultimate concern” in our lives, they become our gods.

The course I’m teaching this semester still has traces of every previous semester’s influences. We talk a little about apologetics, and that’s a helpful way of teaching students about logic, inference, probability, and certainty. (Ask some of them about “doxastic certainty” or my “haystack problem” and you’ll see what I mean.)

And we still talk about postmodernism, though as my career has shifted from the philosophy of religion to environmental philosophy, ethics, and policy, I’m inclined to follow Scott Russell Sanders’ view (see note, below) that if we spend too much time theorizing and not enough time caring for the world we share, incredulity towards metanarratives can quickly become a new metanarrative that we fail to examine sufficiently.

And we still talk about atheisms. This semester I have sketched a dozen forms of atheism once again, and we’re now working our way through them.

Friendship, and “Best Construction”

But the aim of the class, more than anything, is friendship.

I told all the students that this was the case on the first day of class.

And here, I think, is where Theology and Philosophy can have a really helpful dialogue in our time. I teach at a Lutheran university, so it’s fitting to invoke Luther. In his Small Catechism, he offers some commentary on the Ten Commandments. His commentary on the eighth commandment is helpful. The commandment reads simply, like this:

“Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor.”Like the other commandments I’ve mentioned, it is only a few words long. And like those others, it leaves room for commentary. Luther’s commentary does something that I find very helpful. While the commandment is negative (“thou shalt not,” it says) Luther thought that alongside each negative commandment was something positive. So he writes:

What does this mean?--Answer. We should fear and love God that we may not deceitfully belie, betray, slander, or defame our neighbor, but defend him, [think and] speak well of him, and put the best construction on everything.”This is akin to what Plato offers in several ways in his Republic, and to Ulpian’s legal principle of “giving to each person their due,” (see note, below) but it goes a little further, with an agapic tinge: Luther doesn’t just tell us not to lie, nor does he tell us to be simply honest, but to put the best construction on everything.

This is hard.

“A Mutual, Joint-Stock World, In All Meridians”

It’s especially hard when we feel that others are getting ahead of us, and that we are in a competition with everyone else. If the world is a zero-sum game, then everyone run, and the Devil take the hindmost. But what if Queequeg is right? When Queequeg sees a fellow sailor drowning and no one moves to save the sailor, Queequeg leaps into the water to save his fellow. There is no question of whether they are of the same tribe, the same party, the same race, the same team. Queequeg is, as far as anyone aboard the ship knows, a cannibal. And yet the narrator, observing Queequeg’s agapic care for his fellow sailor, offers this comment:

Was there ever such unconsciousness? He did not seem to think that he at all deserved a medal from the Humane and Magnanimous Societies. He only asked for water—fresh water—something to wipe the brine off; that done, he put on dry clothes, lighted his pipe, and leaning against the bulwarks, and mildly eyeing those around him, seemed to be saying to himself—“It’s a mutual, joint-stock world, in all meridians. We cannibals must help these Christians.” -- Herman Melville, Moby Dick. (New York: Signet, 1980) 76

It’s much easier to approach theological conversations with the idea that our theology is a weapon and that our enemies are those with whom we disagree. It’s so easy to forget what Saint Paul wrote, that we don’t fight against flesh and blood, but against far less tangible, invisible forces that would have us view our neighbors with malice.

Could we approach theology the way Queequeg approaches the plight of his fellow sailor? Is it possible to maintain one’s cherished beliefs while recognizing that one’s object of “ultimate concern” might be something we don’t yet see with certainty and clarity? I cannot speak for others, so I’ll just offer this confession: I’m aware of a capacity in myself to care more for my theology than for the God that my theology claims to describe. In simpler terms: my own theology can become so dear to me that it becomes an idol, displacing the very God I set out to love and serve. And how to I love and serve my God? So far, the best I can offer you is this: I should love God with all I am, and I should love my neighbor as myself. Does that seem unclear to you? It does to me. Which means I need all the help I can get in clarifying my vision. Right now I see in a glass, darkly.

The philosopher Jonathan Lear suggests a principle akin to Queequeg’s, and to Luther’s: the principle of humanity. He describes it like this:

“The interpretation thus fits what philosophers call the principle of humanity: that we should try to interpret others as saying something true—guided by our own sense of what is true and of what they could reasonably believe.” -- Jonathan Lear, Radical Hope. 4 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006) (See note below)The Episcopal Church’s Book of Common Prayer offers another commentary on the fourth commandment, the commandment not to take the name of God in vain. The Book of Common Prayer rephrases the commandment like this:

You shall not invoke with malice the Name of the Lord your God.

Amen. Lord have mercy.The rephrasing is a commentary on “in vain.” Invoking God’s name in vain is equated with invoking it with malice, that is, with the opposite of agapic love.

Conclusion

It’s appropriate to me that I teach this course in Lent each year. Lent is a good time for self-examination, and that includes an examination of all kinds of pieties and supposed certainties. What is it that we hold to be of ultimate concern? What do we love with all our heart, soul, mind, and strength? That might just be playing the role of a god in our lives. If so, does that God help us to love our neighbors as ourselves?

I could be wrong in all I say in this class. I enter it with “fear and trembling,” knowing that there’s so much I don’t know, and knowing that many of my students might be wiser than I am. I know they might have seen the divine far more clearly than I ever will in this life.

But oh, how I want them to live well, not to be entangled by anxious grief, not to be afraid of the future, not to be burdened by relentless suspicions and fears.

Yes, there are other subjects I could teach, and yes, there are other jobs I could do. But for me, right now, this one feels like a good way to reexamine my own ultimate concerns, and a good way to help others to do the same. May I do so without malice, with agapic love, and with the constant practice of putting the best construction on everything.

Amen. Lord, have mercy.

*****

Notes:

* Scott Russell Sanders: I'm thinking of his essay, "The Warehouse and the Wilderness," and in particular the opening pages of that essay. You can find it in A Conservationist Manifesto, beginning on page 71. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009)

* Ulpian's words are cited in Justinian, Institutes, Book 1, Title 1, Sec. 3.

* Lear has an endnote at the end of this sentence. It reads: “This principle is also known as the ‘principle of charity,’ and the most famous arguments for it are given by Donald Davidson. See his “Radical Interpretation,” in Inquiries Into Truth And Interpretation (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984), pp. 136-137; “Belief and the Basis of Meaning,” ibid., pp. 152-153; “Thought and Talk,” ibid., pp. 168-169; “On the Very Idea of a Conceptual Scheme,” ibid., pp. 196-197; “The Method of Truth in Metaphysics,” ibid., pp. 200-201.”

Pragmatic Stoic Theology

Chrysippus' god-argument is not, strictly speaking, a proof of the existence of a god. It is rather an appeal to what he thinks is common sense, and to the consequences of not believing.

The first part, the appeal to common sense, goes something like this:

1) If there is anything in nature that we can't have made then something greater than us made it;

2) That something is what we call a god.Of course, he is assuming that everything that exists must exist because it was made, and that it was made designedly by a single cause. We could object that natural arrangements might have more than one lesser natural cause; or we could contest the whole notion of greater and lesser and dismiss this part of his argument fairly easily.

The second part makes a case that at least invites us to be cautious about dismissing it too readily. It goes like this:

3) Unless there is divine power, human reason is the greatest thing we know of and can possess;

4) So if there are no gods, then we are the greatest beings in the cosmos. In which case, we are the gods.Of course there might be other things we don't know of that are more powerful than we are; or we might (wisely) regard nature as more powerful than we are.

But the most helpful part, I think, is (4), which stands as an invitation to consider who we are as we face the cosmos. We think of ourselves as natural, but we also think of ourselves as standing somehow apart from nature.

So it may be that there is nothing in the cosmos wiser or more clever than we are. We should be honest about this and acknowledge the real possibility that this is the case.

But Chrysippus invites us also to consider the consequences of that belief, since it could be taken as license to act as we will. The danger, as he sees it, is that we might become the sort of people who worship ourselves. This is dangerous in part because it impedes growth; we become like what we worship, and if we worship only ourselves, then we become our own best ideal. I will speak for myself when I say that I, at least, am a cramped and stingy ideal.

Many of the Stoics are content to name nature as god; what matters is that there always be something worth our attention and admiration. I'm reminded of the wise words of David Foster Wallace, who said that

There is no such thing as not worshipping. Everybody worships. The only choice we get is what to worship. And an outstanding reason for choosing some sort of god or spiritual-type thing to worship - be it JC or Allah, be it Yahweh or the Wiccan mother-goddess or the Four Noble Truths or some infrangible set of ethical principles - is that pretty much anything else you worship will eat you alive.You can read the rest of his brief, insightful talk here (or by searching for "This Is Water.")

Wallace comes pretty close to Chrysippus. Neither is trying to convert you to a religion, neither is trying to set the rules for your life, but both are reporting on what they have seen when they have ventured in the direction of denying all the gods: off in that direction, they found they could escape all the gods except the god they then found that they forced themselves to become.

Which, to paraphrase Wallace, is a good reason for choosing to posit some god which, if it existed, would be worth your worship. And then, maybe, to test it by trying to worship it as though it were really there.

Animal Sacrifice And Factory Farming

“In the period of the history of the Christian Church, we have traveled from a time in which the killing of animals was only permitted within religious rituals to a time in which 60 billion animals per year are killed for human consumption, the majority of which are raised, slaughtered and processed in factory conditions far removed from the sight or concern of their consumers.”

David L. Clough, On Animals: Volume I, Systematic Theology (London: T&T Clark, 2012) (xiii)

Proofs of God's Existence

Too often I have seen Anselm's "ontological" argument abstracted from its context, as though the fact that his Proslogion begins with a prayer were inconsequential to the argument; or Descartes' proofs abstracted from his Meditations, as though it were not important that "God" serves an instrumental purpose for Descartes, allowing for the re-establishment of the world after he doubts its existence.

Anselm already believes when he writes his argument. He has arrived at his belief in some way other than argumentation, and there is no shame in that. Most of us arrive at most of our beliefs in less-than-purely-rational ways, and as William James has argued, we have the right to do so. It looks to me like Anselm is writing not in order to defeat all atheism (though that may be one of his aims) but in order to see if his faith and his understanding can be in agreement with one another.

Descartes might believe or he might not; I don't know how I could know. God matters in his Meditations because God offers an "Archimedean point," a fulcrum on which to rest the lever of reason, allowing Descartes to lift the world anew from the ruins of doubt. Whether or not Descartes believes in God's existence, God is useful to Descartes.

My point is that it is mistaken to assume that arguments about God - for or against God - are detached and detachable from other concerns, and when we neglect those concerns we might just be missing the most important aspect of those arguments, namely the human aspect. When we argue about God, we are usually also arguing about something else.

Happy Praise

"Thou art worthy at all times to be praised by happy voices, O Son of God, O Giver of Life..."It needn't be translated that way, by the way. It could be translated as "reverent voices" or "opportune voices." I like this translation, though. The sentiment is positively Epicurean. Consider the opening line of Epicurus's Kuriai Doxai*:

"What is blessed and indestructible has no troubles itself, nor does it give trouble to anyone else..."**In Epicurus's view, a god that is petulant or demanding is a god that is needy and manipulative. Such gods may force us to make sacrifices, but they won't earn our praise so much as our derision and scorn. A god worthy of the name is one that needs and demands nothing for itself.

I'm preparing a scholarly article on St Paul's response to Epicurean philosophy, one I hope to publish soon. For now, I will summarize one of its points: Christians and Epicureans disagree about the imperturbability of the divine (Christians disagree among themselves about this as well) but they agree that if something can't be praised with gladness at least sometimes, then it's probably not worth praising at all.

This is not just abstract philosophy or theology; it matters for all of life. We are all always engaged in worship, as David Foster Wallace once said. We don't get much choice about that. We do have a choice about what we worship - what we ascribe worth to. We do that all the time when we vote, when we spend and invest our money, when we decide what our laws should be and what our children should learn. We constantly make decisions about ends that should be pursued, and these are all acts of worship.

** Diogenes Laertius, 10.139; from The Epicurus Reader, Brad Inwood and Lloyd Gerson, translators. (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1994) p. 32.

All Your Deeds

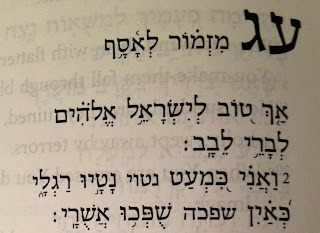

The last line caused me some trouble, though. In it Asaph, the psalmist, says "I will tell of all your [God's] deeds."

Okay, what exactly are those deeds? What can we ever reliably say about God's deeds? If God had done something in history that were not open to historical doubt, there would be no atheists.

The tradition gives us stories about God, and a century of biblical criticism calls those stories myths. Still, as I have argued elsewhere (here, and here, for example) myth is not - or should not be taken as - a synonym for falsehood. Stories may be myths and true, even if not historically true.

As Howard Wettstein argues in his Significance of Religious Experience,

The Bible’s characteristic mode of ‘theology’ is story telling, the stories overlaid with poetic language. Never does one find the sort of conceptually refined doctrinal propositions characteristic of a doctrinal approach. When the divine protagonist comes into view, we are not told much about his properties. Think about the divine perfections, the highly abstract omni-properties (omnipotence, omniscience, and the like), so dominant in medieval and post-medieval theology. One has to work very hard—too hard—to find even hints of these in the Biblical text. Instead of properties, perfection and the like the Bible speaks of God’s roles—father, king, friend, lover, judge, creator, and the like. Roles, as opposed to properties; this should give one pause. (108, emphasis added)The stories may not be about historical "deeds" but may be about the character, the roles of God.

Which makes me wonder: what roles does God play in my life? What "deeds" may I speak of?

|

| The preface to the complaint in Psalm 73 |

Before I reply, let me hasten to say this: I am often reluctant to write too strongly about this sort of thing because I do not want to say that others must believe what I believe. If God has led me to belief, (grant me that for the sake of argument for a moment) God has not strong-armed me into belief but allowed me to arrive at my beliefs over time, letting them be shaped by experience. I do not see why I should allow you less liberty than God has allowed me.

So I write the following admitting that I do not know what I am writing about. As Augustine confessed, when I speak of my love for God, I do so simultaneously wondering what I mean by "God." What can I compare God to? What is God like? I do not know how to answer those questions, except by telling stories, expositing roles. So here goes:

When I was a child, belief in God motivated a family in my neighborhood to care about me and to welcome me into their home when my family was falling apart. Without that love...I shudder to think what I would be today.

God gives me a name for what I pray to. God gives me a focal point for my attention in the vast cosmos, and God gives me a sense that in such a cosmos persons matter. And because persons matter, justice matters. This is not to say one cannot be just without belief, or that belief makes one just - far from it! - only that I find for myself the two ideas closely bound together.

God gives me solace in my mourning and hope when I pray. My mother is dead, but when I speak to God about her, she is not lost.

God gives me a story about the centrality of nurturing love. A reason to think all things are related. Someone to thank. Someone to be angry with. Rest for my soul. Quietness, and in it, trust.

God gives me a story about giving, and why giving and receiving should matter so much.

A story about why, and how, to turn a guilty conscience into repentance. A reason to forgive, and, very often, the strength to forgive. And to hope that I too am forgivable.

A reason to hope that no one is beyond redemption, beyond all hope, completely unworthy of love.

Belief that every person matters. More than that, belief that a teenage girl could be a vessel of the divine; that a third-world martyred prophet could save the world; that an inarticulate foreigner could be a world-historical lawgiver; that a persecuting zealot could get hit so hard by grace that he lives the rest of his life to preach good news for all people everywhere.

Hope that prison doors could be opened, that tongues could be loosed, that great art and great music might be signs of the divine.

I could be wrong about all of this, I know. I know there are other explanations of what I have written above. I also know those explanations apply to music, too, and I'm not interested in hearing about them there either if the reason for offering them is to help disabuse me of my love for good music. I know that people use the same word I use here to justify violence, self-interest, and hatred. I cannot help but feel angry and disgusted when it is used for those ends, ends which seem so contrary to what the word means for me, ends that make me think someone has read the wrong script, mis-cast the character, not known what deeds God has done.

Wettstein on Narrative Theology

“We often speak of the biblical narrative, and narrative is another aspect of the Bible’s literary character. The Bible’s characteristic mode of ‘theology’ is story telling, the stories overlaid with poetic language. Never does one find the sort of conceptually refined doctrinal propositions characteristic of a doctrinal approach. When the divine protagonist comes into view, we are not told much about his properties. Think about the divine perfections, the highly abstract omni-properties (omnipotence, omniscience, and the like), so dominant in medieval and post-medieval theology. One has to work very hard—too hard—to find even hints of these in the Biblical text. Instead of properties, perfection and the like the Bible speaks of God’s roles—father, king, friend, lover, judge, creator, and the like. Roles, as opposed to properties; this should give one pause.” (108)

I will confess that this is a difficult review to write; it's rare that I find a book that I'd rather quote at great length rather than summarize. His writing is lucid, combining analytic rigor and pragmatic vision with Talmudic wisdom. It is delicious in its suggestiveness. It's the sort of book I expect will tinge everything I write for a long time.“Biblical theology is poetically infused, not propositionally articulated.” (110)

Theology and Theomythy

I was just reading Jamie Smith’s recent post on “Poetry and the End of Theology” over at his Fors Clavigera blog. His post reminded me of something I was thinking of several years ago when I was writing From Homer to Harry Potter.

Back in Homer’s time, the words λογος (logos) and μυθος (mythos) were near synonyms. Over time, they came to be distinguished from one another as meaning something like “an account in propositions” (logos) and “an account in stories” (mythos).

The word “logos” is one of the roots of our word “theology,” of course. Theology, then, means something like the attempt to discuss the divine in a logical and propositional manner. Which is all well and good, unless it begins to turn God into something we only analyze and never experience, about which we speak propositions but whose story never means much to us.

As a philosopher of religion, I think theology is important. The things we believe have consequences for us and for others. As one of my mentors, Ken Ketner, puts it, “Bad thinking kills people.” We know this from experience: people use theological ideas to justify all sorts of unethical behavior.

Nevertheless, theology is pretty dry stuff, and its very dryness has a genealogy and has consequences that we should be aware of. As Jamie puts it, some of the dryness of contemporary theology comes from a Cartesian anthropology that assumes that the most important part of us is that we are thinking things - things that care chiefly about propositions. If all we care about is getting our religion right, than this is the kind of theology we need, I suppose.

But is that what we are? Are we not also beings who live in the world, who live out stories, and who tell stories? Aren’t creativity and poetry and loveliness important to us as well? This got me thinking: maybe what we need is less theology and more theomythy. I’m not sure just what that would look like, but I think it might be worth a try. I’m interested in what you believe, sure. But I’m also interested in hearing your story.