theomythy

All Your Deeds

The last line caused me some trouble, though. In it Asaph, the psalmist, says "I will tell of all your [God's] deeds."

Okay, what exactly are those deeds? What can we ever reliably say about God's deeds? If God had done something in history that were not open to historical doubt, there would be no atheists.

The tradition gives us stories about God, and a century of biblical criticism calls those stories myths. Still, as I have argued elsewhere (here, and here, for example) myth is not - or should not be taken as - a synonym for falsehood. Stories may be myths and true, even if not historically true.

As Howard Wettstein argues in his Significance of Religious Experience,

The Bible’s characteristic mode of ‘theology’ is story telling, the stories overlaid with poetic language. Never does one find the sort of conceptually refined doctrinal propositions characteristic of a doctrinal approach. When the divine protagonist comes into view, we are not told much about his properties. Think about the divine perfections, the highly abstract omni-properties (omnipotence, omniscience, and the like), so dominant in medieval and post-medieval theology. One has to work very hard—too hard—to find even hints of these in the Biblical text. Instead of properties, perfection and the like the Bible speaks of God’s roles—father, king, friend, lover, judge, creator, and the like. Roles, as opposed to properties; this should give one pause. (108, emphasis added)The stories may not be about historical "deeds" but may be about the character, the roles of God.

Which makes me wonder: what roles does God play in my life? What "deeds" may I speak of?

|

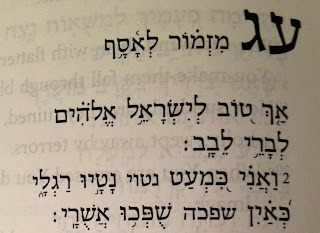

| The preface to the complaint in Psalm 73 |

Before I reply, let me hasten to say this: I am often reluctant to write too strongly about this sort of thing because I do not want to say that others must believe what I believe. If God has led me to belief, (grant me that for the sake of argument for a moment) God has not strong-armed me into belief but allowed me to arrive at my beliefs over time, letting them be shaped by experience. I do not see why I should allow you less liberty than God has allowed me.

So I write the following admitting that I do not know what I am writing about. As Augustine confessed, when I speak of my love for God, I do so simultaneously wondering what I mean by "God." What can I compare God to? What is God like? I do not know how to answer those questions, except by telling stories, expositing roles. So here goes:

When I was a child, belief in God motivated a family in my neighborhood to care about me and to welcome me into their home when my family was falling apart. Without that love...I shudder to think what I would be today.

God gives me a name for what I pray to. God gives me a focal point for my attention in the vast cosmos, and God gives me a sense that in such a cosmos persons matter. And because persons matter, justice matters. This is not to say one cannot be just without belief, or that belief makes one just - far from it! - only that I find for myself the two ideas closely bound together.

God gives me solace in my mourning and hope when I pray. My mother is dead, but when I speak to God about her, she is not lost.

God gives me a story about the centrality of nurturing love. A reason to think all things are related. Someone to thank. Someone to be angry with. Rest for my soul. Quietness, and in it, trust.

God gives me a story about giving, and why giving and receiving should matter so much.

A story about why, and how, to turn a guilty conscience into repentance. A reason to forgive, and, very often, the strength to forgive. And to hope that I too am forgivable.

A reason to hope that no one is beyond redemption, beyond all hope, completely unworthy of love.

Belief that every person matters. More than that, belief that a teenage girl could be a vessel of the divine; that a third-world martyred prophet could save the world; that an inarticulate foreigner could be a world-historical lawgiver; that a persecuting zealot could get hit so hard by grace that he lives the rest of his life to preach good news for all people everywhere.

Hope that prison doors could be opened, that tongues could be loosed, that great art and great music might be signs of the divine.

I could be wrong about all of this, I know. I know there are other explanations of what I have written above. I also know those explanations apply to music, too, and I'm not interested in hearing about them there either if the reason for offering them is to help disabuse me of my love for good music. I know that people use the same word I use here to justify violence, self-interest, and hatred. I cannot help but feel angry and disgusted when it is used for those ends, ends which seem so contrary to what the word means for me, ends that make me think someone has read the wrong script, mis-cast the character, not known what deeds God has done.

Theology and Theomythy

I was just reading Jamie Smith’s recent post on “Poetry and the End of Theology” over at his Fors Clavigera blog. His post reminded me of something I was thinking of several years ago when I was writing From Homer to Harry Potter.

Back in Homer’s time, the words λογος (logos) and μυθος (mythos) were near synonyms. Over time, they came to be distinguished from one another as meaning something like “an account in propositions” (logos) and “an account in stories” (mythos).

The word “logos” is one of the roots of our word “theology,” of course. Theology, then, means something like the attempt to discuss the divine in a logical and propositional manner. Which is all well and good, unless it begins to turn God into something we only analyze and never experience, about which we speak propositions but whose story never means much to us.

As a philosopher of religion, I think theology is important. The things we believe have consequences for us and for others. As one of my mentors, Ken Ketner, puts it, “Bad thinking kills people.” We know this from experience: people use theological ideas to justify all sorts of unethical behavior.

Nevertheless, theology is pretty dry stuff, and its very dryness has a genealogy and has consequences that we should be aware of. As Jamie puts it, some of the dryness of contemporary theology comes from a Cartesian anthropology that assumes that the most important part of us is that we are thinking things - things that care chiefly about propositions. If all we care about is getting our religion right, than this is the kind of theology we need, I suppose.

But is that what we are? Are we not also beings who live in the world, who live out stories, and who tell stories? Aren’t creativity and poetry and loveliness important to us as well? This got me thinking: maybe what we need is less theology and more theomythy. I’m not sure just what that would look like, but I think it might be worth a try. I’m interested in what you believe, sure. But I’m also interested in hearing your story.