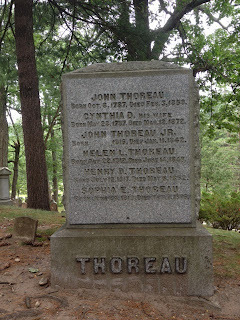

Thoreau

- Henry Bugbee, The Inward Morning. Don't try to read this book quickly, and if you're not prepared to do the hard work of thinking, move on and read something else. But if you're willing to read slowly and thoughtfully, this book can change your life. Bugbee was a philosophy professor and an angler.

- Henry David Thoreau, A Week On The Concord and Merrimack Rivers; The Maine Woods. Thoreau was an occasional angler, and an observer of anglers.

- Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac and the title essay in The River Of The Mother Of God, about unknown places. Leopold only writes a little about fish and fishing, but those occasional sentences about angling tend to be shot through with insight.

- John Muir, Nature Writings.

- John Steinbeck, Log From The Sea of Cortez. An apology for curiosity, in narrative form. One of my favorite books.

- Paul Errington, The Red Gods Call. Not brilliant writing, but a fascinating set of memoirs from a professor of biology who put himself through college as a trapper, and about how the Big Sioux River in South Dakota was his first real schoolroom. He talks a good deal about hunting and fishing and what he learned through encounters with animals.

- Kathleen Dean Moore, The Pine Island Paradox. Moore is an environmental philosopher who writes winsomely ans insightfully about what nature has meant to her family.

- Nick Lyons. Nick very kindly wrote the foreword to my book, and when I first got in touch with him about this I discovered he and I had lived only a few miles from each other in the Catskill Mountains for years. Sadly, by the time I discovered this I'd already moved away, and he was packing up to move to a new home, too. We both love the miles of small trout streams of those mountains, though. Nick has been a prolific writer and he has promoted a lot of great writing through his lifelong work as a publisher as well. Nick has a new book, Fishing Stories, just published in 2014.

- Norman Maclean, A River Runs Through It

- Ernest Hemingway, especially "Big Two-Hearted River" and the other Nick Adams stories

- James Prosek. Several books, including Trout: An Illustrated History; Early Love And Brook Trout; and Joe And Me: An Education In Fishing And Friendship

- Ted Leeson, The Habit Of Rivers

- Kurt Fausch’s new book, For The Love Of Rivers: A Scientist’s Journey. Brilliant writing by one of the world's leading trout biologists.

- Craig Nova, Brook Trout and the Writing Life. I also like his novels, and will recommend The Constant Heart.

- Christopher Camuto, who writes frequently for Trout Unlimited's journal, Trout.

- Ian Frazier, The Fish's Eye.

- Douglas Thompson, The Quest For The Golden Trout

- Izaak Walton, The Compleat Angler

- Dame Juliana Berners, The Boke Of St Albans, later editions of which contain A Treatyse of Fysshynge with an Angle, possibly authored by someone else.

- Nick Karas, Brook Trout (a nice collection of short works about brook trout, including some of my favorite stories)

- Lee Wulff

- Lefty Kreh

- John Gierach. Gierach has written a lot about angling, so it's not surprising that so many people mention him to me. Many of those mentions are positive, but some anglers mention his name with disgust. I haven't read much of his work, so I can't yet say why.

- David James Duncan, The River Why. This is a fun novel set in the Northwest, but it reminds me of the New Haven River in Vermont: there are some long dry stretches one has to plod through, but repeatedly one comes to depths that make the flatter, shallower parts worthwhile.

- Thomas McGuane, The Longest Silence.

- Bill McMillan

- Roderick Haig-Brown

- Mike Valla, The Founding Flies

- Michael Patrick O’Farrell, A Passion For Trout: The Flies And The Methods

- Peter Reilly, Lakes and Rivers of Ireland

- Derek Grzelewski, The Trout Diaries: A Year of Fly-fishing In New Zealand and The Trout Bohemia: Fly-Fishing Travels In New Zealand

- Eeva-Kaarina Aronen, Die Lachsfischerin. A novel set in Finland, about fly-fishing and fly-tying in the 18th century. The title translates as “The Salmon Fisherwoman”

- Ian Colin James, Fumbling With A Fly Rod (Scotland)

- Zane Grey, Tales of the Angler’s Eldorado: New Zealand

- Leslie Leyland Fields, Surviving the Island of Grace; and Hooked! Fields and her family are commercial fishers in Alaska, and her writing comes recommended to me from a number of sources.

- Sheridan Anderson, The Curtis Creek Manifesto

- Harry Middleton, The Earth Is Enough: Growing Up In A World Of Fly-fishing, Trout, And Old Men (Memoir)

- Paul Schullery, Royal Coachman: The Lore And Legends of Fly-fishing

- Gordon MacQuarrie

- Patrick McManus

- Vince Marinaro, The Game of Nods

- Rich Tosches, Zipping My Fly

- Robert Lee, Guiding Elliott

- Peter Heller, The Dog Stars (novel)

- Paul Quinnett, Pavlov’s Trout

- Dana S. Lamb Where The Pools Are Bright And Deep; Bright Salmon and Brown Trout

- John Shewey, Mastering The Spring Creeks

- Ernest Schweibert, Death of a Riverkeeper; A River For Christmas

- Richard Louv, Fly-fishing for Sharks: An Angler’s Journey Across America

- John Voelker’s short story “Murder”

- Dave Ames, A Good Life Wasted, Or 20 Years As A Fishing Guide

- Craig Childs, The Animal Dialogues, especially the chapter “Rainbow Trout”

- Randy Nelson, Poachers, Polluters, and Politics: A Fishery Officer’s Career

- Anders Halverson, An Entirely Synthetic Fish: How Rainbow Trout Beguiled America And Overran The World

- Thomas McGuane, A Life In Fishing

- Bob White

- Robert Ruark

- Tom Meade

- Hank Patterson

- This too is related to technology, of course. If the class is focused on video screens, then all the chairs will face the screens, and the classroom might even be structured like a theater. Etymologically, "theater" means something like "a place of gazing," and theaters tend to encourage people to gaze. Sometimes this can work against other activities, like colloquy, small-group interaction, and really anything that involves students moving from one place to another.

- If that last sentence made you ask,"But why do you want your students to move from one place to another?" then you see that we have some pretty strong presuppositions about how education should happen: students should sit and listen, teachers should stand and lecture. This communicates something about authority, and at times that's helpful. But it can also invite students to lean back into passivity, and to assume they have no role in their own education.

- The furniture in classrooms tells us how people are to behave, because it has been made and purchased by people who had in mind some idea of how students should behave. Most wrap-around desks are made for right-handed people, for instance. And most classroom desks I've seen expect students to sit upright, at attention, with a book open in front of them. I really don't like those desks, and I feel trapped when I sit in them. I wonder sometimes how they make my students feel. I wish we had fewer chairs and more sofas. Maybe a fireplace, or some tables with glasses of water, and ashtrays on them. I suppose I wish I could teach in pubs or ratskellers, which are, after all, places consciously designed for people to meet and discuss what most matters to them, informally, passionately, amicably.

- Classrooms that privilege video screens tend to undervalue natural light and windows. I am reminded of Emerson's reflection on a boring sermon he once heard. Emerson wrote, in his Divinity School Address, that while the minister droned on, Emerson looked out the window at the falling snow, which, he proclaimed, preached a better sermon than the minister. I have no doubt that nature can often give a better lecture than I can.

∞

2) Second, fill your toolbox—and your community’s toolbox—with bear poop. This is an inside reference my students will understand by the end of the semester, but I'll fill you in briefly: I take the time when I am in the wild to look at animal scat, because it is often a picture of what food is available to the animals, and that, in turn, is a picture of the problems the environment is facing. Paying attention to scat over time gives you a long-term picture of changes to the environment. Poop is a tool that is free, that is right in front of you, and that is easy to overlook as unimportant or distasteful. Bear poop that is full of salmon bones tells me one story; bear poop that is full of berries tells me another. I don't literally fill my toolbox with bear poop, but paying attention to negligible things like bear poop gives me new tools I wouldn't have otherwise. What does this mean for us?

Wicked Problems in Environmental Policy

When I first started teaching environmental philosophy courses I used anthologies of helpful articles for my core readings. These included articles about topics ranging from environmental ethics and philosophy of nature to animal rights, land ethics, and pollution.

The more I read, the more I realized how hard it is to do more than a simple survey of problems in a single semester. From early on, I started adding narratives to my classes, using texts by people like Wendell Berry, Aldo Leopold, Rachel Carson, Henry Thoreau, Kathleen Dean Moore, and Vandana Shiva. I've also included sacred texts and poems from around the world, because while many of those narratives and poems don't solve the problems, the form of writing they use makes them a flowing spring of renewable thought-provocation.

Recently I've taken on an even broader approach to teaching environmental humanities courses by designing a course I call "How To Begin To Solve 'Wicked Problems' In Environmental Policy."

I won't explain everything here, because the topic is too big to explain in detail now, but I will try to explain what I mean by the title of the course.

The previous sentence is a picture of what the course is like: there's too much to cover all at once; there are too many elements to explain to do them all justice in a short space; so it's often more helpful to begin the process and to keep it before you as an ongoing matter than to treat it as a simple problem to be solved with a simple solution.

This is the nature of "wicked problems," after all. It's not that the problems are wicked or evil, but they are immensely complex, with many changeable parts or situations, and any solution that is offered will change the situation. An example might help to illustrate what I mean. Let's consider world poverty.

If we take poverty to mean simply the lack of funds on the part of the impoverished, then it is a simple problem to solve (even if it isn't an easy one.) All you have to do is find out how much money the poor lack, and give it to them. If poverty were simply a lack of funds, then filling that lack with funds would be the solution. But this solution fails to ask what caused the lack of funds in the first place, or why it matters. And it fails to acknowledge that handing over money changes the situation into which the money is given. Economists know that economic predictions are not a precise science. There are simply too many factors at play in human economic systems. As the 17th-century philosopher Mary Astell put it, "single medicines are too weak to cure such complicated distempers." [1] Some medicines have side effects, after all, and the same is true in economics, and in many other disciplines.

So how do I teach this course? I start with some problems I understand too poorly and some narratives that I know will be incomplete, focusing on two places where I teach and do research: Guatemala's Petén Department, and the headwaters of the Bristol Bay region of Alaska. In both cases, there is competition for certain resources, and the use of one resource can threaten or permanently impair other resources.

I don't expect my students can solve these problems for other people, but they are problems I've come to know more and more intimately over years of firsthand experience of the regions in question. So I tell my students stories about those places, and I try to introduce them (often by video calls) to people who work in those places. I want my students to get to know as many different stakeholders as possible, and to hear their stories in the context of those peoples' lives.

You might justifiably ask: if I don't expect my students to solve the problems, and if I myself don't have the solutions, what justifies teaching such a course? My answer is, first, that it is better to try than not to try, and second, that in looking at problems in which we don't feel a personal investment we can often learn to tackle the problems that are closer to home.

There's an ethical and political upside to this, too: once you see that certain problems are "wicked problems," you can start to see the ways that policy-touting charlatans try to pull the wool over your eyes. It is a very old political trick to win votes by claiming that wicked problems are simple ones, and that only you or your party can see the simple solution. This gives a strange comfort to voters who have been perplexed by complexity, and that comfort wins votes on the cheap, at the expense of humility, neighborly care, mutual struggle, bipartisan collaboration, and seriousness of thought.

I have more to say about this - some of it no doubt will be mistaken - but for now I'll wrap up this piece with a rough outline of what I propose to my students as a way to begin to solve wicked problems in environmental policy. Here it is:

1) First, identify the community of stakeholders.

a. Do so for their perspectives, for their interests, and for their tools.

b. Ask: Who are the stakeholders?

i. Go beyond the financial stakeholders or stockholders.

ii. Include everyone who affects, or is affected by, the policy under consideration.

c. Remember Charles Peirce’s idea: science is the work of a community, not of an individual.

d. Make concept maps, and use other kinds of visualizations of the problems.

i. This is a way of utilizing a broad range of tools. Don’t just use the tools others tell you are relevant; include the arts and the sciences alike.

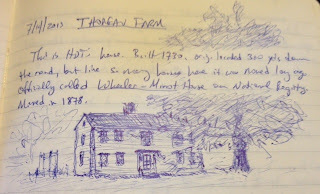

ii. Drawing and sketching pictures will help you to see better. As Louis Agassiz said, “the pencil is one of the best eyes.” It is often better than a camera.

iii. Music, literature, poetry, and the visual arts may be just as helpful as the tools offered by STEM fields and policy-making professions like law.

iv. If you include the arts, you wind up including the artists; similarly, if you exclude the arts, you exclude the wisdom and insight of the artists.

v. Include ordinary daily practices. Learn to fish, even if you don’t plan to fish. Hike in the woods, even if you don’t like the outdoors. These are, in a way, practices of paying attention to the world.

e. Include other voices and texts in the conversation, not just the shareholders, but all the stakeholders.

f. Define “stakeholders” as broadly as you can. Include a community across generations. Include the departed and the not-yet-born if possible.

i. Traditions might be full of wisdom, so don’t ignore them, especially if they are specific to a place. Traditions may be inarticulate wisdom that is tested by time.

ii. Plan for seven generations. I sometimes think of this as the difference between planting those crops you will harvest this year and planting hardwood trees so that they will be old-growth trees long after you are dead. Humans – and other species – need both kinds of plants.

a. Do so for their perspectives, for their interests, and for their tools.

b. Ask: Who are the stakeholders?

i. Go beyond the financial stakeholders or stockholders.

ii. Include everyone who affects, or is affected by, the policy under consideration.

c. Remember Charles Peirce’s idea: science is the work of a community, not of an individual.

d. Make concept maps, and use other kinds of visualizations of the problems.

i. This is a way of utilizing a broad range of tools. Don’t just use the tools others tell you are relevant; include the arts and the sciences alike.

ii. Drawing and sketching pictures will help you to see better. As Louis Agassiz said, “the pencil is one of the best eyes.” It is often better than a camera.

iii. Music, literature, poetry, and the visual arts may be just as helpful as the tools offered by STEM fields and policy-making professions like law.

iv. If you include the arts, you wind up including the artists; similarly, if you exclude the arts, you exclude the wisdom and insight of the artists.

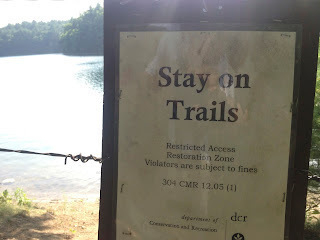

v. Include ordinary daily practices. Learn to fish, even if you don’t plan to fish. Hike in the woods, even if you don’t like the outdoors. These are, in a way, practices of paying attention to the world.

e. Include other voices and texts in the conversation, not just the shareholders, but all the stakeholders.

f. Define “stakeholders” as broadly as you can. Include a community across generations. Include the departed and the not-yet-born if possible.

i. Traditions might be full of wisdom, so don’t ignore them, especially if they are specific to a place. Traditions may be inarticulate wisdom that is tested by time.

ii. Plan for seven generations. I sometimes think of this as the difference between planting those crops you will harvest this year and planting hardwood trees so that they will be old-growth trees long after you are dead. Humans – and other species – need both kinds of plants.

|

| Bear scat along a salmon river, Katmai Preserve, Alaska |

2) Second, fill your toolbox—and your community’s toolbox—with bear poop. This is an inside reference my students will understand by the end of the semester, but I'll fill you in briefly: I take the time when I am in the wild to look at animal scat, because it is often a picture of what food is available to the animals, and that, in turn, is a picture of the problems the environment is facing. Paying attention to scat over time gives you a long-term picture of changes to the environment. Poop is a tool that is free, that is right in front of you, and that is easy to overlook as unimportant or distasteful. Bear poop that is full of salmon bones tells me one story; bear poop that is full of berries tells me another. I don't literally fill my toolbox with bear poop, but paying attention to negligible things like bear poop gives me new tools I wouldn't have otherwise. What does this mean for us?

a. Identify the community’s tools, perspectives, and skills, and seek to integrate them into a tool-wielding community.

b. See the problem as broadly as you can. We tend to frame problems based on our perspective, so do what you can to gain the perspectives of others.

Emerson: move your body so that your eyes see the world from a different angle.

c. Try to gain as many tools as you can

d. Value experience and first-hand knowledge

i. Go underwater – that is, look at the world in new and unfamiliar ways, from unfamiliar vantage points.

ii. Travel – get to know the world differently, and get to know how others know the world. Don't just do tourism, but saunter, as Thoreau puts it.

iii. Learn the languages you can – even a little bit will make a difference. Words are tools, and they are lenses through which to see the world anew.

iv. Study “unnecessary” knowledge, and not just the knowledge others tell you is necessary – don’t let others tell you what tools are worth gaining.

v. Foster your curiosity. Don’t let it die of neglect.

e. Engage in labs, even in the Humanities – learn experientially.

3) Third, have what Peirce calls “regulative ideals”

3) Third, have what Peirce calls “regulative ideals”

a. Aim high, and have a direction. But

b. Recognize that the direction will change; this is like taking bearings while navigating. You have to keep adjusting as you move and as you discover the landscape

4) Fourth, don’t expect perfection

4) Fourth, don’t expect perfection

a. and don’t expect ultimate solutions. Expect that truly ‘wicked’ problems will continue to be problems, and that they will continue to change and to spawn new problems. Such is life.

b. Instead, expect meliorism, growth, improvement

c. Peirce uses some odd words to describe all this: tychism, synechism, agapism: chance, continuity, love. Someday, look these up, or ask me to define them for you. Vocabulary is a powerful tool.

5) Fifth, do expect growth, and strive to cultivate good things. This is the work of ethics.

6) Sixth, do expect to be part of a community that continues to work on the problems for a long time.

7) And seventh, don’t give up!

5) Fifth, do expect growth, and strive to cultivate good things. This is the work of ethics.

6) Sixth, do expect to be part of a community that continues to work on the problems for a long time.

7) And seventh, don’t give up!

Of course it is possible to solve environmental policy problems apart from a community; once you’re no longer a part of a community, “policy” takes on a simpler meaning, and so does “environmental.” But merely redefining words—or merely divorcing yourself from a situation—doesn’t solve the problem. Rather, those decisions only blind us to the problem. This is satisfying our own irritation rather than satisfying the needs generated by the actual problem.

*****

[1] Mary Astell, A Serious Proposal to the Ladies, Sharon L. Jansen, ed. (Steilacoom, WA: Saltar's Point Press, 2014) p.65.

∞

A Pretty Good Year

Last year was a pretty good year. Or at least, what I remember of it was pretty good.

As my regular readers know, I'm a professor of philosophy and classics, and I teach a wide range of classes. (You can click on the "Teaching" link above to see a sampling of the courses I teach.)

Often people assume that means I wear tweed and a bowtie and that I spend my time in classrooms talking about old books. All that is true, but it's only a part of what I do.

In fact, most of my favorite classrooms are outdoors, where I'm likely to be found wearing jeans and hiking boots, a parka, or a wetsuit and snorkel.

Over the last dozen years or so my teaching and research have tended towards the environmental humanities. Think of this as the merging of the humanities side of the liberal arts with a close observation of the natural world. I consider my work to be a continuation of the work that Thales and Aristotle did when they paid close attention to animals on the ground and to the skies above, and of the work of Peirce, Thoreau, and Bugbee, all of whom let a rising trout or a solar eclipse provoke philosophical reflection.

While I don't work in an indoor laboratory, I think that education is not about the imparting of information or the filling of an empty vessel with ideas. Education is the kindling of a fire, as Plutarch wrote. And that fire is kindled by the kinds of experiences that we get in labs, art studios, shared meals, liturgies, study travel, and seminars. Lecture halls are a fine place to discuss environmental policy, to be sure. But so is a prairie, especially when you're waiting for water to boil on your camp stove, and watching the sun's beams break over the horizon and melt a light frost on your tent.

When I'm at home, I like to take my classes outside to sit under trees on campus. In the fall, I try to bring my Ancient Philosophy students camping in the Badlands of South Dakota where we can view the stars far from urban glow. Most Januaries, my students and I are in the subtropical forests of Guatemala and on a barrier island in Belize, studying ecology and culture. I rarely take a spring break, since I usually take that week to teach a course in Greece. Last summer I started teaching a class on trout and salmon in Alaska.

Those are all beautiful, memorable places, but I don't visit them as a tourist. I go to these places because I want my students to understand what is at stake when we talk about environmental regulations and practices. I want them to meet displaced people whose permafrost islands are melting or whose forests are being burned down for meager cropland. I want them to see the disappearing mangroves so that they can consider the full cost of seafood. When they stay in homes in Guatemala, my students will meet people who can never again be a mere abstraction; after we return, my students will know that the people struggling to cross borders are not nameless, faceless strangers, but people who are looking for ways to feed those they love.

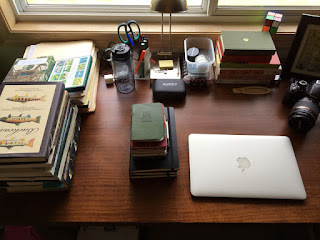

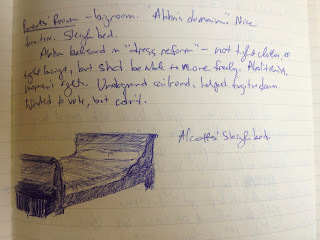

A little less than a year ago I was finishing up a year that had brought me to all these places. I taught in the South Dakota Badlands, in Central America, in Greece, and in Alaska. Along the way, I had begun studying environmental law at Vermont Law School as a way of enhancing my teaching and my research. It was a good year, and as August was winding down, my desk was covered with field notebooks full of observations from Alaska and Guatemala, ready to be written up. My field notes are usually accompanied by thousands of photographs, and hundreds of sketches. I began the fall semester last year ready to teach, and ready to write.

And then I wound up in the hospital with some serious injuries. Those injuries put a sudden stop to all my teaching last fall, and for a long time I lost most of my ability to write. (I'll try to write more about the injuries and my subsequent disabilities later; it's not an easy thing to write about yet.)

Now, as this summer hastens towards the beginning of another school year, I am able to look back on last year with a sense of good fortune - albeit mixed with one very bad day and its long-term consequences. Physically, I'm regaining my flexibility and strength, a little at a time. I'm not where I was a year ago, and I may never be there again, but I'm alive and able to walk, so I'll count that in the "win" column of my life's scorecard. Intellectually, most people seem to think I'm doing fine, so I'll also count that as a win. Although it left me exhausted each day, I was able to teach again this spring, and I plan to be back in my classrooms (Deo volente!) this fall.

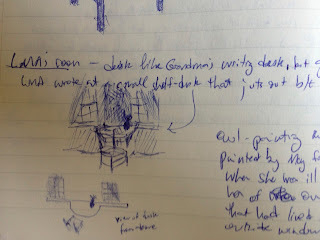

But here are these field notebooks, and hundreds of unedited pages on my hard drive. It was my habit to write daily. Over the last year, recovering from a brain injury has made it hard to write more than a few sentences at a time.

This morning I was looking at some of my pictures from my research in the Arctic last summer, and I was hit with a feeling of loss. Those photos and those notes should be a book by now, and perhaps several articles and book chapters, too. Instead, over the last year, as I have waited for my body and brain to heal, and as I struggled to do my teaching, I had no strength to write.

It feels funny to say that, but perhaps I am not alone in finding that a brain injury can be slow to heal and extremely tiring. I don't say that to get your sympathy. I am blessed with a very supportive community and an amazing wife who somehow has kept our life together and nursed me through my healing process. I'm fortunate. But if you've read this far, you might consider whether there are others around you who look like they're doing well physically but who might be nursing invisible wounds or who might be struggling to cope with invisible disabilities. This past year has given me a new perspective on that by making me aware of my own disabilities, most of which you won't notice if you see me at the gym or in one of my classrooms.

I might not be able to write another book yet, so for now, here's my plan: I'll write a little at a time. Thankfully, I've got my notes, sketches, and photos. I'll start with them.

If you're curious about how a professor of philosophy and classics does research and writing about nature - and how he works to recover from a serious brain injury - you might check out some of my recent publications. My book Downstream is the result of eight years of field research on the ecology of the Appalachians, with a focus on brook trout. On this blog you'll also find my recently published poem, "Sage Creek," which might give you a glimpse of my ancient philosophy class camping and stargazing in the Badlands. Or feel free to look at my photos on Instagram. Even when I can't teach in the field, I can still wander my garden with a hand lens and camera.

As my regular readers know, I'm a professor of philosophy and classics, and I teach a wide range of classes. (You can click on the "Teaching" link above to see a sampling of the courses I teach.)

Often people assume that means I wear tweed and a bowtie and that I spend my time in classrooms talking about old books. All that is true, but it's only a part of what I do.

In fact, most of my favorite classrooms are outdoors, where I'm likely to be found wearing jeans and hiking boots, a parka, or a wetsuit and snorkel.

Over the last dozen years or so my teaching and research have tended towards the environmental humanities. Think of this as the merging of the humanities side of the liberal arts with a close observation of the natural world. I consider my work to be a continuation of the work that Thales and Aristotle did when they paid close attention to animals on the ground and to the skies above, and of the work of Peirce, Thoreau, and Bugbee, all of whom let a rising trout or a solar eclipse provoke philosophical reflection.

While I don't work in an indoor laboratory, I think that education is not about the imparting of information or the filling of an empty vessel with ideas. Education is the kindling of a fire, as Plutarch wrote. And that fire is kindled by the kinds of experiences that we get in labs, art studios, shared meals, liturgies, study travel, and seminars. Lecture halls are a fine place to discuss environmental policy, to be sure. But so is a prairie, especially when you're waiting for water to boil on your camp stove, and watching the sun's beams break over the horizon and melt a light frost on your tent.

When I'm at home, I like to take my classes outside to sit under trees on campus. In the fall, I try to bring my Ancient Philosophy students camping in the Badlands of South Dakota where we can view the stars far from urban glow. Most Januaries, my students and I are in the subtropical forests of Guatemala and on a barrier island in Belize, studying ecology and culture. I rarely take a spring break, since I usually take that week to teach a course in Greece. Last summer I started teaching a class on trout and salmon in Alaska.

Those are all beautiful, memorable places, but I don't visit them as a tourist. I go to these places because I want my students to understand what is at stake when we talk about environmental regulations and practices. I want them to meet displaced people whose permafrost islands are melting or whose forests are being burned down for meager cropland. I want them to see the disappearing mangroves so that they can consider the full cost of seafood. When they stay in homes in Guatemala, my students will meet people who can never again be a mere abstraction; after we return, my students will know that the people struggling to cross borders are not nameless, faceless strangers, but people who are looking for ways to feed those they love.

A little less than a year ago I was finishing up a year that had brought me to all these places. I taught in the South Dakota Badlands, in Central America, in Greece, and in Alaska. Along the way, I had begun studying environmental law at Vermont Law School as a way of enhancing my teaching and my research. It was a good year, and as August was winding down, my desk was covered with field notebooks full of observations from Alaska and Guatemala, ready to be written up. My field notes are usually accompanied by thousands of photographs, and hundreds of sketches. I began the fall semester last year ready to teach, and ready to write.

|

| Field notes. A picture of some of the work I do when I'm inside, and not teaching; or, if you like, a picture of my desk as I recover from my injuries. I have a lot of catching up to do. |

And then I wound up in the hospital with some serious injuries. Those injuries put a sudden stop to all my teaching last fall, and for a long time I lost most of my ability to write. (I'll try to write more about the injuries and my subsequent disabilities later; it's not an easy thing to write about yet.)

Now, as this summer hastens towards the beginning of another school year, I am able to look back on last year with a sense of good fortune - albeit mixed with one very bad day and its long-term consequences. Physically, I'm regaining my flexibility and strength, a little at a time. I'm not where I was a year ago, and I may never be there again, but I'm alive and able to walk, so I'll count that in the "win" column of my life's scorecard. Intellectually, most people seem to think I'm doing fine, so I'll also count that as a win. Although it left me exhausted each day, I was able to teach again this spring, and I plan to be back in my classrooms (Deo volente!) this fall.

But here are these field notebooks, and hundreds of unedited pages on my hard drive. It was my habit to write daily. Over the last year, recovering from a brain injury has made it hard to write more than a few sentences at a time.

This morning I was looking at some of my pictures from my research in the Arctic last summer, and I was hit with a feeling of loss. Those photos and those notes should be a book by now, and perhaps several articles and book chapters, too. Instead, over the last year, as I have waited for my body and brain to heal, and as I struggled to do my teaching, I had no strength to write.

It feels funny to say that, but perhaps I am not alone in finding that a brain injury can be slow to heal and extremely tiring. I don't say that to get your sympathy. I am blessed with a very supportive community and an amazing wife who somehow has kept our life together and nursed me through my healing process. I'm fortunate. But if you've read this far, you might consider whether there are others around you who look like they're doing well physically but who might be nursing invisible wounds or who might be struggling to cope with invisible disabilities. This past year has given me a new perspective on that by making me aware of my own disabilities, most of which you won't notice if you see me at the gym or in one of my classrooms.

I might not be able to write another book yet, so for now, here's my plan: I'll write a little at a time. Thankfully, I've got my notes, sketches, and photos. I'll start with them.

If you're curious about how a professor of philosophy and classics does research and writing about nature - and how he works to recover from a serious brain injury - you might check out some of my recent publications. My book Downstream is the result of eight years of field research on the ecology of the Appalachians, with a focus on brook trout. On this blog you'll also find my recently published poem, "Sage Creek," which might give you a glimpse of my ancient philosophy class camping and stargazing in the Badlands. Or feel free to look at my photos on Instagram. Even when I can't teach in the field, I can still wander my garden with a hand lens and camera.

∞

Thoreau on Liberal Education, Wealth, and Freedom

“We seem to have forgotten that the expression "a liberal education" originally meant among the Romans one worthy of free men; while the learning of trades and professions by which to get your livelihood merely, was considered worthy of slaves only. But taking a hint from the word, I would go a step further and say, that it is not the man of wealth and leisure simply, though devoted to art, or science, or literature, who, in a true sense, is liberally educated, but only the earnest and free man.”

-- Henry David Thoreau, "The Last Days of John Brown"

∞

Liberal Education And Freedom

"We seem to have forgotten that the expression "a liberal education" originally meant among the Romans one worthy of free men; while the learning of trades and professions by which to get your livelihood merely, was considered worthy of slaves only. But taking a hint from the word, I would go a step further and say, that it is not the man of wealth and leisure simply, though devoted to art, or science, or literature, who, in a true sense, is liberally educated, but only the earnest and free man."

H.D. Thoreau, "The Last Days of John Brown"

∞

I'm preparing to teach a course on ecology and nature writing this summer in Alaska. One of the keys to becoming a good writer is to read good writing, so I've been asking for book recommendations that might help me prepare for my course.

The focus of the course will be the char species of Alaska. These species, all members of the genus salvelinus, are commonly thought of as trout. Brook trout and lake trout are both char, as are Dolly Vardens and arctic char.

These are beautiful fish. I think many anglers love them simply because they are so beautiful to look at. When I pull one from the water I am immediately torn between wanting to hold this precious thing closely and the urge to release it immediately, before my coarse hands pollute its loveliness. The name "char" might come from Celtic roots, like the Gaelic cear, meaning "blood." They are more multi-hued than rainbow trout. The red on their sides and fins catches the eye and holds the gaze.

Over the years I spent researching and writing my own book on brook trout, I did a lot of reading. Some books call me back again and again, like Henry Bugbee's The Inward Morning and Steinbeck's Log From The Sea of Cortez. Neither one is chiefly about fly-fishing or about trout, but they're both written in a way that makes me re-think how I view the world. And they do both talk a good deal about fish, and fishing.

Of course there are the classics of fly-fishing, too. Still, as I've asked for suggestions, I've been surprised by how many books there are that I haven't read or haven't even heard of. Just how many books about fish and fishing do we need? Are there really so many stories to tell?

If the point of writing books about fish is to give techniques, or data, then we don't need many at all. But stories about fish and fishing are rarely about the taking of fish. More often they are about the states of mind that open up as we prepare to enter the water, or as we stand there in the river. Fishing is to such states of consciousness what kneeling is to prayer; the posture is perhaps not essential, but it is a bodily gesture that does something to prepare us to be open to a certain kind of experience. I won't belabor this point. Read my book if you really want me to go on about fishing and philosophy. For now, let me present some of my recommendations, plus the recommendations I've received:

On Nature

I teach environmental philosophy and ecology, so I begin with some orienting books.

Some Favorites

Classics

These have been recommended time and again. I'm not sure many people ever actually read the first two, though they become prized volumes in the libraries of anglers around the world.

Most Recommended

Fly-Tying

Places

One reason why there is so much writing about fishing is that fishers tend to be students of particular places. Yes, some people fish by indiscriminately approaching water and drowning hooked worms therein, but experience tends to cure most young anglers of that method. Fishing puts us into contact with what we cannot see (or cannot see well) under the water; experienced anglers learn to read the signs above the water and the place itself. We return to the same place as we return to beloved passages in books or to favorite songs, to know them better through repetition.

Other Frequent Recommendations

If I talk to a group of anglers about books for long enough, one or more of these will eventually be mentioned. Stylistically and in terms of content, they're quite different, but they all seem to speak to important moods and thoughts of anglers.

Other Recommendations

Most of these I don't know at all, so I'm not recommending them, just mentioning them. Of course, if you have more recommendations (or corrections), please feel free to add them to the comments section, below.

I'll conclude with a few other recommendations. First, when I've asked for recommendations about texts, a handful of people tell me "Tenkara." This isn't a text, but a kind of rod, and a method of fly-fishing. And yet people continue to say that word to me when I ask for texts. Why is that? I have a few guesses: there isn't a lot written about tenkara, but people who practice it have come to love its simplicity and grace. I'm not a tenkara fisher (yet) but I'm eager to learn. I have a feeling that tenkara, like so many spiritual practices or like some martial arts, is something that makes people feel they way great writing makes us feel: in it we transcend the immediacy of our environment.

Along those lines, one commenter on Facebook said this to me about my students: "Give them [a] fly rod and a stream and let them write [their] own story." There is wisdom here. It is one thing to read about waters, and quite another to enter the waters on one's own feet. Even so, I think it's important and wise to learn from those who've gone before us, too.

If you're interested in seeing some of my other book recommendations, have a look at this, this, and this.

Recommended Reading: Fly-Fishing and Trout

|

The focus of the course will be the char species of Alaska. These species, all members of the genus salvelinus, are commonly thought of as trout. Brook trout and lake trout are both char, as are Dolly Vardens and arctic char.

These are beautiful fish. I think many anglers love them simply because they are so beautiful to look at. When I pull one from the water I am immediately torn between wanting to hold this precious thing closely and the urge to release it immediately, before my coarse hands pollute its loveliness. The name "char" might come from Celtic roots, like the Gaelic cear, meaning "blood." They are more multi-hued than rainbow trout. The red on their sides and fins catches the eye and holds the gaze.

Over the years I spent researching and writing my own book on brook trout, I did a lot of reading. Some books call me back again and again, like Henry Bugbee's The Inward Morning and Steinbeck's Log From The Sea of Cortez. Neither one is chiefly about fly-fishing or about trout, but they're both written in a way that makes me re-think how I view the world. And they do both talk a good deal about fish, and fishing.

|

| Mayfly on my reel. Summer 2014, Maine. |

If the point of writing books about fish is to give techniques, or data, then we don't need many at all. But stories about fish and fishing are rarely about the taking of fish. More often they are about the states of mind that open up as we prepare to enter the water, or as we stand there in the river. Fishing is to such states of consciousness what kneeling is to prayer; the posture is perhaps not essential, but it is a bodily gesture that does something to prepare us to be open to a certain kind of experience. I won't belabor this point. Read my book if you really want me to go on about fishing and philosophy. For now, let me present some of my recommendations, plus the recommendations I've received:

On Nature

I teach environmental philosophy and ecology, so I begin with some orienting books.

Some Favorites

Classics

These have been recommended time and again. I'm not sure many people ever actually read the first two, though they become prized volumes in the libraries of anglers around the world.

Most Recommended

Fly-Tying

Places

One reason why there is so much writing about fishing is that fishers tend to be students of particular places. Yes, some people fish by indiscriminately approaching water and drowning hooked worms therein, but experience tends to cure most young anglers of that method. Fishing puts us into contact with what we cannot see (or cannot see well) under the water; experienced anglers learn to read the signs above the water and the place itself. We return to the same place as we return to beloved passages in books or to favorite songs, to know them better through repetition.

Other Frequent Recommendations

If I talk to a group of anglers about books for long enough, one or more of these will eventually be mentioned. Stylistically and in terms of content, they're quite different, but they all seem to speak to important moods and thoughts of anglers.

Other Recommendations

Most of these I don't know at all, so I'm not recommending them, just mentioning them. Of course, if you have more recommendations (or corrections), please feel free to add them to the comments section, below.

I'll conclude with a few other recommendations. First, when I've asked for recommendations about texts, a handful of people tell me "Tenkara." This isn't a text, but a kind of rod, and a method of fly-fishing. And yet people continue to say that word to me when I ask for texts. Why is that? I have a few guesses: there isn't a lot written about tenkara, but people who practice it have come to love its simplicity and grace. I'm not a tenkara fisher (yet) but I'm eager to learn. I have a feeling that tenkara, like so many spiritual practices or like some martial arts, is something that makes people feel they way great writing makes us feel: in it we transcend the immediacy of our environment.

Along those lines, one commenter on Facebook said this to me about my students: "Give them [a] fly rod and a stream and let them write [their] own story." There is wisdom here. It is one thing to read about waters, and quite another to enter the waters on one's own feet. Even so, I think it's important and wise to learn from those who've gone before us, too.

*****

If you're interested in seeing some of my other book recommendations, have a look at this, this, and this.

∞

Interview on SD Public Radio

Karl Gehrke interviewed me on SD Public Radio today about my new book. We talk about the book, brook trout, fly-fishing, hunting, raising children, and a handful of other topics with occasional nods to Heidegger and Bugbee, Kathleen Dean Moore, Scott Russell Sanders, and, of course, Thoreau.

Click here to listen to the whole interview.

Click here to listen to the whole interview.

∞

Giving Our Prayers Feet

The American scientist and philosopher Charles Peirce described belief as an idea you are prepared to act on. If you say you believe something but you are not prepared to act on it, you probably don't really believe it in any meaningful sense of that word.

Of course, there might be a number of ways in which we might act on our beliefs.

What about prayer? Could praying be a kind of action?

It depends.

Philosopher and atheist Daniel Dennett once described prayer as a waste of time. I mean literally a waste of time. If you're praying, he said, you're not engaged in useful activity. When he was ill, someone offered to pray for him. His reply:

On the other hand, as I've argued before, prayer might be essential to other kinds of action.

Giving our money and time is generally a good thing, I think, but I think the giving becomes deeper still when we do as Thoreau urged in Walden: don't just give your money, but give yourself. In other words, if you've begun by dumping water on your head for an ALS icebucket challenge, great. Now deepen that giving by making it part of who you are.

If you decide to do that, prayer - or something like it, I don't care what you call it - can make a big difference. Here's what I mean: giving to charities can be automated, so you can do it without thinking about it. Set up an automatic bank transfer each month and you can give to as many charities as you can afford, without putting much of yourself in it. But if you make those philanthropies and missions the intentional object of your thought for part of each day, you might find that you begin to care a lot more about the cause and the people involved.

If praying is the act of giving some of your time to bring together the world's greatest needs and your greatest hopes, then prayer might be the most important thing we can do. Too often we allow ourselves to divorce others' needs from our hopes, and then the needs of others become allied with our fears.

This is one reason why I respond to the news each day with prayer. Sometimes my prayers are simply Kyrie eleison, "Lord, have mercy." Because sometimes that's all I've got when my heart and mind are overwhelmed. But if that's all I've got, then it will be my widow's mite, and I'll give it. By the way, this has the added effect of making me worry less without taking away my desire to act for goodness and justice.

(My friend Anna Madsen has a short, funny, and helpful piece about just that, by the way. Check it out here.)

All of this was inspired by a moving Facebook post by an alumnus of my college, Caleb Rupert. Caleb is a thoughtful and creative man, and though I don't know him well, he strikes me as a good egg and as someone who wants to do the best he can in this life. Here's what he shared on his page:

I asked Caleb if I could share his words here. His reply is just as good as his original post. He said I could post his words, provided I include some links to local food shelves, soup kitchens, and homeless shelters. I love that.

So I will ask that if you share this post, you do the same thing by posting a link to at least one organization in *your* community that helps the homeless. In that way, let us make our prayers effective to the best of our ability, and may they rise to whatever heaven may be.

Here are my links for Sioux Falls, South Dakota. Please consider volunteering your time, giving your money, and remembering them and the people they serve in your prayers. And as you do so, may your prayers grow feet, and begin to change the world.

The Banquet

Union Gospel Mission

St Francis House

Of course, there might be a number of ways in which we might act on our beliefs.

What about prayer? Could praying be a kind of action?

It depends.

Philosopher and atheist Daniel Dennett once described prayer as a waste of time. I mean literally a waste of time. If you're praying, he said, you're not engaged in useful activity. When he was ill, someone offered to pray for him. His reply:

Surely it does the world no harm if those who can honestly do so pray for me! No, I'm not at all sure about that. For one thing, if they really wanted to do something useful, they could devote their prayer time and energy to some pressing project that they can do something about. (emphasis added)I agree with him that if prayer keeps us from doing what we can to alleviate the suffering of the world, we're probably using our time poorly.

On the other hand, as I've argued before, prayer might be essential to other kinds of action.

Giving our money and time is generally a good thing, I think, but I think the giving becomes deeper still when we do as Thoreau urged in Walden: don't just give your money, but give yourself. In other words, if you've begun by dumping water on your head for an ALS icebucket challenge, great. Now deepen that giving by making it part of who you are.

If you decide to do that, prayer - or something like it, I don't care what you call it - can make a big difference. Here's what I mean: giving to charities can be automated, so you can do it without thinking about it. Set up an automatic bank transfer each month and you can give to as many charities as you can afford, without putting much of yourself in it. But if you make those philanthropies and missions the intentional object of your thought for part of each day, you might find that you begin to care a lot more about the cause and the people involved.

If praying is the act of giving some of your time to bring together the world's greatest needs and your greatest hopes, then prayer might be the most important thing we can do. Too often we allow ourselves to divorce others' needs from our hopes, and then the needs of others become allied with our fears.

This is one reason why I respond to the news each day with prayer. Sometimes my prayers are simply Kyrie eleison, "Lord, have mercy." Because sometimes that's all I've got when my heart and mind are overwhelmed. But if that's all I've got, then it will be my widow's mite, and I'll give it. By the way, this has the added effect of making me worry less without taking away my desire to act for goodness and justice.

(My friend Anna Madsen has a short, funny, and helpful piece about just that, by the way. Check it out here.)

All of this was inspired by a moving Facebook post by an alumnus of my college, Caleb Rupert. Caleb is a thoughtful and creative man, and though I don't know him well, he strikes me as a good egg and as someone who wants to do the best he can in this life. Here's what he shared on his page:

I'm standing at the bus stop and on the corner is a homeless woman. A kind looking black gentleman is walking by and nearly walks past her to beak the red-hand count down, 5, 4, 3....The gentleman stops, and turns to the homeless woman. He then falls to his knees and says a short prayer; I cannot hear the words, I'm too far away. As he finishes, she looks up and smiles at him. He smiles back and crosses the street. This gentleman gave up an entire two signals to acknowledge this woman through prayer. Though I do not believe that prayer will be heard by any entity other than the person praying and those around them, this does not discount the power, and importance, of acknowledgement of something as wicked as homelessness. A challenge in which so many of us like to ignore or pretend is non-existence, or worse, pretend this challenge is not as harsh and hard as it is. Regardless of my views of the validity of religion, I cannot ignore the importance of it being an entity which can cause those that follow, truly follow, not just "Sunday believers," but those that acknowledge the importance that every prophet and god-son has preached, which is to care for those that suffer and those that struggle. This gentleman, through his beliefs, gave this woman a smile, and the knowledge that when she goes to bed at night, someone is thinking about her and cares about her well being enough to stop and give his God, which he truly devotes himself to, a mention of her. In the end, regardless of a beliefs validity, what I believe is most important is relieving the pain of those that suffer and always remember that there is always someone who hurts more than you and your acknowledgement is the thing that can save them, even for a brief second, relief from that pain. (Emphasis added)Caleb's words remind me of Thoreau's, and of Dennett's, and of Jesus's. Yeah, you read that right. Because all four of them are concerned with making sure that whatever we do, we act on what we believe, and that we act in a way that tries to make others' lives better.

I asked Caleb if I could share his words here. His reply is just as good as his original post. He said I could post his words, provided I include some links to local food shelves, soup kitchens, and homeless shelters. I love that.

So I will ask that if you share this post, you do the same thing by posting a link to at least one organization in *your* community that helps the homeless. In that way, let us make our prayers effective to the best of our ability, and may they rise to whatever heaven may be.

Here are my links for Sioux Falls, South Dakota. Please consider volunteering your time, giving your money, and remembering them and the people they serve in your prayers. And as you do so, may your prayers grow feet, and begin to change the world.

The Banquet

Union Gospel Mission

St Francis House

∞

College Athletics: Cui Bono?

This Strange Marriage of Athletics and Academics

This week I've been considering the place of sports on American university and college campuses. (See here and here for the other pieces I've written on this this week.)

If you grow up here, it doesn't seem at all strange, because it's simply how things are. But a little reflection suggests that the juxtaposition of academics and athletics is a little strange.

I say it is "a little" strange because throughout the ages thoughtful people have said that the two complement each other. Plato's Republic discusses the relationship between gymnastics for the body and philosophy for the mind, for instance. Of course, Plato, famous for his irony, is never wholly straightforward, and the target he is aiming at is probably something else, but the characters in his dialogue act as though bodily exercise and mental exercise are related.

Walking, Playing, and Thinking

One of Socrates' other students, Xenophon, wrote in his Cynegetica that the best education comes through learning to hunt, and that book-learning should only come after a boy has learned the art of coursing with hounds, and practiced it in the country. And there are many others who tell us that moving our bodies and learning go together: Maria Montessori reminds us that the work of children is play. Philosophers as diverse as Aristotle, Nietzsche, C.S. Lewis, Henry Thoreau and Charles S. Peirce tell us that walking and thinking are natural companions.

So the strangeness of the marriage of learning and playing is not the hypothesis that the body and the mind work both need exercise. The strangeness is the way we pursue - or, just as often, fail to pursue - that hypothesis. We are told that movement helps us think, and that playing team sports teaches us virtue. If all that is true, then why do we not encourage all students to play sports?

The Irony: We Do Not Practice As We Preach

Speaking of irony, consider this: What we claim and what we actually do are at odds with one another. We say sports are good for everyone, then we expect coaches to eliminate all but the best athletes from their instruction. Rather than advertising our schools as places where students can get an excellent physical education we expect our coaches to travel far and wide to recruit only the best athletes, i.e. those who need the least instruction and who are most likely to win competitions. It is fairly obvious that, rather than using athletics as a means of inculcating virtue and fostering better thinking, we use athletics to gain honor through victories.

And of course, this is obvious to us. We want to win games because winning is a form of advertising. For good or ill, we accept the fact that high school students will often choose our school in order to participate in the glory of competitions won. But we continue to give the other justifications for participation in athletics, perhaps because we perceive that it would be crass to come right out and say "Come to our college and bask in the glory won by others. It will thrill you, and it might help your job prospects," or "We hope that the victories of our athletes will help us to raise money from people who won't give unless we are winning games."

I don't want to be cynical about this. As I have suggested above and said directly in my previous posts, I'm in favor of athleticism. What troubles me about it is the way that certain college sports become increasingly professionalized. Why, after all, are student athletes considering unionizing? That's something employees do, not students.

Let Everyone Learn To Play

My conclusion is not to push for the elimination of college athletics, but for athletics to be brought more into line with the best reasons for preserving it. If playful exercise makes us better people and better students, then let's urge more students to play. Let's give less attention to inter-collegiate competition and more attention to teaching lifetime sports that will allow our alumni to enjoy the benefits of physical activity for the remainder of their lives. Let's teach poorer students to play golf so that when they enter the business world they aren't at a disadvantage when deals are made on the fairway. Let's teach everyone to swim. Let's take all our students on walks - serious walks, cross-country walks. Let's teach them what Thoreau calls the art of sauntering.

Playful activity takes many forms. We should resist the temptation to think of it as the pursuit of a ball. Swimming, hiking, rock climbing, Tai Chi, dance, yoga, and numerous other activities have the same moral and intellectual benefits as team sports. There should be as many opportunities for vigorous play as there are bodies.

Some of my friends have balked at this, understandably. Not all of us are athletic, or at least not all of us feel athletic. But I think a good deal of this is because many of us learned about athletics in a victory-oriented environment. That environment fosters a narrow and shallow view of the active human life. We may not all be quarterbacks, point guards, shortstops, or strikers, but all of us can be active within the limits of the bodies we have been given. If activity is good for us, then we should treat it as good for all of us. Play should not be limited to the activity of a few for the thrill of the inactive many. Play should be, as Peirce said, "a lively exercise of our powers," whatever those powers may be. And it should be a delight.

This week I've been considering the place of sports on American university and college campuses. (See here and here for the other pieces I've written on this this week.)

If you grow up here, it doesn't seem at all strange, because it's simply how things are. But a little reflection suggests that the juxtaposition of academics and athletics is a little strange.

I say it is "a little" strange because throughout the ages thoughtful people have said that the two complement each other. Plato's Republic discusses the relationship between gymnastics for the body and philosophy for the mind, for instance. Of course, Plato, famous for his irony, is never wholly straightforward, and the target he is aiming at is probably something else, but the characters in his dialogue act as though bodily exercise and mental exercise are related.

Walking, Playing, and Thinking

One of Socrates' other students, Xenophon, wrote in his Cynegetica that the best education comes through learning to hunt, and that book-learning should only come after a boy has learned the art of coursing with hounds, and practiced it in the country. And there are many others who tell us that moving our bodies and learning go together: Maria Montessori reminds us that the work of children is play. Philosophers as diverse as Aristotle, Nietzsche, C.S. Lewis, Henry Thoreau and Charles S. Peirce tell us that walking and thinking are natural companions.

So the strangeness of the marriage of learning and playing is not the hypothesis that the body and the mind work both need exercise. The strangeness is the way we pursue - or, just as often, fail to pursue - that hypothesis. We are told that movement helps us think, and that playing team sports teaches us virtue. If all that is true, then why do we not encourage all students to play sports?

The Irony: We Do Not Practice As We Preach

Speaking of irony, consider this: What we claim and what we actually do are at odds with one another. We say sports are good for everyone, then we expect coaches to eliminate all but the best athletes from their instruction. Rather than advertising our schools as places where students can get an excellent physical education we expect our coaches to travel far and wide to recruit only the best athletes, i.e. those who need the least instruction and who are most likely to win competitions. It is fairly obvious that, rather than using athletics as a means of inculcating virtue and fostering better thinking, we use athletics to gain honor through victories.

And of course, this is obvious to us. We want to win games because winning is a form of advertising. For good or ill, we accept the fact that high school students will often choose our school in order to participate in the glory of competitions won. But we continue to give the other justifications for participation in athletics, perhaps because we perceive that it would be crass to come right out and say "Come to our college and bask in the glory won by others. It will thrill you, and it might help your job prospects," or "We hope that the victories of our athletes will help us to raise money from people who won't give unless we are winning games."

I don't want to be cynical about this. As I have suggested above and said directly in my previous posts, I'm in favor of athleticism. What troubles me about it is the way that certain college sports become increasingly professionalized. Why, after all, are student athletes considering unionizing? That's something employees do, not students.

Let Everyone Learn To Play

My conclusion is not to push for the elimination of college athletics, but for athletics to be brought more into line with the best reasons for preserving it. If playful exercise makes us better people and better students, then let's urge more students to play. Let's give less attention to inter-collegiate competition and more attention to teaching lifetime sports that will allow our alumni to enjoy the benefits of physical activity for the remainder of their lives. Let's teach poorer students to play golf so that when they enter the business world they aren't at a disadvantage when deals are made on the fairway. Let's teach everyone to swim. Let's take all our students on walks - serious walks, cross-country walks. Let's teach them what Thoreau calls the art of sauntering.

Playful activity takes many forms. We should resist the temptation to think of it as the pursuit of a ball. Swimming, hiking, rock climbing, Tai Chi, dance, yoga, and numerous other activities have the same moral and intellectual benefits as team sports. There should be as many opportunities for vigorous play as there are bodies.

Some of my friends have balked at this, understandably. Not all of us are athletic, or at least not all of us feel athletic. But I think a good deal of this is because many of us learned about athletics in a victory-oriented environment. That environment fosters a narrow and shallow view of the active human life. We may not all be quarterbacks, point guards, shortstops, or strikers, but all of us can be active within the limits of the bodies we have been given. If activity is good for us, then we should treat it as good for all of us. Play should not be limited to the activity of a few for the thrill of the inactive many. Play should be, as Peirce said, "a lively exercise of our powers," whatever those powers may be. And it should be a delight.

∞

The Music of the Spheres: The Sun Is A Morning Star

Students in my Ancient and Medieval Philosophy class are required to spend at least four hours outdoors, gazing at the skies.

That may sound odd, but it arises from my conviction that philosophy needs labs. I call it my "Music of the Spheres" project, in which I invite them to consider what it would have been like to be Thales (who was one of the first to predict a solar eclipse), gazing at the night sky and thinking about the laws that seem to guide the motions of the celestial bodies.

The students are given specific instructions and they must come up with a clear research project that can be accomplished using only the tools available to ancient astronomers.

For me, the best part of the class comes at the end when I read their work, and I get to see their offhand comments, like this:

If you don't know what planets are visible right now; if you can't quickly identify a few constellations; or if you aren't sure what phase the moon is in, why not go outside and have a look? And why not share the moment with a friend?

The heavens are not yet done revealing themselves to us, and "the sun is but a morning star."

|

| The Morning Star, Good Earth State Park (SD), December 2013 |

That may sound odd, but it arises from my conviction that philosophy needs labs. I call it my "Music of the Spheres" project, in which I invite them to consider what it would have been like to be Thales (who was one of the first to predict a solar eclipse), gazing at the night sky and thinking about the laws that seem to guide the motions of the celestial bodies.

The students are given specific instructions and they must come up with a clear research project that can be accomplished using only the tools available to ancient astronomers.

For me, the best part of the class comes at the end when I read their work, and I get to see their offhand comments, like this:

"I saw the Milky Way and its Great Rift for the first time."My heart leapt when I read that one. This next one didn't make my heart leap, but it did make my heart glad, because it too is an important discovery:

"Stargazing is much more fun with a friend."We live beneath these skies but so rarely do we lie on our backs beneath them and gaze upwards. Rarely do we lift our eyes to the heavens to see what is there, and when we do, we are quick to turn away in boredom, as though it were a small thing to gaze into the greatest distances.

If you don't know what planets are visible right now; if you can't quickly identify a few constellations; or if you aren't sure what phase the moon is in, why not go outside and have a look? And why not share the moment with a friend?

The heavens are not yet done revealing themselves to us, and "the sun is but a morning star."

∞

I spent my twentieth year of life in Madrid, Spain, studying Spanish philology. Studying abroad is like laboratory work in a science class: the experience often teaches much more than lectures or readings could ever do. Many of the lessons are unanticipated, and depend on the interaction of student and environment.

One day in February, for no particular reason, I wanted to eat strawberries. A few blocks from my flat there was a market, so I walked there and searched for fruit stands. Finding one but seeing that they had no strawberries, I asked the proprietor, "Do you know where I can find strawberries?"

"Of course," he replied. "Right here."

"But you don't have any," I observed.

"Of course I don't," he said.

I was confused. "But you said I could find strawberries right here."

"You can," he replied. "But not until June."

This took a little while to sink in. I was accustomed to going to a supermarket at home in New York and buying any fruit I wanted at any time of year. Now I was being told what should have been perfectly clear: fruit is seasonal.

At first I was disappointed, but it took only a few minutes before I realized that this wasn't such a bad thing. It meant that the strawberries, when they arrived, would taste that much sweeter. The disappointment of having to wait would be repaid by the delight when they did arrive.

The experience didn't reform me, of course. I love eating my favorite foods year-round, despite not having harvested them and usually without knowing where they came from.

But it did make me appreciate some of the rhythms of life around me. The first part of Aldo Leopold's A Sand County Almanac, and most of Thoreau's Walden - two of my favorite books - follow the cycle of the seasons in the northern part of the United States. Their understanding of nature is one that allows nature to undergo its habitual changes. They might even say that what they know about nature arises from attention to just those changes. Phenology, the attention to when and how things appear and disappear throughout seasons, is one of the most important parts of learning to see the world. If I may speak an Emersonian word, phenology attunes us to the music nature wants us to hear. To speak less mystically, it accustoms us to natural patterns, and much of what the naturalist wants is to learn those patterns so well that we can then see when nature departs from them.

What are the calendars in your life? Technology has made many of them seem unnecessary, but I suspect that they give us much more than we know, just as my experience in Spain gave me unlooked-for lessons. We should be careful not to insist that others delight in the absences or disciplines we delight in; what may be a delightful, self-imposed fast to us may be devastating to someone who is genuinely hungry. When we choose them for ourselves, school calendars, planning one's garden, the liturgical calendars and holidays of the world's religions - each of them can offer us rhythms of both discipline and delight as we make ourselves wait for the strawberries to ripen, the hummingbirds to return, the exams to end, the candles to be lit.

Searching For Winter Strawberries

|

| A late October strawberry in my garden |

One day in February, for no particular reason, I wanted to eat strawberries. A few blocks from my flat there was a market, so I walked there and searched for fruit stands. Finding one but seeing that they had no strawberries, I asked the proprietor, "Do you know where I can find strawberries?"

"Of course," he replied. "Right here."

"But you don't have any," I observed.

"Of course I don't," he said.

I was confused. "But you said I could find strawberries right here."

"You can," he replied. "But not until June."

This took a little while to sink in. I was accustomed to going to a supermarket at home in New York and buying any fruit I wanted at any time of year. Now I was being told what should have been perfectly clear: fruit is seasonal.

At first I was disappointed, but it took only a few minutes before I realized that this wasn't such a bad thing. It meant that the strawberries, when they arrived, would taste that much sweeter. The disappointment of having to wait would be repaid by the delight when they did arrive.

The experience didn't reform me, of course. I love eating my favorite foods year-round, despite not having harvested them and usually without knowing where they came from.

But it did make me appreciate some of the rhythms of life around me. The first part of Aldo Leopold's A Sand County Almanac, and most of Thoreau's Walden - two of my favorite books - follow the cycle of the seasons in the northern part of the United States. Their understanding of nature is one that allows nature to undergo its habitual changes. They might even say that what they know about nature arises from attention to just those changes. Phenology, the attention to when and how things appear and disappear throughout seasons, is one of the most important parts of learning to see the world. If I may speak an Emersonian word, phenology attunes us to the music nature wants us to hear. To speak less mystically, it accustoms us to natural patterns, and much of what the naturalist wants is to learn those patterns so well that we can then see when nature departs from them.

What are the calendars in your life? Technology has made many of them seem unnecessary, but I suspect that they give us much more than we know, just as my experience in Spain gave me unlooked-for lessons. We should be careful not to insist that others delight in the absences or disciplines we delight in; what may be a delightful, self-imposed fast to us may be devastating to someone who is genuinely hungry. When we choose them for ourselves, school calendars, planning one's garden, the liturgical calendars and holidays of the world's religions - each of them can offer us rhythms of both discipline and delight as we make ourselves wait for the strawberries to ripen, the hummingbirds to return, the exams to end, the candles to be lit.

∞

Thoreau writes that not many people know the art of Walking. I am trying to learn it, and I think part of it involves learning to see what is there. My friend Scott Parsons has helped me to see better by teaching me to draw, since the pencil forces me to pay attention to what I actually see rather than just what I think I see.

Lately I have been trying to walk more - that is, to Walk more - in and around my city, Sioux Falls. I find, as I step off the sidewalks and walk a little more transgressively, the city is transformed. The habits of sidewalks and cars speed up the world around us until much of it vanishes in a blur.

Thoreau recommends trans-gressing, that is, stepping across paths and fences rather than letting them herd us to the destinations that habit and tradition and fetishized commerce want to lead us. Once he wrote that we should sometimes bend over and look at the world upside down. Sometimes this is all the "transgression" that is needed to overcome the aggressive habits that constrain us in daily life.

Another tool I have used lately is the camera, peering down its glassy pipe at single, simple things, trying to break up the landscape by gazing intently at just one point. Or, at times, using the lens to draw the world together, to see how much I can gather into its frame.

When I first moved to Sioux Falls almost ten years ago I thought it was a homely place, a city that did not care for design or good planning or beautiful architecture. Slowly, one frame at a time, I am changing my own mind. As I Walk through and around it, I am coming to see that it is, at times and in places, quite a lovely place to live.

Walking In Nature - In Sioux Falls

|

| Cardinal in Tuthill Park, Sioux Falls |

Lately I have been trying to walk more - that is, to Walk more - in and around my city, Sioux Falls. I find, as I step off the sidewalks and walk a little more transgressively, the city is transformed. The habits of sidewalks and cars speed up the world around us until much of it vanishes in a blur.

|

| Whitetail deer, east Sioux Falls |

Thoreau recommends trans-gressing, that is, stepping across paths and fences rather than letting them herd us to the destinations that habit and tradition and fetishized commerce want to lead us. Once he wrote that we should sometimes bend over and look at the world upside down. Sometimes this is all the "transgression" that is needed to overcome the aggressive habits that constrain us in daily life.

|