tradition

∞

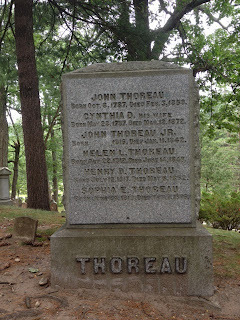

Thoreau: We Still Have Choices

“The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation….When we

consider what, to use the words of the catechism, is the true end of man, and

what are the true necessaries and means of life, it appears as if men had

deliberately chosen the common mode of living because they preferred it to any

other. Yet they honestly think there is no choice left. But alert and healthy natures remember that

the sun rose clear. It is never too late

to give up our prejudices.”

Henry David Thoreau, Walden. (New York: Modern Library, 2000) p. 8. (Boldface is my addition)

∞

Future Hopes, Present Experience, and the Wisdom of the Past

A reflection on Henry Bugbee's Inward Morning, his entry dated Friday, September 5.

Bugbee writes: "Of experience...we may hope for understanding in our own time, and in this we do not seem to have the edge on preceding generations of men."

Science grows from one generation to another. What we know is more advanced than what previous generations knew. But precisely because of this, we are alienated from what science will know, what it aims to know when it reaches its goal. Science uses experience, it swims in the medium of experience on a long-distance swim. We are like generations of migratory butterflies, none of us making the whole journey, but each of us making part of it so that the next generation may fly further. Standing on one another's shoulders we become the giants upon whose shoulders our intellectual descendants may stand.

At first blush, experience seems less worth knowing, since it is subjective, unquantifiable, subject to the winds of time and the diurnal tides of the chemistry of our blood. But experience is immediate. No generation is privileged; every generation receives the same share. Here our knowledge is not a deposit that we hope will gain interest for our children; it is something in our hands and for us now. The wisdom of the past does not advance the next generation so much as clarify our own.

Bugbee again: "It is not a question of our beginning from where they leave off and going on to supersede them. We are fortunate if we can become communicant in our own way with what they have to say."

Tradition has roots that mean handed-down. Bugbee reminds me, gives me words to articulate, why it is worth continuing to try to read ancient wisdom. He reminds me why, when I could have chosen to work in science, it is not a bad choice to work as a teacher, priest, curator, historian, poet, librarian - a custodian of the narratives of experience. Science aims forward beyond our lives; but experience is here now, where we live. Is it such a bad thing to live here and now?

Bugbee writes: "Of experience...we may hope for understanding in our own time, and in this we do not seem to have the edge on preceding generations of men."

Science grows from one generation to another. What we know is more advanced than what previous generations knew. But precisely because of this, we are alienated from what science will know, what it aims to know when it reaches its goal. Science uses experience, it swims in the medium of experience on a long-distance swim. We are like generations of migratory butterflies, none of us making the whole journey, but each of us making part of it so that the next generation may fly further. Standing on one another's shoulders we become the giants upon whose shoulders our intellectual descendants may stand.

At first blush, experience seems less worth knowing, since it is subjective, unquantifiable, subject to the winds of time and the diurnal tides of the chemistry of our blood. But experience is immediate. No generation is privileged; every generation receives the same share. Here our knowledge is not a deposit that we hope will gain interest for our children; it is something in our hands and for us now. The wisdom of the past does not advance the next generation so much as clarify our own.

Bugbee again: "It is not a question of our beginning from where they leave off and going on to supersede them. We are fortunate if we can become communicant in our own way with what they have to say."

Tradition has roots that mean handed-down. Bugbee reminds me, gives me words to articulate, why it is worth continuing to try to read ancient wisdom. He reminds me why, when I could have chosen to work in science, it is not a bad choice to work as a teacher, priest, curator, historian, poet, librarian - a custodian of the narratives of experience. Science aims forward beyond our lives; but experience is here now, where we live. Is it such a bad thing to live here and now?

∞

People Of The Waters That Are Never Still

Generations ago, one of my European grandfathers and one of my Native American grandmothers married, fusing in their offspring two peoples who had parted ways ages before, one heading west to the British Isles, the other to the Bering Strait and across to North America. I grew up in New York, near where they met and married, and my childhood is marked by memories of that land: tall oaks and white pines, deep forests, rocky crags over which the water pours, never still, always the same, always changing. The waterfalls of the Catskill Mountains are a constant presence in those mountains and in my memories. They are the waters of my mothers and fathers, and of my youth.

My family has since lost the languages those ancestors spoke, and this fusion of tribes has adopted the linguistic fusion of English. I have no intention of claiming a legal place among either of the nations from which I am descended, nor even to name them here. But I find that the memory of both, and of the lands they lived on, is rooted deeply in my consciousness of who I am. Last year, while visiting the British Museum, I saw a display of various Native American peoples, including my own. It was the only time a museum has moved me to tears. The words and ways of my forebears may be mostly gone, but they are not forgotten. My father taught me to remember them and what they knew of the land we lived on, and often, while teaching me to know the woods, he would remind me that those woods were old family acquaintances.

Jacob Wawatie and Stephanie Pyne, in their article "Tracking in Pursuit of Knowledge," cite Russell Barsh as saying that "what is 'traditional' about traditional knowledge is not its antiquity but the way in which it is acquired and used." Our word "tradition" comes from Latin roots that mean something like "giving over" or "handing down." Traditional knowledge is knowledge that is a gift from one generation to the next, a gift we give because we ourselves were given it. I am grateful to my father, in ways that I may never have told him - in ways that perhaps words cannot begin to tell - for the traditions he learned and loved and passed on to me. I'm grateful that he has not let me forget.

There is, of course danger in emphasizing one's heritage and one's roots, especially if we make that the source of a distinction between ourselves and others, or a way of diminishing the lives and traditions of others. Just as much as it matters to me that I am from the people of the waters of the Catskills, it matters to me that my ancestors shared those waters with one another, people from two continents recognizing, each in the other, the waters from which both arose.

For all that I have received, for the traditions like waters pouring over the cliffs, gifts like the Kaaterskill Creek, let me give thanks. Let me give thanks with my life, offering to those who come after me, a taste of the sweetness of those same waters.

(Photo: Kaaterskill Creek in New York State)

My family has since lost the languages those ancestors spoke, and this fusion of tribes has adopted the linguistic fusion of English. I have no intention of claiming a legal place among either of the nations from which I am descended, nor even to name them here. But I find that the memory of both, and of the lands they lived on, is rooted deeply in my consciousness of who I am. Last year, while visiting the British Museum, I saw a display of various Native American peoples, including my own. It was the only time a museum has moved me to tears. The words and ways of my forebears may be mostly gone, but they are not forgotten. My father taught me to remember them and what they knew of the land we lived on, and often, while teaching me to know the woods, he would remind me that those woods were old family acquaintances.

Jacob Wawatie and Stephanie Pyne, in their article "Tracking in Pursuit of Knowledge," cite Russell Barsh as saying that "what is 'traditional' about traditional knowledge is not its antiquity but the way in which it is acquired and used." Our word "tradition" comes from Latin roots that mean something like "giving over" or "handing down." Traditional knowledge is knowledge that is a gift from one generation to the next, a gift we give because we ourselves were given it. I am grateful to my father, in ways that I may never have told him - in ways that perhaps words cannot begin to tell - for the traditions he learned and loved and passed on to me. I'm grateful that he has not let me forget.

There is, of course danger in emphasizing one's heritage and one's roots, especially if we make that the source of a distinction between ourselves and others, or a way of diminishing the lives and traditions of others. Just as much as it matters to me that I am from the people of the waters of the Catskills, it matters to me that my ancestors shared those waters with one another, people from two continents recognizing, each in the other, the waters from which both arose.

For all that I have received, for the traditions like waters pouring over the cliffs, gifts like the Kaaterskill Creek, let me give thanks. Let me give thanks with my life, offering to those who come after me, a taste of the sweetness of those same waters.