trout

- Henry Bugbee, The Inward Morning. Don't try to read this book quickly, and if you're not prepared to do the hard work of thinking, move on and read something else. But if you're willing to read slowly and thoughtfully, this book can change your life. Bugbee was a philosophy professor and an angler.

- Henry David Thoreau, A Week On The Concord and Merrimack Rivers; The Maine Woods. Thoreau was an occasional angler, and an observer of anglers.

- Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac and the title essay in The River Of The Mother Of God, about unknown places. Leopold only writes a little about fish and fishing, but those occasional sentences about angling tend to be shot through with insight.

- John Muir, Nature Writings.

- John Steinbeck, Log From The Sea of Cortez. An apology for curiosity, in narrative form. One of my favorite books.

- Paul Errington, The Red Gods Call. Not brilliant writing, but a fascinating set of memoirs from a professor of biology who put himself through college as a trapper, and about how the Big Sioux River in South Dakota was his first real schoolroom. He talks a good deal about hunting and fishing and what he learned through encounters with animals.

- Kathleen Dean Moore, The Pine Island Paradox. Moore is an environmental philosopher who writes winsomely ans insightfully about what nature has meant to her family.

- Nick Lyons. Nick very kindly wrote the foreword to my book, and when I first got in touch with him about this I discovered he and I had lived only a few miles from each other in the Catskill Mountains for years. Sadly, by the time I discovered this I'd already moved away, and he was packing up to move to a new home, too. We both love the miles of small trout streams of those mountains, though. Nick has been a prolific writer and he has promoted a lot of great writing through his lifelong work as a publisher as well. Nick has a new book, Fishing Stories, just published in 2014.

- Norman Maclean, A River Runs Through It

- Ernest Hemingway, especially "Big Two-Hearted River" and the other Nick Adams stories

- James Prosek. Several books, including Trout: An Illustrated History; Early Love And Brook Trout; and Joe And Me: An Education In Fishing And Friendship

- Ted Leeson, The Habit Of Rivers

- Kurt Fausch’s new book, For The Love Of Rivers: A Scientist’s Journey. Brilliant writing by one of the world's leading trout biologists.

- Craig Nova, Brook Trout and the Writing Life. I also like his novels, and will recommend The Constant Heart.

- Christopher Camuto, who writes frequently for Trout Unlimited's journal, Trout.

- Ian Frazier, The Fish's Eye.

- Douglas Thompson, The Quest For The Golden Trout

- Izaak Walton, The Compleat Angler

- Dame Juliana Berners, The Boke Of St Albans, later editions of which contain A Treatyse of Fysshynge with an Angle, possibly authored by someone else.

- Nick Karas, Brook Trout (a nice collection of short works about brook trout, including some of my favorite stories)

- Lee Wulff

- Lefty Kreh

- John Gierach. Gierach has written a lot about angling, so it's not surprising that so many people mention him to me. Many of those mentions are positive, but some anglers mention his name with disgust. I haven't read much of his work, so I can't yet say why.

- David James Duncan, The River Why. This is a fun novel set in the Northwest, but it reminds me of the New Haven River in Vermont: there are some long dry stretches one has to plod through, but repeatedly one comes to depths that make the flatter, shallower parts worthwhile.

- Thomas McGuane, The Longest Silence.

- Bill McMillan

- Roderick Haig-Brown

- Mike Valla, The Founding Flies

- Michael Patrick O’Farrell, A Passion For Trout: The Flies And The Methods

- Peter Reilly, Lakes and Rivers of Ireland

- Derek Grzelewski, The Trout Diaries: A Year of Fly-fishing In New Zealand and The Trout Bohemia: Fly-Fishing Travels In New Zealand

- Eeva-Kaarina Aronen, Die Lachsfischerin. A novel set in Finland, about fly-fishing and fly-tying in the 18th century. The title translates as “The Salmon Fisherwoman”

- Ian Colin James, Fumbling With A Fly Rod (Scotland)

- Zane Grey, Tales of the Angler’s Eldorado: New Zealand

- Leslie Leyland Fields, Surviving the Island of Grace; and Hooked! Fields and her family are commercial fishers in Alaska, and her writing comes recommended to me from a number of sources.

- Sheridan Anderson, The Curtis Creek Manifesto

- Harry Middleton, The Earth Is Enough: Growing Up In A World Of Fly-fishing, Trout, And Old Men (Memoir)

- Paul Schullery, Royal Coachman: The Lore And Legends of Fly-fishing

- Gordon MacQuarrie

- Patrick McManus

- Vince Marinaro, The Game of Nods

- Rich Tosches, Zipping My Fly

- Robert Lee, Guiding Elliott

- Peter Heller, The Dog Stars (novel)

- Paul Quinnett, Pavlov’s Trout

- Dana S. Lamb Where The Pools Are Bright And Deep; Bright Salmon and Brown Trout

- John Shewey, Mastering The Spring Creeks

- Ernest Schweibert, Death of a Riverkeeper; A River For Christmas

- Richard Louv, Fly-fishing for Sharks: An Angler’s Journey Across America

- John Voelker’s short story “Murder”

- Dave Ames, A Good Life Wasted, Or 20 Years As A Fishing Guide

- Craig Childs, The Animal Dialogues, especially the chapter “Rainbow Trout”

- Randy Nelson, Poachers, Polluters, and Politics: A Fishery Officer’s Career

- Anders Halverson, An Entirely Synthetic Fish: How Rainbow Trout Beguiled America And Overran The World

- Thomas McGuane, A Life In Fishing

- Bob White

- Robert Ruark

- Tom Meade

- Hank Patterson

Catch Your Breath: A Winter Meditation on Trout - My latest article, in Hothouse

My latest publication, a winter meditation on the beauty of brook trout, in Hothouse // Solutions. This is my first publication in collaboration with my son, Michael O'Hara, my favorite pro photographer.

A little taste of my article:

The trout is, for me, an icon of what I hasten to ignore.

I hope you enjoy this short read. Consider subscribing to Hothouse.

We can all use good news, after all. I like the short format and the focus on solutions, not just on problems.

Of course, if you like what I've written here, you might also like my book on brook trout.

My Father's Stories

Dear Dad,

We recently had a conversation about what kind of wisdom comes with age. We’ve both known some old people who seem unwise, and some young ones who are ahead of the game. And I think you and I (both of us now being over the trusted age of thirty) have occasionally been unwise in our post-adolescent days. Oh, well.

While I’ve known a few foolish geezers, over the years my respect for a certain kind of wisdom I see in you has continued to grow: your stories. Again and again when I have faced uncertainties in my life, I have returned to your stories.

Your stories aren’t doctrines, because that’s not what stories are. So I’m not saying they’re right or wrong. What matters is that they’re yours, and when you tell stories about your own life, they’re some of the truest stories I can imagine. You only mess them up when you try to explain them. That’s best left for Aesop. Your stories are more like compressed data. They do more work than any quantum computer I’ve heard of can do, and they are like a vein of gold that keeps growing and branching the more I dig into it. They explain themselves, and they are resilient.

Some of your stories are entertaining. My kids have heard stories of your experience in the National Guard so many times they probably not only think that I was there with you in that tank, they probably can imagine themselves in there, firing at trees hundreds of yards away in target practice.

But your stories do much more than entertain. They teach. When I think of you riding in the back seat of the car while your parents heard the news of the bombing of Pearl Harbor and you wouldn’t shut up, I feel like I am present there, and I feel like I am learning about my family, and what it means to be a family. You’ve never told me what Gram did when you were making too much noise, but that doesn’t stop me from remembering what I know of her, and imagining her response. And you haven’t mentioned your brother in that story either, but I can imagine him learning a lesson as well when Gramps turned around and smacked you to get you to shut up while he contemplated what was about to become of his military service, and of his wife and sons, and his widowed mother and his younger siblings. Just reflecting on that makes me think more seriously about my own obligations to others. It’s a tightly-packed story that is full of webs of relationships, and I am grateful for every time you’ve told me.

The same goes for all the stories you’ve told me about your life during the war, and afterwards. The way Gramps prepared you all for the trip back home while he prepared himself and his men for war. The way Uncle Charlie taught you to use the tools he knew. You’ve told me about Uncle Charlie so many times I wish I knew him myself. In fact, I think I do, through you.

Because, after all, your stories are also like tools. I think about the stories you’ve told me about how to take an engine apart so that you can put it back together again. I remembered that when I took apart my lawn mower engine once, and I thought about it the other day when I took apart the vacuum cleaner to figure out why it wasn’t working. I took out the parts methodically, and laid them out in order of removal, so that I could put them together again. You taught me about algorithms when I was a kid, sketching some out on napkins at the pizzeria in Woodstock, but also teaching me the word “algorithm” and then telling me stories that illustrated algorithms. You were making me a philosophy professor whether you knew it or not. Not bad for an electrical engineer!

A few years ago my youngest brought his friend over to our

house. Her car door wasn’t working right. He told her to park it in the

driveway and said that his dad could fix it. Somehow he knew that I wasn’t

afraid to take things apart and tinker with them. He also knows that I still

own and use tools you gave me when I was a boy. As we took apart that car door

there in our driveway, Matt watched and learned. Not long afterwards, when he

wanted to fix something on his own car—something he had never done before—he asked

to borrow my tools, and got to work. He was unafraid to use tools, and unafraid

to try something new. You know why? Because he saw it in me. And you know what

he saw in me? He saw you. Your stories—the ones you told and the ones you

showed me—those live in me all the time. Not surprisingly, he's now certified as an automotive electrician, and working as an auto mechanic. And he's good at his job. That's a picture of your stories, living in your grandson. I hope you're as proud of him as I am.

I think one of the things I have learned from your stories is a willingness to try to work with my hands to make good things. I’ve made a lot of the furniture in our house, and as you know, I’ve worked with stone and bricks and mortar on three different continents now. When I lay stone, I am always thinking about the structure in front of me, thinking about stresses and balance, physics and aesthetics. Despite a lack of formal training in engineering, standing beside you while you built a pier on the reservoir, or while you explained the bridge you built across the creek behind your house, gave me both the gumption to try building things myself, and a sense of what would work and what wouldn’t. Of course, that bridge also came with a lesson in law (which is why you couldn’t modify the banks) and a lesson in measuring the rate of flow of a river (something I had no idea how to do until you told me that day.) I can’t look at bridges and cantilevered and suspended structures without thinking of the engineering lessons you taught me through your stories.

The same is true for my adeptness with languages, and for my ability with music. Yeah, some of that is probably genetic (from you, again) but a lot of it is just learned fearlessness. I have never seen you turn away from a musical instrument just because you hadn’t yet received lessons in it. And I’ve seen you play in public many times, and your stories—I want to emphasize this—your stories of messing up have been a huge gift. “Don’t stop, just keep playing!” This is one of the things I tell my students now about public speaking, and about writing essays. “Always have a song you’re ready to play.” Years ago when I was having dinner at the home of the Lutheran Bishop of Nicaragua, someone handed me a guitar and said “Play us a song.” This was a complete surprise to me, but thanks to your stories, I was ready, and I led the whole group in several songs.

If I tried to write down all the stories you’ve told me, it would take a long time. I hope you continue to write down the stories you know. And I hope you tell them simply, unadorned, without feeling like they need to be dressed up. Just pick up that guitar and sing them, Dad. You have such a good voice, such a gift for music. You’re our family’s Homer, our Vergil.

In the same vein, if I tried to write down all the ways you show up in my classes, or in the ways I raised my kids, I doubt I’d be able to get it all down, but I hope this little letter at least gives you an idea of that. Those napkins you scribbled on at the pizzeria helped my kids do better in math and science. The times you told me about meeting someone who spoke another language and you tried speaking to them have indirectly emboldened your grandkids to study and work abroad in Asia, Africa, Latin America, and Europe. You taught me my first lessons in logic, and I taught them to my kids, and then your granddaughter grew up to be a far better reasoner than either one of us. Hopefully you and I will get a little credit for that when her biography is written—a little, but not too much. She deserves most of the credit for taking the stories we passed on, unpacking them, and then retelling them in her own way. And I love to watch her do that.

Speaking of languages, your stories have taught me in some other ways, too. Well before I could read Chomsky you mentioned him to me. I don’t remember what you said, but I remember the way you said it. It was like when you mentioned Feynman, Bernoulli, Les Paul, Vivaldi, Buckminster Fuller, Linus Pauling, or one of the other creative thinkers you were the first person to teach me about. Years later, when I was teaching at Penn State, one of my students mentioned Chomsky, and said wistfully that she wished she could have the chance to meet him. I asked her “Have you tried writing to him or giving him a call?” “I can do that?” “Why not?” I was passing along to her some of your willingness to try. After she went home to Boston for semester break she came to visit me in my office, and told me that she had called him and he invited her over to his campus. They talked for an hour over coffee. She was thrilled! That’s a win in your column, Dad. Well done.

When I was a boy you also bought me a subscription to Scientific American, and a copy of Van Nostrand’s Scientific Encyclopedia. I wish I still had that Van Nostrand’s. It’s horribly out of date, but I spent many hours paging through it, and it was a gift of love. People don’t often think of science as stories, but what else are scientific papers? They’re letters written to strangers, telling stories as clearly and as straightforwardly as they can. I remember reading about the work of Benoit Mandelbrot in Scientific American, and I have not stopped learning from that story ever since. If I had a list of how many times I’ve taught principles I learned from those articles, it would be a very long list. Another win in your column, I think.

I could go on for a long time, but I have more work to do today, so I’ll end here. I just wanted to say, in the form of a letter about stories, that I love you. Thanks for telling your stories, Dad. I keep telling them all the time.

With love,

Dave

*******

I write about my father in several places, including in my book Downstream. If you want to see some more of what I've written about him on this blog, click the "my Dad" link, below.

Butterflies In My Stomach

|

| Kentucky roadside butterfly banquet. Can you see the little one? |

Here is the danger of becoming a professor of Environmental Humanities: people begin to assume that you care about nature, and that you are willing to share what you know.

Both of these things are true, by the way. (Many of my photos of wildlife and nature are here, on my Instagram account. I do care, and I am delighted to share the little I know.)

Over the years, I have come to love insects. This has come about partly through my years studying trout, char, and salmon, and of the places they live. I've spent a good portion of the last decade walking Appalachian waterways from Maine to Georgia. Over that same time, I've walked hundreds of miles through the remaining forests of northern Guatemala and Nicaragua. As both a researcher and teacher I've walked through the mountains of the American West; and I've made similar excursions to the foothills of the Brooks Range, the Kenai Peninsula, and Lake Clark National Park in Alaska.

The fish that I love depend upon the insects, so, like so many people who gaze at salmonids, I have come to know many riparian insects.

Once you study the insects along the streams, you start to notice the other plants and animals that depend upon them, too. In Kentucky I have come upon a steaming pile of bear scat that was full of half-digested cicadas. I've started to notice the wings of insects, left behind by the birds that only eat the fleshy bodies of the bugs they catch.

|

| Butterfly wing, left behind by birds. Guatemala. |

From there, it's not a big leap to realize that if the fish and the birds and the plants need the insects, then so do I. Butterflies and other insects feed the larger animals my species eats, and they pollinate the plants that feed us. All of us have the actions of butterflies in our stomachs. Can you see the lepidoptera in this next photo? There are quite a few of them, resting on the bark of this tree in Petén.

|

| Gray cracker butterflies, Petén, Guatemala. |

Little six-legged creatures feed us all. The small things matter.

And so do my students, even if they're not currently enrolled in one of my classes.

So in the past week I’ve gathered a few hundred of my best butterfly photos to share with my student. This photo is one of the worst in photo quality, but it’s a great image nevertheless:

|

| Butterflies on the ground in Kentucky, 2008. |

I took this nine years ago in the mountains in Kentucky while working on my book on brook trout. Three distinct species of butterflies are gathered here, sipping minerals from the ground. My coauthor Matthew Dickerson and I came upon this arboreal banquet by chance.

I wish I'd had a better camera with me. For now, the blurry image is enough to bring to mind that memory of hundreds of lepidoptera sipping and supping together on the forest floor, filling their bellies with the bare earth before flying off to pollinate flowers that, through a complex net of relationships, would someday fill my belly too.

A Pretty Good Year

As my regular readers know, I'm a professor of philosophy and classics, and I teach a wide range of classes. (You can click on the "Teaching" link above to see a sampling of the courses I teach.)

Often people assume that means I wear tweed and a bowtie and that I spend my time in classrooms talking about old books. All that is true, but it's only a part of what I do.

In fact, most of my favorite classrooms are outdoors, where I'm likely to be found wearing jeans and hiking boots, a parka, or a wetsuit and snorkel.

Over the last dozen years or so my teaching and research have tended towards the environmental humanities. Think of this as the merging of the humanities side of the liberal arts with a close observation of the natural world. I consider my work to be a continuation of the work that Thales and Aristotle did when they paid close attention to animals on the ground and to the skies above, and of the work of Peirce, Thoreau, and Bugbee, all of whom let a rising trout or a solar eclipse provoke philosophical reflection.

While I don't work in an indoor laboratory, I think that education is not about the imparting of information or the filling of an empty vessel with ideas. Education is the kindling of a fire, as Plutarch wrote. And that fire is kindled by the kinds of experiences that we get in labs, art studios, shared meals, liturgies, study travel, and seminars. Lecture halls are a fine place to discuss environmental policy, to be sure. But so is a prairie, especially when you're waiting for water to boil on your camp stove, and watching the sun's beams break over the horizon and melt a light frost on your tent.

When I'm at home, I like to take my classes outside to sit under trees on campus. In the fall, I try to bring my Ancient Philosophy students camping in the Badlands of South Dakota where we can view the stars far from urban glow. Most Januaries, my students and I are in the subtropical forests of Guatemala and on a barrier island in Belize, studying ecology and culture. I rarely take a spring break, since I usually take that week to teach a course in Greece. Last summer I started teaching a class on trout and salmon in Alaska.

Those are all beautiful, memorable places, but I don't visit them as a tourist. I go to these places because I want my students to understand what is at stake when we talk about environmental regulations and practices. I want them to meet displaced people whose permafrost islands are melting or whose forests are being burned down for meager cropland. I want them to see the disappearing mangroves so that they can consider the full cost of seafood. When they stay in homes in Guatemala, my students will meet people who can never again be a mere abstraction; after we return, my students will know that the people struggling to cross borders are not nameless, faceless strangers, but people who are looking for ways to feed those they love.

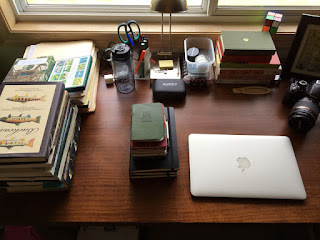

A little less than a year ago I was finishing up a year that had brought me to all these places. I taught in the South Dakota Badlands, in Central America, in Greece, and in Alaska. Along the way, I had begun studying environmental law at Vermont Law School as a way of enhancing my teaching and my research. It was a good year, and as August was winding down, my desk was covered with field notebooks full of observations from Alaska and Guatemala, ready to be written up. My field notes are usually accompanied by thousands of photographs, and hundreds of sketches. I began the fall semester last year ready to teach, and ready to write.

|

| Field notes. A picture of some of the work I do when I'm inside, and not teaching; or, if you like, a picture of my desk as I recover from my injuries. I have a lot of catching up to do. |

And then I wound up in the hospital with some serious injuries. Those injuries put a sudden stop to all my teaching last fall, and for a long time I lost most of my ability to write. (I'll try to write more about the injuries and my subsequent disabilities later; it's not an easy thing to write about yet.)

Now, as this summer hastens towards the beginning of another school year, I am able to look back on last year with a sense of good fortune - albeit mixed with one very bad day and its long-term consequences. Physically, I'm regaining my flexibility and strength, a little at a time. I'm not where I was a year ago, and I may never be there again, but I'm alive and able to walk, so I'll count that in the "win" column of my life's scorecard. Intellectually, most people seem to think I'm doing fine, so I'll also count that as a win. Although it left me exhausted each day, I was able to teach again this spring, and I plan to be back in my classrooms (Deo volente!) this fall.

But here are these field notebooks, and hundreds of unedited pages on my hard drive. It was my habit to write daily. Over the last year, recovering from a brain injury has made it hard to write more than a few sentences at a time.

This morning I was looking at some of my pictures from my research in the Arctic last summer, and I was hit with a feeling of loss. Those photos and those notes should be a book by now, and perhaps several articles and book chapters, too. Instead, over the last year, as I have waited for my body and brain to heal, and as I struggled to do my teaching, I had no strength to write.

It feels funny to say that, but perhaps I am not alone in finding that a brain injury can be slow to heal and extremely tiring. I don't say that to get your sympathy. I am blessed with a very supportive community and an amazing wife who somehow has kept our life together and nursed me through my healing process. I'm fortunate. But if you've read this far, you might consider whether there are others around you who look like they're doing well physically but who might be nursing invisible wounds or who might be struggling to cope with invisible disabilities. This past year has given me a new perspective on that by making me aware of my own disabilities, most of which you won't notice if you see me at the gym or in one of my classrooms.

I might not be able to write another book yet, so for now, here's my plan: I'll write a little at a time. Thankfully, I've got my notes, sketches, and photos. I'll start with them.

If you're curious about how a professor of philosophy and classics does research and writing about nature - and how he works to recover from a serious brain injury - you might check out some of my recent publications. My book Downstream is the result of eight years of field research on the ecology of the Appalachians, with a focus on brook trout. On this blog you'll also find my recently published poem, "Sage Creek," which might give you a glimpse of my ancient philosophy class camping and stargazing in the Badlands. Or feel free to look at my photos on Instagram. Even when I can't teach in the field, I can still wander my garden with a hand lens and camera.

Professors of Trout

Really, this shouldn't be too surprising. Fly-fishing requires us to look attentively, seeing past the surface of the water in order to discern what is happening deeper down. Far more than simply catching fish, fly-fishing is a practice of reading water as though it were a natural text.

Several authors, professors, and fellow-thinkers have been helping me to deepen my literacy in these streams of thought lately. Among them are Kurt Fausch, Douglas Thompson, and David Suchoff.

Fausch is one of the world's authorities on trout biology and ecology. I had the privilege of reading a draft of Fausch's forthcoming book, For The Love Of Rivers, (see the book trailer here) and I highly recommend it. It is a lovely marriage of science and lyrical writing. You'll learn a lot about the life of rivers, written by a remarkable writer who loves them deeply.

Thompson's book, The Quest For The Golden Trout is next on my to-read list, but I've already snuck some glimpses at it and I am eager to get to it. I'll post more about it when I'm done. Meanwhile, check out his webpage.

I discovered Suchoff recently when I saw one of his students fly-fishing for bonefish in Belize. I teach a January-term field ecology course for Augustana College in Guatemala and Belize. One morning I looked out over the intertidal flat and saw a young woman casting a heavy fly in turtle grass on South Water Caye. I ran into her later on shore and she told me about a terrific class Suchoff teaches at Colby College in Maine. He teaches them the literature of fly-fishing, arranges professional instruction, then takes his students fishing in California, and teaches them to write about it. You can find him on Twitter, too.

One of the joys of research is that it gives me the excuse to write to strangers who share my interests and ask them to teach me what they know. My acquaintance with two of these professors is quite new, but already I've learned from them. The third, Fausch, I've known for long enough that he reviewed a draft of my book and kindly pointed out a few errors before I made them permanent in print.

These are, as I've said, just a few of the university professors who study trout. Are you another? I'd love to hear from you if so.

Recommended Reading: Fly-Fishing and Trout

|

The focus of the course will be the char species of Alaska. These species, all members of the genus salvelinus, are commonly thought of as trout. Brook trout and lake trout are both char, as are Dolly Vardens and arctic char.

These are beautiful fish. I think many anglers love them simply because they are so beautiful to look at. When I pull one from the water I am immediately torn between wanting to hold this precious thing closely and the urge to release it immediately, before my coarse hands pollute its loveliness. The name "char" might come from Celtic roots, like the Gaelic cear, meaning "blood." They are more multi-hued than rainbow trout. The red on their sides and fins catches the eye and holds the gaze.

Over the years I spent researching and writing my own book on brook trout, I did a lot of reading. Some books call me back again and again, like Henry Bugbee's The Inward Morning and Steinbeck's Log From The Sea of Cortez. Neither one is chiefly about fly-fishing or about trout, but they're both written in a way that makes me re-think how I view the world. And they do both talk a good deal about fish, and fishing.

|

| Mayfly on my reel. Summer 2014, Maine. |

If the point of writing books about fish is to give techniques, or data, then we don't need many at all. But stories about fish and fishing are rarely about the taking of fish. More often they are about the states of mind that open up as we prepare to enter the water, or as we stand there in the river. Fishing is to such states of consciousness what kneeling is to prayer; the posture is perhaps not essential, but it is a bodily gesture that does something to prepare us to be open to a certain kind of experience. I won't belabor this point. Read my book if you really want me to go on about fishing and philosophy. For now, let me present some of my recommendations, plus the recommendations I've received:

On Nature

I teach environmental philosophy and ecology, so I begin with some orienting books.

Some Favorites

Classics

These have been recommended time and again. I'm not sure many people ever actually read the first two, though they become prized volumes in the libraries of anglers around the world.

Most Recommended

Fly-Tying

Places

One reason why there is so much writing about fishing is that fishers tend to be students of particular places. Yes, some people fish by indiscriminately approaching water and drowning hooked worms therein, but experience tends to cure most young anglers of that method. Fishing puts us into contact with what we cannot see (or cannot see well) under the water; experienced anglers learn to read the signs above the water and the place itself. We return to the same place as we return to beloved passages in books or to favorite songs, to know them better through repetition.

Other Frequent Recommendations

If I talk to a group of anglers about books for long enough, one or more of these will eventually be mentioned. Stylistically and in terms of content, they're quite different, but they all seem to speak to important moods and thoughts of anglers.

Other Recommendations

Most of these I don't know at all, so I'm not recommending them, just mentioning them. Of course, if you have more recommendations (or corrections), please feel free to add them to the comments section, below.

I'll conclude with a few other recommendations. First, when I've asked for recommendations about texts, a handful of people tell me "Tenkara." This isn't a text, but a kind of rod, and a method of fly-fishing. And yet people continue to say that word to me when I ask for texts. Why is that? I have a few guesses: there isn't a lot written about tenkara, but people who practice it have come to love its simplicity and grace. I'm not a tenkara fisher (yet) but I'm eager to learn. I have a feeling that tenkara, like so many spiritual practices or like some martial arts, is something that makes people feel they way great writing makes us feel: in it we transcend the immediacy of our environment.

Along those lines, one commenter on Facebook said this to me about my students: "Give them [a] fly rod and a stream and let them write [their] own story." There is wisdom here. It is one thing to read about waters, and quite another to enter the waters on one's own feet. Even so, I think it's important and wise to learn from those who've gone before us, too.

If you're interested in seeing some of my other book recommendations, have a look at this, this, and this.

Why Does A Philosophy Professor Write About Trout?

To this question I have three brief replies, which I'll say more about later.

The first is that this book really is about those things, even if it won't appear to be so at first blush.

The second is that in fact, I think more philosophers should turn our attention to the matter of lived experience, to our technology, to our tools, and to our ways of knowing the world. It's not enough to know things about the world; we ought to ask just how we know the things we know, and how our tools and our very modes of life and habits affect that knowledge. And everything that hangs on that knowledge.

And for my third brief reply, I turn to Edward Mooney, who, in his introduction to Henry Bugbee's beautiful book, The Inward Morning, recalls a question Martin Heidegger asked Bugbee in August of 1955: “What occasion prompts philosophical reflection?”

Mooney writes that no doubt Heidegger “anticipated a flat American response. Yet he found his question returned in a Socratic reversal. Bugbee simply asked, echoing a Basho haiku, 'Could the sound of a fish leaping at a fly at dawn suffice?'”

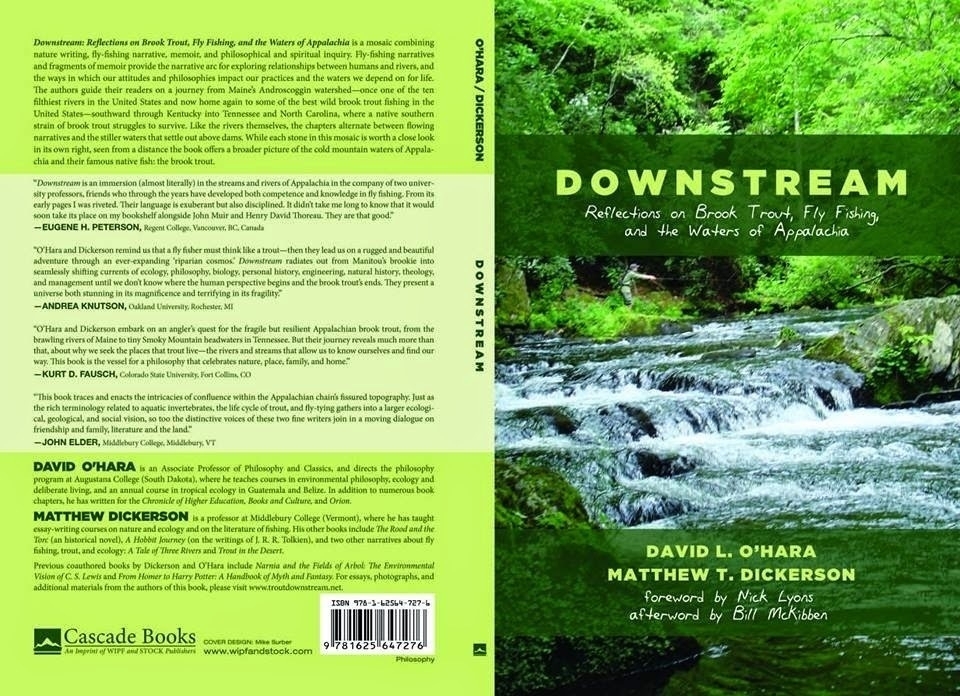

Downstream: My New Book On Brook Trout and Appalachian Ecology

It is now listed on Amazon as well, though not yet in stock there.

I'm very grateful for the foreword by Nick Lyons, the afterword by Bill McKibben, and the kind words offered by such a wide range of brilliant scholars of theology, literature, and science, like Eugene Peterson, Andrea Knutson, Kurt Fausch, and John Elder.

Green Mountain Creek

Matt and I stand thigh-deep in one of the small streams that

tumble down the eastern slopes of the Green Mountains. Many of those

streams, including this one, have carved steep gorges over the

millennia. As the water falls it strips away the sand and loam, leaving

a course choked with jumbled boulders.

Matt and I stand thigh-deep in one of the small streams that

tumble down the eastern slopes of the Green Mountains. Many of those

streams, including this one, have carved steep gorges over the

millennia. As the water falls it strips away the sand and loam, leaving

a course choked with jumbled boulders.Every year a few more trees, undercut by the current, tip over into the stream, where they lodge against the boulders and form temporary dams. As the water flows over those dams it digs deep plunge pools, bubbling and swirling for a few feet, then quickly settling into swift, clear, tea-colored glassy pools. The water slows only long enough to catch its breath before it plunges again, stair-stepping down the mountain, moving the mountain itself downstream one grain of sand at a time.

Beside us, logs carpeted in moss play host to uncounted lives of plants and animals. Trees reach their branches down into the cleft cut by the river, searching for sunlight wherever they can in this steep gorge. Small flies whirl restlessly across our vision. Their blue wings and olive bodies seem an unnecessary and extravagant dash of color on something so small, so ephemeral.

Vermont is named for the greenness of its mountains, or les monts verts as the first French settlers called these ancient hills. One of the rivers nearby is called the Lemon Fair, its name preserving the French sounds in misplaced English words. A sweeping glance would call this place green, but it only takes a moment of slowing down to really look before you see all the rainbow represented here.

Much of the color is underwater, on the scales of the fine-featured trout that fin the current before us. The native brook trout are dappled a vermiculated green above, fading to pale bellies below. Their fins are slashed with bright red and white. The rainbow trout, imported from the west coast, iridesce when a beam of sunlight finds its way down through the leaves and the water. The young brown trout - far from their native Europe - shine like salmon. Under the rocks small tan sculpin harvest tiny invertebrate meals.

Gray stones slide slower than glaciers down the bank, moving imperceptibly and irresistibly toward the sea. On the bank, seven tiny mushrooms stand up, no taller than my thumb, their caps bright orange like yearling efts.

It is a perfect day. We are grateful to receive it, grateful to be here, to stand in these waters as their life flows around us.

*****

|

| My friends Bill and Brian paddle the Concord River, as Thoreau once did. |

“[F]ishers can be natural historians and waterside contemplatives par excellence."

Anecdotally, I find that hunting and fishing have made me less of a carnivore, and increasingly concerned with animal flourishing. (The quote from Stephanie Mills is found in Epicurean Simplicity, published in Washington, Covelo, and London: Island Press/Shearwater Books, 2002 p.125.)

*****

Hunting, Fishing, and Climate Change

|

| Trout angling in the Black Hills of South Dakota |

This article in Outside makes just this case, with the additional point that we who seek our food in the wild are the people who ought to be advocating for real conservation: not just changes to game laws, but changes in the way we live in relationship to our world.

Do Philosophy Classes Have "Labs"?

When I was preparing to go to grad school I was torn between two choices: Ph.D. in marine/riparian biology, or Ph.D. in philosophy? I love fish, aquatic invertebrates,

(well, most of them, anyway) and the environments they live in. Wouldn't it be great to make freestone streams and tidal pools into my classrooms?

But I also love philosophy. Philosophy has connections to every other discipline; it offers a unique perspective on human activities; and it promotes some of the most interesting and fruitful conversations I know of. (Yes, I admit some professional bias here, and don't begrudge others a similar bias towards what they love.) Philosophy classes take on questions about truth, value, meaning, religion, justice, science, language, reason, history, relationships, and much more. It can be very difficult, but there's usually a huge payoff for the effort you put into it.

Now that I teach philosophy, I often find myself lurking around the biology department at my school, to read their journals, to talk with the professors there (who patiently put up with my presence there), and to eye their labs with envy.

Now, I think bio labs are great places, but it's not the places themselves that I most like. It's rather the idea of the place. Labs are spaces set apart for learning by experience. We have labs for the sciences, and we have labs for the arts as well (though we usually call those "studios"). In the social sciences they use labs for observing human activities, and foreign languages have (or ought to have) labs for practicing language. Writers have workshops, historians have museums and archives, and other disciplines have internships.

Philosophy, unlike all these other disciplines, does not appear to have any labs at all. At least, not at first glance.

Partly this is due to the reflective nature of philosophy: philosophers have often understood our discipline as a step back from experience in order to gain a cool, disinterested view of the world. To some degree, we still think that, but that idea of having a privileged access to reality through the use of the right kind of language, or through a scientific worldview, has fallen under suspicion. Pace Descartes, we don't necessarily understand the world better by turning completely away from it.

Contrary to popular opinion, "philosophy" is not a synonym for "opinion." Nor is it a synonym for "doctrines." Philosophy has grown and changed quite a lot in the last few centuries, which means that is not always easy to define. One thing that is common to all philosophers, however, is that philosophy is an activity. Doing philosophy is not the mere rehearsal of past views, nor is it merely an attempt to present our already established opinions in clearer or more persuasive language.

Philosophers do, in fact, set aside spaces and times for practicing philosophy. One important kind of lab philosophers have is the seminar, which has its roots in Plato's practice of philosophy. Whatever else we might say about Plato, he knew how important good conversation is to advancing philosophy. In his dialogues, Plato uses conversation to illustrate two points: first, we need to spend at least some of our time in serious, sustained conversation and reflection with others. Second, when we do so, we need to follow the argument where it leads and not just where we want it to go.

|

| A brook trout I photographed in Maine. |

*********************

[Images: Raphael's "School of Athens," showing famous Greek philosophers "at work"; two mayflies photgraphed in the summer of 2009 in Gravenhurst, Ontario; one of the tributaries to Lake Muskoka in Ontario; a brook trout photographed on the Magalloway River in Maine, 2009 while fishing and doing some research with Matt Dickerson. The Raphael image is in the public domain; the others are my own photos. I think mayflies are especially lovely creatures. The adult stage shown above is a very brief period of their lives; most of their lives are spent underwater, and their appearance is quite different then from what it is as adults.]