Uncategorized

- The passage from the novel is from Laura Ingalls Wilder, Little Town on the Prairie. (New York: Harper Collins, 1971) 198-199.

- The passage from Laura Ingalls Wilder's letter to her friend can be found here: LIW to Miss Weber, 11 February, 1952. Cited in Ann Romines, Constructing the Little House: Gender, Culture, and Laura Ingalls Wilder, University of Massachusetts Press, 1997. p.233.

Teaching Tropical Ecology in Belize and Guatemala

|

| Sunrise on the Barrier Reef in Belize |

In this post I'll try to answer some of the questions that we are often asked about the course. Probably the most common question is "What do you do in your course?" The second most common must be "How can I teach a course like that?" I'll start with the first question:

What do you do in Guatemala and Belize?

The short answer to this question is a lot. I'll try to summarize.

Our approach to tropical ecology includes the standard elements you'd find in any ecology course: our students read a lot about the ecosystems and the prominent species of plants and animals they're likely to encounter. We teach them what we know about the systems we think we understand, and we tell them about the big gaps in our knowledge that we're aware of - knowing full well that we likely have blind spots we aren't aware of.

In Guatemala this means learning about the ecology of a dense forest growing on a karst plateau, and a deep lake where the water does not circulate much.

In Belize we study the mangroves and the barrier reef. The mangroves are like a porous filter between salt and fresh water, like a cell wall on a macro scale. They serve as a buffer against hurricanes; they keep topsoil from eroding into the sea, and they are a rich and colorful nursery for thousands of species.

The Importance of Human Ecology

We want our students to learn much more than the plants, animals, soil, air, and water, though. Perhaps more than anything, we want them to learn the human ecology of the places we visit. Ecology is not merely an academic study; it is, at its heart, the study of both the world and of our place in it. We don't just look at macaws, jaguars, vines, and ceiba trees; we look at the way our lives - even our visit to these amazing places - affect and are affected by these plants and animals. We don't stay in hotels; we rent rooms in local homes, and we eat meals with local people. We hire local teachers to teach us Spanish and the Itzá language. We study the history of the Itzá people, and we visit ancient ruins. We walk through the forest and camp overnight with local guides who can teach us what they know of that place. We spend time playing soccer with a local youth group, we talk with and listen to local teachers, nurses, physicians, forest rangers, ecologists, NGO volunteers, government officials, town elders, and children. If the ecology of the place matters, surely it matters because these people whose ancestors have lived there for so long matter.

|

| Tikal |

|

| The church in San José, Petén, Guatemala |

In fact, even if you think they don't matter to you, if you're reading this post in North America these people do matter to you. If their ecology suffers, they will be forced to move to look for new sources of income and food. Simple-minded and disingenuous politicians will tell you this is a problem to be solved by erecting a wall on our border, but walls are a partial solution at best, and at worst, they are blinders that keep us from seeing the source of the problem; walls ignore the real illness and conceal the symptoms, as though willful ignorance were good medicine. The real question - in my mind, anyway - is why anyone who lived on the shores of Lake Petén Itzá would ever want to leave. The answer is that people leave beautiful homes when those homes cease to be liveable. Which means the medicine that is needed is one that treats the illness itself, and not just the symptoms. My students (I hope) return from our course no longer able to see Guatemalan immigrants to the United States as a mere abstraction. Break bread in someone's home and you will see that they are human, too, with lives as particular and intricate and important and rooted as your own. Only when we disturb those roots and strip away the soil must the lives be transplanted.

This is what I mean by human ecology.

|

| One of my students examining and being examined by nature |

Where do you go?

Our time in Guatemala is chiefly in central and northern Petén. Until recently, the landscape of northern Petén was dominated by dense forest, mostly old-growth lowland forests. Surface water is mostly wetlands that vary considerably from one season to the next. There are several small-to-medium-sized rivers, and small streams, but I think a good deal of the water flows underground in karst formations; the Petén has thin soil over a wide karst plateau. There is not much water flowing on the surface. In the center of Petén there is one very deep lake, Lake Petén Itzá. This is a gem in the forest. Flying over it on a sunny day you can see the shallows fade from pale green to rich emerald, and the depths along the north side of the lake plunge to amethyst and dark sapphire. The lake has no obvious inflow or outflow, except a few small streams flowing in from the south and west, and a little creek flowing out in the east.

|

| My students leap into Lake Petén Itzá to cool off. |

In Belize we spend most of our time on one of the barrier islands that have no permanent residents. We use that island as a home base from which we can boat out to patch reefs, mangroves, turtle grass beds, deep channels, and the fore-reef. We snorkel with our students in all these places, slowly gathering experiences of similar species in diverse environments, so that the students (and we) can see both the ecology of small places and the web of relations between those small places. In mangroves, for instance, we might see juvenile caribbean reef squid that are a few inches long. When we see them on patch reefs, they might be five or six inches long, and in deep water they might reach eight inches. Each location gives us a glimpse of another stage of their life cycle.

|

| My students watch the sunset in Belize |

Why do you do this? Aren't you a Humanities professor?

Even if people don't often ask me this, it's obvious that quite a few people think it. Yes, I'm a professor of philosophy and classics, and I teach religion courses, too. But for my whole life I have been fascinated by life underwater. My most recent book was the result of eight years of researching the lives of brook trout in the Appalachian mountains, and much of my research now has to do with ocean and riparian environments in Alaska. I don't do much of what would count as research in the natural sciences, but I do spend a lot of time observing nature. This is both because I find it beautiful, and because I think it's a bad idea to try to formulate ethical principles about things I haven't experienced or seen firsthand. Of course it's not impossible to write policies about things one hasn't done; one needn't commit larceny before writing a law prohibiting theft. But experience teaches me things I might not learn in other ways, and that can keep me from trusting too much in my own opinions. As Aristotle put it,

“Lack of experience diminishes our power of taking a comprehensive view of the admitted facts. Hence those who dwell in intimate association with nature and its phenomena grow more and more able to formulate, as the foundations of their theories, principles such as to admit of a wide and coherent development: while those whom devotion to abstract discussions has rendered unobservant of the facts are too ready to dogmatize on the basis of a few observations.” Aristotle, De Generatione et corruptione, 316a5-10 (Basic Works, McKeon, trans.)I want to "dwell in intimate association of nature and its phenomena," and being able to formulate better principles is a nice side effect of doing so.

How Can I Teach A Course Like This? Can others participate in this trip?

The answer to the second of these questions is both yes and no. When I'm in Guatemala and Belize, I'm teaching. Unfortunately, this means I don't have time to bring others along and act as their tour guide.

However, the people I work with in Guatemala - the Asociación Bio-Itzá - would be happy to have you come for a visit. They're in the small town of San Josè, Petèn, Guatemala, right on the north shores of the lake. And this is the answer to the first question. Want to teach such a course? Get in touch with Bio-Itzá and they can help you set it up.

You can get to San José by flying or driving to Flores, then going around the lake by bus or car to San José, about a twenty minute drive.

|

| Flores, Petén, Guatemala |

In San José they have a traditional community medicinal garden. Just north of town is the Bio-Itzá Reserve, where you can go for guided walking tours or overnight stays. It's rustic and gorgeous. (Visits to the Reserve must be arranged in advance through Bio-Itzá.)

When you stay in San José you can easily take a launch (a wooden motor boat) across the lake to Flores, the seat of Nojpetén or Tayasal, the last Maya kingdom that fell to the Spanish.

Flores is a pretty place as well, and I like to take my students to visit ARCAS to see their animal rehabilitation center. (There's a great documentary about that place that was on PBS this year called "Jungle Animal Hospital.")

|

| Scarlet macaws being rehabilitated at ARCAS so they can be released back into the wild |

If you stay in San José, you can also take a short trip (about a half hour by car) to Tikal, or to Yaxhá, both of which are amazingly well-preserved Maya ruins. A little further past Tikal is Uaxactún, where you can see more ruins, and you can also visit a community that is trying to practice sustainable forestry.

This region is not like the tourist areas of Western Guatemala; it's more like the rural frontier of Guatemala, a long-neglected place that is now at risk of being overrun by slash-and-burn forestry, cattle farms, and oil development. It makes me think of the Dakotas over the last century; the population is small and indigenous, and most people in power in Guatemala seem to consider the forest to be a wasteland that is better burned down than preserved. I do not share that view, and while I know that more tourism will bring development and other risks to both culture and forest, the risks are already there in other forms. I hope that ecotourism will offer some counterweight to the other kinds of development that don't seek to preserve the biological integrity or cultural history of this place.

Butterflies In My Stomach

|

| Kentucky roadside butterfly banquet. Can you see the little one? |

Here is the danger of becoming a professor of Environmental Humanities: people begin to assume that you care about nature, and that you are willing to share what you know.

Both of these things are true, by the way. (Many of my photos of wildlife and nature are here, on my Instagram account. I do care, and I am delighted to share the little I know.)

Over the years, I have come to love insects. This has come about partly through my years studying trout, char, and salmon, and of the places they live. I've spent a good portion of the last decade walking Appalachian waterways from Maine to Georgia. Over that same time, I've walked hundreds of miles through the remaining forests of northern Guatemala and Nicaragua. As both a researcher and teacher I've walked through the mountains of the American West; and I've made similar excursions to the foothills of the Brooks Range, the Kenai Peninsula, and Lake Clark National Park in Alaska.

The fish that I love depend upon the insects, so, like so many people who gaze at salmonids, I have come to know many riparian insects.

Once you study the insects along the streams, you start to notice the other plants and animals that depend upon them, too. In Kentucky I have come upon a steaming pile of bear scat that was full of half-digested cicadas. I've started to notice the wings of insects, left behind by the birds that only eat the fleshy bodies of the bugs they catch.

|

| Butterfly wing, left behind by birds. Guatemala. |

From there, it's not a big leap to realize that if the fish and the birds and the plants need the insects, then so do I. Butterflies and other insects feed the larger animals my species eats, and they pollinate the plants that feed us. All of us have the actions of butterflies in our stomachs. Can you see the lepidoptera in this next photo? There are quite a few of them, resting on the bark of this tree in Petén.

|

| Gray cracker butterflies, Petén, Guatemala. |

Little six-legged creatures feed us all. The small things matter.

And so do my students, even if they're not currently enrolled in one of my classes.

So in the past week I’ve gathered a few hundred of my best butterfly photos to share with my student. This photo is one of the worst in photo quality, but it’s a great image nevertheless:

|

| Butterflies on the ground in Kentucky, 2008. |

I took this nine years ago in the mountains in Kentucky while working on my book on brook trout. Three distinct species of butterflies are gathered here, sipping minerals from the ground. My coauthor Matthew Dickerson and I came upon this arboreal banquet by chance.

I wish I'd had a better camera with me. For now, the blurry image is enough to bring to mind that memory of hundreds of lepidoptera sipping and supping together on the forest floor, filling their bellies with the bare earth before flying off to pollinate flowers that, through a complex net of relationships, would someday fill my belly too.

Wicked Problems in Environmental Policy

a. Do so for their perspectives, for their interests, and for their tools.

b. Ask: Who are the stakeholders?

i. Go beyond the financial stakeholders or stockholders.

ii. Include everyone who affects, or is affected by, the policy under consideration.

c. Remember Charles Peirce’s idea: science is the work of a community, not of an individual.

d. Make concept maps, and use other kinds of visualizations of the problems.

i. This is a way of utilizing a broad range of tools. Don’t just use the tools others tell you are relevant; include the arts and the sciences alike.

ii. Drawing and sketching pictures will help you to see better. As Louis Agassiz said, “the pencil is one of the best eyes.” It is often better than a camera.

iii. Music, literature, poetry, and the visual arts may be just as helpful as the tools offered by STEM fields and policy-making professions like law.

iv. If you include the arts, you wind up including the artists; similarly, if you exclude the arts, you exclude the wisdom and insight of the artists.

v. Include ordinary daily practices. Learn to fish, even if you don’t plan to fish. Hike in the woods, even if you don’t like the outdoors. These are, in a way, practices of paying attention to the world.

e. Include other voices and texts in the conversation, not just the shareholders, but all the stakeholders.

f. Define “stakeholders” as broadly as you can. Include a community across generations. Include the departed and the not-yet-born if possible.

i. Traditions might be full of wisdom, so don’t ignore them, especially if they are specific to a place. Traditions may be inarticulate wisdom that is tested by time.

ii. Plan for seven generations. I sometimes think of this as the difference between planting those crops you will harvest this year and planting hardwood trees so that they will be old-growth trees long after you are dead. Humans – and other species – need both kinds of plants.

|

| Bear scat along a salmon river, Katmai Preserve, Alaska |

2) Second, fill your toolbox—and your community’s toolbox—with bear poop. This is an inside reference my students will understand by the end of the semester, but I'll fill you in briefly: I take the time when I am in the wild to look at animal scat, because it is often a picture of what food is available to the animals, and that, in turn, is a picture of the problems the environment is facing. Paying attention to scat over time gives you a long-term picture of changes to the environment. Poop is a tool that is free, that is right in front of you, and that is easy to overlook as unimportant or distasteful. Bear poop that is full of salmon bones tells me one story; bear poop that is full of berries tells me another. I don't literally fill my toolbox with bear poop, but paying attention to negligible things like bear poop gives me new tools I wouldn't have otherwise. What does this mean for us?

3) Third, have what Peirce calls “regulative ideals”

4) Fourth, don’t expect perfection

5) Fifth, do expect growth, and strive to cultivate good things. This is the work of ethics.

6) Sixth, do expect to be part of a community that continues to work on the problems for a long time.

7) And seventh, don’t give up!

The Ethics of Automation: Poetry and Robot Priests

In terms of ethics and law: who has access to the information confessed, and what is the legal status of that confession? Is there anything like the privilege of confidentiality enjoyed by clergy who hear private confessions from their parishioners?

“The making of things is in my heart from my own making by thee; and the child of little understanding that makes a play of the deeds of his father may do so without thought of mockery, but because he is the son of his father.”

Might it be possible for us also to make sentient life in imitation of God "without thought of mockery," and, if so, might it be that those lives we make could write poems and become priests? As anyone who has read Tolkien's myth knows, this raises a new set of ethical questions that now have to be resolved.--J.R.R. Tolkien, Silmarillion, p 43

*****

Update, 22 May 2018: Irina Raicu just published a very thoughtful reply to this, entitled "Parenting, Politeness, Poets, and Priests" at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University. Her article is very much worth the time it will take you to read it. You may find it here.

The Trace I Left Behind

Sometimes I get quizzical looks when I say that I, a philosophy and classics professor, am researching fish. Let me explain.

I teach environmental philosophy and a range of classes in what I call "environmental humanities." These include courses in environmental ethics, nature writing, philosophy of nature, and even a course on environmental law and policy for first-year undergraduates, as an introduction to being a university student.

I also teach courses in field ecology, including a monthlong course in tropical ecology in Guatemala and Belize. I teach in Greece over my spring break, and this year we will be looking at the expansion of fish farms in the Mediterranean and how fishing has changed there over the last six thousand years.

Closer to home, I teach and practice what Norwegians call friluftsliv, or life in the free air. Whenever possible, I teach outdoors. Most years, I take my ancient philosophy students camping in the Badlands National Park to watch the Orionid meteor shower while we lie on sleeping bags under the stars.

In all of this, my aim is to make sure that nature is not an abstraction to my students, nor to me. I want to know the places the fish live, the grasslands the bison roam, the forests where the jaguar and the ocelot hunt, the tundra rivers where the Dolly Varden chase the salmon under the watchful gaze of the bears.

In other words, my aim is to stay in contact with wildness, and to do so in a way that allows me to take something valuable home: intimate knowledge. I am not a scientist, so I don't bring samples back to a laboratory. I do bring home photographs, and I do spend a lot of time making observations of the places I work, so that I can bring home notebooks full of writing to share with my students. And of course, I write books and articles to share with others.

This summer, I was sorely tempted to bring something else home from Lake Clark: a tiny fossil. I had chartered a float plane to take me to a fairly remote lake, and there my fellow researchers and I walked the shore to the mouth of a stream full of spawning salmon and rainbow trout.

|

| Salmon preparing to spawn |

As I often do, I sat down on the gravel and started to turn over rocks to see what invertebrates were living there. The salmon are bright red and eye-catching, but the bugs and spiders tell an important part of the story of a place, as Kurt Fausch has written about in his recent book, For The Love Of Rivers. Who was it - J.B.S. Haldane, perhaps? - who quipped that God has "an inordinate fondness for beetles." The world is full of wonderful, tiny lives that are easy to overlook.

I don't try to bring beetles home, but one insect tempted me this summer. Really, it was just a trace of an insect, just the trace of its wings, in fact. I can't even tell you what insect it was. All I can tell you is that somewhere near that river, probably millions of years ago, something like a dragonfly died in the mud, and the river graced its delicate wings with the cerement of silt. That silt took the form of the wings, those wings left a fingerprint - a wingprint - on the earth. And this summer, I found that print, that delicate, wonderful trace.

|

| Fossilized trace of an insect's wing |

While my son and my friend and our pilot walked, I sat with that stone in my hand and thought about pocketing it. Here I was in the wilderness, and no one would know. It's one tiny stone in the largest state in the union; who would miss it?

Ah, but it is one tiny stone that does not belong to me. It is one tiny stone in a vast wilderness that belongs to all of us, and to all who will come after us. It is one tiny piece of rock with an incomplete fossil of a little odonata. The river there has held it and cared for it since time immemorial.

Now I am back in South Dakota, but a tiny trace of my heart remains along the strand of that stream in Alaska. It lies there, wrapped around that delicate trace of insect wing, and I will never find it again in that vast wilderness.

But perhaps someone else will. Until then, perhaps it is best not to let Midas' longings turn our hearts to stone too soon. Let's walk the shores together, I will continue to say to my students. And let's bring something intangible home in our memories. And let's do the hard work of leaving behind the beautiful, delicate traces that wildness has safeguarded for so many, many years.

The Sentiment That Invites Us To Pray - Peirce on Prayer and Inquiry

Read the rest here, in the latest volume of the Journal Of Scriptural Reasoning.

Bluejay Linings

stay together

learn the flowers

go light

What's In A Name? Almanzo Wilder and El Manzoor

It's worth remembering that act of kindness shown to a Crusader, by a man with a Persian name. The Wilder family remembered that act centuries later. ("Manzoor" and variants of it are fairly common in Iran today. For example, the kind and brilliant former Director of the Toronto and San Francisco Operas, Lotfi Mansouri, was born in Iran and educated in California.)

This story makes me wonder: how might I live my life in such a way that another family will be glad to remember me a thousand years from now?

You can read the full text of my short essay about Almanzo and El Manzoor in today's Sioux Falls Argus Leader.

Since the essay in the Argus doesn't include my footnotes, here are the relevant citations:

SPUnK: The Society for the Preservation of Unnecessary Knowledge

James is a Philosophy and Classics major at Augustana University, and he's also the Prime Minister of SPUnK, a campus group I advise at Augustana University.

SPUnK - the Society for the Preservation of Unnecessary Knowledge - is devoted to learning about things we don't need to learn about, because we think unnecessary knowledge is worth preserving and promoting. We distinguish between those things students are told they must study in order to get a job, and those things that we study because there is delight in wonder, and in learning new things, even if we don't yet see their practical use. As both Plato's Socrates and Aristotle pointed out, the love of wisdom begins in wonder, and we seek knowledge not for some simple or material gain but for the satisfaction of wonder and out of a desire to know. Here's Aristotle:

"Now he who wonders and is perplexed feels that he is ignorant (thus the myth-lover is in a sense a philosopher, since myths are composed of wonders); therefore if it was to escape ignorance that men studied philosophy, it is obvious that they pursued science for the sake of knowledge, and not for any practical utility.The actual course of events bears witness to this; for speculation of this kind began with a view to recreation and pastime, at a time when practically all the necessities of life were already supplied. Clearly then it is for no extrinsic advantage that we seek this knowledge; for just as we call a man independent who exists for himself and not for another, so we call this the only independent science, since it alone exists for itself."*Or, as Charles Peirce once put it, science is the practice of those who desire to find things out.**

This is what SPUnK is all about.

James and Hugh will teach you about paper towns, curiosity, education, Abraham Flexner, Albert Einstein, Rubik's Cubes, and other unnecessary knowledge. It's a short interview, well worth a few minutes of your time. Unnecessary knowledge is worth quite a lot more than a little of our time, after all.

* For two places Plato and Aristotle say this, see Plato's Theaetetus 155b and Aristotle's Metaphysics 982b.)

** Peirce writes about this in the first chapter of Justus Buchler's The Philosophical Writings of Peirce.

Babel, in Paraphrase

Seeing often requires unhasty attention, or training, or both. I can't claim to have training in architecture, but I am trained in semiotics, and I suppose some of my grandfather's years as a toolmaker and my father's career as an engineer have rubbed off on me. Whatever the cause, I care about design.

The ancient story of the Tower of Babel (found in the eleventh chapter of the Book of Genesis) is also a story about design, and semiotics.

It's also a story worth unhasty attention. One hasty version goes roughly like this: everyone on earth shared a common language and common vocabulary. The people, moving to a new place, decided to build a tower to heaven, so they baked bricks and began to build. But they did not finish it; their language became many languages, and they spread out in many directions, divided from one another.

The Bible has a number of stories like this, short tales that seem to be making some simple and clear point. But as we ponder them unhastily - which is what theologians often do - we become more aware of how little we know. The obvious becomes the obscure, and the quotidien becomes mysterious.

A simple story becomes an invitation to slow down even more, and to consider. Selah, it says to us.

At first blush, the story of Babel appears to be a story of human hubris, and of God frustrating that hubris. It could be a simple parallel to the expulsion from Eden, or to the flooding of the earth in the story of Noah: there are limits, and if you transgress those limits, you will make your lot in life worse.

The passage in Genesis 11 talks about bricks as a substitute for stone. When I was young I often worked as a stonemason and bricklayer. That experience may be what draws me to this passage. Bricks are easy to make, and easy to cut. We can standardize them, which makes building walls much faster.

The downside of bricks is related to their upside: they're easy to break, or to cut, or to erode. They don't last as long as stone, and if they're not well-reinforced, they are not as resilient against natural disasters. Some ancient stonemasons figured out how to cut and lay stones that can be jostled by an earthquake and then settle back into position, but bricks often collapse when the ground shakes beneath them. Bricks are easy to use, but they are not as reliable as stone. In comparison to many kinds of stone, bricks are a short-term investment.

This makes me wonder: what was the problem with the Tower of Babel? Was it the fact that the people were trying to build a tower to heaven? Or was it that they were trying to build one badly, or cheaply, or fast? Was it a problem of hubris, or a problem of materials and design? Genesis 11 does not answer that question directly. It leaves it as an open question for us.

Which is just what we should expect, if Genesis 11 conveys any truth. Think about this: how would this story have been told before the Tower of Babel was built? If the story is right, then before the Tower was built, the story would have been told in a language everyone would understand. But now that we have tried to build it (whatever that means) the story must be told in words that are confused, for people who are scattered and divided and who do not share vocabulary.

To paraphrase this: somehow, our use of bricks resulted in making it harder to connect with one another. And it's not clear how.

But somehow, it is a story that hundreds of generations have found worth repeating, even if our words fail to say with precision why that is so.

Maybe, just maybe, it has something to do with the way we continue to build walls of bricks. And what those bricks say about us, and what we value.

Since writing this, I started reading Christopher Alexander's book, The Timeless Way of Building, recommended to me by some friends in Sioux Falls. This line in particular stands out as serendipitous:

"But in our time the languages have broken down. Since they are no longer shared, the processes which keep them deep have broken down: and it is therefore virtually impossible for anybody, in our time, to make a building live." (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979) p. 225

A Pretty Good Year

As my regular readers know, I'm a professor of philosophy and classics, and I teach a wide range of classes. (You can click on the "Teaching" link above to see a sampling of the courses I teach.)

Often people assume that means I wear tweed and a bowtie and that I spend my time in classrooms talking about old books. All that is true, but it's only a part of what I do.

In fact, most of my favorite classrooms are outdoors, where I'm likely to be found wearing jeans and hiking boots, a parka, or a wetsuit and snorkel.

Over the last dozen years or so my teaching and research have tended towards the environmental humanities. Think of this as the merging of the humanities side of the liberal arts with a close observation of the natural world. I consider my work to be a continuation of the work that Thales and Aristotle did when they paid close attention to animals on the ground and to the skies above, and of the work of Peirce, Thoreau, and Bugbee, all of whom let a rising trout or a solar eclipse provoke philosophical reflection.

While I don't work in an indoor laboratory, I think that education is not about the imparting of information or the filling of an empty vessel with ideas. Education is the kindling of a fire, as Plutarch wrote. And that fire is kindled by the kinds of experiences that we get in labs, art studios, shared meals, liturgies, study travel, and seminars. Lecture halls are a fine place to discuss environmental policy, to be sure. But so is a prairie, especially when you're waiting for water to boil on your camp stove, and watching the sun's beams break over the horizon and melt a light frost on your tent.

When I'm at home, I like to take my classes outside to sit under trees on campus. In the fall, I try to bring my Ancient Philosophy students camping in the Badlands of South Dakota where we can view the stars far from urban glow. Most Januaries, my students and I are in the subtropical forests of Guatemala and on a barrier island in Belize, studying ecology and culture. I rarely take a spring break, since I usually take that week to teach a course in Greece. Last summer I started teaching a class on trout and salmon in Alaska.

Those are all beautiful, memorable places, but I don't visit them as a tourist. I go to these places because I want my students to understand what is at stake when we talk about environmental regulations and practices. I want them to meet displaced people whose permafrost islands are melting or whose forests are being burned down for meager cropland. I want them to see the disappearing mangroves so that they can consider the full cost of seafood. When they stay in homes in Guatemala, my students will meet people who can never again be a mere abstraction; after we return, my students will know that the people struggling to cross borders are not nameless, faceless strangers, but people who are looking for ways to feed those they love.

A little less than a year ago I was finishing up a year that had brought me to all these places. I taught in the South Dakota Badlands, in Central America, in Greece, and in Alaska. Along the way, I had begun studying environmental law at Vermont Law School as a way of enhancing my teaching and my research. It was a good year, and as August was winding down, my desk was covered with field notebooks full of observations from Alaska and Guatemala, ready to be written up. My field notes are usually accompanied by thousands of photographs, and hundreds of sketches. I began the fall semester last year ready to teach, and ready to write.

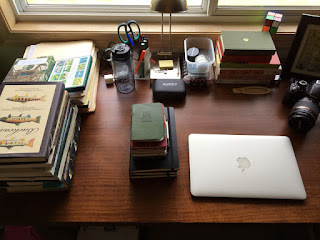

|

| Field notes. A picture of some of the work I do when I'm inside, and not teaching; or, if you like, a picture of my desk as I recover from my injuries. I have a lot of catching up to do. |

And then I wound up in the hospital with some serious injuries. Those injuries put a sudden stop to all my teaching last fall, and for a long time I lost most of my ability to write. (I'll try to write more about the injuries and my subsequent disabilities later; it's not an easy thing to write about yet.)

Now, as this summer hastens towards the beginning of another school year, I am able to look back on last year with a sense of good fortune - albeit mixed with one very bad day and its long-term consequences. Physically, I'm regaining my flexibility and strength, a little at a time. I'm not where I was a year ago, and I may never be there again, but I'm alive and able to walk, so I'll count that in the "win" column of my life's scorecard. Intellectually, most people seem to think I'm doing fine, so I'll also count that as a win. Although it left me exhausted each day, I was able to teach again this spring, and I plan to be back in my classrooms (Deo volente!) this fall.

But here are these field notebooks, and hundreds of unedited pages on my hard drive. It was my habit to write daily. Over the last year, recovering from a brain injury has made it hard to write more than a few sentences at a time.

This morning I was looking at some of my pictures from my research in the Arctic last summer, and I was hit with a feeling of loss. Those photos and those notes should be a book by now, and perhaps several articles and book chapters, too. Instead, over the last year, as I have waited for my body and brain to heal, and as I struggled to do my teaching, I had no strength to write.

It feels funny to say that, but perhaps I am not alone in finding that a brain injury can be slow to heal and extremely tiring. I don't say that to get your sympathy. I am blessed with a very supportive community and an amazing wife who somehow has kept our life together and nursed me through my healing process. I'm fortunate. But if you've read this far, you might consider whether there are others around you who look like they're doing well physically but who might be nursing invisible wounds or who might be struggling to cope with invisible disabilities. This past year has given me a new perspective on that by making me aware of my own disabilities, most of which you won't notice if you see me at the gym or in one of my classrooms.

I might not be able to write another book yet, so for now, here's my plan: I'll write a little at a time. Thankfully, I've got my notes, sketches, and photos. I'll start with them.

If you're curious about how a professor of philosophy and classics does research and writing about nature - and how he works to recover from a serious brain injury - you might check out some of my recent publications. My book Downstream is the result of eight years of field research on the ecology of the Appalachians, with a focus on brook trout. On this blog you'll also find my recently published poem, "Sage Creek," which might give you a glimpse of my ancient philosophy class camping and stargazing in the Badlands. Or feel free to look at my photos on Instagram. Even when I can't teach in the field, I can still wander my garden with a hand lens and camera.

Poem: Sage Creek

Here are the first few lines:

Halfway through the fall we drive west, far from urban glow,You can read it all here.

To see the stars that we have never seen at home.

We go to the Badlands, at night, to the primitive campground

And listen to the coyotes singing from rim to rim

Of the valley where we are trying to sleep.

The voices of three packs rise like questions:

Who are you? What are you doing here?

*****

Sage Creek

Halfway through the fall we drive west, far from urban glow,

To see the stars that we have never seen at home.

We go to the Badlands, at night, to the primitive campground

And listen to the coyotes singing from rim to rim

Of the valley where we are trying to sleep.

The voices of three packs rise like questions:

Who are you? What are you doing here?

Weary from driving, observe how much you want to stay awake

Now that you are here. Explain

And give examples

From all your senses.

If the wind blows across sage, then what follows,

and how do you first know it?

What is the feeling of the prairie wind at night,

And why is it now new to you?

Dry weeds crunch under sleeping bags stretched out under the cold, living sky.

Our arms swing to point at Orionid flares.

We speak in the whispers of worshipers entering a cathedral for the first time.

How long have we lived here,

On the prairie, and never felt it on our skin, all night long?

Compare and contrast

The Milky Way.

Before tonight, you have never seen it turn.

Consider all the stars,

And the difference between reading about them and watching them slowly slip across the sky.

Wake to the feeling that it is not yet dawn, but no longer night.

With your eyes still closed, ask yourself how you saw it,

How this dry land exposes you to yourself.

For a little while, you hold your eyes closed,

And remember the bright green lines of shooting stars.

Holding still, you listen:

This is the sound of bison, breathing. Nearby

The staccato chickadee and the whirling meadowlark

Greet the new day

In this place we have so long avoided.

The prairie dogs at the edge of the campground eye us warily, and bark a warning

As we load the car for the drive home.

*****

David L. O’Hara

(2015)

Printed in Written

River, Issue 10, 2016, Hiraeth Press.

The whole issue might be available on Kindle, here.

Good Education Should Lead To Good Questions

[....]

"If the aim of education is to gain money and power, where can we turn for help in knowing what to do with that money and power? Only a disordered mind thinks that these are ends in themselves. Socrates offers us the cautionary tale of the athlete-physician Herodicus, who wins fame and money through his athletic prowess and medicine, then proceeds to spend all his wealth trying to preserve his youth. This is what we mean by a disordered mind. He has been trained in the STEM fields of his time, and his training gains him great wealth, but it leaves him foolish enough to spend it all on something he can never buy."

From my latest article, co-authored with John Kaag, in The Chronicle of Higher Education. Read it all here.

Martin Luther on Liberal Education

-- Martin Luther, “To the Councilmen of All Cities in Germany that They Establish and Maintain Christian Schools,” in AE 45:357 (1524) (emphasis added) A full translation of the letter is available here.

Thoreau on Liberal Education, Wealth, and Freedom

-- Henry David Thoreau, "The Last Days of John Brown"

Giving Thanks In The

“‘What a damned country,’ he said. Watching the river, he had not noticed the movement at the far corner of the garden below him, but now as he swung the glasses down he saw there one of the ragged, black-robed boys who raked and sprinkled the paths every day….He stood up, and Chapman stepped back, not to be caught watching, but the boy only pulled on his robe again. Then he knelt once more on the rug of his turban and bowed himself in prayer towards the east…..The praying boy was not pathetic or repulsive or ridiculous. His every move was assured, completely natural. His touching of the earth with his forehead made Chapman want somehow to lay a hand on his bent back. They have more death than we do, Chapman thought. Whatever he is praying to has more death in it than anything we know. Maybe it had more life too. Suppose he had sent up a prayer of thanksgiving a little while ago when he found his son out of danger? He had been doing something like praying all night, praying to modern medicine, propitiating science, purifying himself with germicides, placating the germ theory of disease. But suppose he had prayed in thanksgiving, where would he have directed his prayer? Not to God, not to Allah, not to the Nile or any of its creature-gods or the deities of light. To some laboratory technician in a white coat. To the Antibiotic God. For the first time it occurred to him what the word ‘antibiotic’ really meant." – Wallace Stegner, “The City Of The Living,” in Collected Stories of Wallace Stegner. (New York: Penguin Books, 1991) 524-5. (Boldface emphasis is mine.)

“We live in the Antibiotic Age, and Antibiotic means literally ‘against life’. We had better not be against life. That is the way to become as extinct as the dinosaurs. And if, as the population experts were guessing in November 1954, the human race will (other things being equal) have increased so much in the next three hundred years that we will only have a square yard of ground apiece to stand on, then we may want to take turns running to some preserved place such as Dinosaur….That means we need as much wilderness as can still be saved. There isn’t much left, and there is no more where the old open spaces came from.” – Wallace Stegner, This Is Dinosaur: Echo Park Country And Its Magic Rivers. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1955) 14.

National Park Law - Knopf and Stegner

“The people, to whom the Parks belong, should be given the full facts on which to base a judgment, whenever the question of intrusion on Park lands arises. The people, as taxpayers who foot the bill, should also know, with fair exactness, and from a responsible reviewing body, how much a reclamation project is going to cost them, whether in a Park or not. [....]

“The attitude of Americans toward nature has been changing—slowly, perhaps, but inexorably. Fifty thousand persons camped out in one Park, the Great Smokies, in a single summer month of 1954. That same summer I spent a night at Manitou Experimental Forest, in which a near-by campground, run by the Forest Service and at that moment without a water supply, was expected to be used by fifty thousand people before winter. In 1951 Glacier National Park had a half-million visitors; in 1953 it had more than 630,000. In that same year, the last for which total figures are available, Grand Canyon had 830,000 odd, Yellowstone 1,300,000, and Yosemite just short of a million. Those figures are impressive no matter how you take them. They mean that what the Parks and Monuments provide and preserve without impairment is increasingly appreciated and increasingly needed by more and more millions of American families.”

Alfred A. Knopf, “The National Park Idea,” in This is Dinosaur: Echo Park Country and Its Magic Rivers, Wallace Stegner, ed. 91-91. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1955) (Emphasis in boldface mine)