virtue ethics

∞

Racism, Samaritans, and Saints

As I've read news about recent protests on campuses across the country I've

often wondered how I could respond helpfully if I were an administrator

at one of those campuses. And I have not found it easy to answer my own

question.

The closest I've come is this: when my kids were little, I taught them that despite what others may say, there are no bad words; but there are bad uses of good words. When we use our words to hurt others or to deprive them of what they need to grow and flourish, we are using our words badly.

Plainly there are acts, institutions, rituals and monuments that foster an undeserved poor view of some of our neighbors. Those should be changed or abolished.

But I don't think that's enough, and those might be more like symptoms than the illness itself.

I think we need to work to make sure we use our words in ways that help and heal, nurture and teach. I think we need leaders (at all levels) who will take positions of leadership as opportunities to edify and promote those who have not had such opportunities yet.

To put it in simpler terms, I think we need to work harder at loving our neighbors. Jesus told a story about this once, focusing on established ethnic hatred with deep political roots. I refer to the parable of the "Good Samaritan." This parable is the best answer I've got so far to the question I have posed for myself. If you've got the power to help others, and you see others needing help, then help them without regard for what it costs you. This is not easy, but it's what I want to strive for.

What do you think? What am I forgetting? Am I too naive and optimistic? I welcome thoughtful replies that show kindness towards a wide range of readers. (If you want to simply cuss me out or insult my ignorance, please save that for a direct message, or let me take you out for a beer or coffee so you've got more of my attention. Thanks.)

The closest I've come is this: when my kids were little, I taught them that despite what others may say, there are no bad words; but there are bad uses of good words. When we use our words to hurt others or to deprive them of what they need to grow and flourish, we are using our words badly.

Plainly there are acts, institutions, rituals and monuments that foster an undeserved poor view of some of our neighbors. Those should be changed or abolished.

But I don't think that's enough, and those might be more like symptoms than the illness itself.

I think we need to work to make sure we use our words in ways that help and heal, nurture and teach. I think we need leaders (at all levels) who will take positions of leadership as opportunities to edify and promote those who have not had such opportunities yet.

To put it in simpler terms, I think we need to work harder at loving our neighbors. Jesus told a story about this once, focusing on established ethnic hatred with deep political roots. I refer to the parable of the "Good Samaritan." This parable is the best answer I've got so far to the question I have posed for myself. If you've got the power to help others, and you see others needing help, then help them without regard for what it costs you. This is not easy, but it's what I want to strive for.

*****

What do you think? What am I forgetting? Am I too naive and optimistic? I welcome thoughtful replies that show kindness towards a wide range of readers. (If you want to simply cuss me out or insult my ignorance, please save that for a direct message, or let me take you out for a beer or coffee so you've got more of my attention. Thanks.)

∞

"What We Need Right Now"

From my latest contribution to the "God's Politics" blog at Sojourners:

"Any right-thinking stranger on our shores must read our daily news and think our nation has gone mad. We have cultivated the ability to end lives quickly; and yet we are continually surprised when our fellow citizens use the tools we have devised for exactly the purpose for which we invented them. Come to think of it, I think we’ve gone mad, too."You can read it all here.

∞

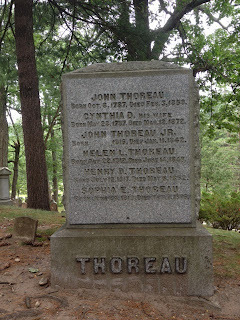

Thoreau: We Still Have Choices

“The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation….When we

consider what, to use the words of the catechism, is the true end of man, and

what are the true necessaries and means of life, it appears as if men had

deliberately chosen the common mode of living because they preferred it to any

other. Yet they honestly think there is no choice left. But alert and healthy natures remember that

the sun rose clear. It is never too late

to give up our prejudices.”

Henry David Thoreau, Walden. (New York: Modern Library, 2000) p. 8. (Boldface is my addition)

∞

Leopold On Sport And Ethics

“Voluntary adherence to an ethical code elevates the self-respect of the

sportsman, but it should not be forgotten that voluntary disregard for

the code degenerates and depraves him.”

- Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac

∞

Armed in Anxiety

My article on guns, fear, and virtue ethics, now accessible at The Chronicle of Higher Education:

What do guns do for us? Many opponents of new gun legislation argue that they make us safer. Proponents of gun control hope to promote public safety by keeping guns out of the hands of bent young men who worship projectile power and senseless death. Most of our public-policy debates about guns have focused on safety, but in my opinion, not enough has been said about whether guns make us sound.Read the rest here.

Our word "safe" has roots in the Latin word salvus, which means not just "secure from harm" but "whole, well, and thriving"—that is to say, sound. This is one of philosophy's oldest concerns, to examine and foster this kind of sound, flourishing human life. This question is at the heart of Aristotle's ethics, for example. The opening lines of his Nicomachean Ethics declare that it is possible to regard life as having a kind of excellence, a sense of human flourishing and wholeness to which all of our sciences contribute. As Aristotle puts it, failure to reflect on this will make us like people who shoot without considering their target. (Yes, he really says that.)....

∞

Surveillance and Virtue

The recent news that a no-fly zone was enacted over the site of the Exxon tar sands pipeline spill in Arkansas is in line with the movement in state legislatures to make it a crime to record animal cruelty, even when it is plainly in the public interest to do so. I recently learned it is a crime to film trains carrying nuclear waste, leading me to wonder how I'm supposed to know what any given train is carrying. So taking a family photo while a train passes in the distant background could be a felony? Bizarre.

These are signs that our technology is racing ahead of us. It is easier to create new machines for surveillance than it is to devise a set of rules for ethical use of those machines. The problem of Google Glass is not something altogether new; but the technology sharpens the ethical issues: can I wear it in the locker room at the gym? Can I wear it while talking with the police, or border guards? Can I wear it at a party where co-workers are drinking?

The problem of drones is similar: we have increased our ability to watch others without being watched. As Foucault observed, this is one of the main functions of the prison, a relatively modern invention. The prison is an architectural technology that allows us to watch over our fellow citizens without having them watch us.

The technology is helpful, and it's not patently evil. Information is power, we are told, and everyone likes power. But we should remember the Ring. The Ring of Gyges, or the One Ring of Tolkien, either one will do; in both stories, the ability to observe while unobserved, this ultimate and total camouflage, is too much power. And there is some truth to the dictum that power corrupts.

We are unlikely to slow our own technological progress, so we must devote equal energy and resources to ethical reasoning and to ethical living. Here is where I suggest we start:

First, if you're ashamed of someone seeing what your community is doing, don't do it. It is one thing to protect trademarked secrets and patented methods of production, to enjoy the economic benefits of one's creativity. But if your reason for concealing your business process is that you know I won't buy your product if I know how it's made, you deserve to be exposed because you are manipulating me by concealing information that would affect my decisions.

Second, devote yourself to respecting the privacy and dignity of others. Do this not just for others, but for yourself. We know ourselves to be less than we wish we were; and we know that the social impulse is balanced in our species by a desire to do some things alone, unobserved, or only in intimate company. To expose those things unbidden is to dominate. It is crass, and unkind. If you do not respect others, the technologies of surveillance will become your Ring, and you will destroy your own soul.

At times these two principles will be in conflict with one another - underscoring the importance of continued ethical reasoning. We can't simply fall back on facile rules. We have got to keep thinking, and thinking hard, together. The simple principles, however, can provide a good place to start: do not attempt to dominate or destroy others. Put positively: love one another.

These are signs that our technology is racing ahead of us. It is easier to create new machines for surveillance than it is to devise a set of rules for ethical use of those machines. The problem of Google Glass is not something altogether new; but the technology sharpens the ethical issues: can I wear it in the locker room at the gym? Can I wear it while talking with the police, or border guards? Can I wear it at a party where co-workers are drinking?

The problem of drones is similar: we have increased our ability to watch others without being watched. As Foucault observed, this is one of the main functions of the prison, a relatively modern invention. The prison is an architectural technology that allows us to watch over our fellow citizens without having them watch us.

|

| Be kind; love one another. |

We are unlikely to slow our own technological progress, so we must devote equal energy and resources to ethical reasoning and to ethical living. Here is where I suggest we start:

First, if you're ashamed of someone seeing what your community is doing, don't do it. It is one thing to protect trademarked secrets and patented methods of production, to enjoy the economic benefits of one's creativity. But if your reason for concealing your business process is that you know I won't buy your product if I know how it's made, you deserve to be exposed because you are manipulating me by concealing information that would affect my decisions.

Second, devote yourself to respecting the privacy and dignity of others. Do this not just for others, but for yourself. We know ourselves to be less than we wish we were; and we know that the social impulse is balanced in our species by a desire to do some things alone, unobserved, or only in intimate company. To expose those things unbidden is to dominate. It is crass, and unkind. If you do not respect others, the technologies of surveillance will become your Ring, and you will destroy your own soul.

At times these two principles will be in conflict with one another - underscoring the importance of continued ethical reasoning. We can't simply fall back on facile rules. We have got to keep thinking, and thinking hard, together. The simple principles, however, can provide a good place to start: do not attempt to dominate or destroy others. Put positively: love one another.

∞

The Pastoral And The Personal In Theodicy

Theodicies, like some virtue ethics and certain ontological arguments, are easy targets for refutation, but much depends on the way they are used.

A theodicy is an attempt to reconcile the apparent evil in the world with the alleged goodness of God, often by showing that the very goodness of God makes some evil necessary; or by arguing that the goodness of God is amplified by a certain amount of evil. In other words, the evil we experience and witness is, in the end, made to serve goodness.

When theodicies are spoken publicly and authoritatively, there is a real danger that they will be used to justify further evil. If evil serves good, and evil is easier to accomplish directly than goodness, why not practice evil?

There's also the very real danger that theodicies will isolate us from one another. Sometimes some perversity in us makes us inclined to tell someone who is experiencing fresh grief that "it's all for the good," or "it will all work out well in the end," or "your loved one is now in a better place." I would guess we do this because we do not know what else to say, and because we want the discomfort of grief banished from our presence. In which case we speak those words like an incantation, using magic to make the unpleasantness disappear. But the grief is not detachable from the griever, so to will the banishment of the mourning is to will the death of the mourner. In simpler terms, when we invoke thoughtless theodicies, sometimes we are committing human sacrifice - throwing out the mourner - in order to comfort ourselves.

In spite of this, I think there is still a place for theodicies - just as there is a place for ontological arguments - provided they originate with the believer and are not forced upon her. The mourner who chooses to believe that the dearly departed have gone to well-earned rest may believe that. That belief may be the germination of the seeds of honor and love, or the expression of grief combined with commitment to the flourishing of the memory of the beloved - it may be the fruit of the idea that the cosmos has no right to bring this love to an end. You may destroy the body, but the soul you shall not take from me.

Of course, the mourner's grief should not turn into fixed doctrine for the rest of us, either. Some things we simply don't know. Death is a horizon we pass only once, a boundary that few - if any - signs are allowed to pass over. But precisely because we do not know what comes after - because we do not even know ourselves much of the time - we may allow others what they need to endure their losses, neither forcing our justifications of evil upon them, nor denying them the explanations that may give them the comfort their hearts need.

A theodicy is an attempt to reconcile the apparent evil in the world with the alleged goodness of God, often by showing that the very goodness of God makes some evil necessary; or by arguing that the goodness of God is amplified by a certain amount of evil. In other words, the evil we experience and witness is, in the end, made to serve goodness.

|

| Roman tombs in southern Crete. |

There's also the very real danger that theodicies will isolate us from one another. Sometimes some perversity in us makes us inclined to tell someone who is experiencing fresh grief that "it's all for the good," or "it will all work out well in the end," or "your loved one is now in a better place." I would guess we do this because we do not know what else to say, and because we want the discomfort of grief banished from our presence. In which case we speak those words like an incantation, using magic to make the unpleasantness disappear. But the grief is not detachable from the griever, so to will the banishment of the mourning is to will the death of the mourner. In simpler terms, when we invoke thoughtless theodicies, sometimes we are committing human sacrifice - throwing out the mourner - in order to comfort ourselves.

In spite of this, I think there is still a place for theodicies - just as there is a place for ontological arguments - provided they originate with the believer and are not forced upon her. The mourner who chooses to believe that the dearly departed have gone to well-earned rest may believe that. That belief may be the germination of the seeds of honor and love, or the expression of grief combined with commitment to the flourishing of the memory of the beloved - it may be the fruit of the idea that the cosmos has no right to bring this love to an end. You may destroy the body, but the soul you shall not take from me.

| ||

| My great aunt and great uncle. Here lie their bodies. |

∞

So, How's The Sabbatical Going?

That's a question I've been hearing a lot this year, and understandably so. Most of my friends and my students have never experienced one. I hope that all of them have a chance to take a sabbatical someday so they can see for themselves what a gift it is. Since so many of my students wonder what I am doing when I'm not on campus, I'm writing this mostly for them. Many of them have (very sweetly!) told me they miss me. Let me assure them: it's mutual. But it has also been very good for me to take this year away from the classroom.

Sabbaticals and Long Service Leaves

By coincidence, a handful of my friends were on some sort of sabbatical last summer. Mostly they work for tech firms that recognize that sabbaticals make for more creative, more productive workers. One of them was enjoying a long service leave that Australian law mandates.

Most jobs in the United States don't offer sabbaticals, but I'm fortunate enough to have one that does. Sometimes my kids chide me for choosing a job with relatively low pay, but self-regulated time is something money can't easily buy. I think I chose my career pretty well.

I say "self-regulated time" because my sabbatical isn't early retirement or a long vacation. My job as a college professor has three basic components: teaching, scholarship, and service. A sabbatical frees me from the first of those components, and from parts of the third. More precisely, it frees me from the daily tasks of teaching and service, but I expect that at the end of this year I will be a better teacher because I've had time to do research and to tear down and rebuild some of my classes. And any college capable of taking the long view knows that faculty who take sabbaticals can render better service over the long haul.

What I've been doing

To the casual observer it probably looks like I've spent a lot of time in coffee shops and airports, and not much else. For the last three years I've devoted myself to teaching and service, giving only a little of my time to scholarship. So when I began my sabbatical my scholarly life felt like deep waters pent up behind a strained dam. Over the last few years I've sketched out five books and seven articles and book chapters. Over my sabbatical I hoped to get maybe one book and a couple of articles done. That may not sound like much, but it's fairly ambitious, given how much time it takes to do the research and to write well.

Since my job description breaks down into the three parts I mentioned above, let me say a few words about what I've been doing this year in each of those areas.

Writing: As for academic writing, so far, I've completed one book (on brook trout), and made significant progress on two others (both on the philosophy of religion). Once I get them done, books four and five are ready to go, too. I've submitted one book chapter for someone else's book, and I'm about to submit another. I've written a few book reviews for popular and scholarly journals, too. Last week I gave a lecture at the College of William and Mary on war and evil. Now I'm preparing that lecture for publication as a journal article. By the time this sabbatical is over, I hope to have at least one book under contract and two more articles sent off for review. I've also done some more popular writing, including a couple of articles on virtue ethics in the Chronicle of Higher Education's Chronicle Review - one on guns and one on the ethics of drones or UAVs. Perhaps most importantly, I've been writing every day. As you can see, I've been trying to write quickly here on this blog a couple of times a week, and I've been writing in a lot of other places as well. Like any other skill, it comes more fluidly with practice.

Teaching: I've also had the pleasure of planning some new classes, including one I plan to co-teach on environmental science and ecology, and a course for alumni I'll teach in Greece this summer with another Classics professor. And I have a whopping stack of books I've wanted to read that I've been devouring hungrily. When you're the professor, it's also good to be the student as often as possible.

Service: Even though I'm away from campus, my heart is still there. Everything I do as a professor winds up leaning back towards the classroom, which means towards my students. Nothing I do matters more than the people I do it with and for, I think. I must have written sixty letters of recommendation for students this year (which is more time-intensive than one might think). Sabbatical has also given me the chance to help some colleagues here and at other universities. I've been helping half a dozen friends who teach Classics, Philosophy, and Biology at other universities by reading and commenting on drafts of their essays and books. And I've done a lot of "double-blind" reviewing for six or seven academic publishers who want advice on whether to publish certain books or journal articles. Best of all has been time to collaborate with colleagues in far-off places, corresponding with professors and graduate students around the world about philosophy, ecology, Scriptural Reasoning, Henry Bugbee, Charles Peirce, C.S. Lewis, and other matters close to my heart. I list this as "service" but I could just as well call it "ways I've learned from other people far away."

But Have You Taken Some Time To Rest?

Yes. The word "sabbatical" has its roots in a Hebrew word, shabbath, meaning "to rest." It would be a shame not to use the time to get some rest. Last summer I spent two weeks in a writing retreat sponsored by Oregon State at their Shotpouch Creek Cabin with my friend and co-author Matthew Dickerson. We were working, but what restful work it can be to live, think, and write quietly with a friend. We spent half of each day writing, and the other half talking, hiking, fishing, wading in the ocean. We borrowed some hymnals from an Episcopal church in Eugene and spent part of each evening singing as the sun declined behind the coastal range.

On my way to Oregon, I drove my sons to the coast last summer to look at colleges, to go whale-watching, and to watch some professional soccer matches. When I got home to Sioux Falls, I joined a gym and I became my son's rec league soccer coach. This is his last year of living at home with us, and I can't tell you how grateful I am to have this time with him before adulthood takes him off on the next leg of his life's journey. Despite all the work, and travel, and writing, I've had more time with my wife and my kids, and more time for self-care. I feel much healthier and fitter now than I did a year ago. I have a feeling my family is better off for that, too.

I wish everyone, regardless of their line of work, could have an experience like this every few years. It might remind us all what matters. It's expensive, I know. I took a hefty pay cut from an already modest salary to have this year off, and thankfully our savings have been enough to get us through. (And writing and lecturing makes me a few extra ducats to send to my daughter in college from time to time or to spend on my boys at home.)

No doubt some people will read this and wonder why my college is willing to pay me anything at all when I'm not showing up to work. The answer is that some colleges still take the long view. You have to put aside your monthly planner and get a calendar that measures time and value "not by the times but by the eternities" (pace Thoreau), that looks down the years the way a carpenter holds a plank to her eye and looks down the full length of the board rather than seeing only the grain of what is nearest. Money has been spent on me this year by people who thought it worthwhile to let me stretch from my cramped pose. They have let me drink from distant streams so that I can come back nourished not just by the Big Sioux and the Missouri but by the waters of Oregon and New York and Virginia - and in some sense by the Hippocrene itself.

So that's what I've been doing. I'm sorry I haven't been around campus much. In the long run, what I've been doing should make my return to campus a very good one indeed. I can't wait to tell you more about what I've learned this year once I return.

Sabbaticals and Long Service Leaves

|

| Sabbaticals can be seasons of letting dry husks bear new life. |

Most jobs in the United States don't offer sabbaticals, but I'm fortunate enough to have one that does. Sometimes my kids chide me for choosing a job with relatively low pay, but self-regulated time is something money can't easily buy. I think I chose my career pretty well.

I say "self-regulated time" because my sabbatical isn't early retirement or a long vacation. My job as a college professor has three basic components: teaching, scholarship, and service. A sabbatical frees me from the first of those components, and from parts of the third. More precisely, it frees me from the daily tasks of teaching and service, but I expect that at the end of this year I will be a better teacher because I've had time to do research and to tear down and rebuild some of my classes. And any college capable of taking the long view knows that faculty who take sabbaticals can render better service over the long haul.

What I've been doing

To the casual observer it probably looks like I've spent a lot of time in coffee shops and airports, and not much else. For the last three years I've devoted myself to teaching and service, giving only a little of my time to scholarship. So when I began my sabbatical my scholarly life felt like deep waters pent up behind a strained dam. Over the last few years I've sketched out five books and seven articles and book chapters. Over my sabbatical I hoped to get maybe one book and a couple of articles done. That may not sound like much, but it's fairly ambitious, given how much time it takes to do the research and to write well.

Since my job description breaks down into the three parts I mentioned above, let me say a few words about what I've been doing this year in each of those areas.

Writing: As for academic writing, so far, I've completed one book (on brook trout), and made significant progress on two others (both on the philosophy of religion). Once I get them done, books four and five are ready to go, too. I've submitted one book chapter for someone else's book, and I'm about to submit another. I've written a few book reviews for popular and scholarly journals, too. Last week I gave a lecture at the College of William and Mary on war and evil. Now I'm preparing that lecture for publication as a journal article. By the time this sabbatical is over, I hope to have at least one book under contract and two more articles sent off for review. I've also done some more popular writing, including a couple of articles on virtue ethics in the Chronicle of Higher Education's Chronicle Review - one on guns and one on the ethics of drones or UAVs. Perhaps most importantly, I've been writing every day. As you can see, I've been trying to write quickly here on this blog a couple of times a week, and I've been writing in a lot of other places as well. Like any other skill, it comes more fluidly with practice.

| ||

| Snail shells grow by slow accumulation, as habits do. |

Service: Even though I'm away from campus, my heart is still there. Everything I do as a professor winds up leaning back towards the classroom, which means towards my students. Nothing I do matters more than the people I do it with and for, I think. I must have written sixty letters of recommendation for students this year (which is more time-intensive than one might think). Sabbatical has also given me the chance to help some colleagues here and at other universities. I've been helping half a dozen friends who teach Classics, Philosophy, and Biology at other universities by reading and commenting on drafts of their essays and books. And I've done a lot of "double-blind" reviewing for six or seven academic publishers who want advice on whether to publish certain books or journal articles. Best of all has been time to collaborate with colleagues in far-off places, corresponding with professors and graduate students around the world about philosophy, ecology, Scriptural Reasoning, Henry Bugbee, Charles Peirce, C.S. Lewis, and other matters close to my heart. I list this as "service" but I could just as well call it "ways I've learned from other people far away."

|

| The license plate on the rental car I had at a recent conference. |

Yes. The word "sabbatical" has its roots in a Hebrew word, shabbath, meaning "to rest." It would be a shame not to use the time to get some rest. Last summer I spent two weeks in a writing retreat sponsored by Oregon State at their Shotpouch Creek Cabin with my friend and co-author Matthew Dickerson. We were working, but what restful work it can be to live, think, and write quietly with a friend. We spent half of each day writing, and the other half talking, hiking, fishing, wading in the ocean. We borrowed some hymnals from an Episcopal church in Eugene and spent part of each evening singing as the sun declined behind the coastal range.

On my way to Oregon, I drove my sons to the coast last summer to look at colleges, to go whale-watching, and to watch some professional soccer matches. When I got home to Sioux Falls, I joined a gym and I became my son's rec league soccer coach. This is his last year of living at home with us, and I can't tell you how grateful I am to have this time with him before adulthood takes him off on the next leg of his life's journey. Despite all the work, and travel, and writing, I've had more time with my wife and my kids, and more time for self-care. I feel much healthier and fitter now than I did a year ago. I have a feeling my family is better off for that, too.

I wish everyone, regardless of their line of work, could have an experience like this every few years. It might remind us all what matters. It's expensive, I know. I took a hefty pay cut from an already modest salary to have this year off, and thankfully our savings have been enough to get us through. (And writing and lecturing makes me a few extra ducats to send to my daughter in college from time to time or to spend on my boys at home.)

No doubt some people will read this and wonder why my college is willing to pay me anything at all when I'm not showing up to work. The answer is that some colleges still take the long view. You have to put aside your monthly planner and get a calendar that measures time and value "not by the times but by the eternities" (pace Thoreau), that looks down the years the way a carpenter holds a plank to her eye and looks down the full length of the board rather than seeing only the grain of what is nearest. Money has been spent on me this year by people who thought it worthwhile to let me stretch from my cramped pose. They have let me drink from distant streams so that I can come back nourished not just by the Big Sioux and the Missouri but by the waters of Oregon and New York and Virginia - and in some sense by the Hippocrene itself.

So that's what I've been doing. I'm sorry I haven't been around campus much. In the long run, what I've been doing should make my return to campus a very good one indeed. I can't wait to tell you more about what I've learned this year once I return.

∞

The Virtue of Virtue

Virtue ethics is problematic. It certainly is helpful at times, but it is not helpful when

it names virtues that others cannot relate to; or when we use it to describe

virtues that only certain classes of people can ever attain; or when virtues

entail a metaphysics to which others are unwilling to commit. The very word “virtue” raises a

red flag for some people because it is a gendered word, rooted in the Latin vir, meaning an adult male. I often wish we had a better

translation of the word Aristotle first used, arête, which means something like “excellence.”

At any rate, virtue ethics may have great value if we allow

Aristotle’s description of arête to

be a moving target, and if we appeal to it as an approach to governing our own

conduct rather than as a way to make rules for others. (Isn’t it the case that so often we

write rules for others rather than for ourselves? That should tell us something.)

Aristotle tells us that virtue is the mean between extremes,

as the man of practical wisdom would determine it. But which of us is the man of practical wisdom? No one of us has that down. So no one of us may be expected to

understand virtue exactly. This

would appear to be an argument for a collective decision, and to some degree it

is. Our public deliberations about

ethics, about methods of research, about law, about public conduct – all of

these are, in a way, attempts by groups of people to figure out what a truly

wise and prudent person would do.

So to some degree, communities and their traditions are

embodiments of decisions about virtue.

We must remember, however, that we’re always on the move, ever seeking,

never fully finding.

I am reminded of Kierkegaard’s citation of Lessing in

Kierkegaard’s Concluding Unscientific Postscript:

We live lives of unknowing, ever striving for what we might know. "Now we see as in a glass, darkly; now we see in part." And that's not so bad, is it? Peirce might call the belief that we don't know fully a regulative ideal; or I suppose, in Rorty’s terms, we might call it a pragmatic hope. If we take ourselves not to have arrived at perfect justice yet, that belief will drive us to keep seeking to improve our justice.“If God held all truth enclosed in his right hand, and in his left hand the one and only ever-striving drive for truth, even with the corollary of erring forever and ever, and if he were to say to me:--Choose! I would humbly fall down to him at his left hand and say: Father, give! Pure truth is indeed only for you alone!”*

You’ve read this far, so you’re probably ready for me to

make my point. Here it is: as we

talk about policies and politics, rules and laws—in short, when we are deeply

concerned with governing others—let us not neglect governing ourselves, by reflecting on, and trying to enact, virtue in our decisions. Life is uncertain. We do not know what will come next,

what we will be given, what will be taken away. But no one can take away the small decisions we make, the

small decisions that, one by one, make us.

******

*Soren Kierkegaard, Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992, Vol I) 106. The quotation is a citation from Lessing by Kierkegaard.

******

*Soren Kierkegaard, Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992, Vol I) 106. The quotation is a citation from Lessing by Kierkegaard.