Wendell Berry

∞

2) Second, fill your toolbox—and your community’s toolbox—with bear poop. This is an inside reference my students will understand by the end of the semester, but I'll fill you in briefly: I take the time when I am in the wild to look at animal scat, because it is often a picture of what food is available to the animals, and that, in turn, is a picture of the problems the environment is facing. Paying attention to scat over time gives you a long-term picture of changes to the environment. Poop is a tool that is free, that is right in front of you, and that is easy to overlook as unimportant or distasteful. Bear poop that is full of salmon bones tells me one story; bear poop that is full of berries tells me another. I don't literally fill my toolbox with bear poop, but paying attention to negligible things like bear poop gives me new tools I wouldn't have otherwise. What does this mean for us?

Wicked Problems in Environmental Policy

When I first started teaching environmental philosophy courses I used anthologies of helpful articles for my core readings. These included articles about topics ranging from environmental ethics and philosophy of nature to animal rights, land ethics, and pollution.

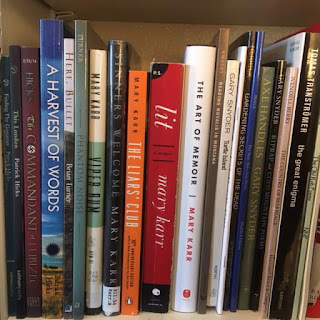

The more I read, the more I realized how hard it is to do more than a simple survey of problems in a single semester. From early on, I started adding narratives to my classes, using texts by people like Wendell Berry, Aldo Leopold, Rachel Carson, Henry Thoreau, Kathleen Dean Moore, and Vandana Shiva. I've also included sacred texts and poems from around the world, because while many of those narratives and poems don't solve the problems, the form of writing they use makes them a flowing spring of renewable thought-provocation.

Recently I've taken on an even broader approach to teaching environmental humanities courses by designing a course I call "How To Begin To Solve 'Wicked Problems' In Environmental Policy."

I won't explain everything here, because the topic is too big to explain in detail now, but I will try to explain what I mean by the title of the course.

The previous sentence is a picture of what the course is like: there's too much to cover all at once; there are too many elements to explain to do them all justice in a short space; so it's often more helpful to begin the process and to keep it before you as an ongoing matter than to treat it as a simple problem to be solved with a simple solution.

This is the nature of "wicked problems," after all. It's not that the problems are wicked or evil, but they are immensely complex, with many changeable parts or situations, and any solution that is offered will change the situation. An example might help to illustrate what I mean. Let's consider world poverty.

If we take poverty to mean simply the lack of funds on the part of the impoverished, then it is a simple problem to solve (even if it isn't an easy one.) All you have to do is find out how much money the poor lack, and give it to them. If poverty were simply a lack of funds, then filling that lack with funds would be the solution. But this solution fails to ask what caused the lack of funds in the first place, or why it matters. And it fails to acknowledge that handing over money changes the situation into which the money is given. Economists know that economic predictions are not a precise science. There are simply too many factors at play in human economic systems. As the 17th-century philosopher Mary Astell put it, "single medicines are too weak to cure such complicated distempers." [1] Some medicines have side effects, after all, and the same is true in economics, and in many other disciplines.

So how do I teach this course? I start with some problems I understand too poorly and some narratives that I know will be incomplete, focusing on two places where I teach and do research: Guatemala's Petén Department, and the headwaters of the Bristol Bay region of Alaska. In both cases, there is competition for certain resources, and the use of one resource can threaten or permanently impair other resources.

I don't expect my students can solve these problems for other people, but they are problems I've come to know more and more intimately over years of firsthand experience of the regions in question. So I tell my students stories about those places, and I try to introduce them (often by video calls) to people who work in those places. I want my students to get to know as many different stakeholders as possible, and to hear their stories in the context of those peoples' lives.

You might justifiably ask: if I don't expect my students to solve the problems, and if I myself don't have the solutions, what justifies teaching such a course? My answer is, first, that it is better to try than not to try, and second, that in looking at problems in which we don't feel a personal investment we can often learn to tackle the problems that are closer to home.

There's an ethical and political upside to this, too: once you see that certain problems are "wicked problems," you can start to see the ways that policy-touting charlatans try to pull the wool over your eyes. It is a very old political trick to win votes by claiming that wicked problems are simple ones, and that only you or your party can see the simple solution. This gives a strange comfort to voters who have been perplexed by complexity, and that comfort wins votes on the cheap, at the expense of humility, neighborly care, mutual struggle, bipartisan collaboration, and seriousness of thought.

I have more to say about this - some of it no doubt will be mistaken - but for now I'll wrap up this piece with a rough outline of what I propose to my students as a way to begin to solve wicked problems in environmental policy. Here it is:

1) First, identify the community of stakeholders.

a. Do so for their perspectives, for their interests, and for their tools.

b. Ask: Who are the stakeholders?

i. Go beyond the financial stakeholders or stockholders.

ii. Include everyone who affects, or is affected by, the policy under consideration.

c. Remember Charles Peirce’s idea: science is the work of a community, not of an individual.

d. Make concept maps, and use other kinds of visualizations of the problems.

i. This is a way of utilizing a broad range of tools. Don’t just use the tools others tell you are relevant; include the arts and the sciences alike.

ii. Drawing and sketching pictures will help you to see better. As Louis Agassiz said, “the pencil is one of the best eyes.” It is often better than a camera.

iii. Music, literature, poetry, and the visual arts may be just as helpful as the tools offered by STEM fields and policy-making professions like law.

iv. If you include the arts, you wind up including the artists; similarly, if you exclude the arts, you exclude the wisdom and insight of the artists.

v. Include ordinary daily practices. Learn to fish, even if you don’t plan to fish. Hike in the woods, even if you don’t like the outdoors. These are, in a way, practices of paying attention to the world.

e. Include other voices and texts in the conversation, not just the shareholders, but all the stakeholders.

f. Define “stakeholders” as broadly as you can. Include a community across generations. Include the departed and the not-yet-born if possible.

i. Traditions might be full of wisdom, so don’t ignore them, especially if they are specific to a place. Traditions may be inarticulate wisdom that is tested by time.

ii. Plan for seven generations. I sometimes think of this as the difference between planting those crops you will harvest this year and planting hardwood trees so that they will be old-growth trees long after you are dead. Humans – and other species – need both kinds of plants.

a. Do so for their perspectives, for their interests, and for their tools.

b. Ask: Who are the stakeholders?

i. Go beyond the financial stakeholders or stockholders.

ii. Include everyone who affects, or is affected by, the policy under consideration.

c. Remember Charles Peirce’s idea: science is the work of a community, not of an individual.

d. Make concept maps, and use other kinds of visualizations of the problems.

i. This is a way of utilizing a broad range of tools. Don’t just use the tools others tell you are relevant; include the arts and the sciences alike.

ii. Drawing and sketching pictures will help you to see better. As Louis Agassiz said, “the pencil is one of the best eyes.” It is often better than a camera.

iii. Music, literature, poetry, and the visual arts may be just as helpful as the tools offered by STEM fields and policy-making professions like law.

iv. If you include the arts, you wind up including the artists; similarly, if you exclude the arts, you exclude the wisdom and insight of the artists.

v. Include ordinary daily practices. Learn to fish, even if you don’t plan to fish. Hike in the woods, even if you don’t like the outdoors. These are, in a way, practices of paying attention to the world.

e. Include other voices and texts in the conversation, not just the shareholders, but all the stakeholders.

f. Define “stakeholders” as broadly as you can. Include a community across generations. Include the departed and the not-yet-born if possible.

i. Traditions might be full of wisdom, so don’t ignore them, especially if they are specific to a place. Traditions may be inarticulate wisdom that is tested by time.

ii. Plan for seven generations. I sometimes think of this as the difference between planting those crops you will harvest this year and planting hardwood trees so that they will be old-growth trees long after you are dead. Humans – and other species – need both kinds of plants.

|

| Bear scat along a salmon river, Katmai Preserve, Alaska |

2) Second, fill your toolbox—and your community’s toolbox—with bear poop. This is an inside reference my students will understand by the end of the semester, but I'll fill you in briefly: I take the time when I am in the wild to look at animal scat, because it is often a picture of what food is available to the animals, and that, in turn, is a picture of the problems the environment is facing. Paying attention to scat over time gives you a long-term picture of changes to the environment. Poop is a tool that is free, that is right in front of you, and that is easy to overlook as unimportant or distasteful. Bear poop that is full of salmon bones tells me one story; bear poop that is full of berries tells me another. I don't literally fill my toolbox with bear poop, but paying attention to negligible things like bear poop gives me new tools I wouldn't have otherwise. What does this mean for us?

a. Identify the community’s tools, perspectives, and skills, and seek to integrate them into a tool-wielding community.

b. See the problem as broadly as you can. We tend to frame problems based on our perspective, so do what you can to gain the perspectives of others.

Emerson: move your body so that your eyes see the world from a different angle.

c. Try to gain as many tools as you can

d. Value experience and first-hand knowledge

i. Go underwater – that is, look at the world in new and unfamiliar ways, from unfamiliar vantage points.

ii. Travel – get to know the world differently, and get to know how others know the world. Don't just do tourism, but saunter, as Thoreau puts it.

iii. Learn the languages you can – even a little bit will make a difference. Words are tools, and they are lenses through which to see the world anew.

iv. Study “unnecessary” knowledge, and not just the knowledge others tell you is necessary – don’t let others tell you what tools are worth gaining.

v. Foster your curiosity. Don’t let it die of neglect.

e. Engage in labs, even in the Humanities – learn experientially.

3) Third, have what Peirce calls “regulative ideals”

3) Third, have what Peirce calls “regulative ideals”

a. Aim high, and have a direction. But

b. Recognize that the direction will change; this is like taking bearings while navigating. You have to keep adjusting as you move and as you discover the landscape

4) Fourth, don’t expect perfection

4) Fourth, don’t expect perfection

a. and don’t expect ultimate solutions. Expect that truly ‘wicked’ problems will continue to be problems, and that they will continue to change and to spawn new problems. Such is life.

b. Instead, expect meliorism, growth, improvement

c. Peirce uses some odd words to describe all this: tychism, synechism, agapism: chance, continuity, love. Someday, look these up, or ask me to define them for you. Vocabulary is a powerful tool.

5) Fifth, do expect growth, and strive to cultivate good things. This is the work of ethics.

6) Sixth, do expect to be part of a community that continues to work on the problems for a long time.

7) And seventh, don’t give up!

5) Fifth, do expect growth, and strive to cultivate good things. This is the work of ethics.

6) Sixth, do expect to be part of a community that continues to work on the problems for a long time.

7) And seventh, don’t give up!

Of course it is possible to solve environmental policy problems apart from a community; once you’re no longer a part of a community, “policy” takes on a simpler meaning, and so does “environmental.” But merely redefining words—or merely divorcing yourself from a situation—doesn’t solve the problem. Rather, those decisions only blind us to the problem. This is satisfying our own irritation rather than satisfying the needs generated by the actual problem.

*****

[1] Mary Astell, A Serious Proposal to the Ladies, Sharon L. Jansen, ed. (Steilacoom, WA: Saltar's Point Press, 2014) p.65.

∞

The Slow, Important Work Of Poetry

At the time it seemed like chance that brought me to minor in comparative poetry in college.

Without having a master plan, over four years I wound up taking a number of poetry classes in four languages. Eventually I asked my college to consider them a new minor area of study. They agreed, and I graduated.

And then, slowly, over a quarter century, I began reading more poetry in more languages. It's always slow; I can't pick up a book of poems and read it like a novel. If the poetry is any good at all, I can read one or two poems, and then I've got to put the book down and let the words sit with me.

Often, I go back and read the same poem again, and again.

The very best poems I try to memorize, even though my memory for verse has never been good. I imagine most people would consider that a useless exercise, a waste of storage space in an already cluttered brain.

But in each season of my life I've found that it is some form of poetry that acts as salve to my soul's wounds or food that sustains its long journey forward. Homer's long story-poems; old epics and sagas from Ireland and Wales and Iceland; Vedic verses and Greek scriptures; Gregorian chants that have echoed in stone chambers for centuries; Shakespeare's or Petrarch's sonnets; the Psalms and proverbs of Hebrew priests and kings; a few words put together well by Dylan Thomas, Gary Snyder, Tomas Tranströmer, or C.S. Lewis; or the timely phrases of some of my favorite contemporaries like Patrick Hicks, Abigail Carroll, Mary Karr, Wendell Berry, Melissa Kwasny, John Lane, or Brian Turner. Each of them has, at some point, given me the daily bread I craved.

I can't seem to predict when the need will arise, but suddenly, there it is, and I find myself quoting Joachim du Bellay's sonnet about travel, and home:

That sonnet often reminds me, in turn, of verses about Abraham.

I am no good at praying, but I often wish I were. I think the fact that we make light of prayer - both by mocking those who pray and by being those who speak piously of prayer but who do not allow ourselves to confess the weakness prayer implies - says something of another shared longing, not unlike the longing for home. We long to comfort those far away when tragic events fall on them. They may be total strangers, but we know how horrible we would feel in their place, and we know that right now there is nothing we can do to staunch the flow of pain for them. But we can hold them in the center of our consciousness and, for a little while, not let any lesser thoughts crowd them out of our hearts and minds. We can, for a little while, consider our lives to be connected to theirs. We can, for a little while, ask ourselves what we might do to change the world so that this pain will not be inflicted on others.

Since I am not adept at praying, In those times I find the prayers of others buoy me up above the waves of emotional tempest. The prayer books of my tradition - the various versions of The Book of Common Prayer - often transform my anguish into something articulate. Of course, we turn to that same book when a baby is born, when a couple is wed, and when our beloved are interred. These events? We know they are coming, and yet it is not easy to prepare oneself, to be always ready for those days. I live in a tent; poetry often gives me a foundation to build on, and the better I've memorized it, the stronger that foundation becomes.

Those words, buried like seeds, slowly come to bear fruit in my life. Sometimes I wonder: was it really chance that brought me to the poems?

In the hardest of times, and also in the most joyful times, the words of poets are like a cup of water in a dry place. They refresh me, and they clear my throat so that I can take in that which sustains my own life, and speak other words, both old and new, that may sustain the lives of others.

Without having a master plan, over four years I wound up taking a number of poetry classes in four languages. Eventually I asked my college to consider them a new minor area of study. They agreed, and I graduated.

And then, slowly, over a quarter century, I began reading more poetry in more languages. It's always slow; I can't pick up a book of poems and read it like a novel. If the poetry is any good at all, I can read one or two poems, and then I've got to put the book down and let the words sit with me.

Often, I go back and read the same poem again, and again.

The very best poems I try to memorize, even though my memory for verse has never been good. I imagine most people would consider that a useless exercise, a waste of storage space in an already cluttered brain.

But in each season of my life I've found that it is some form of poetry that acts as salve to my soul's wounds or food that sustains its long journey forward. Homer's long story-poems; old epics and sagas from Ireland and Wales and Iceland; Vedic verses and Greek scriptures; Gregorian chants that have echoed in stone chambers for centuries; Shakespeare's or Petrarch's sonnets; the Psalms and proverbs of Hebrew priests and kings; a few words put together well by Dylan Thomas, Gary Snyder, Tomas Tranströmer, or C.S. Lewis; or the timely phrases of some of my favorite contemporaries like Patrick Hicks, Abigail Carroll, Mary Karr, Wendell Berry, Melissa Kwasny, John Lane, or Brian Turner. Each of them has, at some point, given me the daily bread I craved.

I can't seem to predict when the need will arise, but suddenly, there it is, and I find myself quoting Joachim du Bellay's sonnet about travel, and home:

Heureux qui, comme Ulysse, a fait un beau voyage

Ou comme cestuy-là qui conquit la toison

Et puis est retourné, plein d'usage et raison

Vivre entre ses parents le reste de son âgeHis simple words save me from forming new ones and free me to think and feel as the occasion demands; his words give utterance to what I find welling up inside me. His words change my homesickness into a stage in a worthwhile journey. Here is a very loose translation of those lines: "Happy is he who, like Ulysses, made a beautiful journey, or like that man who seized the Golden Fleece, and then traveled home again, full of wisdom, to live the rest of his life with his family." We are pulled in both directions at once: towards the Golden Fleece and adventures in Troy, and towards the home we left behind when we departed on our quest.

That sonnet often reminds me, in turn, of verses about Abraham.

Consider Abraham, who dwelled in tents,

because he was looking forward to a city with foundations.This longing for home that I sometimes have when I travel is itself no alien in any land. We all may feel it in any place. Everyone feels lost sometimes. Knowing that others have found words to express their feeling of being lost is itself a reminder that we are not alone. Hölderlin's opening words in his poem about St. John's exile on Patmos say this well:

Nah ist, und schwer zu fassen, der GottIt does seem that God - like home and family and love and neighbors - is close enough to grasp, so close that we could meaningfully touch them all right now. And yet so far that nothing but our words can draw near.

I am no good at praying, but I often wish I were. I think the fact that we make light of prayer - both by mocking those who pray and by being those who speak piously of prayer but who do not allow ourselves to confess the weakness prayer implies - says something of another shared longing, not unlike the longing for home. We long to comfort those far away when tragic events fall on them. They may be total strangers, but we know how horrible we would feel in their place, and we know that right now there is nothing we can do to staunch the flow of pain for them. But we can hold them in the center of our consciousness and, for a little while, not let any lesser thoughts crowd them out of our hearts and minds. We can, for a little while, consider our lives to be connected to theirs. We can, for a little while, ask ourselves what we might do to change the world so that this pain will not be inflicted on others.

Since I am not adept at praying, In those times I find the prayers of others buoy me up above the waves of emotional tempest. The prayer books of my tradition - the various versions of The Book of Common Prayer - often transform my anguish into something articulate. Of course, we turn to that same book when a baby is born, when a couple is wed, and when our beloved are interred. These events? We know they are coming, and yet it is not easy to prepare oneself, to be always ready for those days. I live in a tent; poetry often gives me a foundation to build on, and the better I've memorized it, the stronger that foundation becomes.

Those words, buried like seeds, slowly come to bear fruit in my life. Sometimes I wonder: was it really chance that brought me to the poems?

In the hardest of times, and also in the most joyful times, the words of poets are like a cup of water in a dry place. They refresh me, and they clear my throat so that I can take in that which sustains my own life, and speak other words, both old and new, that may sustain the lives of others.

∞

Wendell Berry: Past A Certain Scale, There Is No Dissent From Technological Choice

“But past a certain scale, as C.S. Lewis wrote, the person who makes a technological choice does not choose for himself alone, but for others; past a certain scale he chooses for all others. If the effects are lasting enough, he chooses for the future. He makes, then, a choice that can neither be chosen against nor unchosen. Past a certain scale, there is no dissent from technological choice.”

-- Wendell Berry, “A Promise Made In Love, Awe, And Fear,” in Moral Ground: Ethical Action For A Planet In Peril. Kathleen Dean Moore and Michael P. Nelson, eds. (San Antonio: Trinity University Press, 2010) p. 388.