Wild Four O’Clock (Mirabilis nyctaginea)

A quick sketch while having coffee with a colleague in a campus garden today.

The last generation of monarch butterflies is passing through. My garden is full of them feasting on late summer blossoms, and perching in the trees overnight. Here’s a quick morning watercolor of one I saw yesterday. Wish it well on its long journey.

Ten More Years

Ten years ago today an accident nearly killed me.

This morning I’m reflecting on a how grateful I am for a supportive community, co-workers who stepped up to carry my workload, friends far and near who offered prayers and words of encouragement,and especially my family, who put up with me during a long and slow recovery. My wife is a saint.

Of course today is just another day. But it’s also a milestone, a marker along the road, reminding me how far I have come. And reminding me I have not walked this road alone.

My first two grandchildren were born this year. Both of them have fallen asleep in my arms several times. What a gift it is to meet them, to be alive to see them come into this world.

I’m grateful for the thousand kindnesses, and for ten years to begin to pay them forward to others who need similar care.

Vanessa cardui (painted lady) butterfly in my garden when I got home today.

Agapostemon bee on Aster flowers in the campus prairie restoration garden this morning.

Prairie seeds

Walked some ditches in an especially rural part of our very rural state last week, and filled my field coat pocket with seeds from native grasses and flowers. Looking forward to seeing what comes of those seeds in the gardens where I will scatter them. At least a dozen species came into view: liatris, prairie clover, small bluestem, and so many others. The prairie knows how to gladden a heart in late summer.

African Philosophies

Two recent book purchases. Curiosity and wonder are not limited by geography. Philosophy springs up wherever minds are moved by wonder.

My teaching career began with ancient Mediterranean philosophy and American (U.S.) philosophy. In grad school I mentioned that to a German philosopher who laughed at me and said there was no philosophy in America.

It would have been more correct to say that he was not curious enough to ask what philosophy had rooted in the soil of this continent.

Over the decades of my university career I’ve enjoyed teaching Ancient Greek thought and American Transcendentalist and Pragmatist philosophies, but I’ve also loved developing new courses in the other philosophies of the Americas, and in classical philosophies of India, China, Japan, and beyond.

In recent years some colleagues and I have been reading all the African philosophers we can find. Naturally, we often run into problems of translation. But that makes every new book we can read a newfound treasure. The ideas are often old and deeply rooted, but new to my eyes. And what is new to me sparks wonder, curiosity, and new appreciation and admiration.

Pictured: Africana Philosophy by Peter Adamson and Chile Jeffers (Oxford University Press, 2025) and An African History of Africa, by Zeinab Badawi (Mariner Books, 2024) 📚🌍

College Weekend

Arrived at my office to find that one of my students had dropped off a copy of their handwritten notes. Friday’s class on the pre-Socratic philosophers and the origins of physics appears to have led to a weekend of deep thinking.

The notes are about matter, the concept of the void, the nature of mind, our place in the universe, and our responsibilities.

This is a great way to start the day.

Invertebrate Neighbors

J.B.S. Haldane famously quipped that if he learned anything about religion from his biological studies, it was that “God has an inordinate fondness for beetles.”

Yesterday I was thinking something similar about mollusks. They’re in the deep ocean and in my kitchen garden. Snails live in salt water, fresh water, and on the trees here on the prairie. Mollusks are everywhere, it seems.

When we encounter them we often flinch at their boneless, wet bodies.

Alternatively, when I say I study freshwater mussels, the first question many people ask me is “Can you eat them?”

We ecologists often speak more loftily of the “ecosystem services” that other species provide. Mollusks filter water, feed other species, and decompose other organisms.

It is a challenge to value our neighbors beyond the ways we can profit from their existence.

It’s a challenge, but I believe we are up to the challenge, and I think that if we try, we will find that rising to the challenge is good for all of us—and for our neighbors. 🐌🐚🦪

Life is more than employment

When we make education about employment, we neglect all the parts of life that are not employment.

Life is more than employment.

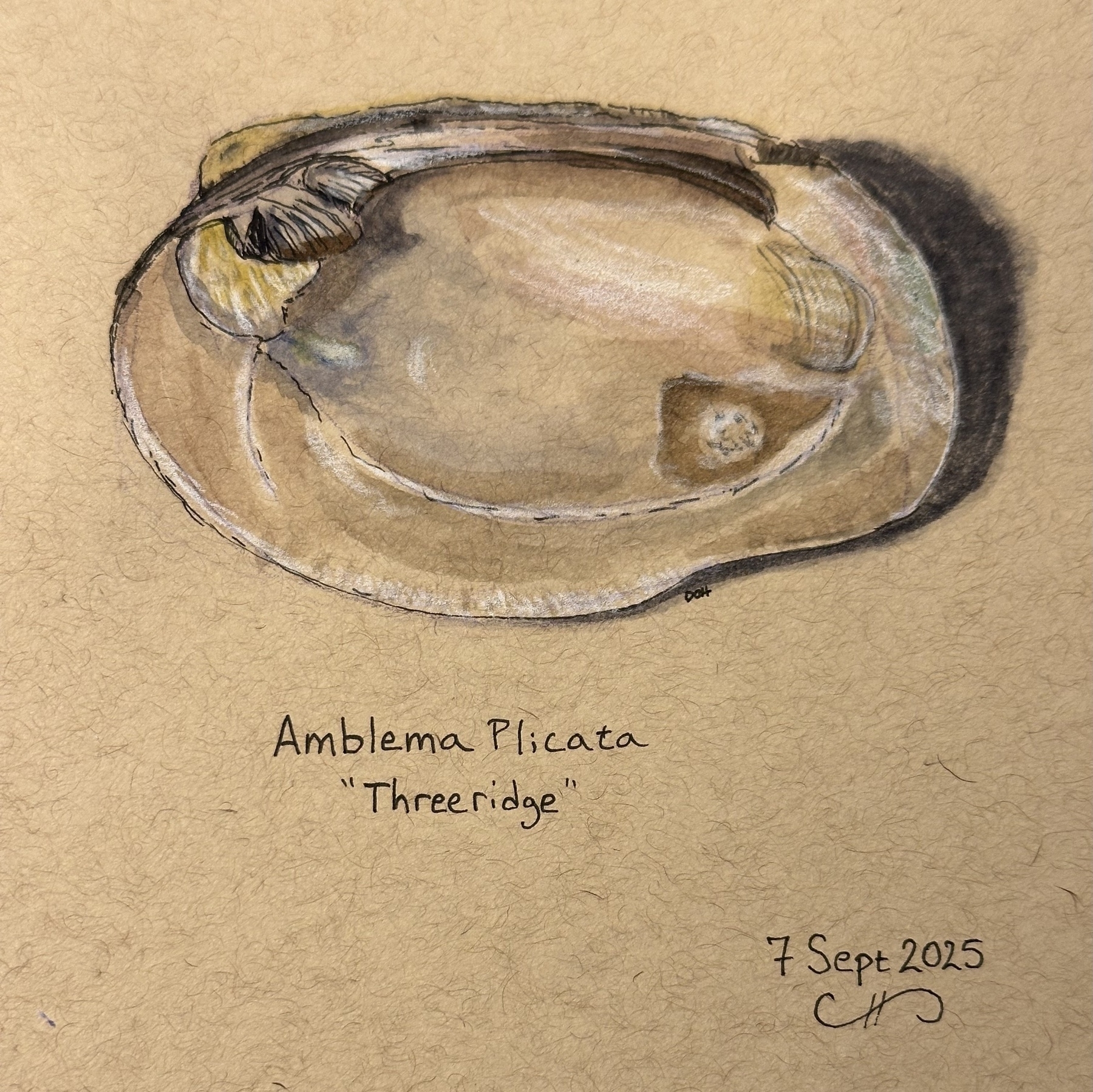

Threeridge mussel, interior view

Interior view of the same shell as the previous sketch.

Last year I completed the Freshwater Mussel Workshop at the Museum of Biological Diversity at The Ohio State University. It was a great workshop that included lectures by experts, lots of time with specimens in the museum, and fieldwork in several nearby rivers.

There are a lot of species of mussels in North America, though, and many look alike to novices like me.

Much of my work in sketching mussels is about identification and gaining familiarity with each species.

I spend time on the river each week (don’t try this at home without appropriate permits, which I have) but sometimes I have to make a best guess when recording species I observe in my notebook. Later, sketching from photos and looking at my field measurements, I can usually make a more accurate determination of species. 🐚🦪🎨

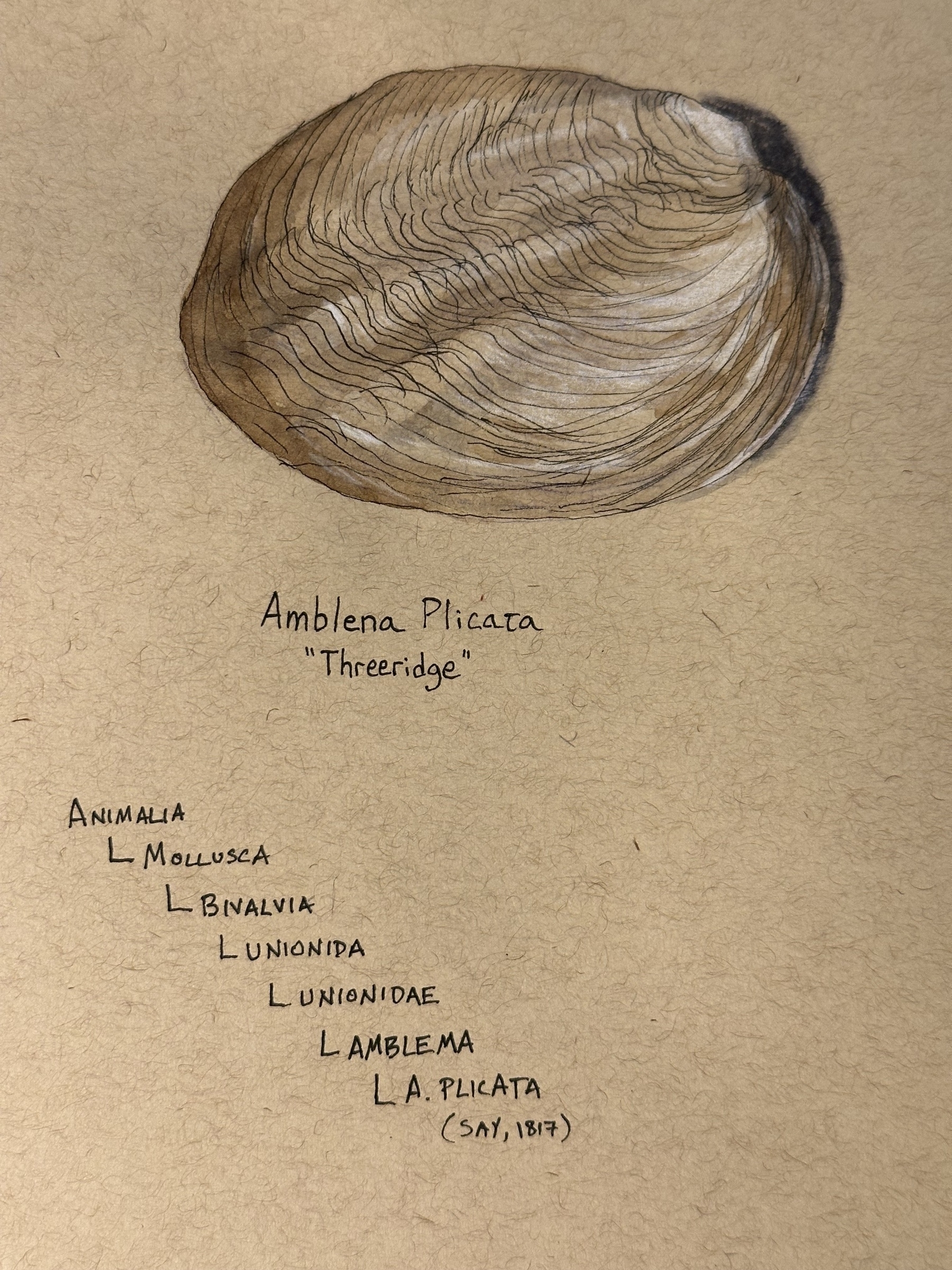

Threeridge Mussel

Morning sketch: Amblema Plicata, one of the common mussels in the Midwest.

There are about 300 species of mussels native to the freshwaters of North America. They used to keep rivers clear and clean, until we started harvesting them for shirt buttons and pearls.

We harvested so quickly and recklessly most haven’t been able to recover.

We thought their abundance meant they would always be available.

But it turns out their abundance was partly due to longevity, and partly due to a healthy relationship with host fishes, and with healthy terrestrial plant communities that kept soil out of the water. And a number of other factors that we changed without understanding the long-term downstream effects.

A reminder that we all live downstream. 🦪🐚🎨

Late Summer Blossoms

Fireworks in my garden.

Native prairie plants in my garden. Autumn is coming soon, but the blossoms continue to appear for now.

Why such beautiful flowers? I plant them for all my neighbors, including many pollinators.

But I choose them especially for my wife, who deserves all this and much more besides.

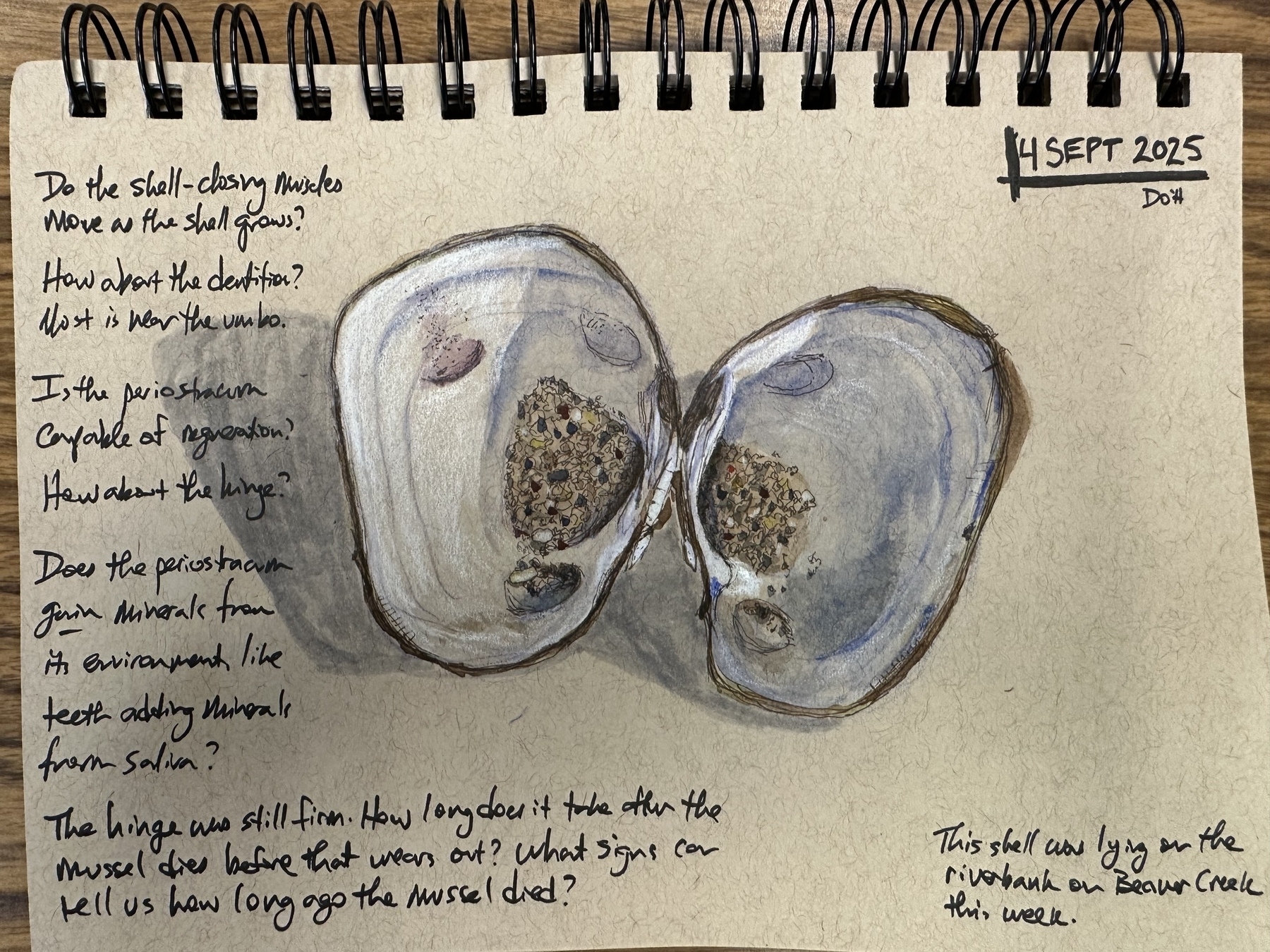

Mussel Sketch

Sketching at my desk this morning, from a photo I took while looking for mussels in a nearby tributary to the Big Sioux River.

As always, the sketching helps me see more clearly, and it raises questions for me.

I’ve been looking for populations of live mussels and, lamentably, haven’t been finding any. I know they’re in there, but the population is sparse and spread out. Hoping to find some thriving populations soon. 🐚🦪🎨

Bumble Flower Beetles (Eurphoria Inda) on my Cup Plant (Silphium Perfoliatum). The plant is ten feet tall, and has hundreds of blossoms. These two were tussling over this one blossom like two kids in a big back seat shoving their sibling because they crossed the line.

Fishing

Yesterday a student asked me to supervise her honors project. She has learned fly-fishing and wants to help people who might not otherwise have access to the outdoors and clean water learn fly-fishing as well.

She came to me because I am Director of Environmental Studies at our uni.

But she did not know that I was a fly-fishing guide in grad school in New Mexico, that I have written a book about brook trout, fly-fishing, and ecology, and that I teach courses about salmonids in Alaska.

Her face looked like she had just stumbled on a hidden treasure.

I gave her a copy of my book and agreed to advise her project. 🐟

What a delight it is to be thankful for the little things.

This is so easy for me to forget, but when I remember and pause to consider the world with gratitude, even for a moment, it’s like the lights coming on in a dark room.

American Rubyspot (Hetaerina Americana, male) damselfly. Sept 1, 2025. Beaver Creek Nature Area, South Dakota.

I told my Environmental Philosophy students we would be meeting outdoors all semester, except when tornadoes or lightning occur.

Watch this space for updates on how that is going here on the prairie.

One of the many things I’d like to do today if today were infinitely long is to write a paper about the usefulness of Peirce’s semiotics to developing a better A.I.

But I am off to teach, and to work in the gardens.

These are both good paths to follow.