Eighty years since the end of WWII, and the older I get the more I realize how little I understand about how it started.

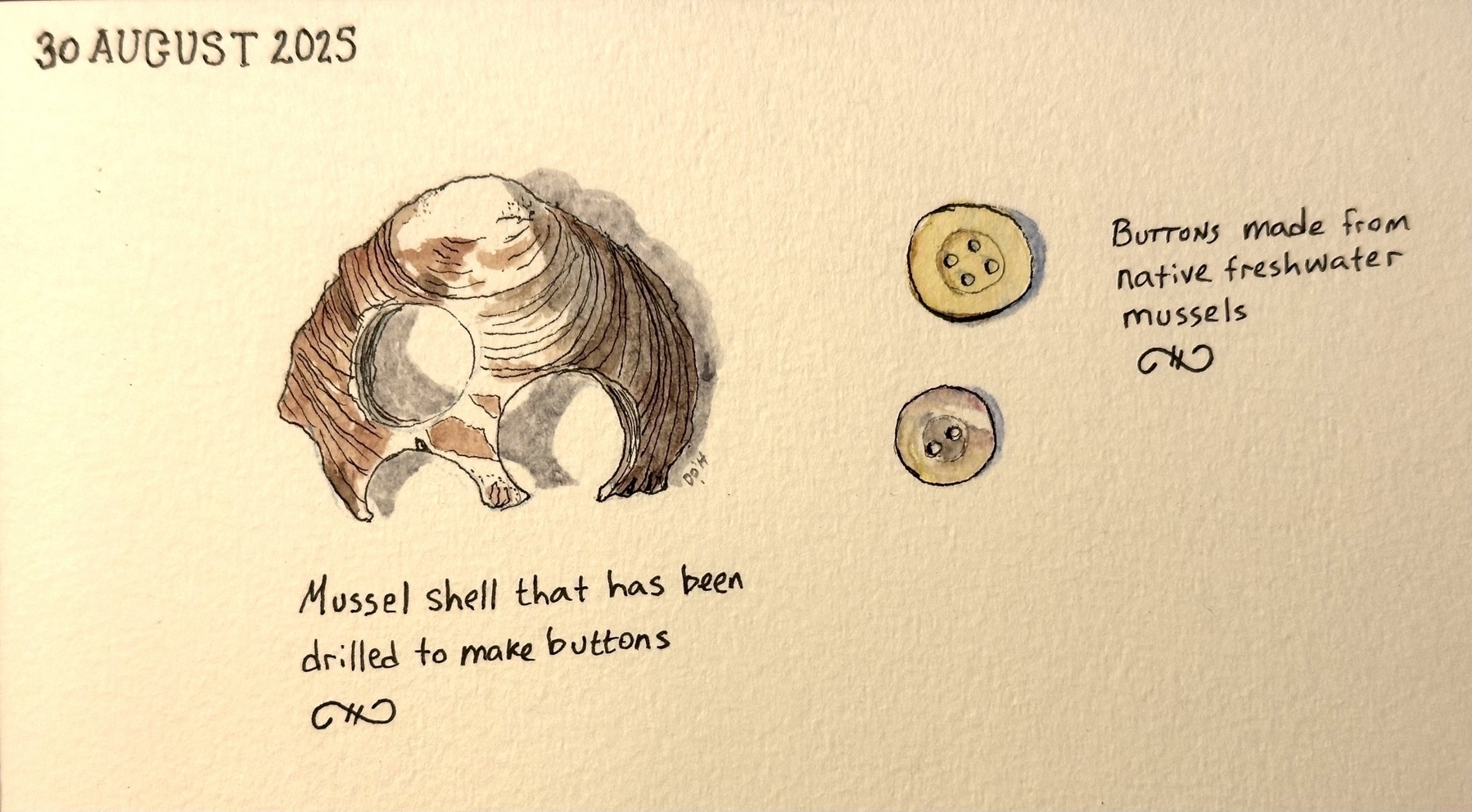

Mussels and Shirt Buttons

Morning sketch: a freshwater mussel shell that was drilled to make shirt buttons, and a few buttons made from mussel shells.

For several decades in the late 1800s and early 1900s we hauled out thousands of tons of freshwater mussels (Unionidae species, mostly) from our rivers, especially in the Midwest. Today drilled shells can still be found along the banks of many of our rivers.

Buttons like these can easily be found in rural flea markets where jars of buttons from old farmsteads are for sale. When a shirt wore out on a farm, the cloth was repurposed and the buttons were saved for making new clothes.

We thought the mussels were a limitless resource because they no were so abundant. Roughly 300 species of freshwater mussels are native to the waters of the United States.

We didn’t realize that those mussels grow slowly, or that their life cycles could be so easily disrupted by our industrial practices.

We also didn’t know that a single mussel could filter 25 gallons (100 liters) of water each day.

Some species quickly went extinct or were extirpated. Most others have been put at various stages of risk of extinction or population collapse.

But remnant populations are still to be found throughout the U.S., and I am hopeful that many of them can be restored if we are intentional and careful.

One of my hopes is to see their populations increase in my river here in eastern South Dakota. 🐚🦪🎨

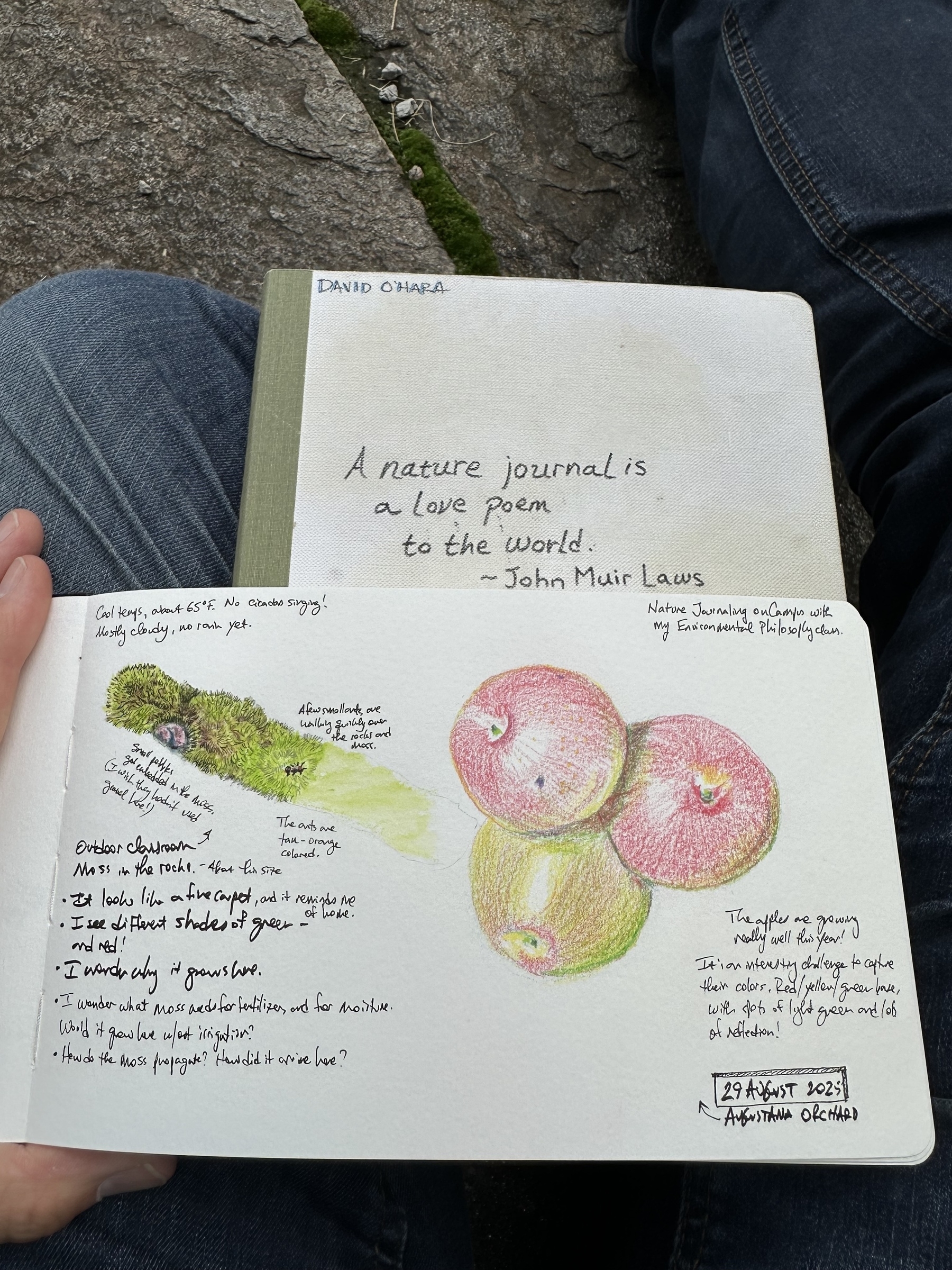

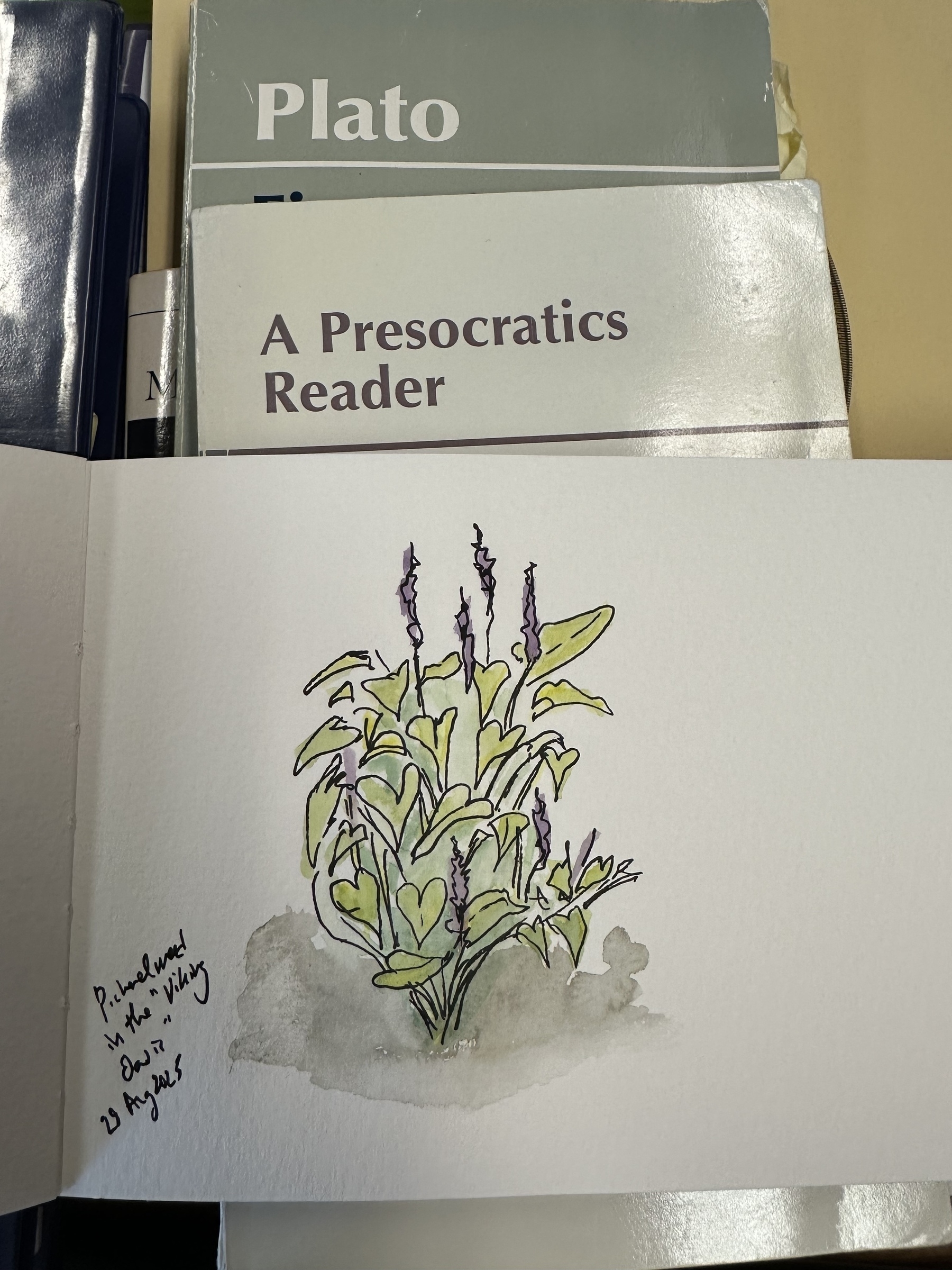

Environmental Philosophy Nature Journaling

I’m requiring my students to keep nature journals based on what they see on our campus, so I am doing the same. Here are today’s entries from my journal.

These sketches represent three locations on campus: the orchard my students and colleagues and I planted; the outdoor classroom my students and I designed and built; and the campus pond, which is used by many of us as a campus-as-living-lab teaching site.🎨

Back to School

After a yearlong sabbatical I head back to the classroom today.

This year has been a great gift, and I’m very grateful to the Bush Fellowship that allowed me to take classes, buy more books, and travel for research and study.

This week I’ve been doing what I always do before classes begin: tending the campus gardens, giving tours to alumni and emeritus faculty, attending meetings to prepare for the new semester.

And taking time in the silence of empty classrooms to walk around and lay a hand on each desk, pausing to think about students I don’t yet know. Someone will sit in this chair, at this desk. Who knows what that student needs from professors like me? What gifts do they have, what are they eager to learn? What is holding them back from doing wonderful things? How can I help? How can I get out of the way?

And at each desk I pray for that student. A quick prayer of blessing.

To teach them, and to hold them in the light for a moment before the term begins, is a blessing to me.

I don’t know how much longer I will teach here. I’m always thinking of new things I could learn, new paths of discovery and wonder to pursue.

But today, here, now, I am eager to return to the classroom, to learn the names and faces of my students, and to discover how I can help them take the next steps along their paths.

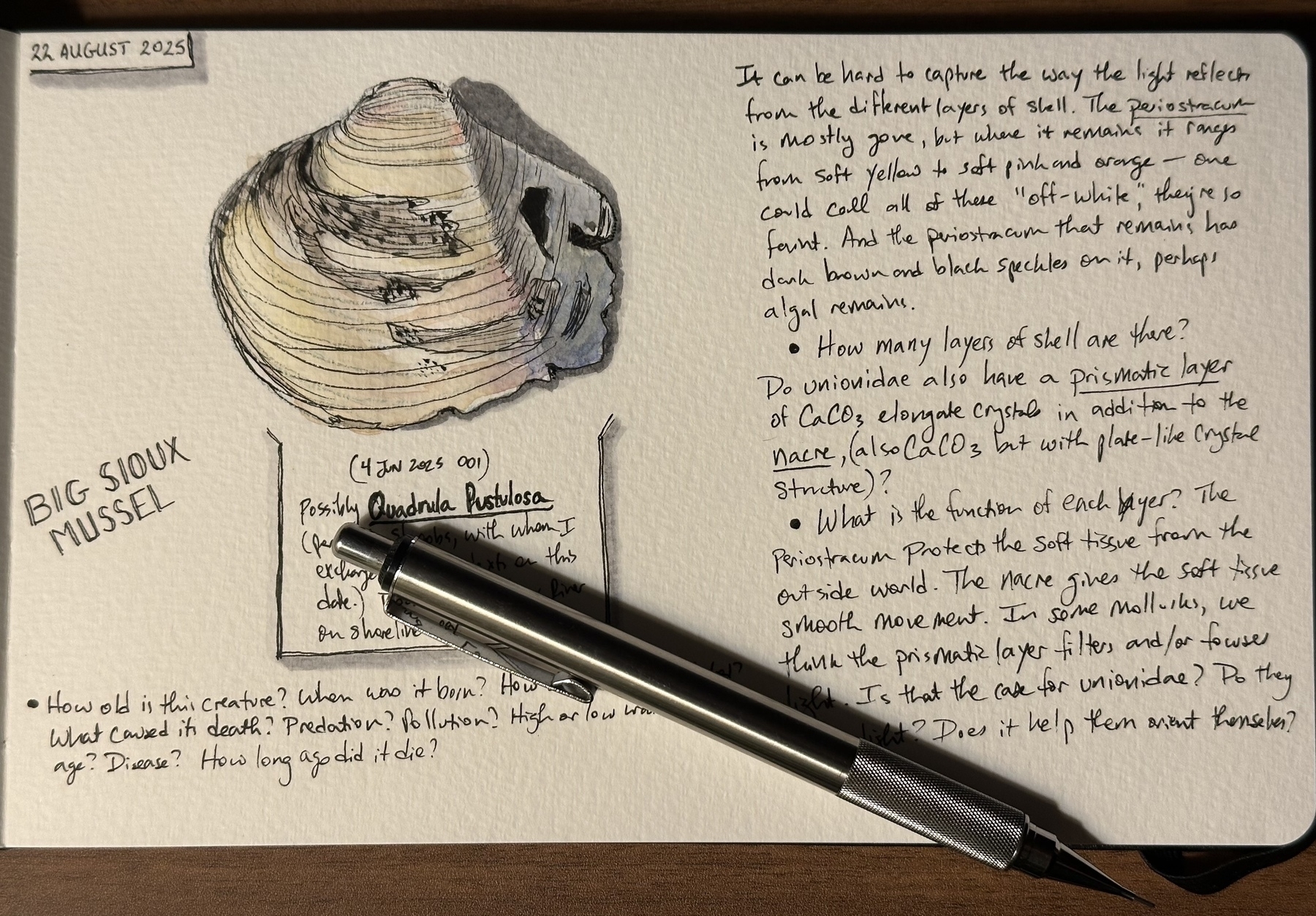

Sketching and Thinking

Morning sketch of a unionid mussel I found on the bank of the Big Sioux River earlier this year.

First the sketch, then the questions that the sketch brought to mind.

Sketching, like writing, can be a means of thinking.

🐚🦪🎨

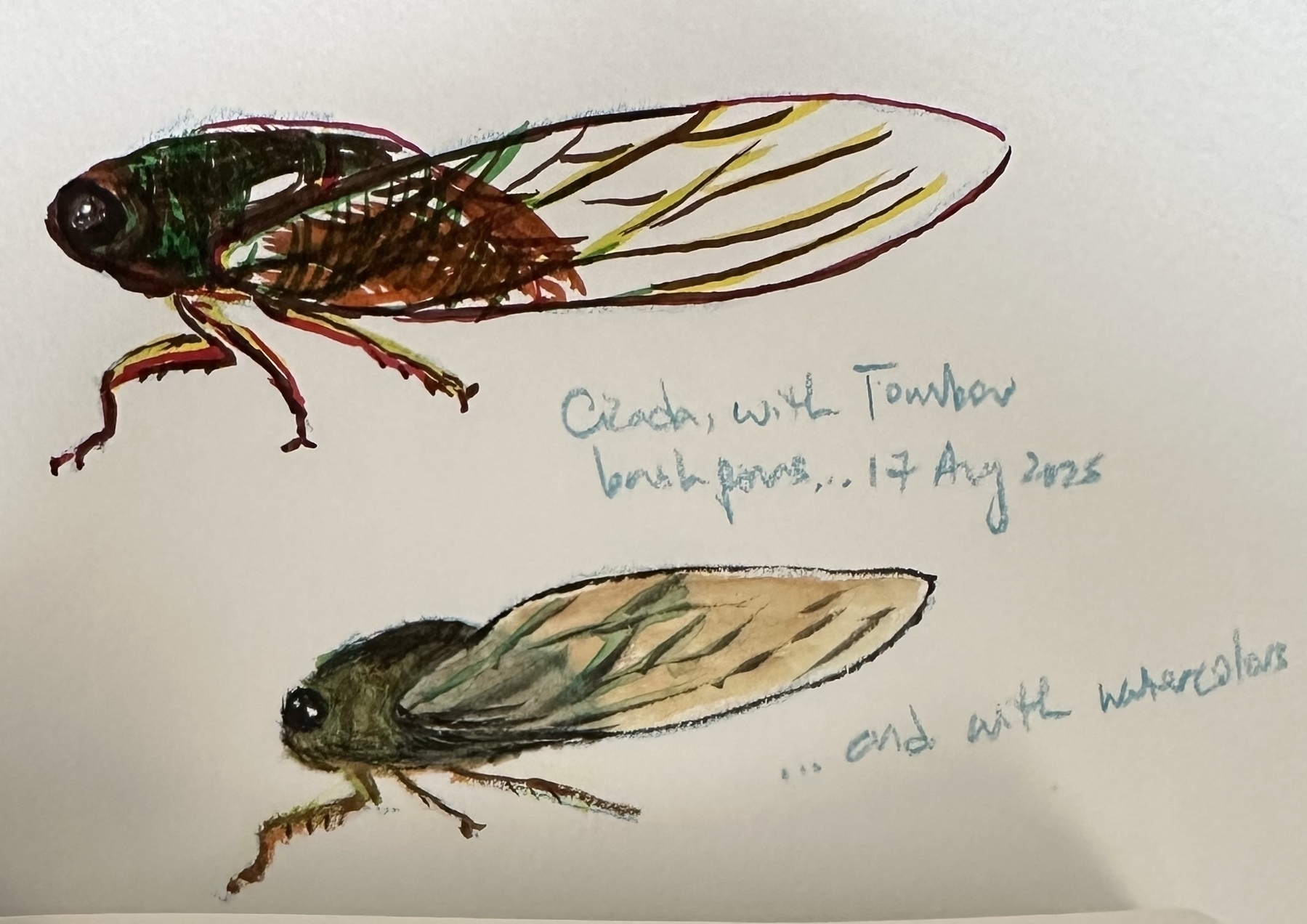

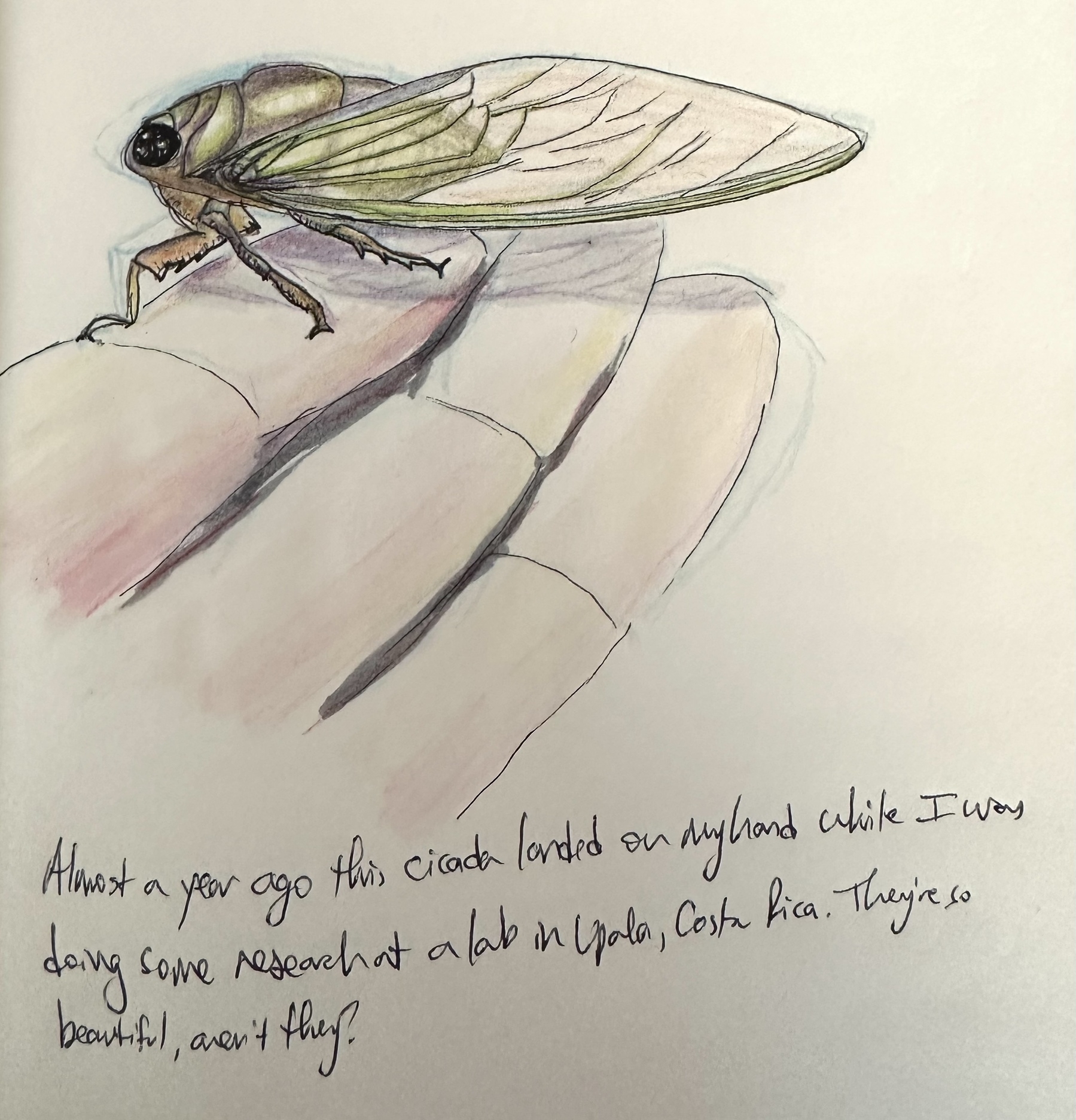

Cicadas for Claire

Drawing cicadas for my granddaughter.

As part of today’s entry in the book I’m writing for my granddaughter, I wrote about cicadas. I wanted to sketch or paint one in the book so I was experimenting with different media.

Who knew I’d have this much fun playing with art? I’m still a novice but very much enjoying it.

Learning the Bees

90% of the 20,000 or so species of bees in the world are solitary.

Most of them are not interested in stinging you.

Many of them live underground. Many others live in small holes in fallen trees or plant stems.

We tend to think bees live in social (or eusocial) hives, and that they swarm, because those are the ones we make the most intentional use of.

Bees that are solitary are important pollinators everywhere, but because we don’t make money (or get honey) from them directly, we tend not to notice them.

Some native bees in the U.S. (we have about 4000 native species) are so small that if they landed on the eye of a large bumblebee they wouldn’t cover the whole eye.

Which means they might fly past me or even land on my skin without my noticing it.

Want to learn more about bees? Here are a few quick tips:

-

Go outside and watch different sizes of flowers. Be still for a while so you don’t scare them away. Also go outside early on a cool morning in late summer to see the little ones sleeping on flowers.

-

Buy a copy of The Bees In Your Backyard. Trust me. Worth it.

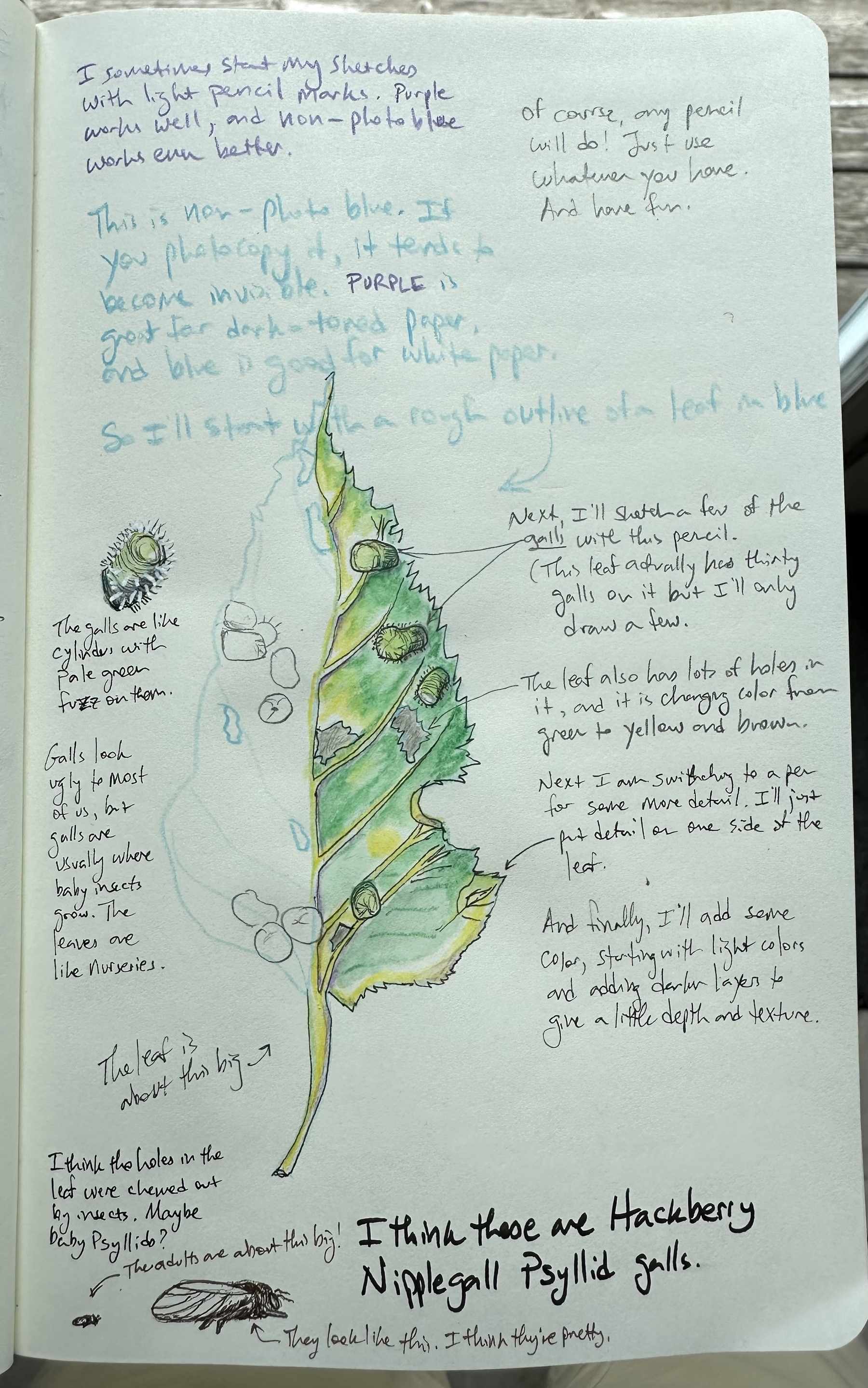

Nature Journaling for Felix

This morning I found a bunch of leaves covered with galls. Galls are interesting, and they often make me wonder who is growing inside them.

I took some quick photos, dropped the leaf, and came home to journal.

It has been a few weeks since I have written in the books I’m writing for my grandchildren, so I decided to turn today’s entry for Felix into a story about the Wild Wonder nature journaling workshop I recently attended in California, along with an illustration of what I learned.

It’s hard to know how old Felix will be when he reads this, so I’m just writing what comes to mind and hoping he will enjoy watching his grandfather continuing to learn.

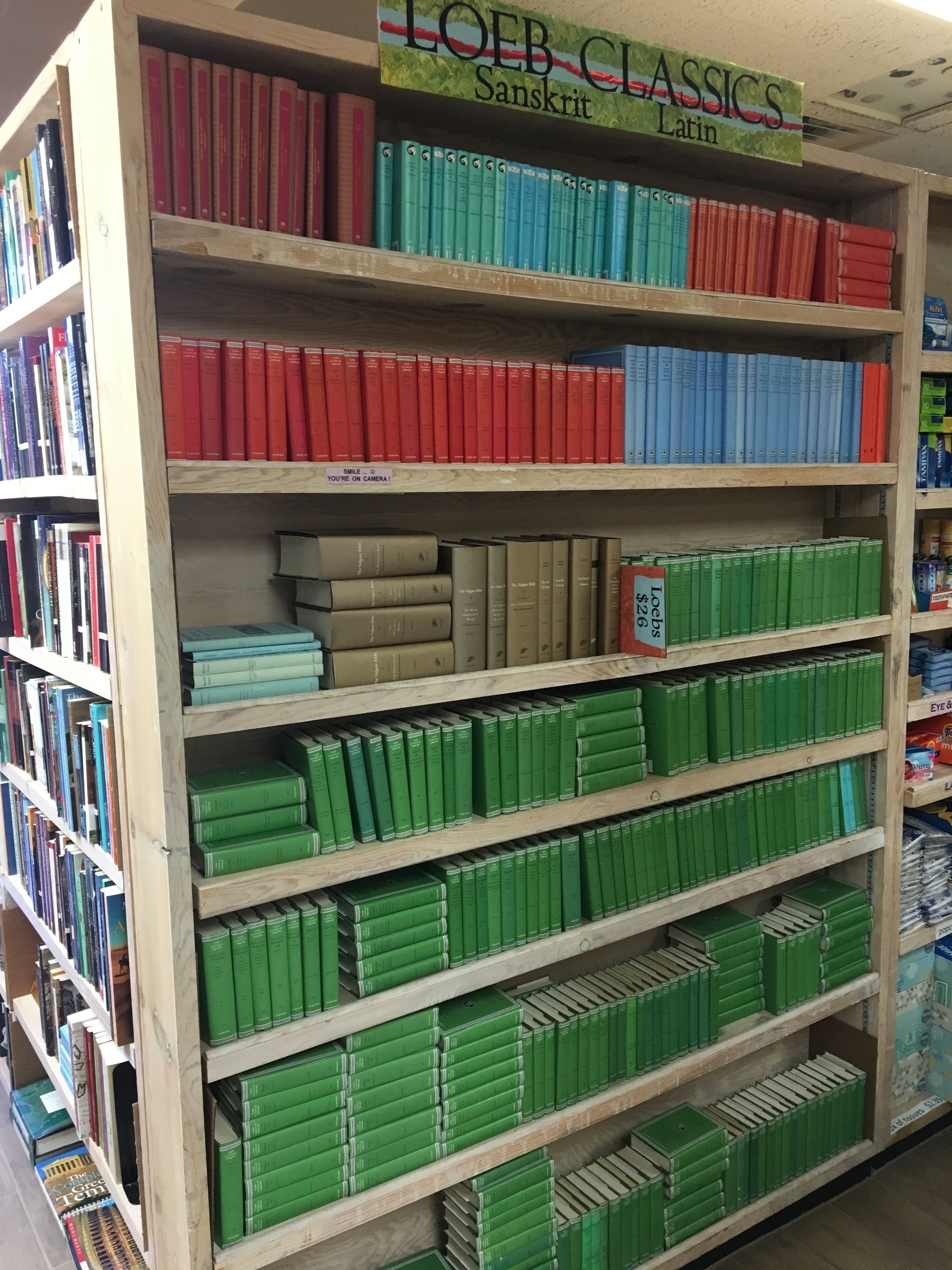

Favorite Bookstores

What’s a brick-and-mortar bookstore you rarely visit without buying something?

If you know what you’re looking for, it’s easy to find books online.

Really good bookstores often show me books that I wasn’t looking for but that I’m glad to have found.

Here are some of my favorites:

-

The Golden Notebook, (Woodstock, NY)

-

Shakespeare & Co, (Missoula, MT)

-

Zandbroz, (Sioux Falls, SD and Fargo, ND)

-

Collected Works Bookstore and Coffeehouse, (Santa Fe, NM)

-

Powell’s (Portland, OR and Chicago)

-

St John’s College bookstore, (Santa Fe, NM) (this one is amazing. Best college bookstore ever? Maybe.)

-

El Ateneo (Buenos Aires. Worth it for the location alone, but obvs also for the books)

-

Librería Desnivel, (Madrid)

-

Monroe Street Books, (Middlebury, VT)

-

The Vermont Bookstore, (Middlebury, VT) 📚

Giving away my pencils

Spent last night in Moab, so I spent this morning at Arches National Park. It wasn’t busy, so I could spend a leisurely morning walking and sketching. Even so, I felt I was moving much more slowly than most of the other visitors.

Sometimes when I stand to sketch or paint people come up and ask if they can watch. Of course! I’m happy to share the process and to talk about what I am doing and why.

Today one family asked if their little girl could see my work. I sat down in the shade (it was about 100°F) and invited them to sit with me.

I asked if she had art tools with her on her vacation and she said no. So I gave her a lesson in watercolor pencils and then gave her mine. I’ve been using them all summer so most of them were half used up anyway. She seemed happy, and so did her parents. I also gave a pencil lesson to two other kids and then gave them my last sketching pencils.

When I’ve given away my tools, that is probably a sign that it is time to head home! The fall semester is approaching, after all.

Still, my heart longs to stay in the high desert, to wander among the rocks, to sketch the dry, thin spaces, and to watch the meteors in the night sky. 🎨

On my way out of the National Forest last night I had the road to myself — to myself and the cattle and wildlife, that is. Came upon this wonderful vista just as the sun set, looking east towards Capitol Reef and Moab. Our public lands are treasures.

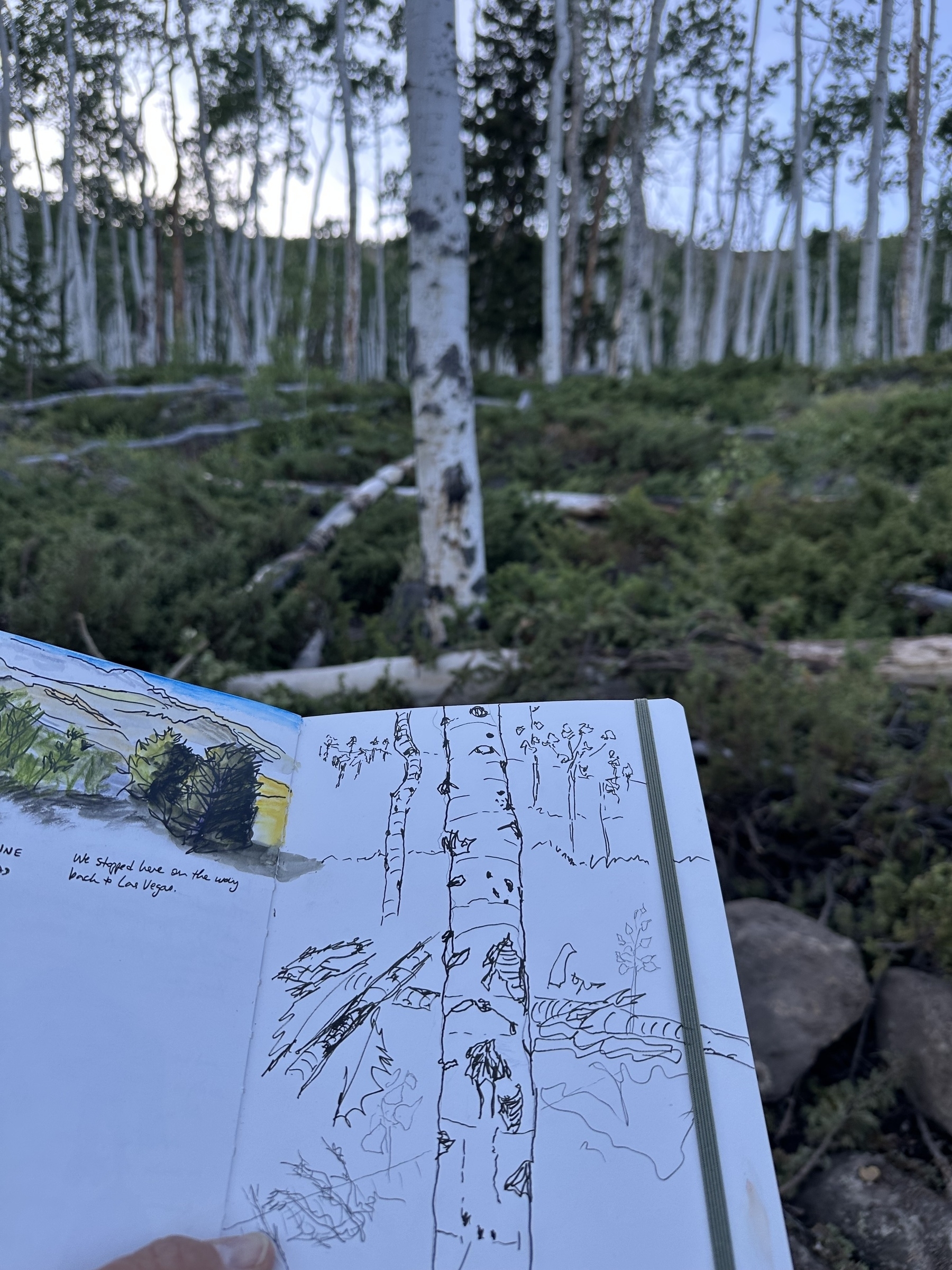

Yesterday on my drive from Las Vegas to Moab I stopped in Fishlake National Forest to see Pando, the world’s largest tree. And to spend a little time walking around the grove and sketching the tree. 🎨🌳

Wild Wonder

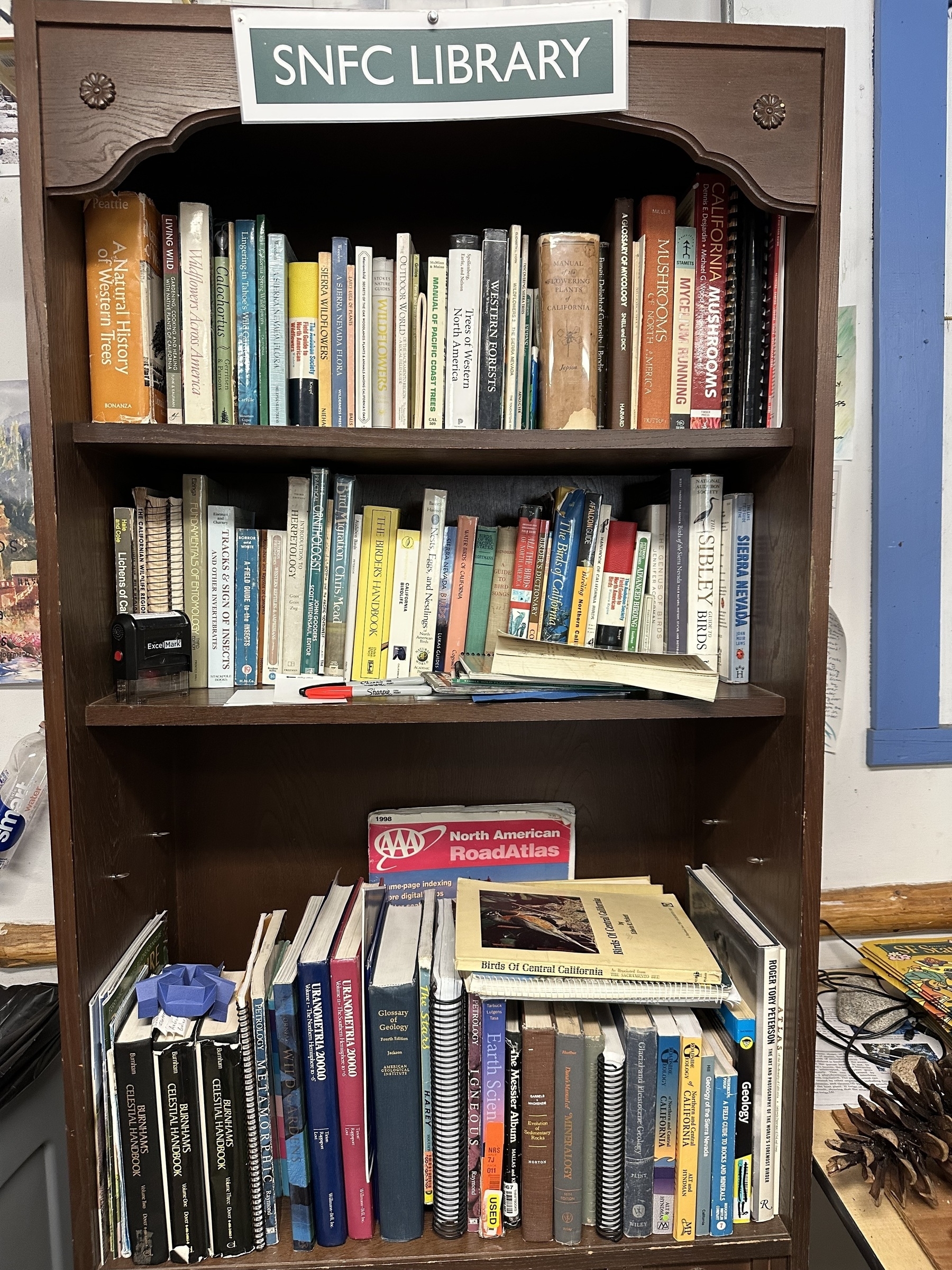

Spent the last week at a Wild Wonder nature journaling workshop in the Sierra Nevada – a last gasp of my sabbatical, and a great preparation for this fall semester’s environmental studies teaching.

Spent a week learning with John Muir Laws and Robin Lee Carlson, both of whom have taught me a lot through their books.

And I was blissfully offline, since we met at the San Francisco State University Sierra Nevada Field Campus, where there is no wifi and no cell reception.

We spent a lot of time outdoors, and some time sitting at microscopes to look at bees and other invertebrates. And when we needed information about species, habitat, etc, we did some radical stuff: we asked one another (a lot of us there had expertise to share) and we looked in books.

Now I’m catching up on email before beginning the 2000-mile drive home. I’ve got my tent and sketchbooks in my car, and I plan to stretch this out a bit, so if you email or call, you might have to wait a while for a reply.

Most likely, I’ll be sitting on a hill or by a river somewhere, sketching and journaling. Feel free to leave a message.

Here’s an unedited photo of the sunset two nights ago from Saddle Pass. The colors were stunning as the sun set on one side and the moon rose over the Sierra Buttes on the other side. We alternated between trying to capture the colors with ink and paint, and just sitting there in awe of the wild wonder before us.

Not a bad way to bring my summer to a close, and an excellent way to prepare for another year of teaching. 🎨

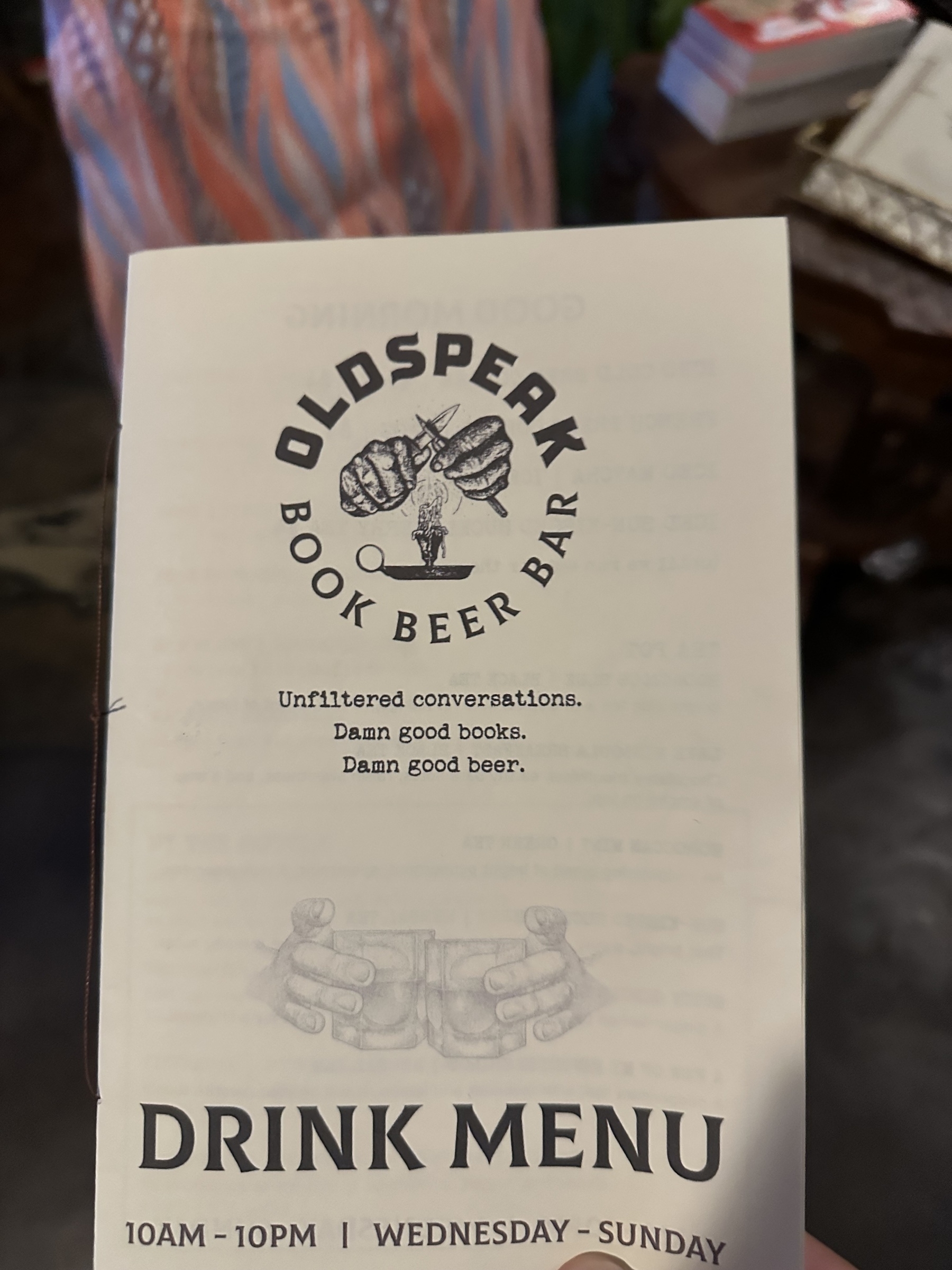

In Boise tonight, and I have two new recommendations for places to eat and drink and find books.

Visiting two alums and their newborn in Montana. Last night we babysat so the young parents could go out on a date. Feels like academic grandparenting. Which I am enjoying quite a lot.

Mato Tipila / Bear Lodge

Sabbatical Reflection

My sabbatical is coming to an end soon, but not before I take one more class. I’ll be joining a Wild Wonder workshop in California next month, learning the art of nature journaling with Robin Lee Carlson and John Muir Laws.

This sabbatical has been an immense gift. I’ve studied freshwater mussels at Ohio State University; I took an environmental writing class through Orion Magazine in upstate New York; and my wife and I dipped into our savings to take in some mutually beneficial conferences, and to visit family in New York, Chicago, and Sweden.

I am grateful for the opportunities, and I look forward to sharing what I have learned with my students.

It also has me considering: what next? Do I continue to teach as I have, or do I look for new ways to expand that teaching?

I’m not sure. For this coming year, at least, I will go back to doing what I’ve done before (see my note to my students for more about that)

But I do so with an eye on the horizon. Higher education has been a wonderful journey and a great place to work, and I don’t plan to leave altogether, but I’m wondering how else to make use of this work that I have for the benefit of my community. This is a joyful thing to ponder!

One of my practices during my sabbatical has been such pondering, in the consistent form of journaling. I’ve just about 450 handwritten pages of journal at this point, plus a bunch of sketchbooks I’ve filled, in addition to the writing I do with a keyboard. I review that writing often and find themes emerge that help me think about what lies ahead.

One thing for sure: I don’t ever want to stop learning.

Another: I don’t ever want to stop sharing what I learn with those who might benefit from it.

Bumblebee on purple prairie clover.

So often critiques of higher education complain about overpaid teachers who corrupt the youth.

I’d like to suggest walking a mile in the shoes of a public school teacher—or of a SLAC professor—before offering such critiques.

Met with some other faculty yesterday for a “shut up and write” session at a local pub. The deal: we order our drinks, then spend an hour writing in silence. Then someone calls time, we close laptops, and we talk about whatever comes to mind.

It’s productive, and it builds community. So good.