Sketches from the Omega Institute 🎨📝

A few sketches from the Orion Environmental Writers’ Workshop last week.

The workshop was held at the Omega Institute in upstate NY. I grew up only a few miles away and had heard of the place but knew nothing about it.

It was a good place for a conference, in part because I had very weak cell signal and spotty wifi. The landscape kept my attention. The pergola is at the entrance to a garden, and the sign outside it asks people not to be on their phones while in the garden.

One day my writing instructor sent us out to look for certain shapes in nature: a heart, a spiral, roots, a star, a feather. Given a little license, I could find most of that in a stump left after a tree was felled. 🎨

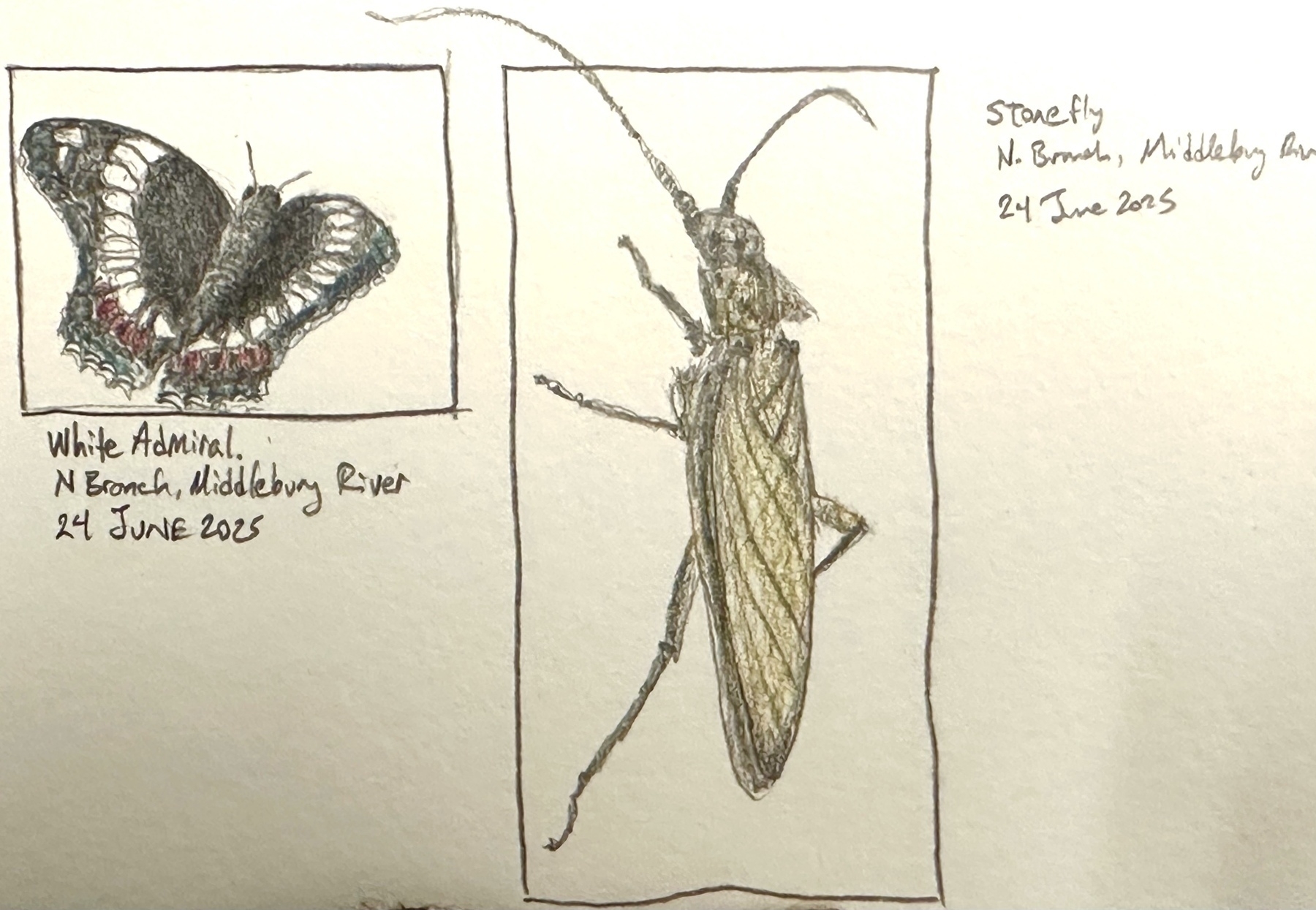

Daily Sketch 📝🎨🦋🪳

Daily sketch. Actually, this is one of several daily sketches from yesterday, since I had a lot of time on airplanes to go back over my photos from the previous week.

Flew home from Vermont last night after attending the Orion Magazine environmental writers’ workshop. The workshop was an amazingly helpful experience for me as a writer and as a teacher of writing.

Also took some time to visit family, a friend I haven’t seen since high school, and one of my frequent co-authors. He and I took a few ecology walks in a place we’ve never visited before, which prompted these sketches. As the heat wave settled over us, butterflies cycled down from the canopy to the cool reaches of the forested gorge in which we were hiking. Lots of papilio and vanessa, including this one. Also lots of riparian invertebrates were emerging, including some trichoptera, megaloptera and this plecoptera. And of course a zillion midges that wanted to explore my nostrils, ear canals, and eyes.

A walk in the woods.🍄📷

A note to my students 📚🤖🌱⛺️🏛️⚖️

Dear Students,

This spring I have been thinking about how best to welcome you to my classrooms this fall. If you’ve just graduated from high school, you might not know what to expect at university. For what it’s worth, a lot has been changing for us faculty too, so I’m not entirely sure what to expect either.

Certainly some things will be the same.

In my classes, we will be reading some texts that I consider great, like Plato, Aristotle, Augustine, Avicenna, Confucius. We will read them together, asking together what they say, what they mean, and what they mean for us today.

We will also spend time outdoors, reading the land around us. We will look closely at our campus and at our city and its environment. Students before you have shaped our campus by building gardens, an apiary, a stone classroom, and more. We will see those places and consider what might be done next. We’ll look at where the water in our city comes from, and where it goes, and who is affected by it as it flows. Lately I’ve been working with some non-profits and with the city government to try to make our city healthier for everyone. I’ll tell you about what we have done and I’ll invite you to join in this. I know all of this will be new to most of you, so don’t feel like you’ve got to make big contributions or changes. I’m just inviting you to notice it, and to consider how the gifts and talents and interests you bring to campus might add to what has already been done. We receive the world like a garden that others have made; now it is ours to tend that garden, to amend the soil, to grow good things.

To do that means we will also have to ask questions like “what things are good to grow?” And that will require us to ask what we mean by “good.” Yes, I’m a philosophy professor as well as a gardener and ecologist, so I often ask questions that seem easy to answer at first, until we look closely at them and discover how much we have taken for granted.

You’ve already got a sense of what’s good, by the way. You’ve inherited some of it from your family’s traditions, from your city and state and nation. Some of it you’ve cultivated by trying new things and discovering what works and what doesn’t work. You’ve probably got a sense of fairness, of beauty, of justice, of truth, etc. Let’s plan do what we can to refine and strengthen that sense for the long run of life ahead, and for building things worth inheriting. Let’s plan to become good ancestors together.

Together we will likely face some things that we don’t know how to tackle. You grew up with some powerful technology. Let’s plan to talk about how to use that technology well, and how to use it in a way that makes us better neighbors. How can we use technology in ways that makes us more virtuous, better at fostering goodness, fairness, beauty, justice, truth, etc. Feel free to reach out this summer, or to drop by my office this fall, if you’d like to know more about any of this. I work with IBM to help develop tech competitions, and I work with a local river conservation organization and our local zoo and aquarium to care for wildlife and to teach others to care as well.

You might also want to consider traveling with me. This fall I plan to camp for a night in the Badlands National Park to watch meteor showers and to listen to coyotes sing. Next spring I’ll be bringing students to study in Greece over spring break. Let me know if you’re interested in joining me.

I don’t know all that the fall will bring us. There are people who think that the best preparation for a class is in writing lesson plans and a syllabus and making online content. All of that has its place, and it has been part of what I’ve been doing this past year, anticipating your arrival this fall. But I’ve also been spending time in quiet contemplation; I’ve been traveling to a lot of interesting places and taking new classes so I can continue to be a student and not just a lecturer; I’ve been praying for you, because I am never confident that I know what’s best for you but I am wildly hopeful that you have immense potential within you and I am eager to help you grow and similarly eager not to impede that growth.

As you prepare for the fall, I hope you will take time to do some of these things as well. Consider what you value most, and try to write it down. What do you hope the story of your life will be someday? How do you want to grow? How do you hope you will be a blessing to others? How do you hope people will be remembered by future generations?

This fall, we will read some of those great texts together, and I look forward to reading with you the words of others who were once students like you, and who asked questions like these, hoping to become good neighbors and good ancestors. They will be our teachers, and together, let’s be the best students we can.

I’m looking forward to meeting you, and to sharing these experiences together.

Wishing you a joyful, restful summer,

Dave

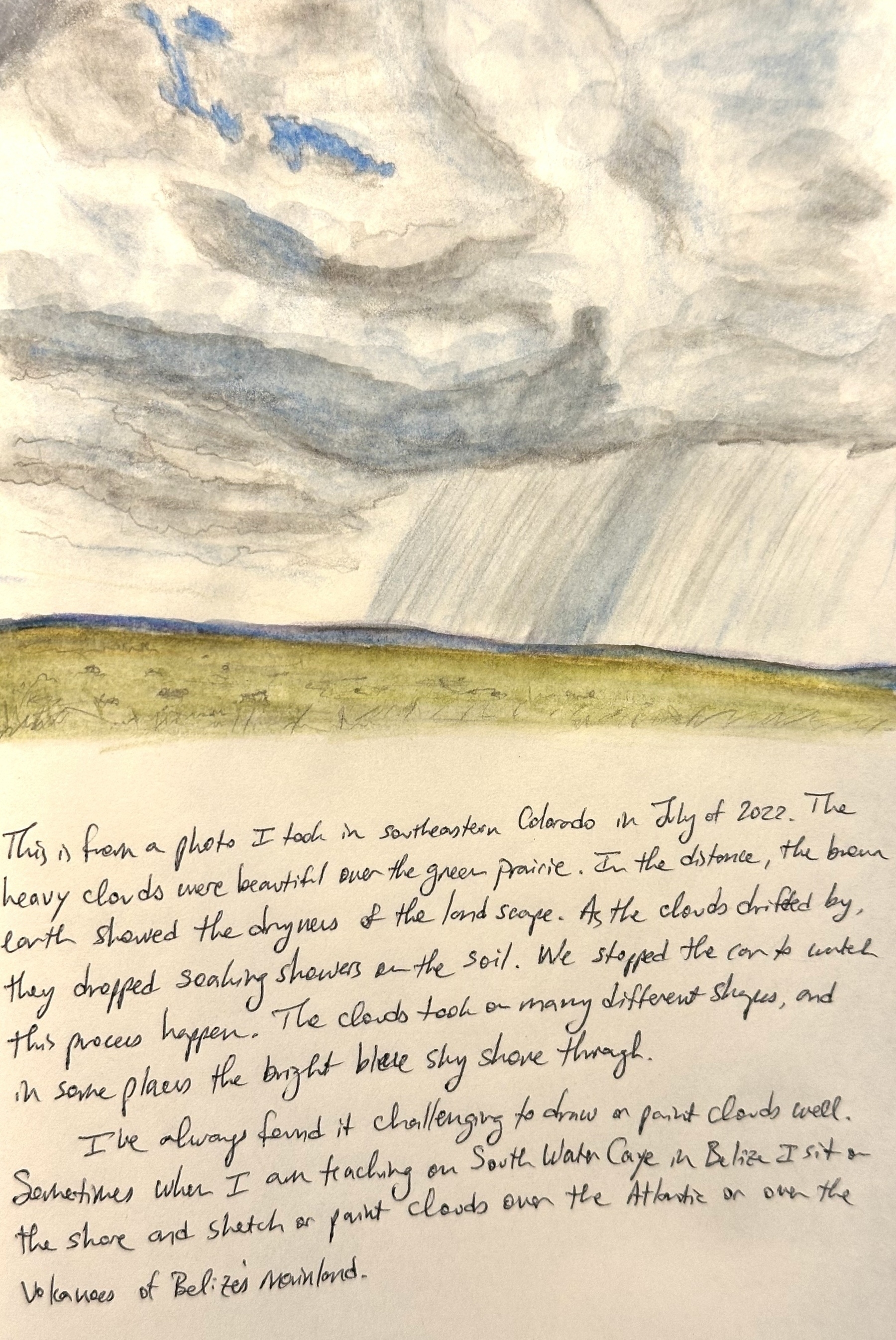

Rain for Claire 📝🎨

Today’s entry in the book I’m writing for my infant granddaughter.

I want to share stories with my grandchildren, telling them what I see in the world, and telling them about their family. I’m making records, and bearing witness to their new lives—and to the lives that surround theirs.

Ladybug on cup plant 📷🐞🌱

Herons on the Big Sioux River this morning.

Strawberries and mice for Felix 🎨📝🍓🐁

Every few days, I make new entries in the books I am writing for my grandchildren, both of them born in the last two months. They won’t remember much of this time, so I am doing some remembering for them. Here’s today’s entry for Felix. I hope he enjoys it someday. And I hope the mice in my garden are enjoying the strawberries this morning. I didn’t like the fact that they got the best strawberries first until I wrote about it and sketched this picture for Felix. The writing and the sketching made me glad as I imagined what the mice must feel when they adventure through the tall plants and find sweet, luscious strawberries as big as their heads!

Stairs

“As you sow, so shall you reap.”

It is easy to imagine what we want to reap, and to assume that what we are sowing will lead to that harvest.

It is harder to examine our gardening practices, to take a close look at our seeds, to tend our fields over a long time.

It is harder still to be honest when we see that our garden is not producing what we hoped, and even more challenging when what it is producing is toxic.

But what a delight when we find something good growing there, and we can harvest seeds and share them, and teach others to grow good things, too.

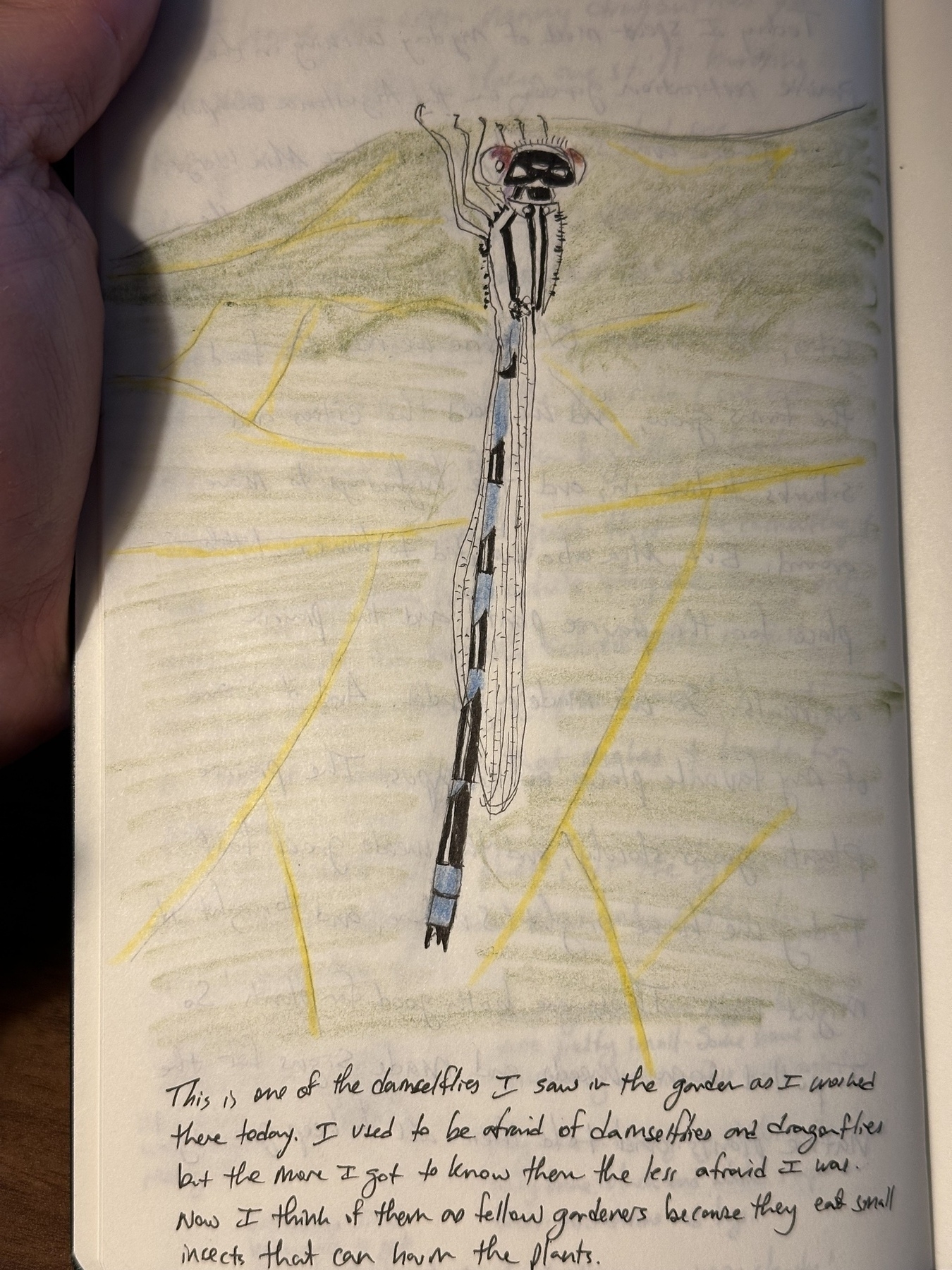

Letters to my Grandchildren

Every few days I add to the journals I am keeping for my newborn grandchildren. My two oldest kids became parents a few weeks apart, and I’ve been writing journals for the grandkids, to let them know what I am seeing in these first days of their lives. No strict agenda other than to offer them glimpses into their own development and things happening in the family. I hope they’ll appreciate them someday. I also try to include sketches. Today I wrote to my grandson about my work in the prairie restoration garden on campus, and included a sketch of a damselfly I saw.

Mother wood duck and some of her ducklings in the campus pond.

POV: you’re a bee small enough to get lost inside a dandelion.

Hylaeus bees (I think this is one of them, but I’m not 100% sure) are amazing.

Here it is, perched on a single petal of a dandelion.

Word on the street.

(Technically, words on the footbridge over Beaver Creek near Brandon, South Dakota.)

What has it got in its pocketses?

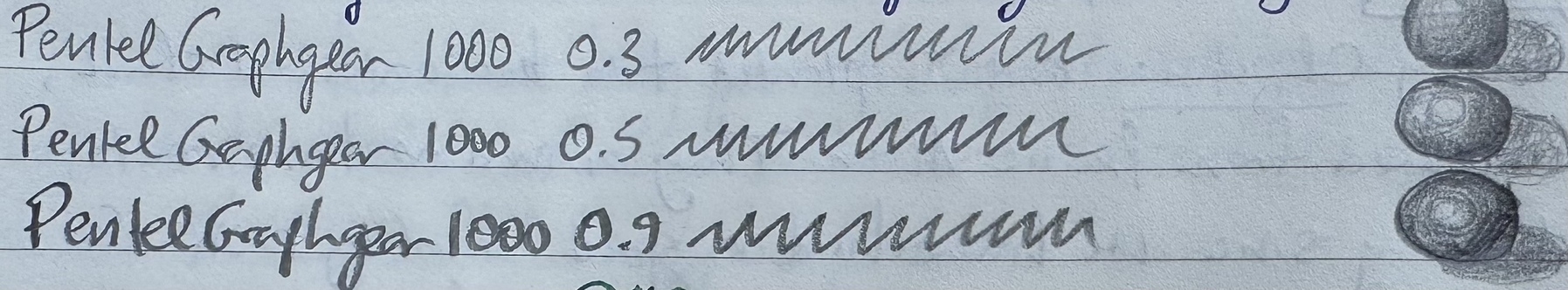

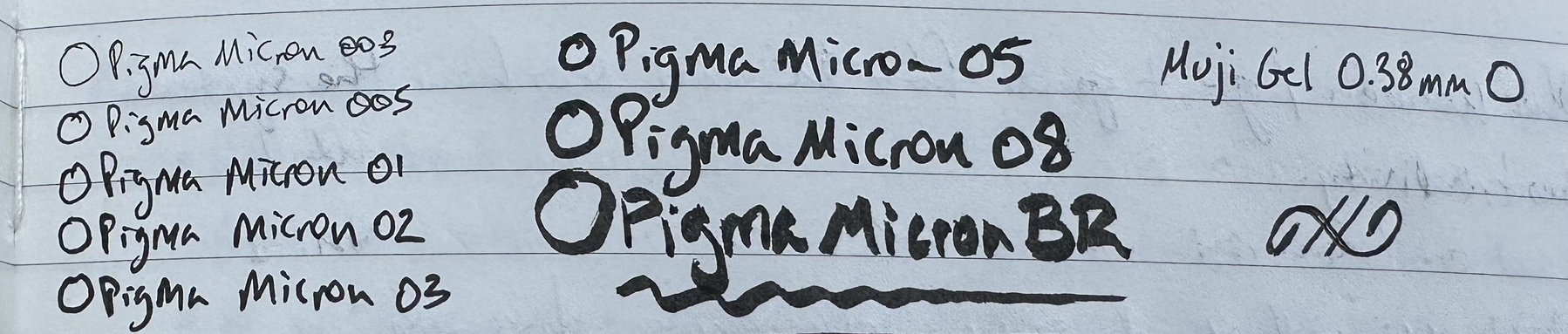

Some of my sketching EDC, in two photos.

The bigger your org, the greater the chance that there’s someone in your org who keeps things working well behind the scenes.

Find out who that person is and quietly figure out how to give them what they need to do their job well.

One of the few newsletters I read every week comes from this guy, @jthingelstad www.thingelstad.com/2025/05/1…

Graduation today. I’m gonna miss a lot of these kids.

Postscript to my previous post:

“Have you pen and ink, Master Doctor?” “A scholar is never without them, your Majesty,” answered Doctor Cornelius. – C.S. Lewis, Prince Caspian, ch. 13

Blue Books, Journals, and Letters to the Future

For many years, two of my favorite teaching tools have been oral exams and handwritten journals. When my bookstore stopped selling blue books years ago (back when we had a bookstore) for a little while I bought them from other sources. One big challenge: students often don’t carry writing instruments. Another: most of us have poor handwriting.

Oral exams are time-consuming, but when students take them seriously they turn the exam into something like a private class, and the aim becomes more and deeper learning.

Journals can be a hard sell, because the practice of journaling is so unfamiliar for most of my digital-native students. So I show them examples of journals from history. Pausanias. Henry David Thoreau. My mother’s journal from her trip to Europe after she graduated from college. (Mom died 14 years ago; I still have that journal.)

It’s not easy, but I teach students how to use journals as a practice of being present without distraction. And I ask them to think of a journal as an epistolary practice, writing to their future selves and to others whom they might someday know and love, like their great-grandchildren. (I have letters my grandfather wrote to his mother while he was fighting in the Pacific in WWII. What treasures!)

My sabbatical is coming to a close, and soon I’ll be back in the classroom. I’ve got some work to do to prepare for the fall classes. My students will be even more digitally-oriented than previous generations, and much of higher ed, including my university, continues to adopt digital “solutions” to education in the form of course management software, digital evaluations throughout the semester, quantified assessment of courses. All of those digital artifacts are ephemeral collections of binaries that will likely be forgotten.

Most likely I won’t be offering any blue book exams, but I hope to provide my students with opportunities to be present and still, to converse with those who have written letters from long ago, and to write their own letters to the future in a material, tangible form.

As I type this, I know this reflection is itself one of those bits of digitalia that will also likely vanish. Such writing can be worthwhile, but I don’t want them to completely replace the incarnate and haptic practice of holding a pen, of feeling the nib run across the fibers of paper, of stopping to think bodily about what to write next.

And as I write this I have before me a handwritten note from a student who will graduate today. She wrote to thank me for a course I taught in backcountry Alaska, where the only assignment was a handwritten journal.

She wrote, “I hope that we someday have an Alaskan reunion trip because that may have been the most transformative experience while at Augie!”

Well, I can think of a few things that she experienced while here that were likely much greater, but I am grateful for her handwritten words nonetheless.

And I hope that in the coming semester, my students will also write things that they will look back on with gratitude for the experience.