One Word

One Word

One word to the finches

Who perch on my towering sunflowers,

Who fling golden petals,

Who drop a thousand husks

On the garden below.

Who dive at my coneflowers, talons out

And then peck and pull and shred

Those spiny, spiraled heads.

It is September now, but I know

That you and others of your kind

Will be back again, and again

Perching in the branches

All fall, and all winter too.

And you will continue to feast

On the dry seeds that remain.

What was a colorful garden is becoming

Your harvest meal, your stores for winter,

And you don't care how much I worked

To make this garden grow.

The earth I turned, the soil I amended,

The compost churned, the toil.

The seeds I raised inside while you sat

On brown stems, looking in my windows.

The seedlings planted, and watered,

And watched until they grew.

I have just one word for you:

Welcome.

When you leave today I'll gather

A few of those seeds myself

And I'll set them aside to dry

So that next spring you, and I

Can begin to grow again.

—-

David L. O'Hara

19 September 2020

John T. Meyer Interviews Me On His Leadmore Podcast

John T. Meyer, CEO of Lemonly, is one of the best interviewers I've known. In his Leadmore podcast he has interviewed immigration lawyer Taneeza Islam, Governor Dennis Daugaard, Augustana University President Stephanie Herseth Sandlin, Vaney Hariri, epidemiologist Dr. Lon Kightlinger, and a number of other leaders.

I'm delighted to have joined him in this conversation about teaching as a kind of leadership; ancestral languages; and the value of learning what some might call "unnecessary" knowledge like the liberal arts.

You can find it wherever you get podcasts. You can also find it as a video here.

Environmental Studies At Augustana - My recent interview with Lori Walsh on SD Public Radio

| |

| The Augustana Outdoor Classroom, designed by an Environmental Philosophy class. |

Aldo Leopold wrote that "there are two spiritual dangers in not owning a farm." Those dangers both add up to this: losing touch with the land and so with the very things that sustain our lives.

You can hear the full interview here.

|

| Strawberries in spring bloom. Do you know where your food comes from? |

My thanks to Lori Walsh for being such a patient and thoughtful interviewer. In the past I've been interviewed while sitting with her in her studio. Phone interviews are new for me, and there's a little lag that has me talking over her unintentionally at the end. She rolls with it, unflappable and brilliant as always.

Philosophy of Liturgy, and Climate Grief

I admire Greta Thunberg for her passion and commitment. I similarly admire a number of my students for their constant concern for the environment. This world we share, “this fragile earth, our island home,” as the BCP calls it, should not be mistreated.

And it is being mistreated, by all of us.

The more you know about that, the more you feel as Greta seems to feel, and as Aldo Leopold felt, like someone who “lives alone in a world full of wounds.” In his book, Round River, Leopold wrote that

“One of the penalties of an ecological education is that one lives alone in a world of wounds. Much of the damage inflicted on land is quite invisible to laymen. An ecologist must either harden his shell and make believe that the consequences of science are none of his business, or he must be the doctor who sees the marks of death in a community that believes itself well and does not want to be told otherwise. The government tells us we need flood control and comes to straighten the creek in our pasture. The engineer on the job tells us the creek is now able to carry off more flood water, but in the process we lost our old willows where the cows switched flies in the noon shade, and where the owl hooted on a winter night. We lost the little marshy spot where our fringed gentians bloomed. Some engineers are beginning to have a feeling in their bones that the meanderings of a creek not only improve the landscape but are a necessary part of the hydrologic functioning. The ecologist sees clearly that for similar reasons we can get along with less channel improvement on Round River.” --Aldo Leopold, Round River, Oxford University Press, New York, 1993. p.165When we hear of a single wound, most of us offer to help mend the wound. Most of the people you meet are, after all, people of good will, people who love their friends and families and who want the best for their community.

When we start to hear of more wounds, we react differently, wondering what we can do to protect ourselves from being wounded.

And when we find that there are wounds everywhere, it’s overwhelming. Some people react by plunging into grief. Seeing that the world is in peril, they wonder why no one else sees the peril, or cares about it. The problem is immense, the resources to cope with the problem are few, and lamentation quickly becomes fragile despair.

Others enter a state of denial, or of resignation. That’s just how it is, they say. It’s the price we pay for progress, and we can’t go back. There is nothing we can do but move on and hope for better solutions in the future. Eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we might die.

Thing is, they’re both partly right.

The world is in peril. And the wounds are too many for any one of us to heal on our own today.

A liturgical calendar can help.

The Book of Ecclesiastes offers some helpful words: There is a time for everything under heaven. A time to heal, a time to rejoice, a time to mourn, a time to gather stones, and a time to cast stones away.

We need time dedicated to climate grief. This is like Lent, or Ramadan, or Yom Kippur, a time of fasting, of reflection on what we have done wrong, of repentance and turning away from our errors, of atonement. These are times for pausing to consider our lives and our connection with others. Lamentation of error is essential for learning to do better.

We also need time dedicated to hope. For every fast, there should be time for feasting. We need both the thin seedtime and the fat harvest. Just as we need to mourn our own ignorance and error, we need to celebrate the good things that are still worth seeking, striving for, and preserving.

Most people know the names of a few holidays. Few know the reasons for the holidays, or why they have lasted for so many centuries.

I’ll suggest that whatever tradition lies in your heritage or in the heritage of your community, take a little time to consider it. What rituals of fasting and feasting, of mourning and celebrating does it offer you? Religion is not without peril, of course, but it can also be a rich inheritance if you know what to do with it.

As you consider the liturgies you’ve inherited, remember that most ancient liturgical calendars follow the patterns of the heavens above. I don’t just mean that in some mystical sense (though there’s probably more there than we can easily grasp) but in the simplest sense: liturgical calendars follow days, weeks, months, and years.

It can be helpful to ask questions like these:

- How can I begin and end each day so that each day has a sense of being meaningful?

- How can we begin and end each week so that toil does not become the pattern of every waking moment?

- What are the times of year that give themselves to fasting and mourning, feasting and celebrating, so that we can meaningfully reflect together on the real wounds, and lament together over what we’ve done; and so that we can rejoice together convivially, eating, drinking, and being merry in the wounds that we have worked together to heal.

On Religion And Robots

Gracias, señora Orza

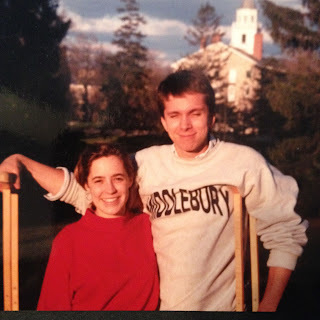

One day when I was in middle school in New York you said to me “You’re good at languages. You should go to Middlebury.” I hadn’t heard of it before, and I had been planning to attend the cheapest local college I could attend, to save my family the cost of college. Then you handed me a brochure from Middlebury, about their summer language programs. A year later, when I was leaving to work in Nepal for the summer, you gave me a blank journal as a parting gift, reminding me that writing matters.

I haven’t seen you since then, and I haven’t been able to track you down to thank you in person, so I’m firing this out into the internet to say thank you to you and to all the other teachers like you. Why? Because you changed my life.

Three years after I last saw you, I drove to Middlebury to check it out, and I fell in love with the place. I sat in on a Religion class (a subject I thought I wouldn't find interesting at all) and learned more about religion in that single hour than I thought possible.

So I applied, and I got in, with a scholarship. I guess they thought I should go there, too! Over the next four years that college made it possible for me to study in Spain; to learn to read and translate multiple forms of classical Greek; to be exposed to history as more than names and dates; to study physics, and math, philosophy, and even a little more religion.

Looking back on those years now, I see that my whole career has arisen out of classes I took there.

And best of all, I met this amazing woman! I think you’d like her. Like you, she’s smart and sweet. Like you, she encourages me to keep learning. And like you, she’s fluent in Spanish.

|

| We started dating in college, and we're still dating each other now, even though we're both married. I think you'd like her. |

Far more than the classes, she has changed my life. So often it's the people you meet--and not just the things you learn--that change you. I'm grateful to have met you both.

So thanks for being a Spanish teacher in a middle school in rural New York. Thanks for putting up with all of us kids in your classes, year after year. And thanks for taking my future seriously enough that you thought that my life, my travels, and my studies really mattered. You saw all that far more clearly than I did back then, but over the years I’ve come to see what you saw, and I’m forever grateful.

Your loving student,

Dave

On Paying Attention To Bear Poop - My recent TEDx talk in Fargo

The allegedly unnecessary things - like bear poop, and poetry - are often the things you most need to know.

I'm grateful to my friend Greg and his team for making this possible. I had no plans ever to do a TEDx talk until I met Greg through some mutual friends. We were having coffee here in Sioux Falls a few years ago, and I said something about the ecology of fish and forests. It must have resonated with Greg, because when I was done, he said "You should come to Fargo to give a TEDx talk!"

Some of the best things happen when you take time to have a cup of coffee or tea with friends, or when you meet new people, or when you find some bear scat on a trail by a river. Each of these things can be the prompting of a new thought, the spoor that shows you a new path.

Commerce, Environmental Attention, and the Liturgical Calendar

|

| Bighorn sheep in the Badlands National Park. The animals move together, responding to the land. |

By "liturgy" I mean the work we do together on a regular basis. The word "liturgy" comes from two Greek words that mean "the work of the people," and it usually refers to the rituals of worship in a religious congregation: it's the formula for when and how and where we stand, sit, kneel, pray, etc.

Most religions I can think of have liturgical calendars that describe the regular cycle of rituals in a year. If liturgy usually refers to what we do when we gather for a holiday or a day of worship, a liturgical calendar organizes the year so that we know when those days occur. It usually gives a sense of the flow of time, connecting days to one another with some purpose: liturgical calendars connect

- fasts with feasts,

- days of rest with days of labor,

- celebration with food,

- the progress of our days with the progress of the skies,

- remembrance with anticipation,

- rejoicing with mourning.

|

| Watching the seasons change: autumn leaves make imprints in the ice on my campus green. |

I used to think this was all silly, and a forced imposition on my freedom.

Lately I've been discovering that -- for me, at least -- the calendar's structure is a source of freedom from other calendars that don't help me to live well.

When I was younger I abandoned the liturgical calendar because I didn't want someone else telling me what days were holy. Why shouldn't they all be holy if I want them to be? And why should I fast just because someone else said we all should fast?

What I've come to see lately is that If we abandon the liturgical calendar with its times of feasting and fasting, the calendar doesn’t go away; it just becomes commercialized and turned into a calendar of constant consumption, constant labor. Feasting becomes purchasing; fasting becomes debt; and the two coincide with no time of rest between.

I experience the collapse of the calendar most where people like me have given it up and allowed others to co-opt it for commercial purposes. In simple terms, I experience it when I walk into a store in October and I hear Christmas music. All around me are ads telling me that my greatest obligation is to purchase things for Christmas, and to do so now.

This makes me want to shout: please spare me the Christmasy jingles, most of which drive me from your store. I like Christmas hymns, but the stress of being a cog in the machinery of holiday commerce has led me to appreciate the difference between Advent (a season of anticipation, of watching, and waiting) and Epiphany (a season of revealing, of celebration of birth, of discovery).

No one taught me this when I was young, but I've learned over the years that my tradition has different hymns for different times in the liturgical calendar. Now it feels odd to enter a pharmacy and to hear a hymn for the Nativity being played over the loudspeakers during Ordinary Time.

I used to think all that tradition to be nonsense. The older I get, the more I appreciate the thoughtful progress of a year, and the more I dislike the flattening of all days and all times into a yearlong, nonstop worship of commerce and toil.

We can't easily escape liturgical calendars, and I'm not sure we should. Even the birds of the air know when it is time to migrate, and they all have their liturgy of flight. The flowers know when to bloom, the salmon know when to spawn, the bears know when to look for the salmon. We humans used to know all these things, too.

Little by little we have lost connection to the liturgies that connect us to the land, the plants, the animals, the water, the wind, and the skies. When I ask my students what the phase of the moon is, it's rare that they know.

And I admit it is a wonderful thing not to need the moonlight. Running water, grocery stores, central heating, a solid roof, a functioning car, and many other modern conveniences are delightful. But they do come with costs; these good things are not free. They cost us money, which means we work more for them. And they have invisible costs, like the slow change of the quality of air in cities, the slow degradation of the planet's water, the slow loss of species around the world, the slow accumulation of things we throw away.

And then, when these slow processes pile up, we begin to notice them, and we begin to wonder: what have we done? We slowly gave up the liturgies of seedtime and harvest and replaced them with liturgical calendars in which all days are days of commerce and toil.

Which gives rise to new liturgies, urgent liturgies of anxiety. Look at what we have done, we say. With sackcloth and ashes we lament the fouling of our nest. As an environmental researcher, I see the fouling clearly and often, and I share that stress, that anxiety, that lamentation.

But if we replace the new liturgy of constant toil and waste with a newer one of constant lamentation over the toil and waste, we might wind up replacing one flattening of days with another.

|

| Seedtime leads to harvest, and then seedtime again, with times of rest in between. |

I don't know the solution, and I don't intend to argue for returning to some halcyon past. Nor do I plan to argue for the imposition of my chosen calendar on others. But I do intend to reexamine the calendar I inherited, to dust it off and see what I missed when I put it aside. Sometimes old ideas are still good ones; some old seeds can still bear new fruit.

For now, what I propose is to mourn in some seasons, but also to rejoice in others. If there is mourning to do, it is also the case that there is still life to preserve. Each of these things--mourning and preserving, looking back at what is lost and looking ahead to what might flourish--calls for its own day. And each day calls for a calendar that can connect it to the other days in a way that keeps each day from dissolving into atomic time. Each day has some part of the whole of life. That part is worth seeing in its own day.

On Living Imitably

Yesterday, knowing that I'd have this conversation today, I was in a reflective mood, perhaps more than usual. I was paying more attention to my daily life, I think. In the morning I taught a class on medieval philosophy. I spent some time moving stones in a garden on campus, part of a long-term project of making a meditative space for my community. I went to chapel. I met with a prospective student and her mother. Of course, I answered a lot of emails.

But one of the biggest things I did yesterday was I sat in my office with students and made them tea. And we talked about their studies and their lives.

|

| Mugs in my office, waiting to be filled. |

Tea is so simple: dead leaves and hot water. But the right mixture of leaves and water--and the right company--bring warmth to the hands and to the body; they deliver flavor and scent to the mouth and nose; they satisfy the gut in a remarkable way; they give a little stimulation of caffeine.

Perhaps most importantly, the tea, taken with another person, creates a moment. The moment lasts as long as the tea lasts, and then it moves on.

In those moments yesterday I talked with more students than I can quickly recount. (I have a lot of dirty mugs to wash when I get to the office today!) What they all wanted to talk about: how to live well.

One wanted to talk about her spiritual journey and her education, and how they meet and complement one another. Actually, quite a few wanted to talk about that.

Several wanted to talk about how to change the entire world, and to make it better for those who follow. That is, they had ideas about living sustainably, ideas that might be worth imitating, ideas that could grow and scale up.

There are times when I wish I had less paperwork to do, fewer reports to write, fewer exams to grade. (I'm falling behind in all of that, I admit.) And there are times when I wish I could seize the academy and just change it dramatically, because change in the academic world happens at a glacial pace. (And these days, the pace of glaciers is not hope-giving.) And of course there are times when I wish I had more money to give away, and that somehow the money I was paid corresponded to the amount of work I do. (Don't we all?) (Note to students: a Ph.D. in the Humanities is not a get-rich-quick scheme. FYI.)

Every year I think about leaving academics and starting up a business. When I am working for myself (yes, I've done so a number of times) I am also pretty happy. I like working with my hands, moving stones, writing books, guiding others through wild places. I like finding value where others don't see it, and then sharing that value broadly.

Today is not the day I will leave the academy, I think. Those conversations yesterday left me with the sense that while I could make a lot more money elsewhere, I am happy with the fact that I am making a difference right where I am. Maybe today's conversation will change that. In fact, I hope it will change me, at least a little. Good conversations should do that, just as pausing to look at the compass should change or at least verify the direction we are taking. After all, as I remind myself often: students are watching my trail, and some are following along behind me. The decisions I make matter for more than just my own life.

I hope today gives you a moment to pause, perhaps with a friend and a mug of something that warms you both, and with a compass that will help you to determine whether the path you are taking is worth continuing on, and imitating.

Perennial Thinking in Education, Ag, and Culture - Lori Walsh interviews Bill Vitek and me on SDPB

One of the persistent themes of his work is the connection between culture and agriculture: the two shape one another.

|

| A bit of prairie, with perennial grasses. |

Another theme that is related to the first: we all eat, and we all think, and eating and thinking indluence one another.

A third theme: we tend to focus our thinking on the annual or the short-term, neglecting the perennial and long-term. having spent a few days with Bill, I'm now reflecting on what I find one of the most provocative parts of his work: what would it mean to shift from thinking of education as an annual crop to thinking of it as a perennial? Currently we begin planting at the beginning of the season, and we expect to harvest grades and graduates at the end of the term.

What if we thought of education in the way we think about caring for perennials? What if we considered school to be more like the planting of trees than like the planting of corn? Or what if we figured out a way (as they are doing at the Land Institute, where Bill is a collaborator with Wes Jackson - here's a link to one of their co-edited books) to give our annual crops perennial roots?

|

| A view of the Augustana University campus, with historic buildings. |

I have a lot of work and thinking and cultivating ahead of me, so I won't answer those questions here. If you have taken my classes, you already know how I have been working on this over the years (think of how I speak about grades and exams in my classes, for instance). And if you've read my books (like my book on C.S. Lewis' environmental thought, or my book on brook trout as indicators of both natural ecology and cultural ecology), you know I'm working on these ideas, and they will require long cultivation. I'm okay with that.

For now, feel free to listen to Bill and me as we are interviewed by Lori Walsh on South Dakota Public Radio.

Could a Robot Have a Mystical Experience?

This is something I've been contemplating for a while, for a variety of reasons. It's not that I think that robots are about to have organic religion (that's not for me to say) but increasingly we are delegating small decisions to machines. We should prepare ourselves for times when machines will claim the right to make big decisions. The machines might be making such claims because they are self-conscious, but they might much more easily make such claims because it's easier to sell us products or political views when they come with the stamp of the divine.

It's worth linking back here to a previous post, if only to point out how helpful Evan Selinger, Irina Raicu, and Patrick Lin have been as I think about this. None of them should be blamed for my oddities or errors, but all have helped me to think more clearly.

Ants and Grasshoppers, Wasps and Cicadas

The Ant and the Grasshopper (or Cicada)

We’ve been thinking about cicadas for a long time. In his well-known fable, Aesop compares cicadas to those industrious hymenopterans, the hardworking ants. (Ants, bees, and wasps are all hymenopterans. Sometimes Aesop’s word “cicada” is translated as “grasshopper.”) Bernard Suits' book The Grasshopper reminds us of the timelessness of that comparison, and asks us to consider the place of play in a well-lived life. (Incidentally, there's a playful restaurant in Athens' Syntagma neighborhood called Tzitzigas kai Mermigas.)

Students of ancient Greek Philosophy will remember the cicadas in Plato’s Phaedrus. That text offers us a rare glimpse of Socrates outside the city walls. Cicadas hum loudly overhead when Socrates ironically declares that he is still trying to examine himself, and so he has no time for the cicadas’ sweet song. A little later on, Socrates (again, ironically) returns to the cicadas and suggests that their song is a distraction for those who would examine their lives in conversation with other people. (Aesop: Perry 373; Plato, 230b, 259a)

It’s no surprise to me that cicadas figure in these and other classic texts from around the world. Cicadas are both beautiful and mysterious to the young naturalist. Cicadas spend most of their lives underground. Late in life, they emerge and shed their exoskeleton. Their adult lives will be short, but full of singing, flying, and mating. Not a bad way to go, I think.

Cicadas can also be pests. Their noise can suck the calm out of a summer evening, and these subterranean tree parasites also suck the life out of trees.

The Myth of the Wasps

But it’s not the cicadas that interest me this year. Instead, I’m looking at the hymenopterans. Around this time of year another species emerges with the cicadas: cicada killer wasps (sphecius speciosus).

These two species have a lot in common. Like the cicada, the cicada wasps live underground for most of their lives; they become winged adults around the same time; and they die after mating. The wasps emerge from their burrows with mating fervor and haste. They move fast, darting and banking suddenly. The males joust with one another, constantly changing direction and speed. These are some of the biggest wasps we have, thick as a pencil and up to five centimeters long. They have huge eyes and long, black-and-yellow-striped bodies. They look dangerous.

They look dangerous, but they're not very dangerous to most of us.

Looks Can Deceive, For Good Reason

Contrary to their appearance, they don’t pose much threat to humans. My instinct on seeing huge, fast wasps is to run, or to swat them away. Evolutionarily, this is probably a good instinct. We fear creatures that look like they sting and bite because some of them can hurt us.

When I was a child, that fight-or-flight instinct was strong. Growing up in the Catskill Mountains, I learned to avoid snakes, spiders, and wasp nests, and to be on the lookout for larger predators like bears. One day when I was playing at the wooded edge of our lawn, Dad ran outside to tell my brother and me that one of the neighbors had just seen a bobcat nearby. We were small, and folks were worried. Would a bobcat attack a child? We all eyed the woods warily, and for weeks afterwards we distrusted the forest.

Fighting for Food Is Expensive

In my two decades of teaching environmental studies, I’ve come to realize that most of the creatures I encounter in the wild don’t want to tangle with humans. The wasps are interested in other wasps, and in cicadas. Like my father that day in the Catskills, the wasps are looking out for their families, and in doing so, they’re incidentally tending a garden from which other creatures benefit. As the name suggests, cicada killer wasps hunt cicadas to feed their offspring. By limiting the population of the cicadas, the wasps help the trees, which helps everything that depends on the trees, even the cicadas that survive and mate. Female cicada killer wasps paralyze cicadas with their stinger. Then they drag the cicadas into their burrows. The wasps lay male eggs on single cicadas, and female eggs on multiple cicadas. (The females grow bigger and need more food, so a female egg gets a bigger larder.)

A female cicada killer wasp won’t sting you unless you force her to. Grab her hard and she will fight back. Leave her alone, and she will leave you alone as well. Likewise, the stingless males might seem threatening, but they’re just looking for love, sometimes in the wrong places. The reason why they are flying so fast? They’re competing for mates, and they’re looking for a female who is ready to breed. All of those adults flying around right now will be dead in a few weeks; they’ve got work to do, and little time to do it. All of their children will be born in solitary burrows, lonely orphans. Their parents are doing what they can right now to make sure that those orphans survive. And so the cycle repeats itself.

Why does any of this matter?

First, I’m telling you a little about my work as an environmental philosopher. I don’t just study animal ethics and ocean policy. Much of my time is spent trying to observe the world around me. Like Thoreau and Aristotle before me I want to learn what I can about the lives I share this place with. Some of my research is done in journals and books, but a lot of it is done outdoors. I study salmon in the Arctic, I take my students diving on reefs and trekking through forests, and we spend time just watching the wasps and cicadas here on the prairie.

Second, I want to affirm that your fears of wasps and bees and snakes are natural and even reasonable. That instinct has helped our species survive and to care for our families, just like the instincts of the cicada killer wasps help them. There’s no shame in that.

Which brings me to my third point: the fears may be natural, but firsthand experience and liberal education can go a long way towards moderating those fears. The fears are limbic, buried deep in our genes and brains. But that should not satisfy us; we should take Socrates’ famous words about the examined life to heart, and examine the fears that constrain our decisions.

It’s reasonable to fear wasps in general, but the more you learn about wasps and bees, the more you’ll see that most of them want nothing to do with us. Think about it: we can kill them with a swat. We are giants in comparison to the biggest wasp in the world. For some hymenoptera, stinging us is expensive. Some bees die when their stinger is torn from their body. When wasps sting, they draw on their limited supply of potent toxins. Something similar is true of venomous snakes: it’s metabolically expensive for them to produce venom, and it’s extremely risky for them to attack something as large as an adult human. Most of them, given the choice, will avoid us. I see this in my fieldwork in the far north and the far south, too: many large carnivores like jaguars and brown bears would rather avoid me if they can. Animals, like humans, don’t want to spend more for a meal than necessary.

(Of course, scarcity of food can justify greater expenditure of energy to make sure you have a meal. This is why, as the arctic is losing its ice, polar bears are walking farther and farther in search of food. This year several polar bears have been found an extraordinary distance from the ocean. Hunger can make migrants of us all.)

This brings me to my last point: I’m not just writing about bees and bears, after all, but also about politics. The cicada killer wasps are a living parable, a fable with a moral. You and I have some prudent fears that are built into us.

It makes sense, on an evolutionary scale, to be fearful rather than trusting, and to avoid the unfamiliar. It makes sense to be wary of immigrants whose language, clothing, diet, cultural practices, and aromas differ from those of our friends and family. Likewise, it makes sense to be standoffish when you have had a bad experience with someone who does not walk, talk, or look like the group you most associate with.

Making fresh decisions costs us calories in mental effort, so we save our energy by limiting our social sphere. The echo chamber is comfortable because it’s an easy lift. Anyone who requires you to learn new vocabulary or new ways of thinking about love, family, politics, money, faith, recreation, food, or the other things that make up our lives is someone who costs us the energy we consume in making new decisions.

It’s tempting to look to simple technology to make our lives easier. It would be much easier to build higher walls, spray stronger toxins, create more information filters to choose our reading for us, and never to learn the names of those affected, as though we didn’t share an ecosystem.

As though we were not quite similar to one another. As though we did not all love our families. As though only some of us understood the value of hard work. As though we did not depend on one another. Kill the ones we have called the killers and be done with them.

But if we do so, we remove them from the system we share, and we leave a gap. Without the wasps, the cicadas lose a species that serves their species. If the cicadas multiply, the trees will pay the price. If we kill the wasps, we pass the buck along to the trees, and to everything that depends on them, including ourselves.

The Fable of the Bees, and the Examined Life

In Bernard de Mandeville’s Fable of the Bees, he makes the claim that we are all driven by innate mechanisms and drives. Evolutionary theory backs that up, to some degree, but we’re not just machines.

We’ve got the capacity to examine ourselves, and to learn, and to make some changes. We might all be born with a fear of snakes, spiders, and wasps, but if we take the time to learn about them, and to learn about what drives them, we might find that we fear them less and welcome them more readily.

Could the same be true of our fellow humans who differ from us? For me, at least, this has been one of the best lessons of being an environmental philosopher.

Fellow Gardeners

Recently I was working in my garden here in South Dakota. Two male cicada killer wasps were feeding on the tiny blossoms that are just opening up on my mint plants. One of them, perhaps startled by my arrival in the garden, flew up into the air and bumped into me, then righted himself and flew off. The other sipped nectar and continued to hop around the garden. A moment later, the first one returned. He got over his fear and went back to eating. As they ate, they helped to pollinate the flowers, as so many bees and wasps do. My garden will bloom again next year in part because these “killers” helped me with my gardening.

I’ve also gotten over my fear, although it took me a lot longer than it took that male wasp. Little by little, as I’ve paid attention to the small creatures around me and tried to learn their names, I’ve come to welcome them as neighbors. I’m trying to learn their language, and to appreciate their culture. I’m glad to share the garden with them.

Books Worth Reading

This post will be a little different. At the end I’ll share some new books I’ve been reading recently, but I’m going to start with some older books.

Three Older Books

China in Ten Words (Yu Hua, 2012; Allan H. Barr, translator) This is not very old, but it gives a history of some of the ideas that shape modern China. Each chapter considers one word and the way it exemplifies or illustrates something important about Chinese culture, especially since the cultural revolution. This has helped me to understand my Chinese students better, and it gives me more insight into Chinese politics, international policy, and economics. Yu Hua is a novelist, and his stories make for smooth, inviting reading. This spring I was teaching a class with students from ten different countries. At one point, one of my students from another country asked me why American schools are so concerned with plagiarism. Most of the other international students nodded in agreement. It was a helpful reminder that our American notions of intellectual property and academic integrity are tied to our idea that we are first and foremost individual agents, and it is individuals who bear responsibility for their actions and who gain the rewards for their achievements. Whether that’s true or not is debatable, but we don’t seem to have escaped from the Cartesian notion of the radical individual, the Protestant pietism that emphasizes the fall and redemption of the individual soul, or the Jeffersonian idea that rights and happiness are expressed in the individual. Over the last fifty years, China has shifted in that direction, to be sure, but China is still deeply in touch with both its Confucian sense of community and the aftereffects of its century of revolutions.

Out of the Silent Planet (C.S. Lewis, 1938) This is Lewis’ sci-fi novel about Mars. But of course no novel is ever about Mars; mostly, novels about Mars are about this planet and its inhabitants. Along with Lewis’ essay “Religion and Rocketry” (originally published as “Will We Lose God In Outer Space?”) this novel is important because it is a subtle invitation to examination of why we want to go to Mars in the first place. For me, it is one of the most important works of the ethics of space exploration, for a number of reasons. If you want all my reasons, feel free to buy my book on C.S. Lewis. Here’s one reason: most alien-encounter stories we write begin with the assumption that the aliens are the bad guys. Lewis wants us to consider that if we find our planet has gotten too uncomfortable for us, maybe we’re not the protagonists of this story.

The Way We Live Now (Anthony Trollope, 1875) This is about the 2016 election in the U.S. — but it was written in the middle of the 19th century in the U.K. I read this back in the summer of 2016, and I thought, “Oh, D.T. is going to win the election.” I won’t say it’s prescient, because it’s not explicitly about any future event, but Trollope does a good job of showing us what motivates us, how shallow those motives can be, what we will sacrifice to achieve them, and other perils of modern political life.

I’ll end this section with three unrelated books that nevertheless seem related to me: Charles Dickens’s Bleak House; Herman Melville’s Bartleby the Scrivener; and William Faulkner’s Go Down, Moses. Two things tie these books together for me: all were recommended by friends, and all have something to do with chancery courts. I have liked Melville for a long time, and I rarely regard time spent in his prose as time wasted. Dickens and Faulkner I like far less. I read Dickens as a portrait of his time, and time in his pages is like cultural archaeology. But it’s also like listening to someone make a short story into a long one while you’re trying to get to your next appointment. Faulkner is not at all like Dickens in that regard. He condenses his ideas so much that everything needs to be unpacked. Reading Faulkner quickly is unsatisfying; reading Faulkner slowly is tiring. For different reasons, Faulkner and Dickens are both tedious reads for me. Both of them make me lose the plot, one because he’s too fast, the other because he’s too slow. But in neither case is this a flaw in the author; I’m just highlighting a difference between the way they think and the way I think. Good friends recommended them, and that matters: reading what others care about can be a work of love and of fostering mutual understanding.

Should We Still Be Reading Books?

I read a lot of books each year. Usually when I tell people how many books I read, I am met with wide-eyed disbelief, so I won’t bother to tell you how many I read in a year. Instead, I will invite you to consider the importance of books. Recently I asked a group of graduate students about their reading habits. Some said they read about a dozen books a year in addition to required reading for their classes. I thought that was pretty good, considering how busy they are. But a few told me they get all their information online, mostly in condensed form through synopses and through Twitter. I don’t disparage the value of reading quickly and of foraging in the rich banquet hall of small parcels of always-ready information that our new technologies afford us. We live in rich times, indeed. I only hope that those graduate students will supplement their diet of fast reading with some slow reading and even with some fasting for contemplation and digestion.

There are some problems with books, to be sure. For one thing, they take a long time to read, and some of that reading (as with Dickens) can be slow going. For another: they take a long time to write. A third thing: the barriers to publication mean it’s easier to find books by people with connections to publishers than books by rural writers, non-English writers, etc.

But books are durable. I started writing this blog post on my tablet, and then the battery died. That never happens with books. Books are resilient, or super-resilient. Consider the way John Steinbeck’s The Moon Is Down spread across Europe during the Second World War. We think social media are fast today, but Steinbeck’s propaganda novel spread rapidly because each time someone read it they made the decision whether to copy it, and many people copied and translated it. Decisions like that are much costlier than retweeting something you glanced at, and so they carry much more weight and value. And once a book like that is copied, it’s very hard to delete it. How many books have been written about both the danger books pose to people clinging to power? And then there’s that old question about which books you’d bring to a desert island; how many of you would choose to bring a laptop or a tablet? The salt air and heat would kill it quickly even if you had solar panels to recharge it. Books are hard to beat.

|

| Some of my recent reads. |

A Few Recent and Current Reads

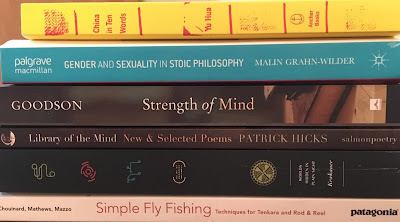

I’ll wrap up with a few recent reads, all of which I recommend, and all of which I’ll post here with minimal commentary:

Edward F. Mooney, Excursions with Thoreau: Philosophy, Poetry, Religion. (2015) Someday I would like to write like Ed Mooney. His book on Henry Bugbee was a confirmation that it’s acceptable to write academic philosophy in a way that is both clear and readable. (James Hatley did this for me in some of his articles, too. I’m grateful to both of them for that.) Now I’m very much looking forward to Mooney’s next book, Living Philosophy in Kierkegaard, Melville, and Others: Intersections of Literature, Philosophy, and Religion.

Patrick Hicks, Library of the Mind: New & Selected Poems. If you’re not reading poetry, what has gone wrong with your life? Never mind, don’t try to answer that. Instead, just read good poetry. Here’s an excellent place to start. Each page makes me slow down and collect myself again.

Malin Grahn-Wilder, Gender and Sexuality in Stoic Philosophy. I teach ancient and medieval philosophy, and I find books like this keep me sharp. The organization of the book is excellent, and so is the content. This is a nicely written history of ideas, and a useful resource for scholars.

Jacob Goodson, Strength of Mind: Courage, Hope, Freedom, Knowledge. I’ve known Jacob for a few years, and I like everything he writes. This is no exception. Jacob’s an excellent teacher with an encyclopedic mind. I have the good fortune of spending time with him in person each year, and those conversations become miniature seminars that leave me feeling refreshed and energized; he tills the soil of the mind. So you should buy this book and enjoy it. But I’m especially looking forward to his next collaboration with Brad Elliott Stone, Introducing Prophetic Pragmatism: A Dialogue on Hope, the Philosophy of Race, and the Spiritual Blues. That will be out later this year.

Evan Selinger and Brett Frischmann, Re-Engineering Humanity. This is one of a small number of books that I’ve gone back to multiple times. Selinger is worth following on Twitter for a daily dose of sharp observations on how we are letting technology race ahead of ethics. Once you’ve looked at what he posts there, you’ll find you’re either ready to check out of digital life altogether, or to go into the deep dive of this book so you can get a better handle on what to do next.

Yvon Chouinard, Craig Mathews, and Mauro Mazzo, Simple Fly Fishing: Techniques for Tenkara and Rod & Reel. Revised second edition, with paintings by James Prosek. Come for the zen-like techniques, stay for the beauty of each page, and take the time to read those small things like why Chouinard mapped several unmapped mountain routes, then burned the maps. “But standing around the campfire one day, we decided to burn our notes…There need to be a few places left on this crowded planet where ‘here be dragons’ still defines the unknown regions of maps. Then I went fishing.” If you follow me on social media, you know I write about trout and salmon. You might also know, if you pay close attention, that I love the places that the fish live, I love swimming with the fish, and I love the things and people they’re connected to. But the more I fish, the less I feel the need to fish, and the happier I am being near the fish. Tenkara rods are a very old way of being still with the fish.

David C. Krakauer, ed. Worlds Hidden In Plain Sight: The Evolving Idea of Complexity at the Santa Fe Institute 1984-2019. This is one I’m working through slowly, and I’m not reading it cover-to-cover. The organization of this book makes it one that invites a bit of flaneurism, reading deeply and thoughtfully, but in the manner of what Thoreau calls “sauntering”: not a linear, business-like drive to the finish line, but a walk without purpose other than to see what is there. This is one of the best kinds of learning. The book is, indirectly, about the importance of cross-disciplinary reading; the importance of philosophy of science for everything from understanding markets to climate change; and the helpful and constant reminder we don’t know enough about the things we quantify, even though we talk about the quantification with such authority. The book is priced at about ten bucks, but it's worth far more than that.

Is there something better than reading well-considered words? Perhaps, but all of these books have so far been well worth my while. I hope you have good books in your life as well.

My Interview With Lori Walsh on South Dakota Public Radio

On Telling Stories

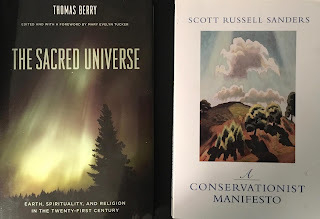

“Knowing on some intuitive level that we humans are guided by story, he ultimately called for the telling of the universe story. He felt that it was only in such a comprehensive scale that we could situate ourselves fully. His great desire was to see where we have come from and where we are going amid ecological destruction and social ferment. It was certainly an innovative idea, to announce the need for a new story that integrated the scientific understanding of evolution with its significance for humans. This is what he found so appealing in Teilhard’s seminal work."

-- Mary Evelyn Tucker, in her preface to Thomas Berry’s The Sacred Universe. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009) (emphasis is mine)

“I’m one who dwells outside the camp of literary theory—so far outside that I can’t pretend to know much of what goes on there. I know scarcely more about deconstruction or postmodernism, say, than bumblebees and hummingbirds know about engineering. I don’t mean to brag of my ignorance nor to apologize for it, but only to explain why I’m not equipped to engage in debates about literary theory. What I can do is express my own faith in storytelling as a way of seeking the truth. And I can say why I believe we’ll continue to live by stories—grand myths about the whole of things as well as humble tales about the commonplace—as long as we have breath.”

-- Scott Russell Sanders, A Conservationist Manifesto. (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2009) (emphasis is mine)

A few years ago my wife and I, along with another family at our university, established a scholarship for Native American and First Nations students who wish to study to become storytellers. (Feel free to add to it by giving here if you are so inclined.)

Some people have since asked us why we did not invest our money in something more practical like helping individual students get into business or medical school. After all, that's where the money is, and higher income can correspond to greater independence and greater influence.

We see their point, but we both have committed ourselves to what might be considered storytelling disciplines because we think that stories shape lives and communities. A free society depends on good investigative journalists, good attorneys, and good public schools. A thriving society depends as well on good art and literature. And while religion has its downsides, it also has very strong upsides, and communities draw great benefit from healthy faith communities that remind us of our values, that give us places to congregate, to engage in commentary and contemplation, to welcome new life, to sustain commitments, to help us to mourn.

We often talk about the importance of STEM disciplines and healthcare, but I think we would do well to pay a little more attention to the way that good storytelling shapes healthcare (and the way bad storytelling makes us doubt good health practices like vaccination, for instance.)

I am persuaded that stories shape communities. They take what we have received from the past and transform and transmit it. If I am right, then I am prudent to invest in good storytelling. In the case of Native American and First Nations communities, I know just enough to know that there's a lot I don't know. And I'd like to know more.

I've been working with Bio-Itzá, a small Maya Itzá environmental group in Guatemala for the last decade, and I am constantly learning from the stories of their few surviving elders who grew up hearing the Itzá language spoken. The preservation of those words and stories means not just the preservation of a few tall tales, but the preservation of everything that is encoded and deeply rooted in those stories. The stories are cultural and ecological palimpsests, and when the Itzá elders tell them, they are passing on far more than mere words.

So my wife and I are committed to helping others to tell their stories. Because "we are guided by story," and "storytelling [is] a way of seeking the truth," and "we'll continue to live by stories."

Reason For Hope

Apologetics and Postmodernism

When I first taught it, I made it a class about apologetics and postmodernism. By “apologetics” I mean the work of giving a reasoned account of one’s commitments; by “postmodernism,” I mean the suspicion that what look like reasoned accounts might have unexamined depths and layers to them. In the context of theism—and in particular Christian theism—apologetics has a long history that reaches back to the early years of Christianity. Saint Peter wrote in his longer letter that Christians should always be prepared to give a reasoned defense of the hope they bore within them. That phrase “reasoned defense” is a translation of the Greek word apologia, which can mean a legal defense, and from which we get our word “apologetics.”

When Saint Paul of Tarsus found himself in Athens, speaking to Stoic and Epicurean philosophers on the Areopagus, he tried to explain his beliefs not in the terms of his culture but in theirs. He doesn’t seem to have won many over to his views that day, but if nothing else was accomplished, at the end of the conversation it was clearer where Paul and the Greek philosophers were in agreement and where they disagreed. If immediate conversion was the aim of his speech, it wasn’t a great speech. But if he aimed to build a bridge of mutual understanding, I’d say he was pretty successful.

One of the keys to his success, I think, was familiarity with the culture around him. I’ve written about this elsewhere, so I won’t belabor it here, but I’ll just point out that Paul quoted two Greek philosophical poets, Epimenides and Aratos, and he did so in a culturally appropriate and significant place, since several centuries before Paul’s travels, Epimenides (who was from Crete) also traveled to Athens and also spoke on the Areopagus about the gods and salvation.

Understanding Atheism(s)

A few years after I started teaching that course, I shifted the course to take seriously the “New Atheists.” I figured that if my religious students graduated without hearing the strongest challenges to their faith, I, as a professor who teaches theology, was letting them down. I wanted them to know that soon they’d hear strong arguments against their religious heritage, beliefs, and practices, and that these arguments should be taken seriously. For my Christian students, I framed this as a way of living the commandment to love God with one’s mind.

Of course, only some of my students are religious, and some of the religious students aren’t Christians. (I’m at a Lutheran university in a small Midwestern city, so until recently most of them were at least culturally Christian; that’s changing quickly, though.) I wanted this to be a class that was helpful for everyone, so I started to turn this into a class about mutual understanding. I now teach my students how to distinguish between a dozen different kinds of (and reasons for) atheism, lest they make the mistake of oversimplifying the complexity of their neighbors and of themselves.

Understanding and Agapic Love

Arguments about religion can quickly become unkind. Many of us have been wounded in the name of religion, and those wounds heal slowly, if at all. How could we make this into a class that was—on its surface, and in its content—about theology and philosophy, while really making it about something like mutual care?

I just mentioned that great commandment: Love God with your heart, soul, mind, and strength, Jesus said, echoing Moses. Then he added a second commandment: love your neighbor as yourself. Everything else hangs on these two commandments, he said.

Explaining those two commandments would be almost as hard as trying to keep them, so I won’t try to do so here. I’ll just point out that it’s fascinating to command someone to love someone else; that the love that’s called for here is agapic love, i.e. the love that seeks the good and flourishing of the beloved; and that the commandments are so lacking in specificity as to call for both extensive commentary and continued practice. They’re vague commandments, which means they require us to work them out in community, over time. And in all likelihood we’ll never get them right. That may seem like a weakness, but it also strikes me as offering the freedom to try and to fail and to help one another to try again.

Anxiety, Ultimate Concerns, and Societal “Stress Fractures”

Which brings me to the most recent incarnation of my Theology and Philosophy in Dialogue class. Over the last few years it seems to me that my students have become more anxious about their economic futures, more stressed about exams and jobs, more focused on education and work as competition for rank. I could be wrong, but as the stress and anxiety have grown, it seems like my students are so busy jockeying for position that they have a hard time putting the cause of their stress into words. On top of all this, here in the United States, it feels like we’ve been using stronger words so that we can give voice to our anxiety more quickly. We aren’t broken, but we’ve got lots of hairline stress fractures that are too small to see. We aren’t bleeding, but we’ve got a constant dull ache.

In other words, it seems like we’re fearful without being able to identify the object of our fear, and that has us prepared to see enemies wherever we look. This does not make it easy to love our neighbors as ourselves (unless we also have that kind of distrust of ourselves, which is a real possibility, I suppose.) And at least in the way Paul Tillich described God: whatever we regard as our ultimate concern functions as our God. When economic anxiety, jostling for rank, or fear of losing one’s place in the future, (these are all ways of saying the same thing, I think) take on the role of “ultimate concern” in our lives, they become our gods.

The course I’m teaching this semester still has traces of every previous semester’s influences. We talk a little about apologetics, and that’s a helpful way of teaching students about logic, inference, probability, and certainty. (Ask some of them about “doxastic certainty” or my “haystack problem” and you’ll see what I mean.)

And we still talk about postmodernism, though as my career has shifted from the philosophy of religion to environmental philosophy, ethics, and policy, I’m inclined to follow Scott Russell Sanders’ view (see note, below) that if we spend too much time theorizing and not enough time caring for the world we share, incredulity towards metanarratives can quickly become a new metanarrative that we fail to examine sufficiently.

And we still talk about atheisms. This semester I have sketched a dozen forms of atheism once again, and we’re now working our way through them.

Friendship, and “Best Construction”

But the aim of the class, more than anything, is friendship.

I told all the students that this was the case on the first day of class.

And here, I think, is where Theology and Philosophy can have a really helpful dialogue in our time. I teach at a Lutheran university, so it’s fitting to invoke Luther. In his Small Catechism, he offers some commentary on the Ten Commandments. His commentary on the eighth commandment is helpful. The commandment reads simply, like this:

“Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor.”Like the other commandments I’ve mentioned, it is only a few words long. And like those others, it leaves room for commentary. Luther’s commentary does something that I find very helpful. While the commandment is negative (“thou shalt not,” it says) Luther thought that alongside each negative commandment was something positive. So he writes:

What does this mean?--Answer. We should fear and love God that we may not deceitfully belie, betray, slander, or defame our neighbor, but defend him, [think and] speak well of him, and put the best construction on everything.”This is akin to what Plato offers in several ways in his Republic, and to Ulpian’s legal principle of “giving to each person their due,” (see note, below) but it goes a little further, with an agapic tinge: Luther doesn’t just tell us not to lie, nor does he tell us to be simply honest, but to put the best construction on everything.

This is hard.

“A Mutual, Joint-Stock World, In All Meridians”

It’s especially hard when we feel that others are getting ahead of us, and that we are in a competition with everyone else. If the world is a zero-sum game, then everyone run, and the Devil take the hindmost. But what if Queequeg is right? When Queequeg sees a fellow sailor drowning and no one moves to save the sailor, Queequeg leaps into the water to save his fellow. There is no question of whether they are of the same tribe, the same party, the same race, the same team. Queequeg is, as far as anyone aboard the ship knows, a cannibal. And yet the narrator, observing Queequeg’s agapic care for his fellow sailor, offers this comment:

Was there ever such unconsciousness? He did not seem to think that he at all deserved a medal from the Humane and Magnanimous Societies. He only asked for water—fresh water—something to wipe the brine off; that done, he put on dry clothes, lighted his pipe, and leaning against the bulwarks, and mildly eyeing those around him, seemed to be saying to himself—“It’s a mutual, joint-stock world, in all meridians. We cannibals must help these Christians.” -- Herman Melville, Moby Dick. (New York: Signet, 1980) 76

It’s much easier to approach theological conversations with the idea that our theology is a weapon and that our enemies are those with whom we disagree. It’s so easy to forget what Saint Paul wrote, that we don’t fight against flesh and blood, but against far less tangible, invisible forces that would have us view our neighbors with malice.

Could we approach theology the way Queequeg approaches the plight of his fellow sailor? Is it possible to maintain one’s cherished beliefs while recognizing that one’s object of “ultimate concern” might be something we don’t yet see with certainty and clarity? I cannot speak for others, so I’ll just offer this confession: I’m aware of a capacity in myself to care more for my theology than for the God that my theology claims to describe. In simpler terms: my own theology can become so dear to me that it becomes an idol, displacing the very God I set out to love and serve. And how to I love and serve my God? So far, the best I can offer you is this: I should love God with all I am, and I should love my neighbor as myself. Does that seem unclear to you? It does to me. Which means I need all the help I can get in clarifying my vision. Right now I see in a glass, darkly.

The philosopher Jonathan Lear suggests a principle akin to Queequeg’s, and to Luther’s: the principle of humanity. He describes it like this:

“The interpretation thus fits what philosophers call the principle of humanity: that we should try to interpret others as saying something true—guided by our own sense of what is true and of what they could reasonably believe.” -- Jonathan Lear, Radical Hope. 4 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006) (See note below)The Episcopal Church’s Book of Common Prayer offers another commentary on the fourth commandment, the commandment not to take the name of God in vain. The Book of Common Prayer rephrases the commandment like this:

You shall not invoke with malice the Name of the Lord your God.

Amen. Lord have mercy.The rephrasing is a commentary on “in vain.” Invoking God’s name in vain is equated with invoking it with malice, that is, with the opposite of agapic love.

Conclusion

It’s appropriate to me that I teach this course in Lent each year. Lent is a good time for self-examination, and that includes an examination of all kinds of pieties and supposed certainties. What is it that we hold to be of ultimate concern? What do we love with all our heart, soul, mind, and strength? That might just be playing the role of a god in our lives. If so, does that God help us to love our neighbors as ourselves?

I could be wrong in all I say in this class. I enter it with “fear and trembling,” knowing that there’s so much I don’t know, and knowing that many of my students might be wiser than I am. I know they might have seen the divine far more clearly than I ever will in this life.

But oh, how I want them to live well, not to be entangled by anxious grief, not to be afraid of the future, not to be burdened by relentless suspicions and fears.

Yes, there are other subjects I could teach, and yes, there are other jobs I could do. But for me, right now, this one feels like a good way to reexamine my own ultimate concerns, and a good way to help others to do the same. May I do so without malice, with agapic love, and with the constant practice of putting the best construction on everything.

Amen. Lord, have mercy.

*****

Notes:

* Scott Russell Sanders: I'm thinking of his essay, "The Warehouse and the Wilderness," and in particular the opening pages of that essay. You can find it in A Conservationist Manifesto, beginning on page 71. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009)

* Ulpian's words are cited in Justinian, Institutes, Book 1, Title 1, Sec. 3.

* Lear has an endnote at the end of this sentence. It reads: “This principle is also known as the ‘principle of charity,’ and the most famous arguments for it are given by Donald Davidson. See his “Radical Interpretation,” in Inquiries Into Truth And Interpretation (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984), pp. 136-137; “Belief and the Basis of Meaning,” ibid., pp. 152-153; “Thought and Talk,” ibid., pp. 168-169; “On the Very Idea of a Conceptual Scheme,” ibid., pp. 196-197; “The Method of Truth in Metaphysics,” ibid., pp. 200-201.”

A Short Story: Mercy

When we left the Earth we thought we had escaped. We were the wealthiest people on the planet, and we had access to the best technology in history. People were willing to do whatever we wanted because we paid well.

We planned a thousand-year trip, a one-way flight to another home. We made arrangements for terraforming ships to arrive a little more than a century before we would, and we took the slow route so that the world would have time to get started before we got there. We knew it would be hard, that after a long sleep we’d wake up to colonize uninhabited territory. We knew there was real risk, but we also knew that the risk on earth was growing with the population. We wanted a new life for ourselves and for our children. We were young, and healthy, and strong.

What we did not count on was the way technology would change. We thought we were leaving a dying world, and we were. As we left the planet the trail of smoke from our burning fuel was our last goodbye, our last contribution to an increasingly unbreathable atmosphere. We meant no harm, but we had to burn some fuel to escape gravity.

Who knew that when we left, the world we left behind would undergo such changes? The population collapse that we expected took place, and we were lucky to escape before it did. That much we foresaw. But we did not think anyone would survive long after we left. When the population decreased, the air and the water started to clean themselves up, at least a little, and the people who made it through that first year of suffering came out of it stronger and more committed to never letting in happen again. They moved more slowly and more carefully than we did. They focused their energies on cleaning up the mess we left behind. And they were pretty good at it, but not good enough. Some of what they did allowed them to survive another few decades, but they saw that the damage was done and the planet was not a place they could stay for long. So they came up with a new plan, to help not just a few people but the whole surviving population of earth to head to the only known survivable exoplanet, one that had been discovered by our investments, and that was already on its way towards being terraformed. They headed for the same planet we had already claimed for our own.

And they arranged to get here first.

I’m writing this while my husband is on the radio, talking with the military patrol that was waiting for us. They say we cannot come down to the surface, and I am trying to hold back my tears. We worked so hard for this, we bought this, we sacrificed everything we had for this, and now they are refusing us entry. They knew we were coming, and they have been waiting for us.

How can they do this to us? We’re the same people, the same species! Humans are nowhere else in the universe. There is no other home for us. The place we all left is uninhabitable, but now they are telling us that we must turn away. I don’t know what this will mean. Do they want us to go back? We cannot; nothing is there waiting for us. Have they found a new place for us to go? My husband has shushed me. The military officer is saying they do not know of other planets. Why are we not allowed here? Why can we not land on the other side of the planet? I know, I’m sorry. I’ll keep it down.

We are traitors, they say. We left them in their time of need, and we left destruction in our wake. They don’t trust us, and they will not let us land. Hasn’t enough time gone by? Can’t we bury the hatchet? Why won’t they forgive us? What are we going to do?

They say they will refuel us. This is their idea of kindness. We are being given enough fuel and supplies to return to Earth. Another millennium of sleep, and perhaps the Earth we left will welcome us home, they say, but we are not welcome here.

My husband is angry. He says that when our ship is refueled he plans to crash it into their city below. They say that they will stop us. They have boarded our ship and sedated my husband. They are about to sedate me, but they are letting me write this last sentence so that when we get back to Earth we will remember their mercy.

Copyright November 10, 2018 David L. O'Hara

How I Write - A Quick Reply To A Young Writer

The email I received was polite and kind, and I thought it worth my time to write a short reply even though I had other urgent tasks to get to. I never want to let the truly important abdicate to the merely urgent; tasks that clamor are not always the best tasks, and those opportunities that speak softly are not always the least valuable. Here's the email I received, and my reply. I've edited the email I received to protect the author's privacy and to highlight their question and some of my main points in boldface. I've edited my reply slightly as well, since I've got a few minutes to do so.

If you've got good advice for my correspondent, feel free to offer your advice in the comments below. (I'll delete advertisements, though.)

Dr. O'Hara,

I'm emailing you on a rather odd premise. I am a second-year student [in] college, and an avid follower of yours on Twitter. Over the course of about six months I have admired your work from afar. I would like to say your passion not only for your students, but your work, is nothing less than inspiring. That being said -- without taking up too much of your time -- I would like to ask for your advice. I know that you have written and contributed to many books. I have started one of my own, and would like to know how you go about the process of writing? I know it is a rather vague question, but I am just getting to about seven thousand words and fifty plus seems daunting. Do you have any advice?

Again, I am sure you are a very busy man and if this isn't something you have time to entertain I wholeheartedly understand.

Thank you for your time!

[Signature]

Dear Friend,

Thanks for your thoughtful question. I'm not sure I've got a one-size-fits-all process, but I'm happy to share what I've learned and what I do. I've only got time for a short reply this morning, so apologies in advance for the brevity of this note. I have some students coming by in a few minutes and I like to try to be present for those who are right in front of me as much as possible. I suppose it's sort of a spiritual practice for me, that "being present." The alternative (for me, anyway) is to spend too much of my time not being present, which usually takes the form of stress and anxiety about that which is geographically or chronologically distant. Anyway, while my students aren't here, I'm regarding this email from you as your "presence" in my office, so let's talk about writing...

...which I suppose we've already begun doing. For me, one of the most helpful things has been making sure not to regard writing as an optional exercise. (It's too easy for me to let the urgent crowd out the important.) Writing matters to me because it helps me to think and it helps me to be in conversation with others. If I don't give it at least a little of my time - on a regular basis, that is - then my ability to write begins to atrophy. Disciplines that matter - the ones that are most connected to our best loves - should be treated like respiration; they need to be regular and constant. If writing is a matter of loving your neighbor for you, then write regularly, just like you breathe regularly.

Of course, the metaphor breaks down, because we breathe involuntarily and always, whereas we only write occasionally. But it's at least a partly useful metaphor. Because I want to be ready to write, I keep a paper notebook in my pocket all the time, remembering the words from one of the Narnia stories (Prince Caspian, maybe?) Hmm. Let's see. Yes, here it is:

“Have you pen and ink, Master Doctor?”“A scholar is never without them, your Majesty,” answered Doctor Cornelius.

– C.S. Lewis, Prince Caspian, ch. 13

Yes, it was Prince Caspian. And here's one of my other tricks: I write after each book I read. With each book, I take time to jot down a few words and a few lines that really mattered to me in that book. Then, when I want quick access to those words, I've got them all in a single file on my computer, and I can search for the word "ink" or "scholar" and up comes this quote. My file of quotations from books is now 130 pages long. (Don't despair - I've been adding to it for 20 years!) It's a tremendous resource for writing, and it helps me to remember what I read and where I read it.

Two more quick things, since I've got to go:

1) My graduate school faculty told me that writing a 300-page dissertation seemed like a lot, but if I thought of it as a page a day for a year, it would seem much smaller, and much easier. They were right.

2) I find it helpful to write more than one thing at a time. I'll work on one thing for a while - maybe only a few minutes a day - and then I find my mind is tired of writing and thinking about that subject. So I will turn to another task, and I often find I have new energy. Oddly, I wrote my first book while I was also writing my dissertation. I'd write the doctoral thesis during the day, and then, at night, I'd write the book as a way of distracting my mind and relaxing. Now I find that if I'm working on only one thing I feel great stress. Will I finish it? What if I mess it up? These questions haunt me. But when I have many writing projects ongoing, I don't mind it very much if I run into a wall of writer's block on one of them. True story: I have written several books that I will likely never publish, and I have half-written hundreds of articles and books that I may never publish. But each one is still on my computer, and I often return to those half-written pieces to scavenge a few footnotes or paragraphs or choice words. The unfinished tasks aren't on the scrap heap; they're unpolished gems in my store-room just waiting to be set in a new piece of jewelry. I'm not ashamed of them even though I don't wear them in public; they're treasures even though most people will never see them.

I hope this helps. Keep at it! Writing has been a great source of food for my mind and a great nourishment to my convivial conversations as well. I hope you find it to be of similar benefit.

All good things,

Dave

P.S. Here are a few other things I've written about writing, and teaching writing, and the role of nature in teaching me how to write.

A Professor's Environmental Humanities Summer

Do you know how your professors spend their summers? In a few days I will shift from my summer work to the work you're more familiar with: my work in the classroom. As you and I prepare to make that shift, I thought you might appreciate a glimpse at what I've been up to this summer.

When I was a student I knew very little about my professors' lives outside of the classroom. They were people I saw for a few hours a week, and whom I rarely saw outside of lecture halls. Every now and then I'd see one in a grocery store or walking down the street, and it was a bit of a surprise to see them living ordinary lives. On the one hand, I think it's good thing to give my students space apart from professors. It is helpful to have some boundaries, after all. On the other hand, the way we live our lives can be part of our teaching. This is one of the advantages of study-travel courses, and it's why I invite you to come to my office for tea and not just for formal advising. I hope you will see helpful lessons (hopefully good ones!) in the way we professors choose to spend our time, and that those spontaneous and organic conversations will offer more food for thought than I have time to offer in formal lessons.

Other than the science professors who spend a lot of time doing lab research, you might think we professors are simply on vacation in the summer. In part, you're right: we have three main responsibilities as Augie professors: teaching, scholarship, and service. And most of us are on a nine- or ten-month contract; we've chosen a life that pays us less in money than we might make in other jobs, and in return, we have significantly more flexibility with our time. That's a nice tradeoff for most of us, and it's one of the delights of being part of an academy.While most of us do use some of that time for rest after working hard for an academic year, we also use the summer to catch up on our scholarship, to learn more, to find new resources that will help us to serve our community, and to prepare to be better teachers.

Since I teach a wide range of courses (in philosophy, classics, religion, environmental humanities, Ecology, study abroad, and more) my summer is usually spent in study. This summer was no exception. This isn't a complete list of what I did, but it'll give you the big picture anyway:

|

| One of the lycaenids I photographed in my garden this summer. Actually a very small butterfly, but some small things can give you a big picture nonetheless, if you know what to look for. |

After grading exams and Commencement, I started a week of meetings. The big picture: wrapping up the school year, and getting ready for the next. Meetings may not sound appealing, but we tend to get a lot done that makes the rest of the school year possible. This is also often a time when I get to meet with alumni, community leaders, and people who need my help with various projects. File this under "service," I suppose.

The first week: I taught a weeklong graduate class in philosophy for our Sports Administration and Leadership Master's program. This was an intensive 40-hour seminar on Plato's Republic and Augustine's Confessions. We discussed a number of things, like the roles of a leader; the difficulties of knowing anything with confidence and of making decisions when one doesn't know with certainty; and the important place of sports and playfulness in the ethical development of individuals and communities.