∞

When The Court Will Not Give Justice

“They suppressed their consciences and turned away their eyes from looking to Heaven or remembering their duty to administer justice.”

“Just as she was being led off to execution, God stirred up the holy spirit of a young lad named Daniel, and he shouted with a loud voice, ‘I want no part in shedding this woman’s blood!’ All the people turned to him and asked, ‘What is this you are saying?’ Taking his stand among hem he said, ‘Are you such fools, O Israelites, as to condemn a daughter of Israel without examination and without learning the facts? Return to court, for these men have given false evidence against her.’”

-- The Book of Susanna, v. 9. (New Revised Standard Version)

“Just as she was being led off to execution, God stirred up the holy spirit of a young lad named Daniel, and he shouted with a loud voice, ‘I want no part in shedding this woman’s blood!’ All the people turned to him and asked, ‘What is this you are saying?’ Taking his stand among hem he said, ‘Are you such fools, O Israelites, as to condemn a daughter of Israel without examination and without learning the facts? Return to court, for these men have given false evidence against her.’”

-- The Book of Susanna, vv. 45-49. (New Revised Standard Version)

∞

Of Men and of Angels

"If I speak with the tongues of men and of angels, but I have not love, then I have become a resounding gong or a clanging cymbal."

That's from one of St. Paul's letters to the church in Corinth. It's a passage often read at weddings, probably because it speaks eloquently about agapic love.

I like it for another reason: it has a nice onomatopoeic pun in the Greek text. Paul's "If I speak..." is lalo; his "clanging" is alaladzon, which sounds like the noise a gong makes and sounds like it could mean "un-speaking." (In Greek, words that begin with "a-" are often like English words beginning with "un-".)

This week, as we approach the third Sunday in Advent, I was looking again at a poem I wrote during this week a few years ago, after the school shooting in Newtown. In it I compared first responders and teachers and others who give up so much for the sake of the common good to angels. That is my second-most read post ever.

The most-read post is one I wrote after Ferguson, about the militarization of our first responders, and the way the tools we equip ourselves with change the way we interact with the world - and with other people.

Both of these posts are about public servants. Taken together they remind me that what is done in love can be heroic and life-giving, and what is done in fear can become tyrannical. They remind me that we have a tendency to revere the outward signs of badges and uniforms, when we should judge characters by the habits they embody and by the actions that show the habits.

And they remind me that we have a long, long way to go before we can say we have learned to love one another.

*****

I should add that even the title to this post is misleading. The word Paul uses is not "men" but "humans." I like the cadence of the old translation "men" but the word is anthropon, not andron. Normally I prefer the more inclusive (and more accurate) "humans" but I first learned this verse in an older, poetic translation and the rhythm of it has stuck with me.

That's from one of St. Paul's letters to the church in Corinth. It's a passage often read at weddings, probably because it speaks eloquently about agapic love.

I like it for another reason: it has a nice onomatopoeic pun in the Greek text. Paul's "If I speak..." is lalo; his "clanging" is alaladzon, which sounds like the noise a gong makes and sounds like it could mean "un-speaking." (In Greek, words that begin with "a-" are often like English words beginning with "un-".)

This week, as we approach the third Sunday in Advent, I was looking again at a poem I wrote during this week a few years ago, after the school shooting in Newtown. In it I compared first responders and teachers and others who give up so much for the sake of the common good to angels. That is my second-most read post ever.

The most-read post is one I wrote after Ferguson, about the militarization of our first responders, and the way the tools we equip ourselves with change the way we interact with the world - and with other people.

Both of these posts are about public servants. Taken together they remind me that what is done in love can be heroic and life-giving, and what is done in fear can become tyrannical. They remind me that we have a tendency to revere the outward signs of badges and uniforms, when we should judge characters by the habits they embody and by the actions that show the habits.

And they remind me that we have a long, long way to go before we can say we have learned to love one another.

*****

I should add that even the title to this post is misleading. The word Paul uses is not "men" but "humans." I like the cadence of the old translation "men" but the word is anthropon, not andron. Normally I prefer the more inclusive (and more accurate) "humans" but I first learned this verse in an older, poetic translation and the rhythm of it has stuck with me.

∞

Desmond Tutu On Descartes' Radical Individualism

"Ubuntu is very difficult to render into a Western language. It speaks of the very essence of being human....[If you have Ubuntu] then you are generous, you are hospitable, you are friendly and caring and compassionate. You share what you have. It is to say, 'My humanity is caught up, inextricably bound up, in yours.' We belong in a bundle of life. We say 'A person is a person through other persons.' It is not, 'I think, therefore I am.' It says rather: 'I am human because I belong. I participate, I share.'"

Desmond Tutu, No Future Without Forgiveness, 31. (New York: Random House, 2000)

∞

The Trivium And The Quadrivium

The Seven Liberal Arts (and their aims)

At some point in the Middle Ages, through a slow process of growth and refinement, educators came to identify seven arts that were considered liberal. The seven liberal arts were the arts practiced by people who were, or who would be, free. (The Latin word liber can mean "a free man.")

The liberal arts were divided into two groups: the trivium and the quadrivium. As the names suggest, the trivium included three arts, and the quadrivium included four.

The trivial arts sought to teach eloquentia, or eloquence, the proper use of words. The quadrivial arts aimed at sapientia, or sapience, the proper use of numbers.

In each case there is a natural progression, beginning with the rudiments and building on those foundations to help the student master eloquence and sapience.

The Trivium and the Quadrivium (and how they are built)

The trivium proceeds like this:

The quadrivium proceeds like this:

But Is Any Of This Relevant?

It's not hard to see that a lot of this is outdated, especially in the quadrivium, which was like the STEM of the Middle Ages, focusing on mathematics, engineering, and natural sciences. We no longer believe in the "music of the spheres" or that the motion of astronomical bodies is governed by harmony akin to music. And our sciences and humanities have grown to include many other disciplines that (at least at first) don't seem to be included here.

It's also not hard to see that some of the way we educate today still has echoes of this structure. For instance, until recently, we called children's schools "grammar schools," and this is why.We still consider it important to begin important enterprises with teaching the relevant vocabulary, grammar and logic: we often begin classes by introducing new vocabulary, and we begin contracts by defining terms.

And while we don't think of outer space as being a set of nested, harmonious spheres governed by intelligences who receive their direction from the Empyrean, we do think number is extremely important as a tool for discovering how nature works. This may seem like the most obvious of points, but that is because the idea has pervaded our thinking. It's a good idea, and it stuck. Similarly, we have the hunch that inquiry into the nature of things will in fact be met with answers. Again, this seems obvious, but not every culture has thought so. The idea has stuck, and it has paid off.

Yes, But Only If You Care About Science And Freedom.

In my view, the trivial arts and their organization remain as relevant as they once were, for three reasons.

First, every free person needs to know how words are used. If you don't learn to use them, and then practice with them, you will be easily misled. If you don't study persuasion, you are far less likely to know that you are being persuaded.

Second, and related to the first point, the sciences depend upon the trivial arts. Students who cannot read and write cannot learn effectively.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, long study in the humanities leads one to consider both the way words are used for persuasion and the ethics of persuasion. People who are trained in the conclusions of the sciences are not scientists, they are databanks. People who are trained in some of the methods of the sciences are technicians. Databanks and technicians are useful to other people. But what we need are people trained in the scientific method, which, by the way, is not something we get from the sciences. It is tested and approved by the sciences, but the natural sciences do not give it to us. Which of the natural sciences could discover a scientific method, after all? Scientific method is about the proper handling of data, the examination of claims and propositions, and the distribution of relevant conclusions. Look back at the description of the trivium and the quadrivium and you'll see that this is the work of the former, not of the latter.

The Real Crisis In The Humanities

There is a lot of talk these days about the crisis in the humanities. The money is all in the sciences, and smart students should go there to study, we are told. College administrations look to humanities departments as service departments to bolster the offerings of the science departments, who do the real work of the university.

I actually don't dispute this view, even though I'm in the humanities. It's quite obvious that much of the money is in the sciences, and I think that smart students should study the sciences. That's because I think every student should study the sciences.

But I also think that smart students should engage in long study of the humanities. The sciences depend upon the humanities, just as the quadrivium was legless without the trivium. More importantly, people who want to be free -- that is, people who do not wish to be persuaded without their consent, people who wish to think for themselves, people who wish to wield tools and not just to be the tools of others -- these people need to study the humanities.

The crisis in the humanities is that even in the humanities we've allowed ourselves to forget how interrelated all the disciplines are. It's time to brush up our eloquence, for the sake of our students, and take this message to our schools.

*****

Addendum: A friend wrote to me and pointed out that I called the second part of the Trivium "logic" when I should have named it "dialectic," which includes both logic and disputation. I don't dispute his correction.

I've also since discovered Dorothy Sayers' "The Lost Tools of Learning," an illuminating essay on the medieval liberal arts. I wrote this post hastily, after a meeting at my college where the question of what an education ought to do was under consideration. I wanted to make a thumbnail sketch of the Trivium and Quadrivium for my colleagues, and this was the result of some quick typing in the last few minutes of the workday. A fuller picture would have included C.S. Lewis' essay "Imagination and Thought in the Middle Ages," and at least some mention of Martianus Capella. Maybe another time I'll return to this topic and write that fuller essay. For now, these references will have to suffice.

At some point in the Middle Ages, through a slow process of growth and refinement, educators came to identify seven arts that were considered liberal. The seven liberal arts were the arts practiced by people who were, or who would be, free. (The Latin word liber can mean "a free man.")

The liberal arts were divided into two groups: the trivium and the quadrivium. As the names suggest, the trivium included three arts, and the quadrivium included four.

The trivial arts sought to teach eloquentia, or eloquence, the proper use of words. The quadrivial arts aimed at sapientia, or sapience, the proper use of numbers.

In each case there is a natural progression, beginning with the rudiments and building on those foundations to help the student master eloquence and sapience.

The Trivium and the Quadrivium (and how they are built)

The trivium proceeds like this:

- Grammar. This is the study of words, and especially:

- how definitions work, so that we can "come to terms" with one another; and

- how words are assembled into meaningful sentences or propositions.

- Logic. This is the study of the structure of arguments:

- how to assemble propositions into arguments; and

- how to draw proper conclusions from those propositions without error.

- Rhetoric. This is the study of the proper use of arguments:

- how to use arguments to persuade others; and

- how and when to persuade without misleading people.

The quadrivium proceeds like this:

- Arithmetic. This is the study of number.

- Geometry. This is the study of number in space.

- Music. This is the study of number in time.

- Astronomy. This is the study of number in space and time.

But Is Any Of This Relevant?

It's not hard to see that a lot of this is outdated, especially in the quadrivium, which was like the STEM of the Middle Ages, focusing on mathematics, engineering, and natural sciences. We no longer believe in the "music of the spheres" or that the motion of astronomical bodies is governed by harmony akin to music. And our sciences and humanities have grown to include many other disciplines that (at least at first) don't seem to be included here.

It's also not hard to see that some of the way we educate today still has echoes of this structure. For instance, until recently, we called children's schools "grammar schools," and this is why.We still consider it important to begin important enterprises with teaching the relevant vocabulary, grammar and logic: we often begin classes by introducing new vocabulary, and we begin contracts by defining terms.

And while we don't think of outer space as being a set of nested, harmonious spheres governed by intelligences who receive their direction from the Empyrean, we do think number is extremely important as a tool for discovering how nature works. This may seem like the most obvious of points, but that is because the idea has pervaded our thinking. It's a good idea, and it stuck. Similarly, we have the hunch that inquiry into the nature of things will in fact be met with answers. Again, this seems obvious, but not every culture has thought so. The idea has stuck, and it has paid off.

Yes, But Only If You Care About Science And Freedom.

In my view, the trivial arts and their organization remain as relevant as they once were, for three reasons.

First, every free person needs to know how words are used. If you don't learn to use them, and then practice with them, you will be easily misled. If you don't study persuasion, you are far less likely to know that you are being persuaded.

Second, and related to the first point, the sciences depend upon the trivial arts. Students who cannot read and write cannot learn effectively.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, long study in the humanities leads one to consider both the way words are used for persuasion and the ethics of persuasion. People who are trained in the conclusions of the sciences are not scientists, they are databanks. People who are trained in some of the methods of the sciences are technicians. Databanks and technicians are useful to other people. But what we need are people trained in the scientific method, which, by the way, is not something we get from the sciences. It is tested and approved by the sciences, but the natural sciences do not give it to us. Which of the natural sciences could discover a scientific method, after all? Scientific method is about the proper handling of data, the examination of claims and propositions, and the distribution of relevant conclusions. Look back at the description of the trivium and the quadrivium and you'll see that this is the work of the former, not of the latter.

The Real Crisis In The Humanities

There is a lot of talk these days about the crisis in the humanities. The money is all in the sciences, and smart students should go there to study, we are told. College administrations look to humanities departments as service departments to bolster the offerings of the science departments, who do the real work of the university.

I actually don't dispute this view, even though I'm in the humanities. It's quite obvious that much of the money is in the sciences, and I think that smart students should study the sciences. That's because I think every student should study the sciences.

But I also think that smart students should engage in long study of the humanities. The sciences depend upon the humanities, just as the quadrivium was legless without the trivium. More importantly, people who want to be free -- that is, people who do not wish to be persuaded without their consent, people who wish to think for themselves, people who wish to wield tools and not just to be the tools of others -- these people need to study the humanities.

The crisis in the humanities is that even in the humanities we've allowed ourselves to forget how interrelated all the disciplines are. It's time to brush up our eloquence, for the sake of our students, and take this message to our schools.

*****

Addendum: A friend wrote to me and pointed out that I called the second part of the Trivium "logic" when I should have named it "dialectic," which includes both logic and disputation. I don't dispute his correction.

I've also since discovered Dorothy Sayers' "The Lost Tools of Learning," an illuminating essay on the medieval liberal arts. I wrote this post hastily, after a meeting at my college where the question of what an education ought to do was under consideration. I wanted to make a thumbnail sketch of the Trivium and Quadrivium for my colleagues, and this was the result of some quick typing in the last few minutes of the workday. A fuller picture would have included C.S. Lewis' essay "Imagination and Thought in the Middle Ages," and at least some mention of Martianus Capella. Maybe another time I'll return to this topic and write that fuller essay. For now, these references will have to suffice.

∞

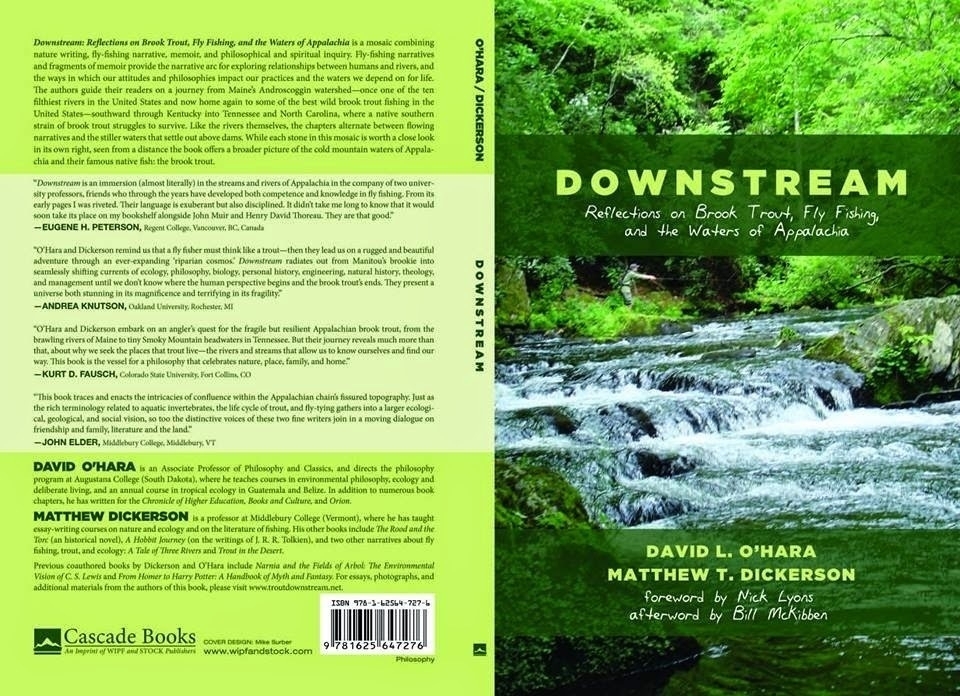

Downstream: Reflections on Brook Trout, Fly Fishing, and the Waters of Appalachia.

Downstream: Reflections on Brook Trout, Fly Fishing, and the Waters of Appalachia.

(On brook trout, ecology, and love. Wipf and Stock, (Cascade Press) 2014)

Foreword by Nick Lyons

Afterword by Bill McKibben.

Narnia And The Fields Of Arbol

(On the environmental vision of C.S. Lewis. University Press of Kentucky, 2008)

From Homer To Harry Potter

(On myth, fantasy, and religion. Brazos Press, 2006)

Books

Downstream: Reflections on Brook Trout, Fly Fishing, and the Waters of Appalachia.

Downstream: Reflections on Brook Trout, Fly Fishing, and the Waters of Appalachia. (On brook trout, ecology, and love. Wipf and Stock, (Cascade Press) 2014)

Foreword by Nick Lyons

Afterword by Bill McKibben.

Narnia And The Fields Of Arbol

(On the environmental vision of C.S. Lewis. University Press of Kentucky, 2008)

From Homer To Harry Potter

(On myth, fantasy, and religion. Brazos Press, 2006)

∞

Entertaining Angels

Here's my latest contribution to the Sojourners blog, a reflection on a beggar I met in Paris 25 years ago, and on what that might mean for me today.

Here's an excerpt:

Here's an excerpt:

You just never know. There’s no way to know, just from looking at the sign. Maybe he was a con man, or maybe he was just my brother, genuinely in need of human contact to maintain his dignity. Or maybe he was even more than that. How does that passage go? “Some of you have entertained angels unawares.”You can read the rest of it here.

∞

Camping With My Students: Stargazing in the Badlands

Around two in the morning I awoke to the song of coyotes. I opened my eyes and looked up just in time to see a green meteor arc across the sky. I was camping outdoors, with my students, in a remote corner of South Dakota. Welcome to one of my favorite classrooms.

Each fall I look for an ideal weekend to take my Ancient and Medieval Philosophy students stargazing. An ideal weekend counts as one where we will have clear skies, a new moon, and reasonably warm weather so we can spend a lot of time outside.

Several times over the last ten years, the weather's been so good that we've been able to go out to a primitive campground (i.e. one where there is no electricity and almost no urban glow) in the Badlands National Park.

On such nights, in such places, the sky glistens with stars. The Milky Way is a bright band across the night, and meteors punctuate our views each hour.

I tell my students that this is an optional trip. They don't get credit for coming, and they don't lose any credit for staying home. It's a four-hour drive from our campus, so it's a real commitment of time on their part. Their only rewards are these: an experience of what the Norwegians call friluftsliv, a beautiful night under the stars in a remote and lovely place, and free pancakes at sunrise, cooked by me.

And yet every time I offer this trip, half a dozen or more students - and sometimes other professors - tag along.

I've written before about the importance of teaching outdoors and of doing labs in philosophy. Experientia docet, experience teaches us. What we learn through lived, full-bodied experience tends to stick with us far better than what we simply hear spoken from a lectern or see on a PowerPoint slide.

We go out there, ostensibly, to see the stars. This is because I want my students to watch the skies and to imagine what it would have been like for ancient and medieval philosophers like Thales, Plutarch, Ptolemy, Eratosthenes and, even Galileo (on the cusp of the Middle Ages) to gaze at the skies and learn from their movements.

But we are really there for other reasons that are easier to show than to tell. I want them to see that ideas do not grow up in a vacuum, and that the artificial divisions between academic disciplines are really artificial and convenient. Educated people should care about all the disciplines. We should not allow them to be compartmentalized, as though philosophy and sociology had nothing to do with accounting, or physics, or poetry.

Aristotle tells us that the love of wisdom begins in wonder. I will add that experience of new things can be the beginning of wonder.

Many of my students have never heard coyotes sing. In the Badlands, they trot past our cots and tents and sing to us all night long. When we wake in the morning, we are often surrounded by small groups of bison, slowly grazing their way along the hillsides. After breakfast we climb the steep slopes and find ancient fossils.

I don't know if any of this is a desirable or assessable outcome for a philosophy class. Also, I don't care. Because all of these things are, I think, desirable outcomes for life.

Because I believe that "it is beautiful to do so" is reason enough to sleep under the stars.

|

| We set up tents, but we rarely use them. Much nicer to sleep under the stars. |

Each fall I look for an ideal weekend to take my Ancient and Medieval Philosophy students stargazing. An ideal weekend counts as one where we will have clear skies, a new moon, and reasonably warm weather so we can spend a lot of time outside.

Several times over the last ten years, the weather's been so good that we've been able to go out to a primitive campground (i.e. one where there is no electricity and almost no urban glow) in the Badlands National Park.

On such nights, in such places, the sky glistens with stars. The Milky Way is a bright band across the night, and meteors punctuate our views each hour.

I tell my students that this is an optional trip. They don't get credit for coming, and they don't lose any credit for staying home. It's a four-hour drive from our campus, so it's a real commitment of time on their part. Their only rewards are these: an experience of what the Norwegians call friluftsliv, a beautiful night under the stars in a remote and lovely place, and free pancakes at sunrise, cooked by me.

And yet every time I offer this trip, half a dozen or more students - and sometimes other professors - tag along.

|

| The stop sign is just a scratching post to this bison. |

I've written before about the importance of teaching outdoors and of doing labs in philosophy. Experientia docet, experience teaches us. What we learn through lived, full-bodied experience tends to stick with us far better than what we simply hear spoken from a lectern or see on a PowerPoint slide.

We go out there, ostensibly, to see the stars. This is because I want my students to watch the skies and to imagine what it would have been like for ancient and medieval philosophers like Thales, Plutarch, Ptolemy, Eratosthenes and, even Galileo (on the cusp of the Middle Ages) to gaze at the skies and learn from their movements.

But we are really there for other reasons that are easier to show than to tell. I want them to see that ideas do not grow up in a vacuum, and that the artificial divisions between academic disciplines are really artificial and convenient. Educated people should care about all the disciplines. We should not allow them to be compartmentalized, as though philosophy and sociology had nothing to do with accounting, or physics, or poetry.

Aristotle tells us that the love of wisdom begins in wonder. I will add that experience of new things can be the beginning of wonder.

Many of my students have never heard coyotes sing. In the Badlands, they trot past our cots and tents and sing to us all night long. When we wake in the morning, we are often surrounded by small groups of bison, slowly grazing their way along the hillsides. After breakfast we climb the steep slopes and find ancient fossils.

I don't know if any of this is a desirable or assessable outcome for a philosophy class. Also, I don't care. Because all of these things are, I think, desirable outcomes for life.

Because I believe that "it is beautiful to do so" is reason enough to sleep under the stars.

∞

How To Write Term Papers

Some thoughts while grading essays:

1) Write simply.

2) Deleteany unnecessary words that you don't need.

3) Use short words. This isn't the SAT or ACT vocabulary quiz, it's an essay. Make it readable. Don't try to wow anyone with big words. Big words are a distraction in ordinary writing. Save them for when you need them.

4) Write short sentences. As your sentences increase in length, the number of things that can go wrong in the sentences increases.

5) Bad writing is like a food stain on your shirt. No matter how good your ideas, the stain and the errors will make the strongest impression.

6) Know your point, and make your case. If you don't have a point, you're not writing a paper; you're just writing words. When you've got a point to make, state it plainly. Then help others see why they might agree with you.

7) Avoid sweeping generalizations. Go ahead and be bold in your essays, by all means. Try out strong ideas. But be clear about exactly which ideas you are presenting, and why. Avoid saying things like "since the beginning of time, this has been the case." Rather, say "this has been the case at least since 1641 when Descartes published his Meditations."

8) Edit. Then edit again. Don't think of proofreading as giving your writing a once-over before handing it in. Read what you've written, then read it again and again. Does each sentence lead into the next? Does each paragraph follow smoothly from what came before it? Is your opening line clear and compelling?

9) Love your reader. Try to put yourself in your readers' shoes. One helpful way to do this is to ask a friend to read your writing aloud to you. Listen for where they stumble or hesitate. Those are probably times where your writing is not clear.

10) Make writing a habit, not something you only do when you must. Like any other skill, the more you do it, the easier it becomes.

*****

P.S. I've edited this post. Even after you write something, go back and read it again and keep editing. It's good exercise.

1) Write simply.

2) Delete

3) Use short words. This isn't the SAT or ACT vocabulary quiz, it's an essay. Make it readable. Don't try to wow anyone with big words. Big words are a distraction in ordinary writing. Save them for when you need them.

4) Write short sentences. As your sentences increase in length, the number of things that can go wrong in the sentences increases.

5) Bad writing is like a food stain on your shirt. No matter how good your ideas, the stain and the errors will make the strongest impression.

6) Know your point, and make your case. If you don't have a point, you're not writing a paper; you're just writing words. When you've got a point to make, state it plainly. Then help others see why they might agree with you.

7) Avoid sweeping generalizations. Go ahead and be bold in your essays, by all means. Try out strong ideas. But be clear about exactly which ideas you are presenting, and why. Avoid saying things like "since the beginning of time, this has been the case." Rather, say "this has been the case at least since 1641 when Descartes published his Meditations."

8) Edit. Then edit again. Don't think of proofreading as giving your writing a once-over before handing it in. Read what you've written, then read it again and again. Does each sentence lead into the next? Does each paragraph follow smoothly from what came before it? Is your opening line clear and compelling?

9) Love your reader. Try to put yourself in your readers' shoes. One helpful way to do this is to ask a friend to read your writing aloud to you. Listen for where they stumble or hesitate. Those are probably times where your writing is not clear.

10) Make writing a habit, not something you only do when you must. Like any other skill, the more you do it, the easier it becomes.

*****

P.S. I've edited this post. Even after you write something, go back and read it again and keep editing. It's good exercise.

∞

An Early Christian Philosopher on Civil Disobedience

"There is never an obligation to be obedient to orders which it would be pernicious to obey."

-- St. Augustine, _Confessions_, I.vii. (Henry Chadwick trans.)

∞

Socratic Pragmatism: On Our Attitude Towards Inquiry

"I do not insist that my argument is right in all other respects, but I would contend at all costs in both word and deed as far as I could that we will be better men, braver and less idle, if we believe that one must search for the things one does not know, rather than if we believe that it is not possible to find out what we do not know and that we must not look for it."

Socrates, in Plato’s Meno, 86b-. G.M.A. Grube, trans.

∞

Wendell Berry: Past A Certain Scale, There Is No Dissent From Technological Choice

“But past a certain scale, as C.S. Lewis wrote, the person who makes a technological choice does not choose for himself alone, but for others; past a certain scale he chooses for all others. If the effects are lasting enough, he chooses for the future. He makes, then, a choice that can neither be chosen against nor unchosen. Past a certain scale, there is no dissent from technological choice.”

-- Wendell Berry, “A Promise Made In Love, Awe, And Fear,” in Moral Ground: Ethical Action For A Planet In Peril. Kathleen Dean Moore and Michael P. Nelson, eds. (San Antonio: Trinity University Press, 2010) p. 388.

∞

Interview on SD Public Radio

Karl Gehrke interviewed me on SD Public Radio today about my new book. We talk about the book, brook trout, fly-fishing, hunting, raising children, and a handful of other topics with occasional nods to Heidegger and Bugbee, Kathleen Dean Moore, Scott Russell Sanders, and, of course, Thoreau.

Click here to listen to the whole interview.

Click here to listen to the whole interview.

∞

Giving Our Prayers Feet

The American scientist and philosopher Charles Peirce described belief as an idea you are prepared to act on. If you say you believe something but you are not prepared to act on it, you probably don't really believe it in any meaningful sense of that word.

Of course, there might be a number of ways in which we might act on our beliefs.

What about prayer? Could praying be a kind of action?

It depends.

Philosopher and atheist Daniel Dennett once described prayer as a waste of time. I mean literally a waste of time. If you're praying, he said, you're not engaged in useful activity. When he was ill, someone offered to pray for him. His reply:

On the other hand, as I've argued before, prayer might be essential to other kinds of action.

Giving our money and time is generally a good thing, I think, but I think the giving becomes deeper still when we do as Thoreau urged in Walden: don't just give your money, but give yourself. In other words, if you've begun by dumping water on your head for an ALS icebucket challenge, great. Now deepen that giving by making it part of who you are.

If you decide to do that, prayer - or something like it, I don't care what you call it - can make a big difference. Here's what I mean: giving to charities can be automated, so you can do it without thinking about it. Set up an automatic bank transfer each month and you can give to as many charities as you can afford, without putting much of yourself in it. But if you make those philanthropies and missions the intentional object of your thought for part of each day, you might find that you begin to care a lot more about the cause and the people involved.

If praying is the act of giving some of your time to bring together the world's greatest needs and your greatest hopes, then prayer might be the most important thing we can do. Too often we allow ourselves to divorce others' needs from our hopes, and then the needs of others become allied with our fears.

This is one reason why I respond to the news each day with prayer. Sometimes my prayers are simply Kyrie eleison, "Lord, have mercy." Because sometimes that's all I've got when my heart and mind are overwhelmed. But if that's all I've got, then it will be my widow's mite, and I'll give it. By the way, this has the added effect of making me worry less without taking away my desire to act for goodness and justice.

(My friend Anna Madsen has a short, funny, and helpful piece about just that, by the way. Check it out here.)

All of this was inspired by a moving Facebook post by an alumnus of my college, Caleb Rupert. Caleb is a thoughtful and creative man, and though I don't know him well, he strikes me as a good egg and as someone who wants to do the best he can in this life. Here's what he shared on his page:

I asked Caleb if I could share his words here. His reply is just as good as his original post. He said I could post his words, provided I include some links to local food shelves, soup kitchens, and homeless shelters. I love that.

So I will ask that if you share this post, you do the same thing by posting a link to at least one organization in *your* community that helps the homeless. In that way, let us make our prayers effective to the best of our ability, and may they rise to whatever heaven may be.

Here are my links for Sioux Falls, South Dakota. Please consider volunteering your time, giving your money, and remembering them and the people they serve in your prayers. And as you do so, may your prayers grow feet, and begin to change the world.

The Banquet

Union Gospel Mission

St Francis House

Of course, there might be a number of ways in which we might act on our beliefs.

What about prayer? Could praying be a kind of action?

It depends.

Philosopher and atheist Daniel Dennett once described prayer as a waste of time. I mean literally a waste of time. If you're praying, he said, you're not engaged in useful activity. When he was ill, someone offered to pray for him. His reply:

Surely it does the world no harm if those who can honestly do so pray for me! No, I'm not at all sure about that. For one thing, if they really wanted to do something useful, they could devote their prayer time and energy to some pressing project that they can do something about. (emphasis added)I agree with him that if prayer keeps us from doing what we can to alleviate the suffering of the world, we're probably using our time poorly.

On the other hand, as I've argued before, prayer might be essential to other kinds of action.

Giving our money and time is generally a good thing, I think, but I think the giving becomes deeper still when we do as Thoreau urged in Walden: don't just give your money, but give yourself. In other words, if you've begun by dumping water on your head for an ALS icebucket challenge, great. Now deepen that giving by making it part of who you are.

If you decide to do that, prayer - or something like it, I don't care what you call it - can make a big difference. Here's what I mean: giving to charities can be automated, so you can do it without thinking about it. Set up an automatic bank transfer each month and you can give to as many charities as you can afford, without putting much of yourself in it. But if you make those philanthropies and missions the intentional object of your thought for part of each day, you might find that you begin to care a lot more about the cause and the people involved.

If praying is the act of giving some of your time to bring together the world's greatest needs and your greatest hopes, then prayer might be the most important thing we can do. Too often we allow ourselves to divorce others' needs from our hopes, and then the needs of others become allied with our fears.

This is one reason why I respond to the news each day with prayer. Sometimes my prayers are simply Kyrie eleison, "Lord, have mercy." Because sometimes that's all I've got when my heart and mind are overwhelmed. But if that's all I've got, then it will be my widow's mite, and I'll give it. By the way, this has the added effect of making me worry less without taking away my desire to act for goodness and justice.

(My friend Anna Madsen has a short, funny, and helpful piece about just that, by the way. Check it out here.)

All of this was inspired by a moving Facebook post by an alumnus of my college, Caleb Rupert. Caleb is a thoughtful and creative man, and though I don't know him well, he strikes me as a good egg and as someone who wants to do the best he can in this life. Here's what he shared on his page:

I'm standing at the bus stop and on the corner is a homeless woman. A kind looking black gentleman is walking by and nearly walks past her to beak the red-hand count down, 5, 4, 3....The gentleman stops, and turns to the homeless woman. He then falls to his knees and says a short prayer; I cannot hear the words, I'm too far away. As he finishes, she looks up and smiles at him. He smiles back and crosses the street. This gentleman gave up an entire two signals to acknowledge this woman through prayer. Though I do not believe that prayer will be heard by any entity other than the person praying and those around them, this does not discount the power, and importance, of acknowledgement of something as wicked as homelessness. A challenge in which so many of us like to ignore or pretend is non-existence, or worse, pretend this challenge is not as harsh and hard as it is. Regardless of my views of the validity of religion, I cannot ignore the importance of it being an entity which can cause those that follow, truly follow, not just "Sunday believers," but those that acknowledge the importance that every prophet and god-son has preached, which is to care for those that suffer and those that struggle. This gentleman, through his beliefs, gave this woman a smile, and the knowledge that when she goes to bed at night, someone is thinking about her and cares about her well being enough to stop and give his God, which he truly devotes himself to, a mention of her. In the end, regardless of a beliefs validity, what I believe is most important is relieving the pain of those that suffer and always remember that there is always someone who hurts more than you and your acknowledgement is the thing that can save them, even for a brief second, relief from that pain. (Emphasis added)Caleb's words remind me of Thoreau's, and of Dennett's, and of Jesus's. Yeah, you read that right. Because all four of them are concerned with making sure that whatever we do, we act on what we believe, and that we act in a way that tries to make others' lives better.

I asked Caleb if I could share his words here. His reply is just as good as his original post. He said I could post his words, provided I include some links to local food shelves, soup kitchens, and homeless shelters. I love that.

So I will ask that if you share this post, you do the same thing by posting a link to at least one organization in *your* community that helps the homeless. In that way, let us make our prayers effective to the best of our ability, and may they rise to whatever heaven may be.

Here are my links for Sioux Falls, South Dakota. Please consider volunteering your time, giving your money, and remembering them and the people they serve in your prayers. And as you do so, may your prayers grow feet, and begin to change the world.

The Banquet

Union Gospel Mission

St Francis House

∞

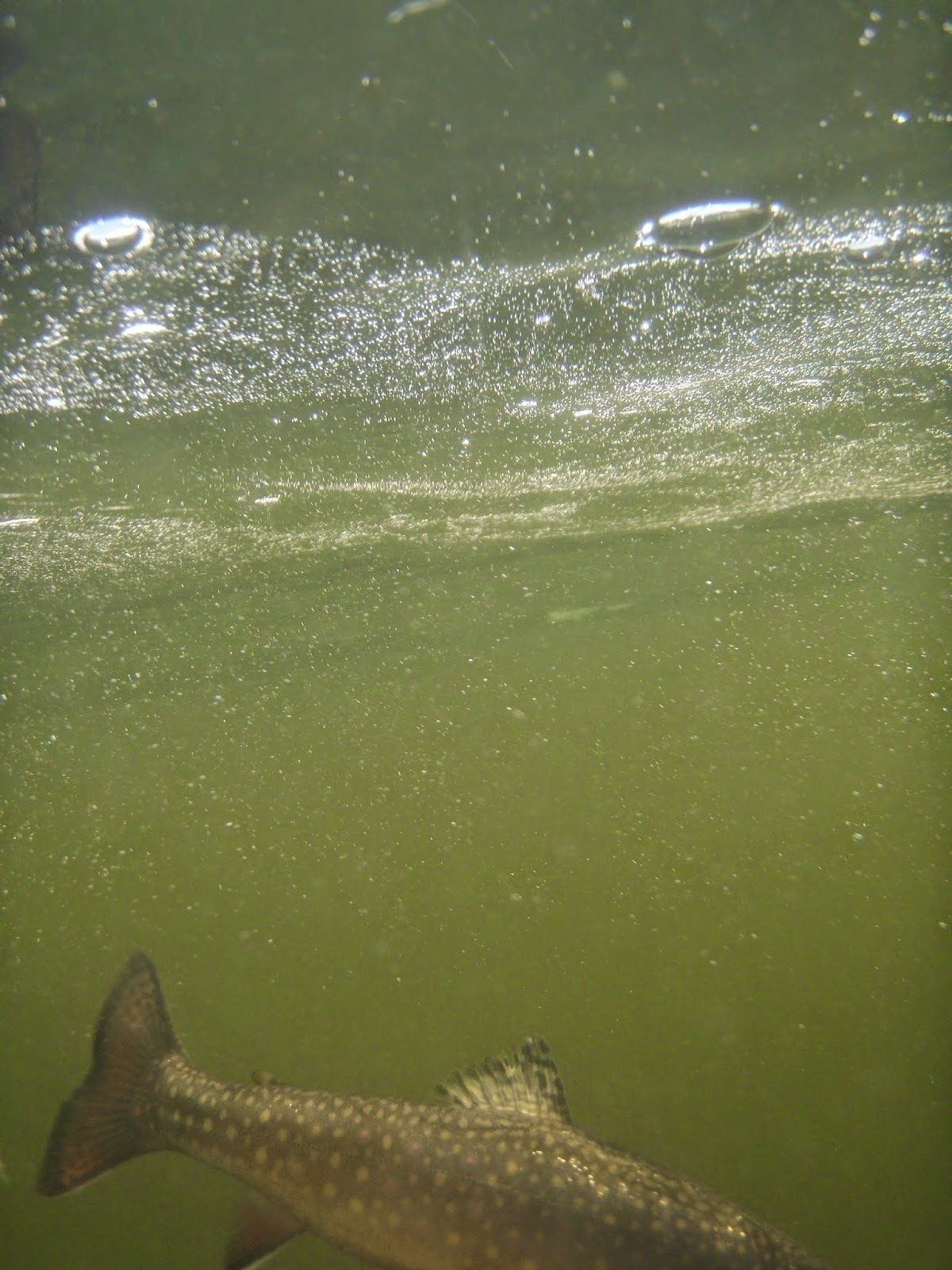

Dave Tabler has posted an excerpt from my new book (co-authored with Matthew Dickerson), Downstream, on his site, AppalachianHistory.net.

The passage is about the history of the Tellico River in eastern Tennessee. The Tellico was devastated a century ago by commercial logging. Attempts to restore the habitat and the indigenous wildlife have met with mixed results. The river still holds trout, but they are mostly western rainbow trout, not native brook trout. The rainbows, which are not native to the east coast or the Appalachians are simply easier to breed, which is what the state wants. Fish that are easy to breed are easy to stock, and stocked fish generate income.

You can read the passage here, and you can find the book here.

*****

I'm particularly happy with the photo here, because it's a photo of a free brook trout, one that is not attached to anyone's line, swimming away from me. It's hard to get such shots, but free-swimming brook trout really make me happy.

From My New Book: Brook Trout In The Tellico River

|

| Brook trout |

The passage is about the history of the Tellico River in eastern Tennessee. The Tellico was devastated a century ago by commercial logging. Attempts to restore the habitat and the indigenous wildlife have met with mixed results. The river still holds trout, but they are mostly western rainbow trout, not native brook trout. The rainbows, which are not native to the east coast or the Appalachians are simply easier to breed, which is what the state wants. Fish that are easy to breed are easy to stock, and stocked fish generate income.

You can read the passage here, and you can find the book here.

*****

I'm particularly happy with the photo here, because it's a photo of a free brook trout, one that is not attached to anyone's line, swimming away from me. It's hard to get such shots, but free-swimming brook trout really make me happy.

∞

Why Does A Philosophy Professor Write About Trout?

My most recent book, Downstream, is about brook trout. People sometimes wonder: why on earth would a professor of philosophy and classics write about such things? Surely I should be writing about metaphysics, epistemology and ethics, right?

To this question I have three brief replies, which I'll say more about later.

The first is that this book really is about those things, even if it won't appear to be so at first blush.

The second is that in fact, I think more philosophers should turn our attention to the matter of lived experience, to our technology, to our tools, and to our ways of knowing the world. It's not enough to know things about the world; we ought to ask just how we know the things we know, and how our tools and our very modes of life and habits affect that knowledge. And everything that hangs on that knowledge.

And for my third brief reply, I turn to Edward Mooney, who, in his introduction to Henry Bugbee's beautiful book, The Inward Morning, recalls a question Martin Heidegger asked Bugbee in August of 1955: “What occasion prompts philosophical reflection?”

Mooney writes that no doubt Heidegger “anticipated a flat American response. Yet he found his question returned in a Socratic reversal. Bugbee simply asked, echoing a Basho haiku, 'Could the sound of a fish leaping at a fly at dawn suffice?'”

To this question I have three brief replies, which I'll say more about later.

The first is that this book really is about those things, even if it won't appear to be so at first blush.

The second is that in fact, I think more philosophers should turn our attention to the matter of lived experience, to our technology, to our tools, and to our ways of knowing the world. It's not enough to know things about the world; we ought to ask just how we know the things we know, and how our tools and our very modes of life and habits affect that knowledge. And everything that hangs on that knowledge.

And for my third brief reply, I turn to Edward Mooney, who, in his introduction to Henry Bugbee's beautiful book, The Inward Morning, recalls a question Martin Heidegger asked Bugbee in August of 1955: “What occasion prompts philosophical reflection?”

Mooney writes that no doubt Heidegger “anticipated a flat American response. Yet he found his question returned in a Socratic reversal. Bugbee simply asked, echoing a Basho haiku, 'Could the sound of a fish leaping at a fly at dawn suffice?'”

*****

(Quotations taken from Mooney’s introduction to

Bugbee’s The Inward Morning, (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1999)

pp. xi-xii.

∞

The Tools That Hold Us

If you equip your police with military tools, it should not surprise you to find that the police begin to regard the problems they face as problems best solved with military tools. This is because tools are not inert. We think we hold the tools and wield them, but we should remember that they hold us, too.

In one of his notebooks the Puritan Jonathan Edwards observed that “If we hold a staff in our hand we seem to feel in the staff.” [1] He was noticing that we are less aware of the wood in our hand than of the gravel on the path when it connects with the staff.

To put it differently, the things we hold become extensions of ourselves. In a way, our tools make new knowledge possible. We should remember, though, that every awareness comes at the price of other awarenesses. When you peer through a telescope you can see what is distant at the expense of seeing what is near at hand. Holding a staff means not having a free hand to touch the lamb's ear and feel its softness.

Michael Polanyi, in his book Personal Knowledge, says it like this:

So with the police: when our tools are tools designed to give us mastery over others, we find ourselves becoming habituated to wielding that mastery, and regarding everyone who challenges that mastery as a natural slave.

In the face of this presumed mastery, the resentment of the mastered is not at all surprising.

Evan Selinger wrote insightfully about the way tools of mastery like guns affect us in an article in The Atlantic a few years ago. I was especially struck by a line he cited from Bruno Latour:

So if you give your police armor and military weapons, it should not surprise you if they begin to regard themselves as engaging in military activity. And it similarly should not surprise the police when the unarmed, un-armored populace feels that the police is not acting "to serve and protect" but quite the opposite.

I don't mean to exonerate anyone by these words, but to try to explain why right now there appears to be a growing hostility between the police and civilians. Police have a very hard job to do. Police officers I know have described long hours of dealing with people at their very worst, day after day. I'm impressed by how many police manage to keep calm and help to defuse potentially explosive situations, and do so repeatedly, every day on the job. And as more Americans own and carry handguns, it does not surprise me that many officers now wear bulletproof vests. They never know who might fire a foolish and angry shot, and they want to return to their families at the end of the day, alive and intact. That's not hard to understand.

But all of us face a hard choice. As I've argued before, we need good laws, and we need to maintain and enforce those laws. However, enforcement should not primarily mean the use of force, but a well-working judicial system, supported by good schools and watched over by excellent journalism. And we need one thing more: we need to become better people, to enact and inhabit the virtues we most wish to see in others. Intentional actions are like tools; as we dwell in them, they become the way we know the world, and, just as we hold on to them, they hold on to us.

This is what we should encourage in ourselves and in others. Not more and stronger weapons but better lives, lived nakedly and as unprotected from others as we dare. The armor we put on becomes the wall that divides us, and it becomes the lens through which we see some things, and because of which other things - like the humanity of our neighbors - becomes wholly invisible.

[1] Jonathan Edwards, The Works of Jonathan Edwards: Scientific and Philosophical Writings. Wallace E. Anderson, ed., (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1980) p.225

[2] Michael Polanyi, Personal Knowledge. 59.

[3] Walker Percy, The Moviegoer. (New York: Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, 1969) 232.

In one of his notebooks the Puritan Jonathan Edwards observed that “If we hold a staff in our hand we seem to feel in the staff.” [1] He was noticing that we are less aware of the wood in our hand than of the gravel on the path when it connects with the staff.

To put it differently, the things we hold become extensions of ourselves. In a way, our tools make new knowledge possible. We should remember, though, that every awareness comes at the price of other awarenesses. When you peer through a telescope you can see what is distant at the expense of seeing what is near at hand. Holding a staff means not having a free hand to touch the lamb's ear and feel its softness.

Michael Polanyi, in his book Personal Knowledge, says it like this:

“Our subsidiary awareness of tools and probes can be regarded now as the act of making them form a part of our own body. The way we use a hammer or a blind man uses his stick, shows in fact that in both cases we shift outwards the points at which we make contact with the things that we observe as objects outside ourselves. While we rely on a tool or a probe, these are not handled as external objects….We pour ourselves out into them and assimilate them as parts of our own existence. We accept them existentially by dwelling in them.” [2]They're not the only ones to notice this. I recall a passage in Walker Percy, where Binx describes his fiancée, Kate, at the wheel of her car. She practically dwells in her car, and it is as though the two have become one.

“When she drives, head ducked down, hands placed symmetrically on the wheel, the pale underflesh of her arms trembling slightly, her paraphernalia—straw seat, Kleenex dispenser, magnetic tray for cigarettes—all set in order about her, it is easy to believe that the light stiff little car has become gradually transformed by its owner until it is hers herself in its every nut and bolt.”Everyone who has a favorite tool knows this. We learn to touch-type through repetition. Practice may not make perfect, but it makes us so familiar that we find ourselves regarding our oldest tools as having personalities. Perhaps this is because we have poured ourselves into them through constant use. You don’t have to be an animist to start to think of tools as having souls.[3]

So with the police: when our tools are tools designed to give us mastery over others, we find ourselves becoming habituated to wielding that mastery, and regarding everyone who challenges that mastery as a natural slave.

In the face of this presumed mastery, the resentment of the mastered is not at all surprising.

Evan Selinger wrote insightfully about the way tools of mastery like guns affect us in an article in The Atlantic a few years ago. I was especially struck by a line he cited from Bruno Latour:

"You are different with a gun in your hand; the gun is different with you holding it. You are another subject because you hold the gun; the gun is another object because it has entered into a relationship with you."We don't enter relationships without both parties being affected; both we and the gun are altered by this holding of the gun. Guns are very strong tools; therefore it takes enormous strength of character to wield one without being deeply and powerfully affected by it. The gun mediates the relationship between the one holding it and the one at whom it is pointed. This is not something anyone can easily control.

So if you give your police armor and military weapons, it should not surprise you if they begin to regard themselves as engaging in military activity. And it similarly should not surprise the police when the unarmed, un-armored populace feels that the police is not acting "to serve and protect" but quite the opposite.

I don't mean to exonerate anyone by these words, but to try to explain why right now there appears to be a growing hostility between the police and civilians. Police have a very hard job to do. Police officers I know have described long hours of dealing with people at their very worst, day after day. I'm impressed by how many police manage to keep calm and help to defuse potentially explosive situations, and do so repeatedly, every day on the job. And as more Americans own and carry handguns, it does not surprise me that many officers now wear bulletproof vests. They never know who might fire a foolish and angry shot, and they want to return to their families at the end of the day, alive and intact. That's not hard to understand.

But all of us face a hard choice. As I've argued before, we need good laws, and we need to maintain and enforce those laws. However, enforcement should not primarily mean the use of force, but a well-working judicial system, supported by good schools and watched over by excellent journalism. And we need one thing more: we need to become better people, to enact and inhabit the virtues we most wish to see in others. Intentional actions are like tools; as we dwell in them, they become the way we know the world, and, just as we hold on to them, they hold on to us.

This is what we should encourage in ourselves and in others. Not more and stronger weapons but better lives, lived nakedly and as unprotected from others as we dare. The armor we put on becomes the wall that divides us, and it becomes the lens through which we see some things, and because of which other things - like the humanity of our neighbors - becomes wholly invisible.

[1] Jonathan Edwards, The Works of Jonathan Edwards: Scientific and Philosophical Writings. Wallace E. Anderson, ed., (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1980) p.225

[2] Michael Polanyi, Personal Knowledge. 59.

[3] Walker Percy, The Moviegoer. (New York: Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, 1969) 232.

∞

More Books Worth Reading

One of the great pleasures of being a teacher is reading. To do my job well, I have to read. If I don't read a lot, I won't keep up with my field and I'll be a poorer teacher. Fortunately, I like reading.

Even so, one of the great surprises of being a teacher is that, at the end of a long day of work reading, I like to unwind with a good book. Go figure.

The last few months have brought me a surfeit of good books to unwind with. Here are some of the recent books I've enjoyed:

Even so, one of the great surprises of being a teacher is that, at the end of a long day of work reading, I like to unwind with a good book. Go figure.

The last few months have brought me a surfeit of good books to unwind with. Here are some of the recent books I've enjoyed:

- Richard Russo, Straight Man. This is one that has been recommended to me so many times by so many people I finally bought it and read it. If you work in a small college humanities department, trust me: you'll feel at home in this book.

- J. M. Coetzee, Elizabeth Costello. This is another that was recommended to me. It takes the form of a series of lectures delivered by a novelist, with very little framing around each lecture. The lectures stand alone, but all together they give the picture of an artist at work trying to figure out what exactly she is doing, what she believes, and why. Coetzee is really a philosophical novelist, and he does a remarkable job of engaging directly with figures like Descartes and Kant and Peter Singer.

- Dave Eggers, How We Are Hungry. Eggers' short stories are like David Foster Wallace's, but less frenetic and wild and so a little easier to read. I love the genre, and I'm always fascinated by people like Eggers and Wallace who explore its edges. I don't love this book, but it has kept my attention as a kind of intellectual exercise, and it is like a garden filled with tiny blossoms that delight the eye when you slow down and look closely.

- Matthew Dickerson, The Rood And The Torc. Dickerson is a friend of mine and my co-author, so there's my disclosure. Now let me say this about Dickerson: there are good reasons why he's my friend and my co-author, and this book illustrates some of them. He's a natural, easy storyteller who makes you glad you kept turning the pages. His prose is light, disappearing from the eye, easily replaced with a mental image of the place and the characters. This is one of several novels he has written about the peripheries of Beowulf, a beautiful story about poetry, songs, medieval Europe, and the cost of making the right choices. Reading this book was the first time I felt like I could see medieval life, not just read about it. Homes and hearths come alive with smoke and roasting meat and moving songs; the Frisian landscape and the rolling sea and the smell of cowherds seem to lift off the pages and into my imagination as I read it. John Wilson is right: this is "a splendid historical novel." Dickerson is brilliant, and so is his prose.

-

Hunter S. Thompson, Screwjack. This is the book Carlos Castaneda would have written if he'd admitted he was writing fiction. You feel the intoxication, and you believe it.

- Herman Melville, Moby Dick. This is one of those books that everyone knows and nearly nobody reads. It is long, and full of words. Lots and lots of words. But wow. It is one of those rare books that gives me the sense that every sentence was the child of long and serious reflection. Reading this was like taking a really good class. Naturally, I bought myself a "What Would Queequeg Do?" t-shirt to mark this milestone in my life. You can get yours here.

- Nathaniel Hawthorne, Mosses From An Old Manse. And this is like Melville. You read it because at the end, you discover that what seemed to be a simple story about a simple thing makes you understand your world a lot better.

- John Steinbeck, The Moon Is Down. I love Steinbeck, so I bought this book not knowing a thing about it. Turns out Steinbeck wrote it as a propaganda piece. He wanted to give a picture of what it would look like to live in, say, Norway or Denmark under Nazi rule, and how that occupation could lead to resistance. What I love about Steinbeck is, more than anything, his desire to portray people with sympathy. The Nazis in his book are real people, believable, and even likeable. I wish we had more people able to portray our contemporary enemies with such sympathy. If we could do so, we could love them better, and I think we could better understand how to resist them. As a bonus, towards the end of the novel there is a prolonged reflection on the meaning of Plato's Apology of Socrates.

- Patrick Hicks, The Commandant of Lubizec. (Another disclosure: Hicks is also my friend.) I was pretty sure I'd read all I needed to read about the Holocaust. I grew up with survivors. I've read all the usual books, I teach several in my classes. I didn't want to hear any more. But Hicks has done something truly remarkable in this fictionalized account of Operation Reinhard. In fact, what he's done is similar to what Steinbeck does: he has written about people with real sympathy and insight. It's a hard read because he spares us nothing, but that's precisely what makes it such a good read. Here's a short video about the book:

∞

Downstream: My New Book On Brook Trout and Appalachian Ecology

You can find it here, on the publisher's website, for a very reasonable price.

It is now listed on Amazon as well, though not yet in stock there.

I'm very grateful for the foreword by Nick Lyons, the afterword by Bill McKibben, and the kind words offered by such a wide range of brilliant scholars of theology, literature, and science, like Eugene Peterson, Andrea Knutson, Kurt Fausch, and John Elder.

It is now listed on Amazon as well, though not yet in stock there.

I'm very grateful for the foreword by Nick Lyons, the afterword by Bill McKibben, and the kind words offered by such a wide range of brilliant scholars of theology, literature, and science, like Eugene Peterson, Andrea Knutson, Kurt Fausch, and John Elder.

∞

This week I was privileged to watch a small drama acted out in my bee balm. The flowers grow close together, creating a diverse and compact set of micro-environments. A quick glance won't reveal much, but if you sit still and let your eyes shift their focus thousands of small lives start to appear.

The plot is only about a square meter, but these plants provide habitat and hunting grounds for numerous orb-weavers, jumping spiders, and funnel-web spiders. It's a treat to find an argiope or a goldenrod spider in these places. They may be deadly to insects, but they're a beautiful part of the ecosystem.

In the first photo you can see, in the lower left, a long-jawed orb weaver. If you look to the upper right, you'll see another.

Here's what happened: a small biting fly landed on my leg while I was watching the spiders, and it bit me. I flicked it off, and it landed on this web. For a moment, the spiders did nothing while the fly tried to disentangle itself. I couldn't help thinking of karma.

After a second or two, the spider in the lower left dashed out to seize the fly. This much could have been expected, I think. What came next surprised me, though. The second spider dashed out and seized...the first spider, as you can see in the second and third photos.

In the third photo you can see that the spiders are entirely engrossed with each other, while the fly is being ignored by them. The two spiders remained tangled like this for a while, without moving. Eventually, I was being bitten by too many flies and so I left.

Half an hour later I came back with my camera to see how it had gone. I was sure the spider that built the web would be dead, since it appeared to have been at a disadvantage in the fight.

Arachno-Drama In My Backyard (WARNING: Contains spider images)

|

| Two long-jawed orb-weavers in my garden. |

The plot is only about a square meter, but these plants provide habitat and hunting grounds for numerous orb-weavers, jumping spiders, and funnel-web spiders. It's a treat to find an argiope or a goldenrod spider in these places. They may be deadly to insects, but they're a beautiful part of the ecosystem.

In the first photo you can see, in the lower left, a long-jawed orb weaver. If you look to the upper right, you'll see another.

Here's what happened: a small biting fly landed on my leg while I was watching the spiders, and it bit me. I flicked it off, and it landed on this web. For a moment, the spiders did nothing while the fly tried to disentangle itself. I couldn't help thinking of karma.

|

| One spider rushed in to seize the other when it went for the fly. |

In the third photo you can see that the spiders are entirely engrossed with each other, while the fly is being ignored by them. The two spiders remained tangled like this for a while, without moving. Eventually, I was being bitten by too many flies and so I left.

Half an hour later I came back with my camera to see how it had gone. I was sure the spider that built the web would be dead, since it appeared to have been at a disadvantage in the fight.

|

| Here they are ignoring the fly and grappling with each other. |

Surprisingly, I found the fly gone, and both spiders had returned to their previous positions, as you can see in the fourth photo. I suppose this could have been a territory fight, or mating, or competition for prey. I don't know.

The best part of this is discovering something new that was going on in my own garden about which I know next to nothing. Since then I've been poring over books and doing web searches when I have spare time. If you know more about this species and what was going on here, I'd love to hear from you.

The best part of this is discovering something new that was going on in my own garden about which I know next to nothing. Since then I've been poring over books and doing web searches when I have spare time. If you know more about this species and what was going on here, I'd love to hear from you.

|

| And then they returned to their earlier positions. |

∞

Protecting Borders, Loving Neighbors, And The Economics Of Child Migration

Time Magazine reported last week that President Obama is seeking 2 billion dollars to reduce the flow of young illegal immigrants across the U.S.-Mexico border.

Too often our approach to this problem is, like many U.S. political questions, polarized into mutually repellent views about how we should view our laws. Should we reform them or enforce them? Let me suggest another angle from which to consider the problem.

Eight years ago, Reynold Nesiba (an economist who is my friend and colleague) and I co-taught a course for American students in Nicaragua. The purpose of the course was to spend time thinking and talking about the effects of globalization on a small developing nation.

We both prefer to teach contextually, so that the assertions of our readings and lectures can be supported and challenged by what the students see and experience in the places we visit.

We spent time with collective coffee growers, and with big coffee processors; with small, independent textile workers and in an international textile plant built in a tax-free zone in Managua. We did homestays and met with development workers, a health clinic and a local church. We met with and listened to as many people, from as many points of view, as we could.

The downside to teaching this way is that both students and professors become much more aware of the complexity of the problems of globalization, and facile, armchair solutions to those problems tend to fall quickly to pieces. That is to say, the downside to teaching this way is that it makes it harder to maintain simplistic and dogmatic views. Which is to say, it's a good way to educate people.

Although the course made many things unclear, it made a few things clearer. Among them are these:

If I'm right, though, then it gives some context to the persistent problem of illegal migration across our southern border, and it suggests a remedy.

The problem is plain: poor people are following the money trail, and fleeing the harsh economic conditions that prevail in poor countries.

The remedy is also plain, even if it is not easy: we need to figure out a way to increase the flow of capital into places like Nicaragua, and to do it in such a way that it increases jobs (not merely increasing the income of the top earners) and increases the tax base. One such possibility - especially if my second bullet point, above, is correct - would be to examine the way farm subsidies might actually be decreasing our ability to secure our borders. Our nation reaps profit from Nicaragua. Is it possible to do so in a way that also benefits Nicaragua?

I don't mean to pretend to be an expert here. I do have some relevant experience in Central America (from teaching regularly in Nicaragua, Guatemala, and Belize) but it's far from being hard data. But surely what we need is not fewer anecdotes but more stories from and about people who are most affected by the economies of our several American nations. If we are to love our neighbors, we need to learn who they are and what drives them. A mother who would send her young child, alone, across Mexico in search of a new life is either wicked or desperate, and the latter seems the likelier story. the roots of the word "desperate" mean "without hope." Loving our neighbors surely must include trying to give hope to the hopeless, and not merely building a wall across the only path towards hope that they can imagine.

Too often our approach to this problem is, like many U.S. political questions, polarized into mutually repellent views about how we should view our laws. Should we reform them or enforce them? Let me suggest another angle from which to consider the problem.

Eight years ago, Reynold Nesiba (an economist who is my friend and colleague) and I co-taught a course for American students in Nicaragua. The purpose of the course was to spend time thinking and talking about the effects of globalization on a small developing nation.

We both prefer to teach contextually, so that the assertions of our readings and lectures can be supported and challenged by what the students see and experience in the places we visit.

|

| Coffee beans grown in Nicaragua. |

We spent time with collective coffee growers, and with big coffee processors; with small, independent textile workers and in an international textile plant built in a tax-free zone in Managua. We did homestays and met with development workers, a health clinic and a local church. We met with and listened to as many people, from as many points of view, as we could.

|

| Workers sort coffee beans. |

Although the course made many things unclear, it made a few things clearer. Among them are these:

- The economy of Nicaragua is closely tied to the economy of the United States;

- Many Nicaraguans have had to leave their family farms because cheap exports from the United States make it impossible to sell their produce and grain at competitive prices;

- Those who leave the family farm often fail to find work in the cities;

- One cause of this is that the work conditions in the cities are largely established and controlled by the international firms that can easily relocate to other poor countries if their requirements are not met. This keeps wages low, and makes it difficult for the country to receive any tax benefit from international industry;

- So capital freely flows out of the country and across borders;

- People follow the capital as it flows.

If I'm right, though, then it gives some context to the persistent problem of illegal migration across our southern border, and it suggests a remedy.

The problem is plain: poor people are following the money trail, and fleeing the harsh economic conditions that prevail in poor countries.

The remedy is also plain, even if it is not easy: we need to figure out a way to increase the flow of capital into places like Nicaragua, and to do it in such a way that it increases jobs (not merely increasing the income of the top earners) and increases the tax base. One such possibility - especially if my second bullet point, above, is correct - would be to examine the way farm subsidies might actually be decreasing our ability to secure our borders. Our nation reaps profit from Nicaragua. Is it possible to do so in a way that also benefits Nicaragua?

I don't mean to pretend to be an expert here. I do have some relevant experience in Central America (from teaching regularly in Nicaragua, Guatemala, and Belize) but it's far from being hard data. But surely what we need is not fewer anecdotes but more stories from and about people who are most affected by the economies of our several American nations. If we are to love our neighbors, we need to learn who they are and what drives them. A mother who would send her young child, alone, across Mexico in search of a new life is either wicked or desperate, and the latter seems the likelier story. the roots of the word "desperate" mean "without hope." Loving our neighbors surely must include trying to give hope to the hopeless, and not merely building a wall across the only path towards hope that they can imagine.

*****

| |

| The old cathedral of Managua. Unused since it was damaged by an earthquake 40 years ago. |

Here are a couple more photos from our course. I've only included photos from cooperatives because the international firms we visited prohibited photography, claiming they were protecting "trade secrets." As near as I could tell, there wasn't much to protect in those places, since the machinery was all very simple: sewing machines, bean sorting machines and baggers. More likely, they were concerned about bad publicity arising from documentation of their working conditions. The photo of the cathedral in Managua is a reminder of how poor the capital city is: such a beautiful building has languished for four decades because there are no funds to restore it.

|

| A coffee cooperative in the mountains of Nicaragua. |

|

|||

| A sewing cooperative. |