Shelfie.

These are books that I’ve brought to class this week or have pulled off the office shelves for discussions with students. Quite a few others have already been reshelved.

Myths as Containers of Insight

“Like a woven basket or a clay pot, a story is a container. It provides a shape for holding some character, some act or insight, some lesson we can’t afford to lose.” (Scott Russell Sanders)

Sanders says we are a storytelling species, that we make sense of the world through myths and stories.

Aristotle, two thousand years before Sanders, says “A man who is puzzled and wonders thinks himself ignorant (whence even the lover of myth is in a sense a lover of Wisdom, for the myth is composed of wonders.)”

(The words from Scott Russell Sanders are from the chapter entitled “The Warehouse and the Wilderness” in A Conservationist Manifesto. p 74. Indiana University Press, 2009. The words from Aristotle are taken from his Metaphysics, 982b, and the translation is from The Basic Works of Aristotle, Richard McKeon, ed. New York: Random House, 1941). That phrase “love of wisdom” is another way of saying “philosopher.”

The longer I’ve taught philosophy the more strongly I believe that it is a mistake to teach it outside of historical and cultural context.

Litany of Joys

Some of today’s delights:

- Chance meeting with a friend I haven’t seen in years, and who is flourishing in a new job.

- A quick visit with an alum who is doing great things with her life.

- Tea with an old friend who has also been an informal mentor.

- Dinner with two friends whose company and conversation fill my soul. (The food was also awesome!)

- Exchange of texts with a few other friends, with the plan to see one of them tomorrow.

Had so much fun I didn’t take photos or sketch, just enjoyed good company and good conversation.

Friendship is like manna.

One of the highlights of my week: singing a lullaby to my grandson in harmony with my son.

Prairie chicken sketch in my notebook.

Sitting at a conference session today I decided to sketch something from memory. Feeling pretty good about how this bird turned out.

The AI alt text reads “A whimsical sketch of a bird with bold lines and subtle color hints appears on lined paper.”

I’ll take it.

Today’s breakfast sketch: Hell’s Kitchen

I have two notebooks open in front of me as I eat slowly. One is a sketchbook, one is lined paper.

Together these books are a place for reviewing yesterday’s conference sessions and conversations. And they’re a good preparation for what I might learn today.

Yesterday I had the joy of hearing one of my alums give a talk about the sustainability business she started at my university. She spoke frankly about her joy in doing good, and her frustrations at the lack of support she had when trying to save money for her alma mater and to do good for the community. This kind of work is not just about making money or solving some discrete problem. It’s also about changing hearts, minds, habits, culture. It’s long work, with a long (and hopefully fat) tail. And I think it is worth it. She and I both want to be good neighbors now, and good ancestors to those who won’t be born for another seven generations.

As I eat slowly in this quiet place, as the city around me wakes up, I am mindful of the people who live here now, and hopeful that we can make a positive difference not just for our neighbors but for all who will someday live here.

20 Minute Pallet Bench

My philosophy student and I made a garden bench by salvaging a long pallet from the trash on campus.

We got a bench out of it, but he also learned how to use tools he hadn’t used before, and he got a lesson in tinkering, and in upcycling.

We throw away a lot of pallets, and lots of other things that could find second uses.

And too often in our quest for efficiency in education we discard opportunities.

I’m glad to have participated in this twenty minutes of salvaging both the wood and the learning.

Sketch: Hope Breakfast Bar

Quick sketch while waiting for some friends to arrive for breakfast in Minneapolis. The cards on the table suggest that the place is driven by something more than making money by selling food. They’re making a place. They also have a one hour limit on their tables (understandable) so it’s a place with limits.

My grandson is sleeping so I am trying to figure out how to sketch bison. Hopefully by the time he’s my age we will also have figured out how to let the bison roam their native plains again, too. One step at a time.

Sketching insects I’ve seen this week.

Two Central American Butterflies

I’ve been watching the butterflies here at home slowly vanish from the landscape as the days grow shorter. Unusually warm weather keeps them coming back, but yesterday I only saw one colias.

On a whim this morning I decided to sketch one of the butterflies I saw seven years ago in the medicinal plants garden run by my Itzá friends and partners in Petén, Guatemala.

The colors reminded me of another butterfly I saw last year in Costa Rica while working with some sea turtle scientists and some of the scientists from South Dakota State University and some scientists at the Sioux Falls Zoo and Aquarium, where I serve on the Board of Directors.

So this morning’s reverie included the butterflies I am no longer seeing here in Sioux Falls, and some that continue to reside in my memory from my many research and teaching trips to Central America.

If these appeal to you, let me encourage you to consider taking a trip to Petén. La Asociación Bio-Itzá does great conservation work on a shoestring budget that is largely funded by ecotourism. Others in the area like Francisco Asturias at Parque Mirador Azúl also do great work that depends on tourism. Check them out. They’re off the beaten path, but they’re good people doing good work, and they can show you why the forest is worth conserving.

Pocket notebook

When I was a boy Dad worked for IBM, and he carried one of these notebooks in his pocket most of the time. Some of my good friends from those days (who also had IBM dads) still carry paper notebooks, and so do I. We grew up with great tech, but some of the best tech is also the simplest, and it’s hard to beat paper and pen. I can write, sketch, make diagrams and design solutions while building things. Such wonderful technology!

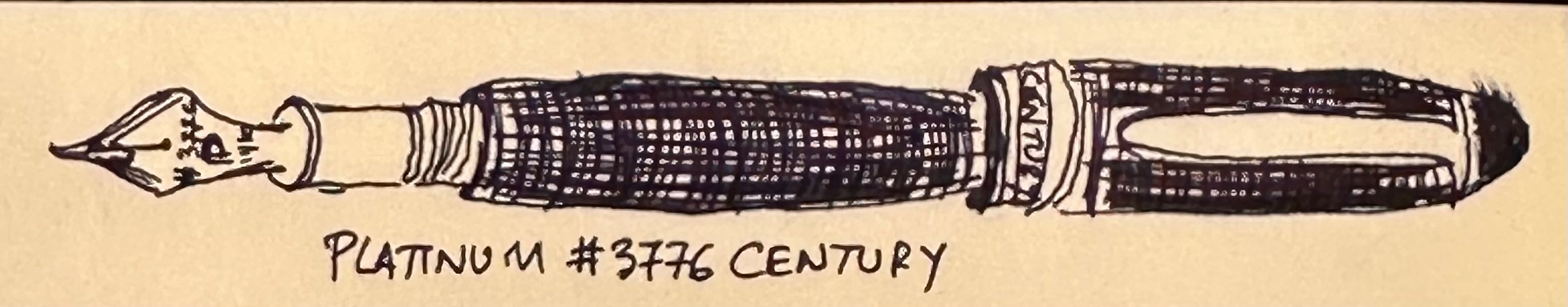

Really loving this pen my daughter gave me when she finished law school.

Loving it so much that I used it to sketch its own likeness. Such a smooth writing tool!

“The best maxim in writing, perhaps, is really to love your reader for his own sake.”

Charles S. Peirce, “Private Thoughts: Chiefly On The Conduct Of Life,” lxxv, March 17, 1888.

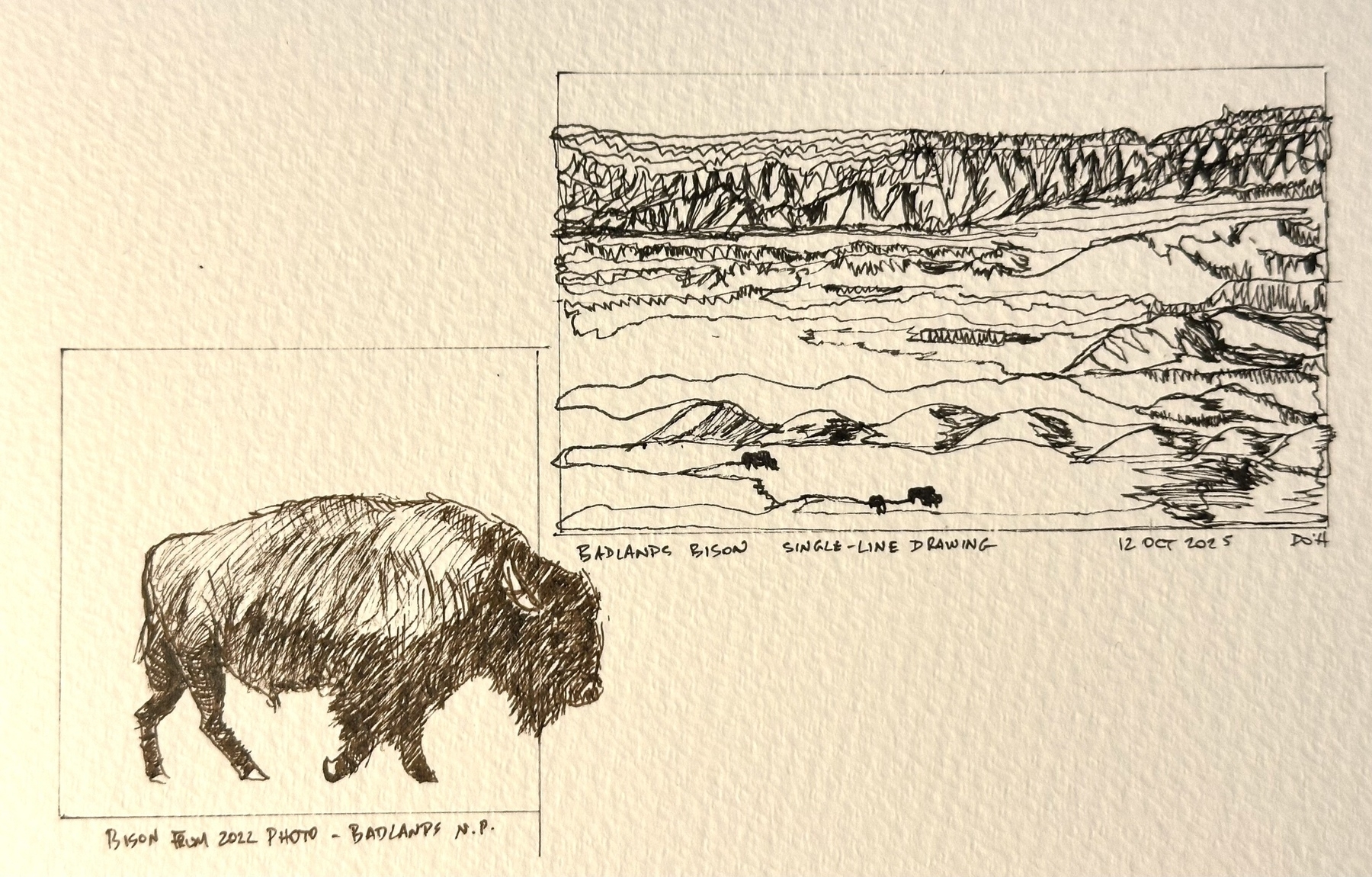

Badlands fauna for Felix

One more page in the books for my grandchildren. I’m trying to document the beautiful things I see, in hopes that the grandkids will someday enjoy both the books and more wonders in this world.

This one is in my grandson’s book. Two images from my trip to the Badlands National Park this weekend.

Both the grandkids are infants, born weeks apart this year. Hopefully they will share these books with one another someday.

Meadowlark for Claire. Part of the book I am writing for my infant granddaughter, documenting the beautiful things I am seeing in the world.

More Badlands Bison

Decided to add one more bison to the sketch page. This one is from a photo I took in the Badlands in 2022. The bison was grazing right near where my sleeping bag and I were stretched out on the ground for stargazing. It added wonderfully to the number of majesties I beheld on that trip.

This is part of my practice of nature journaling (I have required my environmental philosophy students to do this, and so I am doing it, too) and part of my practice of documenting the beauty I see in the world for my infant grandchildren, in hopes that they will appreciate what they see in my sketchbooks, and come to love and preserve for others what they see in this wonderful world that we share.

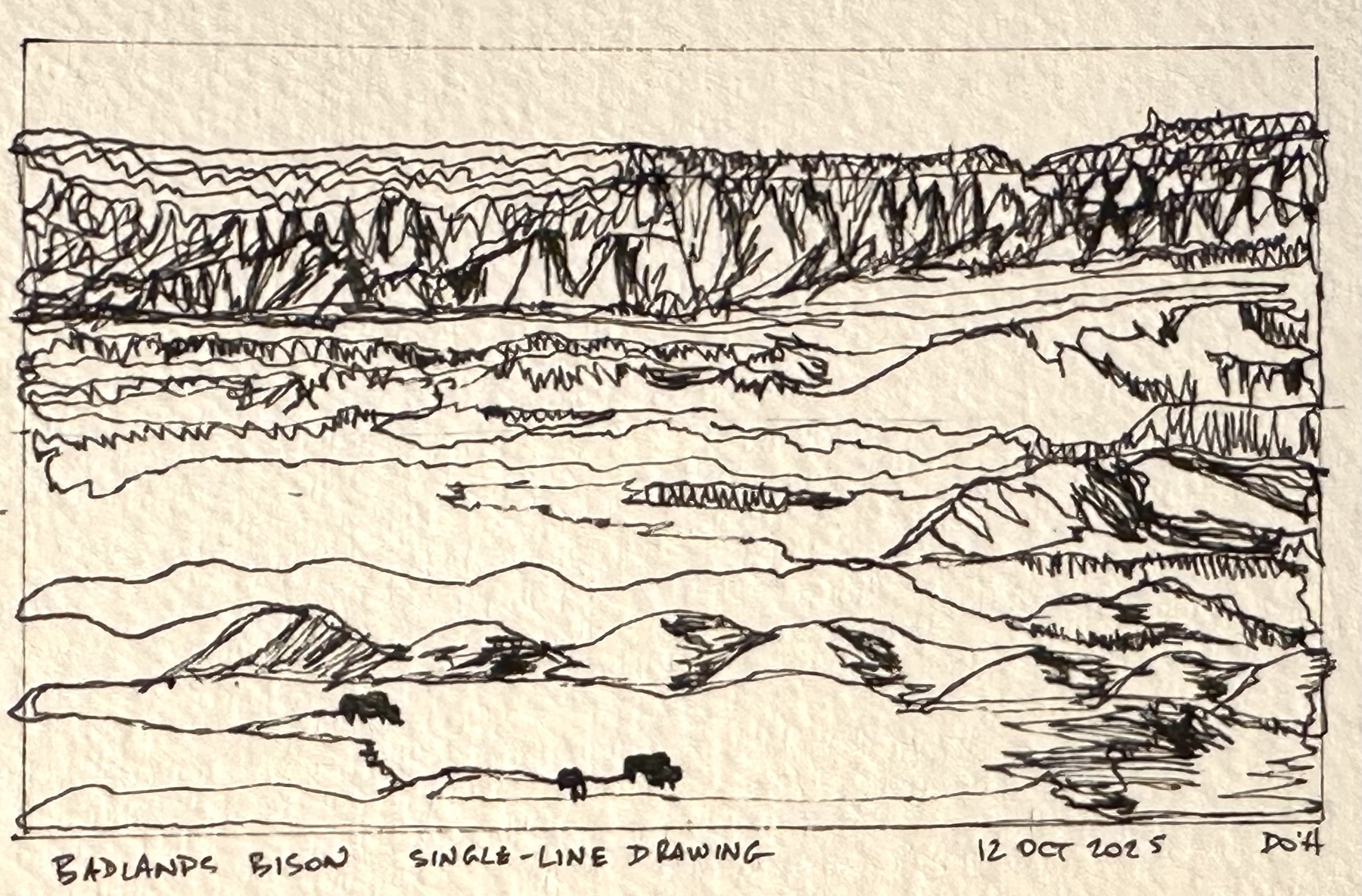

Single-line sketch: Badlands Bison

Bison grazing in Badlands National Park. This is an experiment with single-line drawing. The whole sketch was made without lifting the pen from the page. I sketched from a photo after doing some plein-air sketches yesterday in a wind that was strong enough that it was hard to keep my sketchpad from blowing away.

The bison in South Dakota number in the thousands, though they used to number in the millions. The herds that roam Badlands National Park and Custer State Park are the descendants of a small number of bison that were saved by a small number of people.

I often wonder what the ecology of our region would be like if the bison still existed in numbers like they once had.

To call them “badlands” is an injustice to just how good they are.

Bison grazing on tableland in the Badlands National Park in South Dakota yesterday.