Unvisited Tombs

In my last year of college I signed up for a course on the early English novel. In the first week the professor assigned George Eliot’s Middlemarch.

I had enjoyed reading long novels on my own, but when assigned an eight hundred page novel and given three days to read it, I quickly decided I had better things to do with my life.

I was already in a class on Cervantes (reading his original Spanish) and another class on medieval Spanish literature (often hundreds of pages of reading a day in that one) so I backed out and contented myself with a history class instead.

Some books are made for fast reading. Texts on biology and ecology I breeze through with exhilaration. When I read new research on malacology, I want to absorb it all quickly and then get out into the field as soon as possible.

Others are books I like to work through, like texts on mathematics. Some proofs are delights that need to be savored. Problem sets are, generally speaking, a gift, and a way of learning by playing.

Poems (especially short ones) and good novels are like landscapes. I don’t want to snap a quick photo and move on; I’d rather spend time wandering, seeing what grows there, feeling the ground under my feet.

So this year, a few (!) years after my senior year of college, I have returned to Middlemarch. And I’m so glad I am doing so when I have time to read it slowly. One chapter on Dr. Lydgate is full of criticism of higher education and of the pharmaceutical industry that still feels relevant today. Throughout, reflections on sainthood and on the individual lives of insignificant people in a small town (who’s to say these are not the same thing in any particular case?) are constant reminders of the hidden inner lives of the people next door.

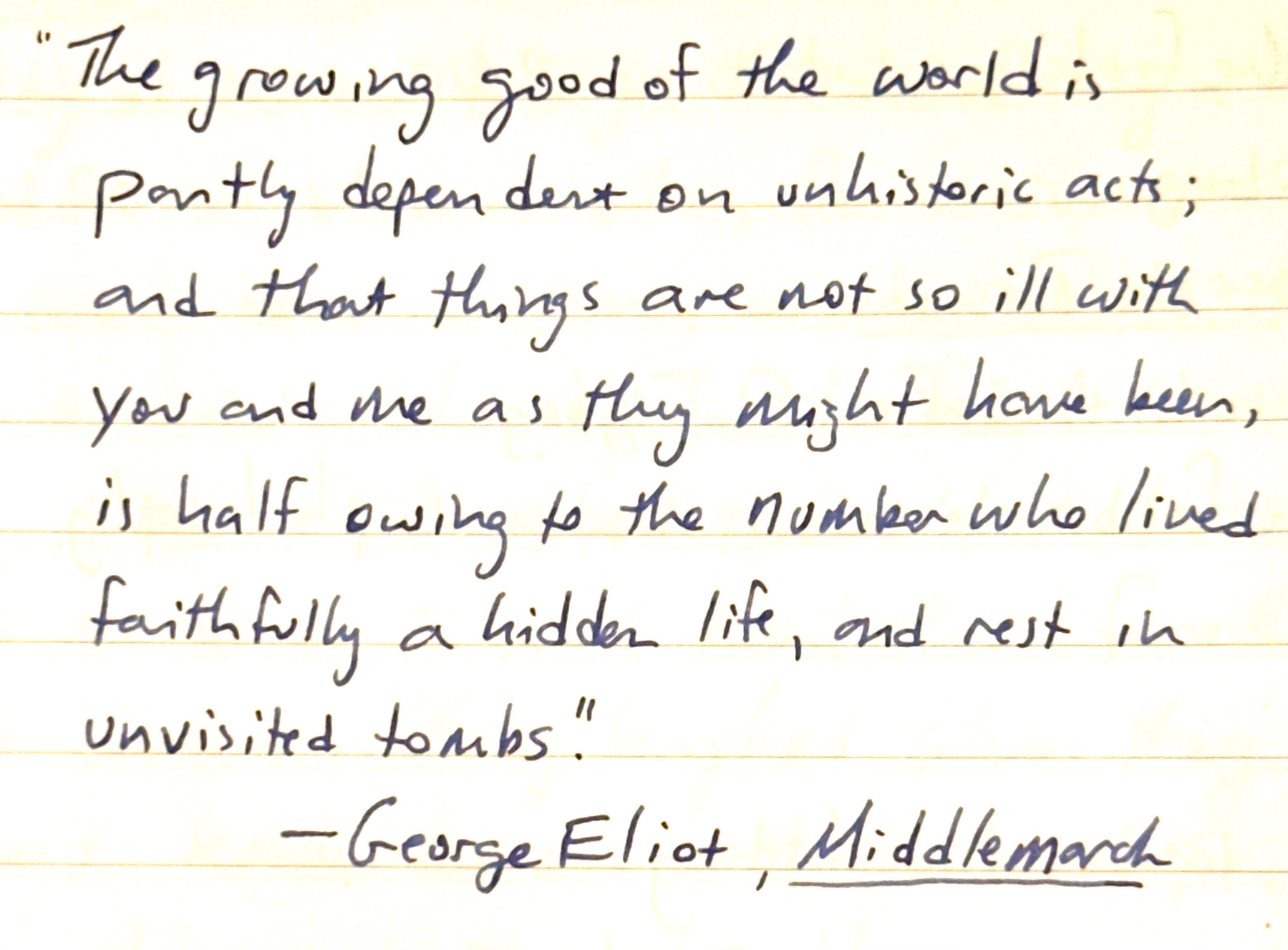

And of course there is that passage I have often returned to, the reminder that the goodness of my life and of yours are both dependent on the many people who made small decisions that now affect us.

Some of them “lived faithfully a hidden life,” and we will never know their names, but our lives are now better because of them.

It’s tempting to play the lottery, to start the Next Big Thing, to earn a Name for oneself, to make a splash and be remembered for it.

Most of us, however, won’t have our names on great buildings. Most of us won’t make the history books. Most of us won’t win medals of honor, or have our deeds engraved on great stones for all the ages to see.

But that should not prevent us from living faithfully, even if our lives are hidden. Even if (perhaps especially if) we never become known as “influencers” or bestselling authors.

Our only reward might be long rest in a tomb that is untroubled by visitors.

When I am dead, I might not care. But the thought of living now in such a way that others might someday benefit from it makes the small things feel like acts of love, like planting the seeds of trees that will outlast me, and give fruit and shade to others who need them someday.