agriculture

Of Kings and Wars and Gardens

Long ago there was a season for war. An ancient text about one of the kings of Israel tells us this:

"It happened in the spring of the year, at the time when kings go out to battle, that David sent Joab and his servants with him, and all Israel; and they destroyed the people of Ammon and besieged Rabbah. But David remained at Jerusalem."

Two points stand out to me:

1) When ancient kings went to war, they did so in the spring; and

2) King David didn't go this time.

The first point probably has to do with agriculture. An agrarian society like David's probably did not have much of a standing army. Men were free to fight in between the time for sowing seeds and harvest. Wars could be launched when the seeds were in the ground, and should end before harvest if the nation is not to starve.

The second point is the reason for the story. And it is a reminder that sometimes kings have big enough armies that they can send men to fight for them. In this case, because David stayed behind, he wound up taking the wife of one of his soldiers. When she got pregnant, David had the man killed.

It's foolish to think we can somehow go back to how things were even before David's time, when kings themselves would have to work for food.

But we can at least dream of kings who work their own gardens with enough care that they respect rather than covet the gardens and spouses of others.

Perennial Thinking in Education, Ag, and Culture - Lori Walsh interviews Bill Vitek and me on SDPB

One of the persistent themes of his work is the connection between culture and agriculture: the two shape one another.

|

| A bit of prairie, with perennial grasses. |

Another theme that is related to the first: we all eat, and we all think, and eating and thinking indluence one another.

A third theme: we tend to focus our thinking on the annual or the short-term, neglecting the perennial and long-term. having spent a few days with Bill, I'm now reflecting on what I find one of the most provocative parts of his work: what would it mean to shift from thinking of education as an annual crop to thinking of it as a perennial? Currently we begin planting at the beginning of the season, and we expect to harvest grades and graduates at the end of the term.

What if we thought of education in the way we think about caring for perennials? What if we considered school to be more like the planting of trees than like the planting of corn? Or what if we figured out a way (as they are doing at the Land Institute, where Bill is a collaborator with Wes Jackson - here's a link to one of their co-edited books) to give our annual crops perennial roots?

|

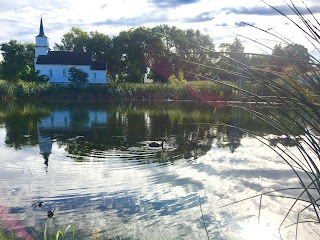

| A view of the Augustana University campus, with historic buildings. |

I have a lot of work and thinking and cultivating ahead of me, so I won't answer those questions here. If you have taken my classes, you already know how I have been working on this over the years (think of how I speak about grades and exams in my classes, for instance). And if you've read my books (like my book on C.S. Lewis' environmental thought, or my book on brook trout as indicators of both natural ecology and cultural ecology), you know I'm working on these ideas, and they will require long cultivation. I'm okay with that.

For now, feel free to listen to Bill and me as we are interviewed by Lori Walsh on South Dakota Public Radio.

20,000: Two Stories Of Water Pollution In The Dakotas

The first was a story about an oil pipeline leak in which 20,000 barrels of crude oil contaminated over seven acres of farmland. The Argus reports that in major oil-producing states like North Dakota oil spills must be reported to the state, but state law does not mandate the release of this information to the public. In other words, the state is free to keep this news quiet. One has to assume that the state legislators who wrote that law thought it was in the public interest to keep news of toxic spills quiet. It's better for us not to know about such things, I guess.

Anyway, the Argus lets us know that some state officials think there's no cause for concern: "state regulators say no water sources were contaminated, no wildlife was hurt and no one was injured." Oh, good.

The second story is about the disposal of some 20,000 cattle that died in a surprisingly early and heavy snowstorm earlier this month. This is a devastating loss for ranchers across western South Dakota. It represents an enormous financial loss, and it also creates a very difficult cleanup problem. The best solution for disposal of all the carcasses so far has been to dig two large pits. The Argus reports that there are strict regulations concerning the depth and soil of the pits.

According to the Argus, the reason for the pits is to make sure the dead cattle don't contaminate streams.

Which makes me wonder why there is so little concern for the oil spill in North Dakota. Obviously there is an important difference between bacterial and viral infections entering streams, on the one hand, and oil entering streams on the other hand. But surely both represent serious health hazards?

We are left with a peculiar contrast: a few cattle on the ground - something that happens in nature all the time - are a serious threat to the water, while a million gallons of crude oil spread across seven acres of farmland (presumably some rain falls there and washes into streams?) is barely worth telling the public about.

*****

Update: Since a number of people have asked me just what happened to the cattle in South Dakota, I am posting this link that I found to be a helpful reply to some questions about the storm and the loss of the cattle.

Empire and Total War

Of course I don't know, but it makes me think of a passage in the prophet Samuel. King David sends his army to fight, "in the season when kings go off to war," but he does not join them. He stays behind and winds up having an affair with a married woman, then arranging for her husband to die on the front lines to cover up David's dalliance. (By the way, David is remembered as one of the good kings.)

The bold passage above tells us something about the history of warfare: small states cannot afford total war. They can only go to war when their crops are in the ground, and must return before the crops are to be harvested. Not so with empires. Large states can draw soldiers from many places and so can afford to field an army year-round.

|

| Sometimes you're just in the right place to capture the photo. The Blue Angels soar past Walmart. |

While King David's state was small enough that it was still bound by the growing season, he was enjoying a period when his state had grown large enough that he could send his troops out without joining them, without committing himself to sharing in their triumphs and losses. And this detachment of the leadership from the fighting forces led to deep tragedy, and even to a kind of human sacrifice, wherein the king was willing to sacrifice one of his men to cover up the king's own error.

So while I don't know why the suicide rate is increasing right now, I am not surprised to learn that our troops are suffering. We commit them to long tours of duty, not just for part of a growing season but for years on end with only short rests. It is lamentable that they are often so far from us it is hard to even imagine what they endure, much less to share in it with them.

See my earlier post on the cost of war here.

Writing, Law, and Memory in Ancient Gortyn

|

| Gortyn, Crete |

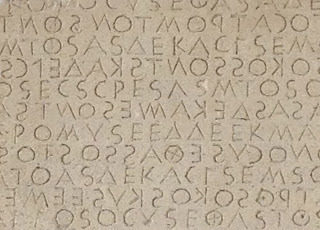

Even though I'm not an expert in the Doric dialect, I love to read this inscription, for several reasons that might interest even those who don't know Greek.

First of all, it has an unusual alphabet, containing fewer letters than modern or classical Attic Greek. It lacks the vowels eta and omega (for which it uses epsilon and omicron), and the consonants zeta, xi, phi, chi, and psi (for which it substitutes other letters or combinations of other letters: two deltas for zeta, kappa+sigma for xi; pi for phi; kappa for chi; pi+sigma for psi.)

It also uses a letter that has since fallen out of use, the digamma. The digamma (or wau) is probably related to the Hebrew letter waw (or vav) and to the Roman letter F, which it closely resembles. By the classical age it had dropped out of use in Greek, and is fairly rare, like the letters sampi and qoppa.

(There is also a digamma in Delphi, not far from the Athena Pronaia sanctuary, on an upright stone dedicated to Athenai Warganai. That second word is related to the Greek word for "work" or "deed," ergon, and also to our word "work." This stone, pictured below, evinces several peculiarities of archaic Greek script. Look at the second word, which looks like it says FARCANAI. The first letter is digamma; the third letter, rho, very much resembles the Latin "R"; the letter immediately after it, gamma, looks like a flattened upper-case "C.")

|

|

"Athenai Warganai" inscription at Delphi

|

Second, the writing is in boustrophedon style. Boustrophedon means something like "as the ox turns." Today we write in stoichedon style, in which all the letters face the same direction, like soldiers standing in formation. Boustrophedon is based on an agricultural, not a military ideal: the writer writes as a farmer plows. Write to the end of the line, and then, rather than returning to the left side of the page, turn the letters to face the opposite direction and write from right to left. When you read boustrophedon, your eye follows a zig-zag across the page -- or the stone.

Have a look at this close-up of the engraving at Gortys and look at the way letters like "E," "K," and "S" face in adjacent lines:

|

| Close-up of the Gortyn Code |

There are a lot of other reasons to like this place, and this inscription, but I'll limit myself to just one more thing for now: memory.

This inscription is one way that an ancient community deliberately remembered their laws. They wrote down what they decided, and that has affected our lives. Writing the law down makes it accessible to everyone, and makes judicial decisions transparent. It establishes a set of expectations for conduct in the community, and makes those expectations known even to aliens.

The code at Gortyn records (in Column IX, around the middle, if you're curious) the presence at court of someone in addition to the judge: the mnemon. You can see by the word's resemblance to our word "mnemonic" that it has to do with memory. The mnemon's job was to act as a witness to previous judicial decisions, and to remember them and remind the judge of those decisions. The mnemon's job was not to decide cases but to be a kind of embodiment of the law and therefore an embodiment of fairness.

Unfortunately, no mnemon lives forever. Presumably, the writing on the wall at Gortyn was a way of preserving what mattered most in the court, so that when they passed away, their memories would live on through the ages.

|

| National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Possibly a child's dish? The sixth letter is digamma. |

*****

Harold Fowler writes in a footnote to his 1921 translation of the Cratylus that under Eucleides the Athenians officially changed their alphabet from the archaic one to the Ionian alphabet in 404/403 BCE. This expanded their system of vowels, adding the long vowels eta and omega. It became known as the Euclidean Alphabet.

*****

If you can find it, Adonis Vasilakis' The Great Inscription of the Law Code of Gortyn (Heraklion/Iraklio: Mystis O.E.) is a great resource. It has a facsimile of the whole wall, a complete translation, and some helpful historical observations. ISBN 9608853400