brook trout

- Henry Bugbee, The Inward Morning. Don't try to read this book quickly, and if you're not prepared to do the hard work of thinking, move on and read something else. But if you're willing to read slowly and thoughtfully, this book can change your life. Bugbee was a philosophy professor and an angler.

- Henry David Thoreau, A Week On The Concord and Merrimack Rivers; The Maine Woods. Thoreau was an occasional angler, and an observer of anglers.

- Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac and the title essay in The River Of The Mother Of God, about unknown places. Leopold only writes a little about fish and fishing, but those occasional sentences about angling tend to be shot through with insight.

- John Muir, Nature Writings.

- John Steinbeck, Log From The Sea of Cortez. An apology for curiosity, in narrative form. One of my favorite books.

- Paul Errington, The Red Gods Call. Not brilliant writing, but a fascinating set of memoirs from a professor of biology who put himself through college as a trapper, and about how the Big Sioux River in South Dakota was his first real schoolroom. He talks a good deal about hunting and fishing and what he learned through encounters with animals.

- Kathleen Dean Moore, The Pine Island Paradox. Moore is an environmental philosopher who writes winsomely ans insightfully about what nature has meant to her family.

- Nick Lyons. Nick very kindly wrote the foreword to my book, and when I first got in touch with him about this I discovered he and I had lived only a few miles from each other in the Catskill Mountains for years. Sadly, by the time I discovered this I'd already moved away, and he was packing up to move to a new home, too. We both love the miles of small trout streams of those mountains, though. Nick has been a prolific writer and he has promoted a lot of great writing through his lifelong work as a publisher as well. Nick has a new book, Fishing Stories, just published in 2014.

- Norman Maclean, A River Runs Through It

- Ernest Hemingway, especially "Big Two-Hearted River" and the other Nick Adams stories

- James Prosek. Several books, including Trout: An Illustrated History; Early Love And Brook Trout; and Joe And Me: An Education In Fishing And Friendship

- Ted Leeson, The Habit Of Rivers

- Kurt Fausch’s new book, For The Love Of Rivers: A Scientist’s Journey. Brilliant writing by one of the world's leading trout biologists.

- Craig Nova, Brook Trout and the Writing Life. I also like his novels, and will recommend The Constant Heart.

- Christopher Camuto, who writes frequently for Trout Unlimited's journal, Trout.

- Ian Frazier, The Fish's Eye.

- Douglas Thompson, The Quest For The Golden Trout

- Izaak Walton, The Compleat Angler

- Dame Juliana Berners, The Boke Of St Albans, later editions of which contain A Treatyse of Fysshynge with an Angle, possibly authored by someone else.

- Nick Karas, Brook Trout (a nice collection of short works about brook trout, including some of my favorite stories)

- Lee Wulff

- Lefty Kreh

- John Gierach. Gierach has written a lot about angling, so it's not surprising that so many people mention him to me. Many of those mentions are positive, but some anglers mention his name with disgust. I haven't read much of his work, so I can't yet say why.

- David James Duncan, The River Why. This is a fun novel set in the Northwest, but it reminds me of the New Haven River in Vermont: there are some long dry stretches one has to plod through, but repeatedly one comes to depths that make the flatter, shallower parts worthwhile.

- Thomas McGuane, The Longest Silence.

- Bill McMillan

- Roderick Haig-Brown

- Mike Valla, The Founding Flies

- Michael Patrick O’Farrell, A Passion For Trout: The Flies And The Methods

- Peter Reilly, Lakes and Rivers of Ireland

- Derek Grzelewski, The Trout Diaries: A Year of Fly-fishing In New Zealand and The Trout Bohemia: Fly-Fishing Travels In New Zealand

- Eeva-Kaarina Aronen, Die Lachsfischerin. A novel set in Finland, about fly-fishing and fly-tying in the 18th century. The title translates as “The Salmon Fisherwoman”

- Ian Colin James, Fumbling With A Fly Rod (Scotland)

- Zane Grey, Tales of the Angler’s Eldorado: New Zealand

- Leslie Leyland Fields, Surviving the Island of Grace; and Hooked! Fields and her family are commercial fishers in Alaska, and her writing comes recommended to me from a number of sources.

- Sheridan Anderson, The Curtis Creek Manifesto

- Harry Middleton, The Earth Is Enough: Growing Up In A World Of Fly-fishing, Trout, And Old Men (Memoir)

- Paul Schullery, Royal Coachman: The Lore And Legends of Fly-fishing

- Gordon MacQuarrie

- Patrick McManus

- Vince Marinaro, The Game of Nods

- Rich Tosches, Zipping My Fly

- Robert Lee, Guiding Elliott

- Peter Heller, The Dog Stars (novel)

- Paul Quinnett, Pavlov’s Trout

- Dana S. Lamb Where The Pools Are Bright And Deep; Bright Salmon and Brown Trout

- John Shewey, Mastering The Spring Creeks

- Ernest Schweibert, Death of a Riverkeeper; A River For Christmas

- Richard Louv, Fly-fishing for Sharks: An Angler’s Journey Across America

- John Voelker’s short story “Murder”

- Dave Ames, A Good Life Wasted, Or 20 Years As A Fishing Guide

- Craig Childs, The Animal Dialogues, especially the chapter “Rainbow Trout”

- Randy Nelson, Poachers, Polluters, and Politics: A Fishery Officer’s Career

- Anders Halverson, An Entirely Synthetic Fish: How Rainbow Trout Beguiled America And Overran The World

- Thomas McGuane, A Life In Fishing

- Bob White

- Robert Ruark

- Tom Meade

- Hank Patterson

- Virginia Woolf, Mrs. Dalloway. (Mixed feelings about this one. My mind enjoyed it more than my aesthetic sense did, if that makes sense.)

- John Steinbeck, Cannery Row and Of Mice and Men. (I discovered Steinbeck late in life, thanks to a friend's recommendation. I've also recently read his Log From The Sea of Cortez and Travels With Charley In Search Of America. I think these two will forever shape me as a writer.)

- Graham Greene, Our Man In Havana, The Quiet American, The Honorary Consul, Travels With My Aunt, The Power And The Glory. (I will let the number of titles speak for itself.)

- Alan Paton, Cry, The Beloved Country. (I was surprised by how contemporary this old book felt, and by how relevant to America an African book could feel.)

- The Táin. Because I have a thing for reading really old books, and this is one of the oldest from Europe.

- China Miéville, Kraken. (London. Magical realism. Bizarre and witty.)

- J. Mark Bertrand, Back On Murder (I don't read many detective novels, but I really enjoy Bertrand's prose.)

- Cormac McCarthy, The Road. (The final lines spoke to my salvelinus fontinalis -loving heart.)

- David James Duncan, The River Why (I've re-read this one a few times. If you like trout and philosophy, you might like this book.)

- Mary Karr, Lit. (Third in a series of memoirs. Some of the best storytelling I've read in a long time. Brilliant insights into addiction, love, and prayer.)

Catch Your Breath: A Winter Meditation on Trout - My latest article, in Hothouse

My latest publication, a winter meditation on the beauty of brook trout, in Hothouse // Solutions. This is my first publication in collaboration with my son, Michael O'Hara, my favorite pro photographer.

A little taste of my article:

The trout is, for me, an icon of what I hasten to ignore.

I hope you enjoy this short read. Consider subscribing to Hothouse.

We can all use good news, after all. I like the short format and the focus on solutions, not just on problems.

Of course, if you like what I've written here, you might also like my book on brook trout.

Perennial Thinking in Education, Ag, and Culture - Lori Walsh interviews Bill Vitek and me on SDPB

One of the persistent themes of his work is the connection between culture and agriculture: the two shape one another.

|

| A bit of prairie, with perennial grasses. |

Another theme that is related to the first: we all eat, and we all think, and eating and thinking indluence one another.

A third theme: we tend to focus our thinking on the annual or the short-term, neglecting the perennial and long-term. having spent a few days with Bill, I'm now reflecting on what I find one of the most provocative parts of his work: what would it mean to shift from thinking of education as an annual crop to thinking of it as a perennial? Currently we begin planting at the beginning of the season, and we expect to harvest grades and graduates at the end of the term.

What if we thought of education in the way we think about caring for perennials? What if we considered school to be more like the planting of trees than like the planting of corn? Or what if we figured out a way (as they are doing at the Land Institute, where Bill is a collaborator with Wes Jackson - here's a link to one of their co-edited books) to give our annual crops perennial roots?

|

| A view of the Augustana University campus, with historic buildings. |

I have a lot of work and thinking and cultivating ahead of me, so I won't answer those questions here. If you have taken my classes, you already know how I have been working on this over the years (think of how I speak about grades and exams in my classes, for instance). And if you've read my books (like my book on C.S. Lewis' environmental thought, or my book on brook trout as indicators of both natural ecology and cultural ecology), you know I'm working on these ideas, and they will require long cultivation. I'm okay with that.

For now, feel free to listen to Bill and me as we are interviewed by Lori Walsh on South Dakota Public Radio.

Professors of Trout

Really, this shouldn't be too surprising. Fly-fishing requires us to look attentively, seeing past the surface of the water in order to discern what is happening deeper down. Far more than simply catching fish, fly-fishing is a practice of reading water as though it were a natural text.

Several authors, professors, and fellow-thinkers have been helping me to deepen my literacy in these streams of thought lately. Among them are Kurt Fausch, Douglas Thompson, and David Suchoff.

Fausch is one of the world's authorities on trout biology and ecology. I had the privilege of reading a draft of Fausch's forthcoming book, For The Love Of Rivers, (see the book trailer here) and I highly recommend it. It is a lovely marriage of science and lyrical writing. You'll learn a lot about the life of rivers, written by a remarkable writer who loves them deeply.

Thompson's book, The Quest For The Golden Trout is next on my to-read list, but I've already snuck some glimpses at it and I am eager to get to it. I'll post more about it when I'm done. Meanwhile, check out his webpage.

I discovered Suchoff recently when I saw one of his students fly-fishing for bonefish in Belize. I teach a January-term field ecology course for Augustana College in Guatemala and Belize. One morning I looked out over the intertidal flat and saw a young woman casting a heavy fly in turtle grass on South Water Caye. I ran into her later on shore and she told me about a terrific class Suchoff teaches at Colby College in Maine. He teaches them the literature of fly-fishing, arranges professional instruction, then takes his students fishing in California, and teaches them to write about it. You can find him on Twitter, too.

One of the joys of research is that it gives me the excuse to write to strangers who share my interests and ask them to teach me what they know. My acquaintance with two of these professors is quite new, but already I've learned from them. The third, Fausch, I've known for long enough that he reviewed a draft of my book and kindly pointed out a few errors before I made them permanent in print.

These are, as I've said, just a few of the university professors who study trout. Are you another? I'd love to hear from you if so.

Recommended Reading: Fly-Fishing and Trout

|

The focus of the course will be the char species of Alaska. These species, all members of the genus salvelinus, are commonly thought of as trout. Brook trout and lake trout are both char, as are Dolly Vardens and arctic char.

These are beautiful fish. I think many anglers love them simply because they are so beautiful to look at. When I pull one from the water I am immediately torn between wanting to hold this precious thing closely and the urge to release it immediately, before my coarse hands pollute its loveliness. The name "char" might come from Celtic roots, like the Gaelic cear, meaning "blood." They are more multi-hued than rainbow trout. The red on their sides and fins catches the eye and holds the gaze.

Over the years I spent researching and writing my own book on brook trout, I did a lot of reading. Some books call me back again and again, like Henry Bugbee's The Inward Morning and Steinbeck's Log From The Sea of Cortez. Neither one is chiefly about fly-fishing or about trout, but they're both written in a way that makes me re-think how I view the world. And they do both talk a good deal about fish, and fishing.

|

| Mayfly on my reel. Summer 2014, Maine. |

If the point of writing books about fish is to give techniques, or data, then we don't need many at all. But stories about fish and fishing are rarely about the taking of fish. More often they are about the states of mind that open up as we prepare to enter the water, or as we stand there in the river. Fishing is to such states of consciousness what kneeling is to prayer; the posture is perhaps not essential, but it is a bodily gesture that does something to prepare us to be open to a certain kind of experience. I won't belabor this point. Read my book if you really want me to go on about fishing and philosophy. For now, let me present some of my recommendations, plus the recommendations I've received:

On Nature

I teach environmental philosophy and ecology, so I begin with some orienting books.

Some Favorites

Classics

These have been recommended time and again. I'm not sure many people ever actually read the first two, though they become prized volumes in the libraries of anglers around the world.

Most Recommended

Fly-Tying

Places

One reason why there is so much writing about fishing is that fishers tend to be students of particular places. Yes, some people fish by indiscriminately approaching water and drowning hooked worms therein, but experience tends to cure most young anglers of that method. Fishing puts us into contact with what we cannot see (or cannot see well) under the water; experienced anglers learn to read the signs above the water and the place itself. We return to the same place as we return to beloved passages in books or to favorite songs, to know them better through repetition.

Other Frequent Recommendations

If I talk to a group of anglers about books for long enough, one or more of these will eventually be mentioned. Stylistically and in terms of content, they're quite different, but they all seem to speak to important moods and thoughts of anglers.

Other Recommendations

Most of these I don't know at all, so I'm not recommending them, just mentioning them. Of course, if you have more recommendations (or corrections), please feel free to add them to the comments section, below.

I'll conclude with a few other recommendations. First, when I've asked for recommendations about texts, a handful of people tell me "Tenkara." This isn't a text, but a kind of rod, and a method of fly-fishing. And yet people continue to say that word to me when I ask for texts. Why is that? I have a few guesses: there isn't a lot written about tenkara, but people who practice it have come to love its simplicity and grace. I'm not a tenkara fisher (yet) but I'm eager to learn. I have a feeling that tenkara, like so many spiritual practices or like some martial arts, is something that makes people feel they way great writing makes us feel: in it we transcend the immediacy of our environment.

Along those lines, one commenter on Facebook said this to me about my students: "Give them [a] fly rod and a stream and let them write [their] own story." There is wisdom here. It is one thing to read about waters, and quite another to enter the waters on one's own feet. Even so, I think it's important and wise to learn from those who've gone before us, too.

If you're interested in seeing some of my other book recommendations, have a look at this, this, and this.

Interview on SD Public Radio

Click here to listen to the whole interview.

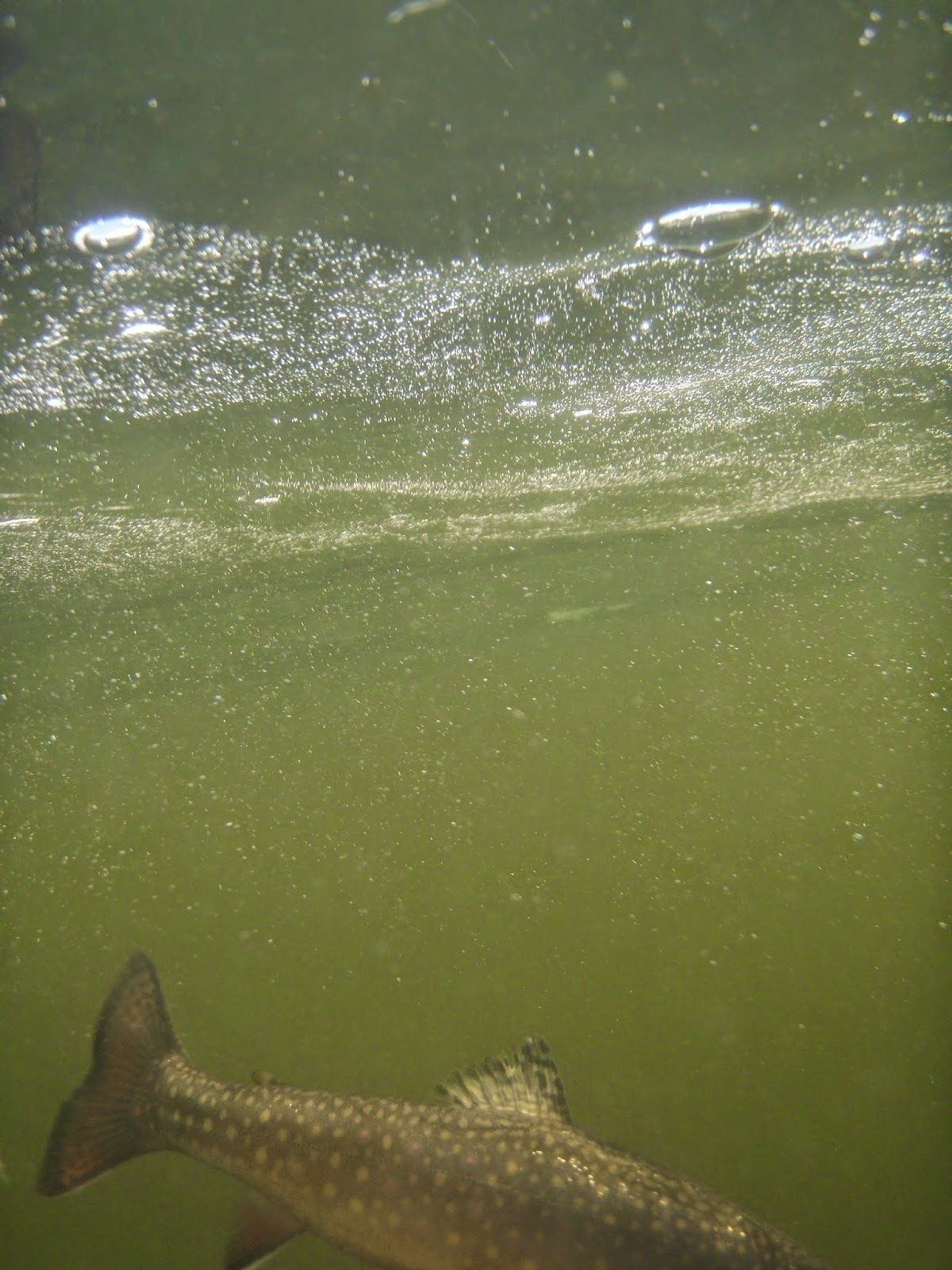

From My New Book: Brook Trout In The Tellico River

|

| Brook trout |

The passage is about the history of the Tellico River in eastern Tennessee. The Tellico was devastated a century ago by commercial logging. Attempts to restore the habitat and the indigenous wildlife have met with mixed results. The river still holds trout, but they are mostly western rainbow trout, not native brook trout. The rainbows, which are not native to the east coast or the Appalachians are simply easier to breed, which is what the state wants. Fish that are easy to breed are easy to stock, and stocked fish generate income.

You can read the passage here, and you can find the book here.

*****

I'm particularly happy with the photo here, because it's a photo of a free brook trout, one that is not attached to anyone's line, swimming away from me. It's hard to get such shots, but free-swimming brook trout really make me happy.

Why Does A Philosophy Professor Write About Trout?

To this question I have three brief replies, which I'll say more about later.

The first is that this book really is about those things, even if it won't appear to be so at first blush.

The second is that in fact, I think more philosophers should turn our attention to the matter of lived experience, to our technology, to our tools, and to our ways of knowing the world. It's not enough to know things about the world; we ought to ask just how we know the things we know, and how our tools and our very modes of life and habits affect that knowledge. And everything that hangs on that knowledge.

And for my third brief reply, I turn to Edward Mooney, who, in his introduction to Henry Bugbee's beautiful book, The Inward Morning, recalls a question Martin Heidegger asked Bugbee in August of 1955: “What occasion prompts philosophical reflection?”

Mooney writes that no doubt Heidegger “anticipated a flat American response. Yet he found his question returned in a Socratic reversal. Bugbee simply asked, echoing a Basho haiku, 'Could the sound of a fish leaping at a fly at dawn suffice?'”

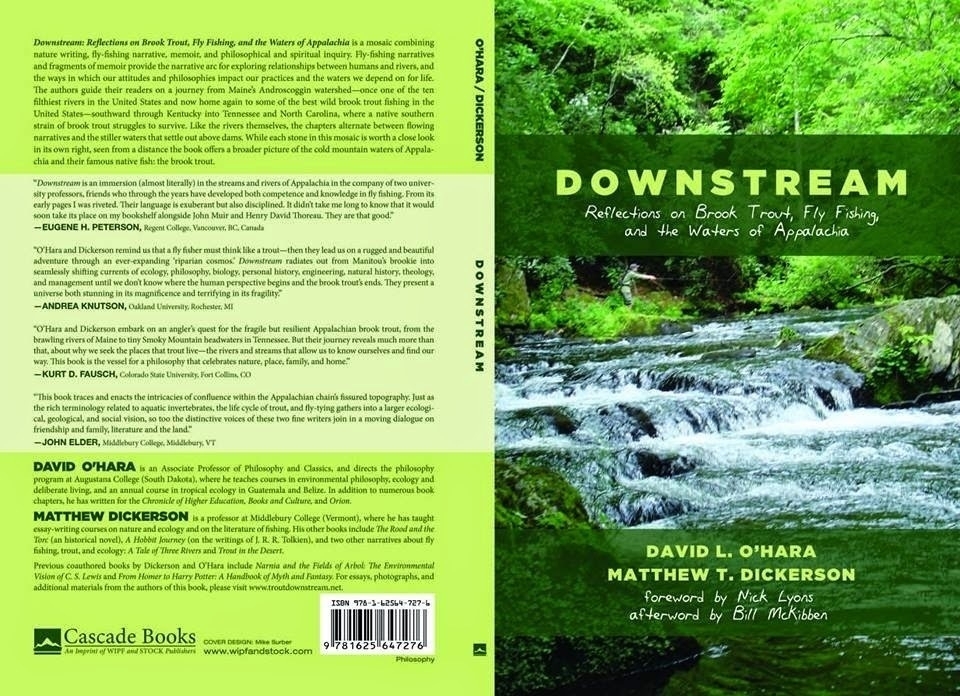

Downstream: My New Book On Brook Trout and Appalachian Ecology

It is now listed on Amazon as well, though not yet in stock there.

I'm very grateful for the foreword by Nick Lyons, the afterword by Bill McKibben, and the kind words offered by such a wide range of brilliant scholars of theology, literature, and science, like Eugene Peterson, Andrea Knutson, Kurt Fausch, and John Elder.

Green Mountain Creek

Matt and I stand thigh-deep in one of the small streams that

tumble down the eastern slopes of the Green Mountains. Many of those

streams, including this one, have carved steep gorges over the

millennia. As the water falls it strips away the sand and loam, leaving

a course choked with jumbled boulders.

Matt and I stand thigh-deep in one of the small streams that

tumble down the eastern slopes of the Green Mountains. Many of those

streams, including this one, have carved steep gorges over the

millennia. As the water falls it strips away the sand and loam, leaving

a course choked with jumbled boulders.Every year a few more trees, undercut by the current, tip over into the stream, where they lodge against the boulders and form temporary dams. As the water flows over those dams it digs deep plunge pools, bubbling and swirling for a few feet, then quickly settling into swift, clear, tea-colored glassy pools. The water slows only long enough to catch its breath before it plunges again, stair-stepping down the mountain, moving the mountain itself downstream one grain of sand at a time.

Beside us, logs carpeted in moss play host to uncounted lives of plants and animals. Trees reach their branches down into the cleft cut by the river, searching for sunlight wherever they can in this steep gorge. Small flies whirl restlessly across our vision. Their blue wings and olive bodies seem an unnecessary and extravagant dash of color on something so small, so ephemeral.

Vermont is named for the greenness of its mountains, or les monts verts as the first French settlers called these ancient hills. One of the rivers nearby is called the Lemon Fair, its name preserving the French sounds in misplaced English words. A sweeping glance would call this place green, but it only takes a moment of slowing down to really look before you see all the rainbow represented here.

Much of the color is underwater, on the scales of the fine-featured trout that fin the current before us. The native brook trout are dappled a vermiculated green above, fading to pale bellies below. Their fins are slashed with bright red and white. The rainbow trout, imported from the west coast, iridesce when a beam of sunlight finds its way down through the leaves and the water. The young brown trout - far from their native Europe - shine like salmon. Under the rocks small tan sculpin harvest tiny invertebrate meals.

Gray stones slide slower than glaciers down the bank, moving imperceptibly and irresistibly toward the sea. On the bank, seven tiny mushrooms stand up, no taller than my thumb, their caps bright orange like yearling efts.

It is a perfect day. We are grateful to receive it, grateful to be here, to stand in these waters as their life flows around us.

*****

|

| My friends Bill and Brian paddle the Concord River, as Thoreau once did. |

“[F]ishers can be natural historians and waterside contemplatives par excellence."

Anecdotally, I find that hunting and fishing have made me less of a carnivore, and increasingly concerned with animal flourishing. (The quote from Stephanie Mills is found in Epicurean Simplicity, published in Washington, Covelo, and London: Island Press/Shearwater Books, 2002 p.125.)

*****

Books Worth Reading

I'm reluctant to make book recommendations because I think what you read should have some connection to what you care about and what you've already read. In general, my recommendations are these:

First, I agree with what C.S. Lewis once said:* it's good to read old books. Old books and books written by people who are not like us have a remarkable power of helping us to see the world with fresh eyes.

Second, let your reading grow organically. If you liked a book you read, let it lead you to the next book you read. Often, books name their connections to other books. Or authors will name those connections, dependencies, and appreciations. The first time I read Lewis's Out of the Silent Planet, I missed the fact that the preface named H.G. Wells and that the afterword referred to Bernardus Silvestris. When I read it again as an adult, I caught those obvious references and let them lead me to other books.**

Third, I recommend learning the classics. That's an intentionally vague term, and I use it to mean that it's good to know those books that have given your culture its vocabulary. People who have stories in common have enriched possibilities for conversation. One of my favorite Star Trek episodes explored this idea, and it appealed to me because I believe that it's not far from how language really grows. If you need a place to start, check out one of the various lists of "great books" floating around out there. For instance this one, or this one.

With all that being said, if you're still interested in what I'm reading, here are some older titles I've enjoyed in the last year or so:

* Lewis said this in his introduction to Athanasius' On The Incarnation (which, by the way, is now available from SVS Press in a dual-language edition, Greek on one page, English on the facing page.)

** There are two excellent books on Lewis' "Space Trilogy" or (as I think it should be called) "Ransom Trilogy": This one by Sanford Schwartz, and this one by David Downing.

Do Philosophy Classes Have "Labs"?

When I was preparing to go to grad school I was torn between two choices: Ph.D. in marine/riparian biology, or Ph.D. in philosophy? I love fish, aquatic invertebrates,

(well, most of them, anyway) and the environments they live in. Wouldn't it be great to make freestone streams and tidal pools into my classrooms?

But I also love philosophy. Philosophy has connections to every other discipline; it offers a unique perspective on human activities; and it promotes some of the most interesting and fruitful conversations I know of. (Yes, I admit some professional bias here, and don't begrudge others a similar bias towards what they love.) Philosophy classes take on questions about truth, value, meaning, religion, justice, science, language, reason, history, relationships, and much more. It can be very difficult, but there's usually a huge payoff for the effort you put into it.

Now that I teach philosophy, I often find myself lurking around the biology department at my school, to read their journals, to talk with the professors there (who patiently put up with my presence there), and to eye their labs with envy.

Now, I think bio labs are great places, but it's not the places themselves that I most like. It's rather the idea of the place. Labs are spaces set apart for learning by experience. We have labs for the sciences, and we have labs for the arts as well (though we usually call those "studios"). In the social sciences they use labs for observing human activities, and foreign languages have (or ought to have) labs for practicing language. Writers have workshops, historians have museums and archives, and other disciplines have internships.

Philosophy, unlike all these other disciplines, does not appear to have any labs at all. At least, not at first glance.

Partly this is due to the reflective nature of philosophy: philosophers have often understood our discipline as a step back from experience in order to gain a cool, disinterested view of the world. To some degree, we still think that, but that idea of having a privileged access to reality through the use of the right kind of language, or through a scientific worldview, has fallen under suspicion. Pace Descartes, we don't necessarily understand the world better by turning completely away from it.

Contrary to popular opinion, "philosophy" is not a synonym for "opinion." Nor is it a synonym for "doctrines." Philosophy has grown and changed quite a lot in the last few centuries, which means that is not always easy to define. One thing that is common to all philosophers, however, is that philosophy is an activity. Doing philosophy is not the mere rehearsal of past views, nor is it merely an attempt to present our already established opinions in clearer or more persuasive language.

Philosophers do, in fact, set aside spaces and times for practicing philosophy. One important kind of lab philosophers have is the seminar, which has its roots in Plato's practice of philosophy. Whatever else we might say about Plato, he knew how important good conversation is to advancing philosophy. In his dialogues, Plato uses conversation to illustrate two points: first, we need to spend at least some of our time in serious, sustained conversation and reflection with others. Second, when we do so, we need to follow the argument where it leads and not just where we want it to go.

|

| A brook trout I photographed in Maine. |

*********************

[Images: Raphael's "School of Athens," showing famous Greek philosophers "at work"; two mayflies photgraphed in the summer of 2009 in Gravenhurst, Ontario; one of the tributaries to Lake Muskoka in Ontario; a brook trout photographed on the Magalloway River in Maine, 2009 while fishing and doing some research with Matt Dickerson. The Raphael image is in the public domain; the others are my own photos. I think mayflies are especially lovely creatures. The adult stage shown above is a very brief period of their lives; most of their lives are spent underwater, and their appearance is quite different then from what it is as adults.]