C.S. Lewis

- Grammar. This is the study of words, and especially:

- how definitions work, so that we can "come to terms" with one another; and

- how words are assembled into meaningful sentences or propositions.

- Logic. This is the study of the structure of arguments:

- how to assemble propositions into arguments; and

- how to draw proper conclusions from those propositions without error.

- Rhetoric. This is the study of the proper use of arguments:

- how to use arguments to persuade others; and

- how and when to persuade without misleading people.

- Arithmetic. This is the study of number.

- Geometry. This is the study of number in space.

- Music. This is the study of number in time.

- Astronomy. This is the study of number in space and time.

- Virginia Woolf, Mrs. Dalloway. (Mixed feelings about this one. My mind enjoyed it more than my aesthetic sense did, if that makes sense.)

- John Steinbeck, Cannery Row and Of Mice and Men. (I discovered Steinbeck late in life, thanks to a friend's recommendation. I've also recently read his Log From The Sea of Cortez and Travels With Charley In Search Of America. I think these two will forever shape me as a writer.)

- Graham Greene, Our Man In Havana, The Quiet American, The Honorary Consul, Travels With My Aunt, The Power And The Glory. (I will let the number of titles speak for itself.)

- Alan Paton, Cry, The Beloved Country. (I was surprised by how contemporary this old book felt, and by how relevant to America an African book could feel.)

- The Táin. Because I have a thing for reading really old books, and this is one of the oldest from Europe.

- China Miéville, Kraken. (London. Magical realism. Bizarre and witty.)

- J. Mark Bertrand, Back On Murder (I don't read many detective novels, but I really enjoy Bertrand's prose.)

- Cormac McCarthy, The Road. (The final lines spoke to my salvelinus fontinalis -loving heart.)

- David James Duncan, The River Why (I've re-read this one a few times. If you like trout and philosophy, you might like this book.)

- Mary Karr, Lit. (Third in a series of memoirs. Some of the best storytelling I've read in a long time. Brilliant insights into addiction, love, and prayer.)

∞

Perennial Thinking in Education, Ag, and Culture - Lori Walsh interviews Bill Vitek and me on SDPB

Last week I had the pleasure of hosting Bill Vitek at Augustana University. Together we taught a philosophy class and a biology class, he spoke in our chapel, and he gave a lecture on campus.

One of the persistent themes of his work is the connection between culture and agriculture: the two shape one another.

Another theme that is related to the first: we all eat, and we all think, and eating and thinking indluence one another.

A third theme: we tend to focus our thinking on the annual or the short-term, neglecting the perennial and long-term. having spent a few days with Bill, I'm now reflecting on what I find one of the most provocative parts of his work: what would it mean to shift from thinking of education as an annual crop to thinking of it as a perennial? Currently we begin planting at the beginning of the season, and we expect to harvest grades and graduates at the end of the term.

What if we thought of education in the way we think about caring for perennials? What if we considered school to be more like the planting of trees than like the planting of corn? Or what if we figured out a way (as they are doing at the Land Institute, where Bill is a collaborator with Wes Jackson - here's a link to one of their co-edited books) to give our annual crops perennial roots?

I have a lot of work and thinking and cultivating ahead of me, so I won't answer those questions here. If you have taken my classes, you already know how I have been working on this over the years (think of how I speak about grades and exams in my classes, for instance). And if you've read my books (like my book on C.S. Lewis' environmental thought, or my book on brook trout as indicators of both natural ecology and cultural ecology), you know I'm working on these ideas, and they will require long cultivation. I'm okay with that.

For now, feel free to listen to Bill and me as we are interviewed by Lori Walsh on South Dakota Public Radio.

One of the persistent themes of his work is the connection between culture and agriculture: the two shape one another.

|

| A bit of prairie, with perennial grasses. |

Another theme that is related to the first: we all eat, and we all think, and eating and thinking indluence one another.

A third theme: we tend to focus our thinking on the annual or the short-term, neglecting the perennial and long-term. having spent a few days with Bill, I'm now reflecting on what I find one of the most provocative parts of his work: what would it mean to shift from thinking of education as an annual crop to thinking of it as a perennial? Currently we begin planting at the beginning of the season, and we expect to harvest grades and graduates at the end of the term.

What if we thought of education in the way we think about caring for perennials? What if we considered school to be more like the planting of trees than like the planting of corn? Or what if we figured out a way (as they are doing at the Land Institute, where Bill is a collaborator with Wes Jackson - here's a link to one of their co-edited books) to give our annual crops perennial roots?

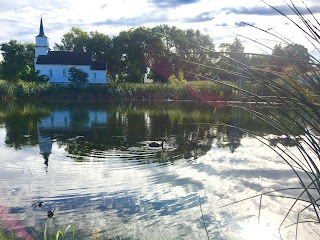

|

| A view of the Augustana University campus, with historic buildings. |

I have a lot of work and thinking and cultivating ahead of me, so I won't answer those questions here. If you have taken my classes, you already know how I have been working on this over the years (think of how I speak about grades and exams in my classes, for instance). And if you've read my books (like my book on C.S. Lewis' environmental thought, or my book on brook trout as indicators of both natural ecology and cultural ecology), you know I'm working on these ideas, and they will require long cultivation. I'm okay with that.

For now, feel free to listen to Bill and me as we are interviewed by Lori Walsh on South Dakota Public Radio.

∞

Books Worth Reading

Occasionally I post on this blog a list of books I’ve been reading. It’s a way of sharing what I’ve learned, and that process of reviewing what I’ve read helps me to deepen my memory.

This post will be a little different. At the end I’ll share some new books I’ve been reading recently, but I’m going to start with some older books.

Three Older Books

China in Ten Words (Yu Hua, 2012; Allan H. Barr, translator) This is not very old, but it gives a history of some of the ideas that shape modern China. Each chapter considers one word and the way it exemplifies or illustrates something important about Chinese culture, especially since the cultural revolution. This has helped me to understand my Chinese students better, and it gives me more insight into Chinese politics, international policy, and economics. Yu Hua is a novelist, and his stories make for smooth, inviting reading. This spring I was teaching a class with students from ten different countries. At one point, one of my students from another country asked me why American schools are so concerned with plagiarism. Most of the other international students nodded in agreement. It was a helpful reminder that our American notions of intellectual property and academic integrity are tied to our idea that we are first and foremost individual agents, and it is individuals who bear responsibility for their actions and who gain the rewards for their achievements. Whether that’s true or not is debatable, but we don’t seem to have escaped from the Cartesian notion of the radical individual, the Protestant pietism that emphasizes the fall and redemption of the individual soul, or the Jeffersonian idea that rights and happiness are expressed in the individual. Over the last fifty years, China has shifted in that direction, to be sure, but China is still deeply in touch with both its Confucian sense of community and the aftereffects of its century of revolutions.

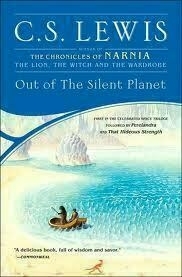

Out of the Silent Planet (C.S. Lewis, 1938) This is Lewis’ sci-fi novel about Mars. But of course no novel is ever about Mars; mostly, novels about Mars are about this planet and its inhabitants. Along with Lewis’ essay “Religion and Rocketry” (originally published as “Will We Lose God In Outer Space?”) this novel is important because it is a subtle invitation to examination of why we want to go to Mars in the first place. For me, it is one of the most important works of the ethics of space exploration, for a number of reasons. If you want all my reasons, feel free to buy my book on C.S. Lewis. Here’s one reason: most alien-encounter stories we write begin with the assumption that the aliens are the bad guys. Lewis wants us to consider that if we find our planet has gotten too uncomfortable for us, maybe we’re not the protagonists of this story.

The Way We Live Now (Anthony Trollope, 1875) This is about the 2016 election in the U.S. — but it was written in the middle of the 19th century in the U.K. I read this back in the summer of 2016, and I thought, “Oh, D.T. is going to win the election.” I won’t say it’s prescient, because it’s not explicitly about any future event, but Trollope does a good job of showing us what motivates us, how shallow those motives can be, what we will sacrifice to achieve them, and other perils of modern political life.

I’ll end this section with three unrelated books that nevertheless seem related to me: Charles Dickens’s Bleak House; Herman Melville’s Bartleby the Scrivener; and William Faulkner’s Go Down, Moses. Two things tie these books together for me: all were recommended by friends, and all have something to do with chancery courts. I have liked Melville for a long time, and I rarely regard time spent in his prose as time wasted. Dickens and Faulkner I like far less. I read Dickens as a portrait of his time, and time in his pages is like cultural archaeology. But it’s also like listening to someone make a short story into a long one while you’re trying to get to your next appointment. Faulkner is not at all like Dickens in that regard. He condenses his ideas so much that everything needs to be unpacked. Reading Faulkner quickly is unsatisfying; reading Faulkner slowly is tiring. For different reasons, Faulkner and Dickens are both tedious reads for me. Both of them make me lose the plot, one because he’s too fast, the other because he’s too slow. But in neither case is this a flaw in the author; I’m just highlighting a difference between the way they think and the way I think. Good friends recommended them, and that matters: reading what others care about can be a work of love and of fostering mutual understanding.

Should We Still Be Reading Books?

I read a lot of books each year. Usually when I tell people how many books I read, I am met with wide-eyed disbelief, so I won’t bother to tell you how many I read in a year. Instead, I will invite you to consider the importance of books. Recently I asked a group of graduate students about their reading habits. Some said they read about a dozen books a year in addition to required reading for their classes. I thought that was pretty good, considering how busy they are. But a few told me they get all their information online, mostly in condensed form through synopses and through Twitter. I don’t disparage the value of reading quickly and of foraging in the rich banquet hall of small parcels of always-ready information that our new technologies afford us. We live in rich times, indeed. I only hope that those graduate students will supplement their diet of fast reading with some slow reading and even with some fasting for contemplation and digestion.

There are some problems with books, to be sure. For one thing, they take a long time to read, and some of that reading (as with Dickens) can be slow going. For another: they take a long time to write. A third thing: the barriers to publication mean it’s easier to find books by people with connections to publishers than books by rural writers, non-English writers, etc.

But books are durable. I started writing this blog post on my tablet, and then the battery died. That never happens with books. Books are resilient, or super-resilient. Consider the way John Steinbeck’s The Moon Is Down spread across Europe during the Second World War. We think social media are fast today, but Steinbeck’s propaganda novel spread rapidly because each time someone read it they made the decision whether to copy it, and many people copied and translated it. Decisions like that are much costlier than retweeting something you glanced at, and so they carry much more weight and value. And once a book like that is copied, it’s very hard to delete it. How many books have been written about both the danger books pose to people clinging to power? And then there’s that old question about which books you’d bring to a desert island; how many of you would choose to bring a laptop or a tablet? The salt air and heat would kill it quickly even if you had solar panels to recharge it. Books are hard to beat.

A Few Recent and Current Reads

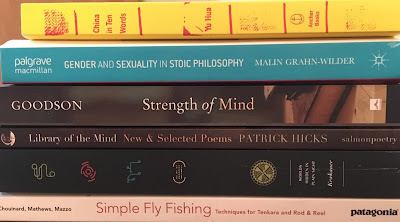

I’ll wrap up with a few recent reads, all of which I recommend, and all of which I’ll post here with minimal commentary:

Edward F. Mooney, Excursions with Thoreau: Philosophy, Poetry, Religion. (2015) Someday I would like to write like Ed Mooney. His book on Henry Bugbee was a confirmation that it’s acceptable to write academic philosophy in a way that is both clear and readable. (James Hatley did this for me in some of his articles, too. I’m grateful to both of them for that.) Now I’m very much looking forward to Mooney’s next book, Living Philosophy in Kierkegaard, Melville, and Others: Intersections of Literature, Philosophy, and Religion.

Patrick Hicks, Library of the Mind: New & Selected Poems. If you’re not reading poetry, what has gone wrong with your life? Never mind, don’t try to answer that. Instead, just read good poetry. Here’s an excellent place to start. Each page makes me slow down and collect myself again.

Malin Grahn-Wilder, Gender and Sexuality in Stoic Philosophy. I teach ancient and medieval philosophy, and I find books like this keep me sharp. The organization of the book is excellent, and so is the content. This is a nicely written history of ideas, and a useful resource for scholars.

Jacob Goodson, Strength of Mind: Courage, Hope, Freedom, Knowledge. I’ve known Jacob for a few years, and I like everything he writes. This is no exception. Jacob’s an excellent teacher with an encyclopedic mind. I have the good fortune of spending time with him in person each year, and those conversations become miniature seminars that leave me feeling refreshed and energized; he tills the soil of the mind. So you should buy this book and enjoy it. But I’m especially looking forward to his next collaboration with Brad Elliott Stone, Introducing Prophetic Pragmatism: A Dialogue on Hope, the Philosophy of Race, and the Spiritual Blues. That will be out later this year.

Evan Selinger and Brett Frischmann, Re-Engineering Humanity. This is one of a small number of books that I’ve gone back to multiple times. Selinger is worth following on Twitter for a daily dose of sharp observations on how we are letting technology race ahead of ethics. Once you’ve looked at what he posts there, you’ll find you’re either ready to check out of digital life altogether, or to go into the deep dive of this book so you can get a better handle on what to do next.

Yvon Chouinard, Craig Mathews, and Mauro Mazzo, Simple Fly Fishing: Techniques for Tenkara and Rod & Reel. Revised second edition, with paintings by James Prosek. Come for the zen-like techniques, stay for the beauty of each page, and take the time to read those small things like why Chouinard mapped several unmapped mountain routes, then burned the maps. “But standing around the campfire one day, we decided to burn our notes…There need to be a few places left on this crowded planet where ‘here be dragons’ still defines the unknown regions of maps. Then I went fishing.” If you follow me on social media, you know I write about trout and salmon. You might also know, if you pay close attention, that I love the places that the fish live, I love swimming with the fish, and I love the things and people they’re connected to. But the more I fish, the less I feel the need to fish, and the happier I am being near the fish. Tenkara rods are a very old way of being still with the fish.

David C. Krakauer, ed. Worlds Hidden In Plain Sight: The Evolving Idea of Complexity at the Santa Fe Institute 1984-2019. This is one I’m working through slowly, and I’m not reading it cover-to-cover. The organization of this book makes it one that invites a bit of flaneurism, reading deeply and thoughtfully, but in the manner of what Thoreau calls “sauntering”: not a linear, business-like drive to the finish line, but a walk without purpose other than to see what is there. This is one of the best kinds of learning. The book is, indirectly, about the importance of cross-disciplinary reading; the importance of philosophy of science for everything from understanding markets to climate change; and the helpful and constant reminder we don’t know enough about the things we quantify, even though we talk about the quantification with such authority. The book is priced at about ten bucks, but it's worth far more than that.

Is there something better than reading well-considered words? Perhaps, but all of these books have so far been well worth my while. I hope you have good books in your life as well.

This post will be a little different. At the end I’ll share some new books I’ve been reading recently, but I’m going to start with some older books.

Three Older Books

China in Ten Words (Yu Hua, 2012; Allan H. Barr, translator) This is not very old, but it gives a history of some of the ideas that shape modern China. Each chapter considers one word and the way it exemplifies or illustrates something important about Chinese culture, especially since the cultural revolution. This has helped me to understand my Chinese students better, and it gives me more insight into Chinese politics, international policy, and economics. Yu Hua is a novelist, and his stories make for smooth, inviting reading. This spring I was teaching a class with students from ten different countries. At one point, one of my students from another country asked me why American schools are so concerned with plagiarism. Most of the other international students nodded in agreement. It was a helpful reminder that our American notions of intellectual property and academic integrity are tied to our idea that we are first and foremost individual agents, and it is individuals who bear responsibility for their actions and who gain the rewards for their achievements. Whether that’s true or not is debatable, but we don’t seem to have escaped from the Cartesian notion of the radical individual, the Protestant pietism that emphasizes the fall and redemption of the individual soul, or the Jeffersonian idea that rights and happiness are expressed in the individual. Over the last fifty years, China has shifted in that direction, to be sure, but China is still deeply in touch with both its Confucian sense of community and the aftereffects of its century of revolutions.

Out of the Silent Planet (C.S. Lewis, 1938) This is Lewis’ sci-fi novel about Mars. But of course no novel is ever about Mars; mostly, novels about Mars are about this planet and its inhabitants. Along with Lewis’ essay “Religion and Rocketry” (originally published as “Will We Lose God In Outer Space?”) this novel is important because it is a subtle invitation to examination of why we want to go to Mars in the first place. For me, it is one of the most important works of the ethics of space exploration, for a number of reasons. If you want all my reasons, feel free to buy my book on C.S. Lewis. Here’s one reason: most alien-encounter stories we write begin with the assumption that the aliens are the bad guys. Lewis wants us to consider that if we find our planet has gotten too uncomfortable for us, maybe we’re not the protagonists of this story.

The Way We Live Now (Anthony Trollope, 1875) This is about the 2016 election in the U.S. — but it was written in the middle of the 19th century in the U.K. I read this back in the summer of 2016, and I thought, “Oh, D.T. is going to win the election.” I won’t say it’s prescient, because it’s not explicitly about any future event, but Trollope does a good job of showing us what motivates us, how shallow those motives can be, what we will sacrifice to achieve them, and other perils of modern political life.

I’ll end this section with three unrelated books that nevertheless seem related to me: Charles Dickens’s Bleak House; Herman Melville’s Bartleby the Scrivener; and William Faulkner’s Go Down, Moses. Two things tie these books together for me: all were recommended by friends, and all have something to do with chancery courts. I have liked Melville for a long time, and I rarely regard time spent in his prose as time wasted. Dickens and Faulkner I like far less. I read Dickens as a portrait of his time, and time in his pages is like cultural archaeology. But it’s also like listening to someone make a short story into a long one while you’re trying to get to your next appointment. Faulkner is not at all like Dickens in that regard. He condenses his ideas so much that everything needs to be unpacked. Reading Faulkner quickly is unsatisfying; reading Faulkner slowly is tiring. For different reasons, Faulkner and Dickens are both tedious reads for me. Both of them make me lose the plot, one because he’s too fast, the other because he’s too slow. But in neither case is this a flaw in the author; I’m just highlighting a difference between the way they think and the way I think. Good friends recommended them, and that matters: reading what others care about can be a work of love and of fostering mutual understanding.

Should We Still Be Reading Books?

I read a lot of books each year. Usually when I tell people how many books I read, I am met with wide-eyed disbelief, so I won’t bother to tell you how many I read in a year. Instead, I will invite you to consider the importance of books. Recently I asked a group of graduate students about their reading habits. Some said they read about a dozen books a year in addition to required reading for their classes. I thought that was pretty good, considering how busy they are. But a few told me they get all their information online, mostly in condensed form through synopses and through Twitter. I don’t disparage the value of reading quickly and of foraging in the rich banquet hall of small parcels of always-ready information that our new technologies afford us. We live in rich times, indeed. I only hope that those graduate students will supplement their diet of fast reading with some slow reading and even with some fasting for contemplation and digestion.

There are some problems with books, to be sure. For one thing, they take a long time to read, and some of that reading (as with Dickens) can be slow going. For another: they take a long time to write. A third thing: the barriers to publication mean it’s easier to find books by people with connections to publishers than books by rural writers, non-English writers, etc.

But books are durable. I started writing this blog post on my tablet, and then the battery died. That never happens with books. Books are resilient, or super-resilient. Consider the way John Steinbeck’s The Moon Is Down spread across Europe during the Second World War. We think social media are fast today, but Steinbeck’s propaganda novel spread rapidly because each time someone read it they made the decision whether to copy it, and many people copied and translated it. Decisions like that are much costlier than retweeting something you glanced at, and so they carry much more weight and value. And once a book like that is copied, it’s very hard to delete it. How many books have been written about both the danger books pose to people clinging to power? And then there’s that old question about which books you’d bring to a desert island; how many of you would choose to bring a laptop or a tablet? The salt air and heat would kill it quickly even if you had solar panels to recharge it. Books are hard to beat.

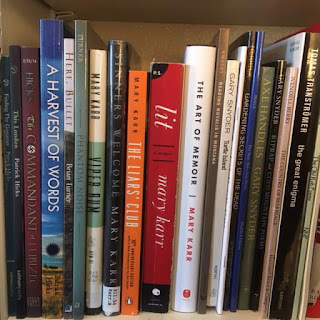

|

| Some of my recent reads. |

A Few Recent and Current Reads

I’ll wrap up with a few recent reads, all of which I recommend, and all of which I’ll post here with minimal commentary:

Edward F. Mooney, Excursions with Thoreau: Philosophy, Poetry, Religion. (2015) Someday I would like to write like Ed Mooney. His book on Henry Bugbee was a confirmation that it’s acceptable to write academic philosophy in a way that is both clear and readable. (James Hatley did this for me in some of his articles, too. I’m grateful to both of them for that.) Now I’m very much looking forward to Mooney’s next book, Living Philosophy in Kierkegaard, Melville, and Others: Intersections of Literature, Philosophy, and Religion.

Patrick Hicks, Library of the Mind: New & Selected Poems. If you’re not reading poetry, what has gone wrong with your life? Never mind, don’t try to answer that. Instead, just read good poetry. Here’s an excellent place to start. Each page makes me slow down and collect myself again.

Malin Grahn-Wilder, Gender and Sexuality in Stoic Philosophy. I teach ancient and medieval philosophy, and I find books like this keep me sharp. The organization of the book is excellent, and so is the content. This is a nicely written history of ideas, and a useful resource for scholars.

Jacob Goodson, Strength of Mind: Courage, Hope, Freedom, Knowledge. I’ve known Jacob for a few years, and I like everything he writes. This is no exception. Jacob’s an excellent teacher with an encyclopedic mind. I have the good fortune of spending time with him in person each year, and those conversations become miniature seminars that leave me feeling refreshed and energized; he tills the soil of the mind. So you should buy this book and enjoy it. But I’m especially looking forward to his next collaboration with Brad Elliott Stone, Introducing Prophetic Pragmatism: A Dialogue on Hope, the Philosophy of Race, and the Spiritual Blues. That will be out later this year.

Evan Selinger and Brett Frischmann, Re-Engineering Humanity. This is one of a small number of books that I’ve gone back to multiple times. Selinger is worth following on Twitter for a daily dose of sharp observations on how we are letting technology race ahead of ethics. Once you’ve looked at what he posts there, you’ll find you’re either ready to check out of digital life altogether, or to go into the deep dive of this book so you can get a better handle on what to do next.

Yvon Chouinard, Craig Mathews, and Mauro Mazzo, Simple Fly Fishing: Techniques for Tenkara and Rod & Reel. Revised second edition, with paintings by James Prosek. Come for the zen-like techniques, stay for the beauty of each page, and take the time to read those small things like why Chouinard mapped several unmapped mountain routes, then burned the maps. “But standing around the campfire one day, we decided to burn our notes…There need to be a few places left on this crowded planet where ‘here be dragons’ still defines the unknown regions of maps. Then I went fishing.” If you follow me on social media, you know I write about trout and salmon. You might also know, if you pay close attention, that I love the places that the fish live, I love swimming with the fish, and I love the things and people they’re connected to. But the more I fish, the less I feel the need to fish, and the happier I am being near the fish. Tenkara rods are a very old way of being still with the fish.

David C. Krakauer, ed. Worlds Hidden In Plain Sight: The Evolving Idea of Complexity at the Santa Fe Institute 1984-2019. This is one I’m working through slowly, and I’m not reading it cover-to-cover. The organization of this book makes it one that invites a bit of flaneurism, reading deeply and thoughtfully, but in the manner of what Thoreau calls “sauntering”: not a linear, business-like drive to the finish line, but a walk without purpose other than to see what is there. This is one of the best kinds of learning. The book is, indirectly, about the importance of cross-disciplinary reading; the importance of philosophy of science for everything from understanding markets to climate change; and the helpful and constant reminder we don’t know enough about the things we quantify, even though we talk about the quantification with such authority. The book is priced at about ten bucks, but it's worth far more than that.

Is there something better than reading well-considered words? Perhaps, but all of these books have so far been well worth my while. I hope you have good books in your life as well.

*****

In the interest of full disclosure: I know a number of these authors, and I'm glad to know them, and I'm glad to tell you about their books. And I'm not paid a thing to tell you about their books; I just get the satisfaction of sharing good things with others.

∞

How I Write - A Quick Reply To A Young Writer

This morning I came to the office to find an email from a student at another college. They were writing to ask advice for a young writer. In my own college years writing often felt like a challenge to overcome, especially when I was writing simply to satisfy a course requirement. After I graduated, I discovered that writing helped me to think and to communicate more clearly. For the last few decades, I've written more and more, and in general I find it to be a pleasant activity. I lost my ability to write for a little while after I was injured three years ago, and the process of re-learning it has been good for my mind and my spirit alike.

The email I received was polite and kind, and I thought it worth my time to write a short reply even though I had other urgent tasks to get to. I never want to let the truly important abdicate to the merely urgent; tasks that clamor are not always the best tasks, and those opportunities that speak softly are not always the least valuable. Here's the email I received, and my reply. I've edited the email I received to protect the author's privacy and to highlight their question and some of my main points in boldface. I've edited my reply slightly as well, since I've got a few minutes to do so.

If you've got good advice for my correspondent, feel free to offer your advice in the comments below. (I'll delete advertisements, though.)

Dear Friend,

Thanks for your thoughtful question. I'm not sure I've got a one-size-fits-all process, but I'm happy to share what I've learned and what I do. I've only got time for a short reply this morning, so apologies in advance for the brevity of this note. I have some students coming by in a few minutes and I like to try to be present for those who are right in front of me as much as possible. I suppose it's sort of a spiritual practice for me, that "being present." The alternative (for me, anyway) is to spend too much of my time not being present, which usually takes the form of stress and anxiety about that which is geographically or chronologically distant. Anyway, while my students aren't here, I'm regarding this email from you as your "presence" in my office, so let's talk about writing...

...which I suppose we've already begun doing. For me, one of the most helpful things has been making sure not to regard writing as an optional exercise. (It's too easy for me to let the urgent crowd out the important.) Writing matters to me because it helps me to think and it helps me to be in conversation with others. If I don't give it at least a little of my time - on a regular basis, that is - then my ability to write begins to atrophy. Disciplines that matter - the ones that are most connected to our best loves - should be treated like respiration; they need to be regular and constant. If writing is a matter of loving your neighbor for you, then write regularly, just like you breathe regularly.

Of course, the metaphor breaks down, because we breathe involuntarily and always, whereas we only write occasionally. But it's at least a partly useful metaphor. Because I want to be ready to write, I keep a paper notebook in my pocket all the time, remembering the words from one of the Narnia stories (Prince Caspian, maybe?) Hmm. Let's see. Yes, here it is:

Yes, it was Prince Caspian. And here's one of my other tricks: I write after each book I read. With each book, I take time to jot down a few words and a few lines that really mattered to me in that book. Then, when I want quick access to those words, I've got them all in a single file on my computer, and I can search for the word "ink" or "scholar" and up comes this quote. My file of quotations from books is now 130 pages long. (Don't despair - I've been adding to it for 20 years!) It's a tremendous resource for writing, and it helps me to remember what I read and where I read it.

Two more quick things, since I've got to go:

1) My graduate school faculty told me that writing a 300-page dissertation seemed like a lot, but if I thought of it as a page a day for a year, it would seem much smaller, and much easier. They were right.

2) I find it helpful to write more than one thing at a time. I'll work on one thing for a while - maybe only a few minutes a day - and then I find my mind is tired of writing and thinking about that subject. So I will turn to another task, and I often find I have new energy. Oddly, I wrote my first book while I was also writing my dissertation. I'd write the doctoral thesis during the day, and then, at night, I'd write the book as a way of distracting my mind and relaxing. Now I find that if I'm working on only one thing I feel great stress. Will I finish it? What if I mess it up? These questions haunt me. But when I have many writing projects ongoing, I don't mind it very much if I run into a wall of writer's block on one of them. True story: I have written several books that I will likely never publish, and I have half-written hundreds of articles and books that I may never publish. But each one is still on my computer, and I often return to those half-written pieces to scavenge a few footnotes or paragraphs or choice words. The unfinished tasks aren't on the scrap heap; they're unpolished gems in my store-room just waiting to be set in a new piece of jewelry. I'm not ashamed of them even though I don't wear them in public; they're treasures even though most people will never see them.

I hope this helps. Keep at it! Writing has been a great source of food for my mind and a great nourishment to my convivial conversations as well. I hope you find it to be of similar benefit.

All good things,

Dave

P.S. Here are a few other things I've written about writing, and teaching writing, and the role of nature in teaching me how to write.

The email I received was polite and kind, and I thought it worth my time to write a short reply even though I had other urgent tasks to get to. I never want to let the truly important abdicate to the merely urgent; tasks that clamor are not always the best tasks, and those opportunities that speak softly are not always the least valuable. Here's the email I received, and my reply. I've edited the email I received to protect the author's privacy and to highlight their question and some of my main points in boldface. I've edited my reply slightly as well, since I've got a few minutes to do so.

If you've got good advice for my correspondent, feel free to offer your advice in the comments below. (I'll delete advertisements, though.)

Dr. O'Hara,

I'm emailing you on a rather odd premise. I am a second-year student [in] college, and an avid follower of yours on Twitter. Over the course of about six months I have admired your work from afar. I would like to say your passion not only for your students, but your work, is nothing less than inspiring. That being said -- without taking up too much of your time -- I would like to ask for your advice. I know that you have written and contributed to many books. I have started one of my own, and would like to know how you go about the process of writing? I know it is a rather vague question, but I am just getting to about seven thousand words and fifty plus seems daunting. Do you have any advice?

Again, I am sure you are a very busy man and if this isn't something you have time to entertain I wholeheartedly understand.

Thank you for your time!

[Signature]

Dear Friend,

Thanks for your thoughtful question. I'm not sure I've got a one-size-fits-all process, but I'm happy to share what I've learned and what I do. I've only got time for a short reply this morning, so apologies in advance for the brevity of this note. I have some students coming by in a few minutes and I like to try to be present for those who are right in front of me as much as possible. I suppose it's sort of a spiritual practice for me, that "being present." The alternative (for me, anyway) is to spend too much of my time not being present, which usually takes the form of stress and anxiety about that which is geographically or chronologically distant. Anyway, while my students aren't here, I'm regarding this email from you as your "presence" in my office, so let's talk about writing...

...which I suppose we've already begun doing. For me, one of the most helpful things has been making sure not to regard writing as an optional exercise. (It's too easy for me to let the urgent crowd out the important.) Writing matters to me because it helps me to think and it helps me to be in conversation with others. If I don't give it at least a little of my time - on a regular basis, that is - then my ability to write begins to atrophy. Disciplines that matter - the ones that are most connected to our best loves - should be treated like respiration; they need to be regular and constant. If writing is a matter of loving your neighbor for you, then write regularly, just like you breathe regularly.

Of course, the metaphor breaks down, because we breathe involuntarily and always, whereas we only write occasionally. But it's at least a partly useful metaphor. Because I want to be ready to write, I keep a paper notebook in my pocket all the time, remembering the words from one of the Narnia stories (Prince Caspian, maybe?) Hmm. Let's see. Yes, here it is:

“Have you pen and ink, Master Doctor?”“A scholar is never without them, your Majesty,” answered Doctor Cornelius.

– C.S. Lewis, Prince Caspian, ch. 13

Yes, it was Prince Caspian. And here's one of my other tricks: I write after each book I read. With each book, I take time to jot down a few words and a few lines that really mattered to me in that book. Then, when I want quick access to those words, I've got them all in a single file on my computer, and I can search for the word "ink" or "scholar" and up comes this quote. My file of quotations from books is now 130 pages long. (Don't despair - I've been adding to it for 20 years!) It's a tremendous resource for writing, and it helps me to remember what I read and where I read it.

Two more quick things, since I've got to go:

1) My graduate school faculty told me that writing a 300-page dissertation seemed like a lot, but if I thought of it as a page a day for a year, it would seem much smaller, and much easier. They were right.

2) I find it helpful to write more than one thing at a time. I'll work on one thing for a while - maybe only a few minutes a day - and then I find my mind is tired of writing and thinking about that subject. So I will turn to another task, and I often find I have new energy. Oddly, I wrote my first book while I was also writing my dissertation. I'd write the doctoral thesis during the day, and then, at night, I'd write the book as a way of distracting my mind and relaxing. Now I find that if I'm working on only one thing I feel great stress. Will I finish it? What if I mess it up? These questions haunt me. But when I have many writing projects ongoing, I don't mind it very much if I run into a wall of writer's block on one of them. True story: I have written several books that I will likely never publish, and I have half-written hundreds of articles and books that I may never publish. But each one is still on my computer, and I often return to those half-written pieces to scavenge a few footnotes or paragraphs or choice words. The unfinished tasks aren't on the scrap heap; they're unpolished gems in my store-room just waiting to be set in a new piece of jewelry. I'm not ashamed of them even though I don't wear them in public; they're treasures even though most people will never see them.

I hope this helps. Keep at it! Writing has been a great source of food for my mind and a great nourishment to my convivial conversations as well. I hope you find it to be of similar benefit.

All good things,

Dave

P.S. Here are a few other things I've written about writing, and teaching writing, and the role of nature in teaching me how to write.

∞

The Slow, Important Work Of Poetry

At the time it seemed like chance that brought me to minor in comparative poetry in college.

Without having a master plan, over four years I wound up taking a number of poetry classes in four languages. Eventually I asked my college to consider them a new minor area of study. They agreed, and I graduated.

And then, slowly, over a quarter century, I began reading more poetry in more languages. It's always slow; I can't pick up a book of poems and read it like a novel. If the poetry is any good at all, I can read one or two poems, and then I've got to put the book down and let the words sit with me.

Often, I go back and read the same poem again, and again.

The very best poems I try to memorize, even though my memory for verse has never been good. I imagine most people would consider that a useless exercise, a waste of storage space in an already cluttered brain.

But in each season of my life I've found that it is some form of poetry that acts as salve to my soul's wounds or food that sustains its long journey forward. Homer's long story-poems; old epics and sagas from Ireland and Wales and Iceland; Vedic verses and Greek scriptures; Gregorian chants that have echoed in stone chambers for centuries; Shakespeare's or Petrarch's sonnets; the Psalms and proverbs of Hebrew priests and kings; a few words put together well by Dylan Thomas, Gary Snyder, Tomas Tranströmer, or C.S. Lewis; or the timely phrases of some of my favorite contemporaries like Patrick Hicks, Abigail Carroll, Mary Karr, Wendell Berry, Melissa Kwasny, John Lane, or Brian Turner. Each of them has, at some point, given me the daily bread I craved.

I can't seem to predict when the need will arise, but suddenly, there it is, and I find myself quoting Joachim du Bellay's sonnet about travel, and home:

That sonnet often reminds me, in turn, of verses about Abraham.

I am no good at praying, but I often wish I were. I think the fact that we make light of prayer - both by mocking those who pray and by being those who speak piously of prayer but who do not allow ourselves to confess the weakness prayer implies - says something of another shared longing, not unlike the longing for home. We long to comfort those far away when tragic events fall on them. They may be total strangers, but we know how horrible we would feel in their place, and we know that right now there is nothing we can do to staunch the flow of pain for them. But we can hold them in the center of our consciousness and, for a little while, not let any lesser thoughts crowd them out of our hearts and minds. We can, for a little while, consider our lives to be connected to theirs. We can, for a little while, ask ourselves what we might do to change the world so that this pain will not be inflicted on others.

Since I am not adept at praying, In those times I find the prayers of others buoy me up above the waves of emotional tempest. The prayer books of my tradition - the various versions of The Book of Common Prayer - often transform my anguish into something articulate. Of course, we turn to that same book when a baby is born, when a couple is wed, and when our beloved are interred. These events? We know they are coming, and yet it is not easy to prepare oneself, to be always ready for those days. I live in a tent; poetry often gives me a foundation to build on, and the better I've memorized it, the stronger that foundation becomes.

Those words, buried like seeds, slowly come to bear fruit in my life. Sometimes I wonder: was it really chance that brought me to the poems?

In the hardest of times, and also in the most joyful times, the words of poets are like a cup of water in a dry place. They refresh me, and they clear my throat so that I can take in that which sustains my own life, and speak other words, both old and new, that may sustain the lives of others.

Without having a master plan, over four years I wound up taking a number of poetry classes in four languages. Eventually I asked my college to consider them a new minor area of study. They agreed, and I graduated.

And then, slowly, over a quarter century, I began reading more poetry in more languages. It's always slow; I can't pick up a book of poems and read it like a novel. If the poetry is any good at all, I can read one or two poems, and then I've got to put the book down and let the words sit with me.

Often, I go back and read the same poem again, and again.

The very best poems I try to memorize, even though my memory for verse has never been good. I imagine most people would consider that a useless exercise, a waste of storage space in an already cluttered brain.

But in each season of my life I've found that it is some form of poetry that acts as salve to my soul's wounds or food that sustains its long journey forward. Homer's long story-poems; old epics and sagas from Ireland and Wales and Iceland; Vedic verses and Greek scriptures; Gregorian chants that have echoed in stone chambers for centuries; Shakespeare's or Petrarch's sonnets; the Psalms and proverbs of Hebrew priests and kings; a few words put together well by Dylan Thomas, Gary Snyder, Tomas Tranströmer, or C.S. Lewis; or the timely phrases of some of my favorite contemporaries like Patrick Hicks, Abigail Carroll, Mary Karr, Wendell Berry, Melissa Kwasny, John Lane, or Brian Turner. Each of them has, at some point, given me the daily bread I craved.

I can't seem to predict when the need will arise, but suddenly, there it is, and I find myself quoting Joachim du Bellay's sonnet about travel, and home:

Heureux qui, comme Ulysse, a fait un beau voyage

Ou comme cestuy-là qui conquit la toison

Et puis est retourné, plein d'usage et raison

Vivre entre ses parents le reste de son âgeHis simple words save me from forming new ones and free me to think and feel as the occasion demands; his words give utterance to what I find welling up inside me. His words change my homesickness into a stage in a worthwhile journey. Here is a very loose translation of those lines: "Happy is he who, like Ulysses, made a beautiful journey, or like that man who seized the Golden Fleece, and then traveled home again, full of wisdom, to live the rest of his life with his family." We are pulled in both directions at once: towards the Golden Fleece and adventures in Troy, and towards the home we left behind when we departed on our quest.

That sonnet often reminds me, in turn, of verses about Abraham.

Consider Abraham, who dwelled in tents,

because he was looking forward to a city with foundations.This longing for home that I sometimes have when I travel is itself no alien in any land. We all may feel it in any place. Everyone feels lost sometimes. Knowing that others have found words to express their feeling of being lost is itself a reminder that we are not alone. Hölderlin's opening words in his poem about St. John's exile on Patmos say this well:

Nah ist, und schwer zu fassen, der GottIt does seem that God - like home and family and love and neighbors - is close enough to grasp, so close that we could meaningfully touch them all right now. And yet so far that nothing but our words can draw near.

I am no good at praying, but I often wish I were. I think the fact that we make light of prayer - both by mocking those who pray and by being those who speak piously of prayer but who do not allow ourselves to confess the weakness prayer implies - says something of another shared longing, not unlike the longing for home. We long to comfort those far away when tragic events fall on them. They may be total strangers, but we know how horrible we would feel in their place, and we know that right now there is nothing we can do to staunch the flow of pain for them. But we can hold them in the center of our consciousness and, for a little while, not let any lesser thoughts crowd them out of our hearts and minds. We can, for a little while, consider our lives to be connected to theirs. We can, for a little while, ask ourselves what we might do to change the world so that this pain will not be inflicted on others.

Since I am not adept at praying, In those times I find the prayers of others buoy me up above the waves of emotional tempest. The prayer books of my tradition - the various versions of The Book of Common Prayer - often transform my anguish into something articulate. Of course, we turn to that same book when a baby is born, when a couple is wed, and when our beloved are interred. These events? We know they are coming, and yet it is not easy to prepare oneself, to be always ready for those days. I live in a tent; poetry often gives me a foundation to build on, and the better I've memorized it, the stronger that foundation becomes.

Those words, buried like seeds, slowly come to bear fruit in my life. Sometimes I wonder: was it really chance that brought me to the poems?

In the hardest of times, and also in the most joyful times, the words of poets are like a cup of water in a dry place. They refresh me, and they clear my throat so that I can take in that which sustains my own life, and speak other words, both old and new, that may sustain the lives of others.

∞

The Lesser Feast of C.S. Lewis

On this day in 1963, Clive Staples Lewis died. Some of us now observe November 22nd as the Lesser Feast of C.S. Lewis. Here is one of my favorite passages from Lewis:

“To be frank, I have no pleasure in looking forward to a meeting between humanity and any alien rational species. I observe how the white man has hitherto treated the black, and how, even among civilized men, the stronger have treated the weaker. If we encounter in the depth of space a race, however innocent and amiable, which is technologically weaker than ourselves, I do not doubt that the same revolting story will be repeated. We shall enslave, deceive, exploit or exterminate; at the very least we shall corrupt it with our vices and infect it with our diseases. We are not yet fit to visit other worlds. We have filled our own with massacre, torture, syphilis, famine, dust bowls and all that is hideous to ear or eye. Must we go on to infect new realms? ...It was in part these reflections that first moved me to make my own small contributions to science fiction. In those days writers in the genre almost automatically represented the inhabitants of other worlds as monsters and the terrestrial invaders as good….The same problem, by the way, is beginning to threaten us as regards the dolphins. I don’t think it has yet been proved that they are rational. But if they are, we have no more right to enslave them than to enslave our fellow-men. And some of us will continue to say this, but we shall be mocked.”--C.S. Lewis, “The Seeing Eye,” in Christian Reflections, Walter Hooper, Ed. (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1968), 173-4.

∞

The Trivium And The Quadrivium

The Seven Liberal Arts (and their aims)

At some point in the Middle Ages, through a slow process of growth and refinement, educators came to identify seven arts that were considered liberal. The seven liberal arts were the arts practiced by people who were, or who would be, free. (The Latin word liber can mean "a free man.")

The liberal arts were divided into two groups: the trivium and the quadrivium. As the names suggest, the trivium included three arts, and the quadrivium included four.

The trivial arts sought to teach eloquentia, or eloquence, the proper use of words. The quadrivial arts aimed at sapientia, or sapience, the proper use of numbers.

In each case there is a natural progression, beginning with the rudiments and building on those foundations to help the student master eloquence and sapience.

The Trivium and the Quadrivium (and how they are built)

The trivium proceeds like this:

The quadrivium proceeds like this:

But Is Any Of This Relevant?

It's not hard to see that a lot of this is outdated, especially in the quadrivium, which was like the STEM of the Middle Ages, focusing on mathematics, engineering, and natural sciences. We no longer believe in the "music of the spheres" or that the motion of astronomical bodies is governed by harmony akin to music. And our sciences and humanities have grown to include many other disciplines that (at least at first) don't seem to be included here.

It's also not hard to see that some of the way we educate today still has echoes of this structure. For instance, until recently, we called children's schools "grammar schools," and this is why.We still consider it important to begin important enterprises with teaching the relevant vocabulary, grammar and logic: we often begin classes by introducing new vocabulary, and we begin contracts by defining terms.

And while we don't think of outer space as being a set of nested, harmonious spheres governed by intelligences who receive their direction from the Empyrean, we do think number is extremely important as a tool for discovering how nature works. This may seem like the most obvious of points, but that is because the idea has pervaded our thinking. It's a good idea, and it stuck. Similarly, we have the hunch that inquiry into the nature of things will in fact be met with answers. Again, this seems obvious, but not every culture has thought so. The idea has stuck, and it has paid off.

Yes, But Only If You Care About Science And Freedom.

In my view, the trivial arts and their organization remain as relevant as they once were, for three reasons.

First, every free person needs to know how words are used. If you don't learn to use them, and then practice with them, you will be easily misled. If you don't study persuasion, you are far less likely to know that you are being persuaded.

Second, and related to the first point, the sciences depend upon the trivial arts. Students who cannot read and write cannot learn effectively.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, long study in the humanities leads one to consider both the way words are used for persuasion and the ethics of persuasion. People who are trained in the conclusions of the sciences are not scientists, they are databanks. People who are trained in some of the methods of the sciences are technicians. Databanks and technicians are useful to other people. But what we need are people trained in the scientific method, which, by the way, is not something we get from the sciences. It is tested and approved by the sciences, but the natural sciences do not give it to us. Which of the natural sciences could discover a scientific method, after all? Scientific method is about the proper handling of data, the examination of claims and propositions, and the distribution of relevant conclusions. Look back at the description of the trivium and the quadrivium and you'll see that this is the work of the former, not of the latter.

The Real Crisis In The Humanities

There is a lot of talk these days about the crisis in the humanities. The money is all in the sciences, and smart students should go there to study, we are told. College administrations look to humanities departments as service departments to bolster the offerings of the science departments, who do the real work of the university.

I actually don't dispute this view, even though I'm in the humanities. It's quite obvious that much of the money is in the sciences, and I think that smart students should study the sciences. That's because I think every student should study the sciences.

But I also think that smart students should engage in long study of the humanities. The sciences depend upon the humanities, just as the quadrivium was legless without the trivium. More importantly, people who want to be free -- that is, people who do not wish to be persuaded without their consent, people who wish to think for themselves, people who wish to wield tools and not just to be the tools of others -- these people need to study the humanities.

The crisis in the humanities is that even in the humanities we've allowed ourselves to forget how interrelated all the disciplines are. It's time to brush up our eloquence, for the sake of our students, and take this message to our schools.

*****

Addendum: A friend wrote to me and pointed out that I called the second part of the Trivium "logic" when I should have named it "dialectic," which includes both logic and disputation. I don't dispute his correction.

I've also since discovered Dorothy Sayers' "The Lost Tools of Learning," an illuminating essay on the medieval liberal arts. I wrote this post hastily, after a meeting at my college where the question of what an education ought to do was under consideration. I wanted to make a thumbnail sketch of the Trivium and Quadrivium for my colleagues, and this was the result of some quick typing in the last few minutes of the workday. A fuller picture would have included C.S. Lewis' essay "Imagination and Thought in the Middle Ages," and at least some mention of Martianus Capella. Maybe another time I'll return to this topic and write that fuller essay. For now, these references will have to suffice.

At some point in the Middle Ages, through a slow process of growth and refinement, educators came to identify seven arts that were considered liberal. The seven liberal arts were the arts practiced by people who were, or who would be, free. (The Latin word liber can mean "a free man.")

The liberal arts were divided into two groups: the trivium and the quadrivium. As the names suggest, the trivium included three arts, and the quadrivium included four.

The trivial arts sought to teach eloquentia, or eloquence, the proper use of words. The quadrivial arts aimed at sapientia, or sapience, the proper use of numbers.

In each case there is a natural progression, beginning with the rudiments and building on those foundations to help the student master eloquence and sapience.

The Trivium and the Quadrivium (and how they are built)

The trivium proceeds like this:

The quadrivium proceeds like this:

But Is Any Of This Relevant?

It's not hard to see that a lot of this is outdated, especially in the quadrivium, which was like the STEM of the Middle Ages, focusing on mathematics, engineering, and natural sciences. We no longer believe in the "music of the spheres" or that the motion of astronomical bodies is governed by harmony akin to music. And our sciences and humanities have grown to include many other disciplines that (at least at first) don't seem to be included here.

It's also not hard to see that some of the way we educate today still has echoes of this structure. For instance, until recently, we called children's schools "grammar schools," and this is why.We still consider it important to begin important enterprises with teaching the relevant vocabulary, grammar and logic: we often begin classes by introducing new vocabulary, and we begin contracts by defining terms.

And while we don't think of outer space as being a set of nested, harmonious spheres governed by intelligences who receive their direction from the Empyrean, we do think number is extremely important as a tool for discovering how nature works. This may seem like the most obvious of points, but that is because the idea has pervaded our thinking. It's a good idea, and it stuck. Similarly, we have the hunch that inquiry into the nature of things will in fact be met with answers. Again, this seems obvious, but not every culture has thought so. The idea has stuck, and it has paid off.

Yes, But Only If You Care About Science And Freedom.

In my view, the trivial arts and their organization remain as relevant as they once were, for three reasons.

First, every free person needs to know how words are used. If you don't learn to use them, and then practice with them, you will be easily misled. If you don't study persuasion, you are far less likely to know that you are being persuaded.

Second, and related to the first point, the sciences depend upon the trivial arts. Students who cannot read and write cannot learn effectively.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, long study in the humanities leads one to consider both the way words are used for persuasion and the ethics of persuasion. People who are trained in the conclusions of the sciences are not scientists, they are databanks. People who are trained in some of the methods of the sciences are technicians. Databanks and technicians are useful to other people. But what we need are people trained in the scientific method, which, by the way, is not something we get from the sciences. It is tested and approved by the sciences, but the natural sciences do not give it to us. Which of the natural sciences could discover a scientific method, after all? Scientific method is about the proper handling of data, the examination of claims and propositions, and the distribution of relevant conclusions. Look back at the description of the trivium and the quadrivium and you'll see that this is the work of the former, not of the latter.

The Real Crisis In The Humanities

There is a lot of talk these days about the crisis in the humanities. The money is all in the sciences, and smart students should go there to study, we are told. College administrations look to humanities departments as service departments to bolster the offerings of the science departments, who do the real work of the university.

I actually don't dispute this view, even though I'm in the humanities. It's quite obvious that much of the money is in the sciences, and I think that smart students should study the sciences. That's because I think every student should study the sciences.

But I also think that smart students should engage in long study of the humanities. The sciences depend upon the humanities, just as the quadrivium was legless without the trivium. More importantly, people who want to be free -- that is, people who do not wish to be persuaded without their consent, people who wish to think for themselves, people who wish to wield tools and not just to be the tools of others -- these people need to study the humanities.

The crisis in the humanities is that even in the humanities we've allowed ourselves to forget how interrelated all the disciplines are. It's time to brush up our eloquence, for the sake of our students, and take this message to our schools.

*****

Addendum: A friend wrote to me and pointed out that I called the second part of the Trivium "logic" when I should have named it "dialectic," which includes both logic and disputation. I don't dispute his correction.

I've also since discovered Dorothy Sayers' "The Lost Tools of Learning," an illuminating essay on the medieval liberal arts. I wrote this post hastily, after a meeting at my college where the question of what an education ought to do was under consideration. I wanted to make a thumbnail sketch of the Trivium and Quadrivium for my colleagues, and this was the result of some quick typing in the last few minutes of the workday. A fuller picture would have included C.S. Lewis' essay "Imagination and Thought in the Middle Ages," and at least some mention of Martianus Capella. Maybe another time I'll return to this topic and write that fuller essay. For now, these references will have to suffice.

∞

Wendell Berry: Past A Certain Scale, There Is No Dissent From Technological Choice

“But past a certain scale, as C.S. Lewis wrote, the person who makes a technological choice does not choose for himself alone, but for others; past a certain scale he chooses for all others. If the effects are lasting enough, he chooses for the future. He makes, then, a choice that can neither be chosen against nor unchosen. Past a certain scale, there is no dissent from technological choice.”

-- Wendell Berry, “A Promise Made In Love, Awe, And Fear,” in Moral Ground: Ethical Action For A Planet In Peril. Kathleen Dean Moore and Michael P. Nelson, eds. (San Antonio: Trinity University Press, 2010) p. 388.

∞

Theodicy and Phenomenal Curiosity

I have, right now, a terrific headache. It is a long, spidery headache whose bulging, raspy abdomen sits over my eyes and whose long forelegs reach across my head and down my spine. One leg is probing my belly and provoking nausea. It came on suddenly, dropping from the air, and it has become a constant efflorescence of discomfort. Each moment it is renewed. I try to turn my attention away, and it pulses, drawing me back. Fine, I will give it my attention and stare it down, dominate it. No, it has no steady gaze to match; every instant it is a new hostility towards being. It will not hold still, it is my Proteus, but I am no Menelaus. I cannot grapple it into submission.

I should stop writing, stop looking at the screen, but I want, as Bugbee says in the first page of The Inward Morning, to "get it down," to attend to this moment as its own revelation. I want, in a way, to put this idea to the test. I can write and think when I am feeling well, but it is hard to write in times like this.

Life is interesting. This, too, is an interesting moment, and this pain is interesting.

The urge to turn this into a rule for others is to be resisted. My pain is interesting to me because I have chosen to make it so. I have chosen to be curious while I am able. And this is not the worst headache I've had, it's just strong and annoying.

But -- and this is the important thing, I think -- I must not insist that others do the same. I must not say that "pain is God's megaphone to rouse a deaf world," I must not say that "all things work together for good," that pain is all part of a bigger plan.

I admit that all of that may be true. It may be that the suffering of others will be the darkness that makes the brightness of the divine and eternal chiaroscuro shine brighter.

But to insist that pain is good is the privilege of those who are in no pain and the blasphemy of those who have forgotten fellow-feeling. It is lacking in sympathy, and in kindness. It is, in short, lacking in love.

In one of his letters to the church in Corinth, St. Paul wrote something like this: no matter what I say, no matter how beautifully I say it, if I speak without love, I might as well not be speaking at all. (I am paraphrasing, so if you're someone who's bothered by people paraphrasing the Bible and want to see his words, here you go.)

I cannot write any more right now.

*****

It is now several days later, and the pain is gone. Which means that now, when I think of the pain, I do so through the watery filter of time, which bends and distorts the image like water bending the image of the dipped oar. I no longer behold it as I did when I was in medias res, in the midst of things. I'm glad it doesn't hurt, but I've got to remember not to make it seem easier than it was.

Years ago a surgeon cut me open "from stem to stern" (his cheerful words, not mine) and then stapled me back together. I awoke barely able to breathe. The painkillers they gave me didn't remove the pain, they only relocated it to a part of my brain that cared less, made it less the center of my attention. Even there, it constantly tried to crawl back into the center, to take over my consciousness. I'm grateful that it did not last long. My awareness of that gratitude gives me great sympathy for those who cannot make their pain end, who have no hope that soon the healing will make the pain a dull memory rather than a sharp presence goading their consciousness.

At the time, I found it a helpful strategy to attend to the pain as a curiosity, to tell myself "this is interesting," and to ask "what can I learn from this pain right now?" I couldn't sustain this for long, but I could do it again and again, with ever-renewed curiosity, and I found enormous solace and spiritual interest in it. It put me above my pain, and stripped my pain of its domineering attitude. It no longer loomed over me while I gazed down at it with wondering eyes.

But again, this is extremely difficult to sustain, and it probably takes a certain weird, philosophical warp of mind to begin with, a phenomenal curiosity cultivated and strengthened by long habit well before the pain began. It's hard to come up with something like this in the moment agony strikes.

*****

The upshot of all this, for me, is twofold: first, it is good to have discovered, in the midst of my own pain, that I may always regard my own life as interesting, no matter what happens. Second, I must always remember that this is a curious discovery I have made about myself, not a universal fact for all people.

Of course, I am writing my discovery down here because I hope that it will prove true for others. And I think its greatest application is not for the destruction of sharp physical pain but for addressing the flat white pain of boredom. When boredom drops down from above and wraps us in its gauzy, nauseating silk, this, too, can become the object of our curiosity. The very fact of our boredom may be examined, and examined profitably.

But in all our examinations, we must not be - we must never be - unkind by despising the pain of others, dismissing it and insisting that if we can dismiss it, they can too.

I should stop writing, stop looking at the screen, but I want, as Bugbee says in the first page of The Inward Morning, to "get it down," to attend to this moment as its own revelation. I want, in a way, to put this idea to the test. I can write and think when I am feeling well, but it is hard to write in times like this.

Life is interesting. This, too, is an interesting moment, and this pain is interesting.

The urge to turn this into a rule for others is to be resisted. My pain is interesting to me because I have chosen to make it so. I have chosen to be curious while I am able. And this is not the worst headache I've had, it's just strong and annoying.

But -- and this is the important thing, I think -- I must not insist that others do the same. I must not say that "pain is God's megaphone to rouse a deaf world," I must not say that "all things work together for good," that pain is all part of a bigger plan.

I admit that all of that may be true. It may be that the suffering of others will be the darkness that makes the brightness of the divine and eternal chiaroscuro shine brighter.

But to insist that pain is good is the privilege of those who are in no pain and the blasphemy of those who have forgotten fellow-feeling. It is lacking in sympathy, and in kindness. It is, in short, lacking in love.

In one of his letters to the church in Corinth, St. Paul wrote something like this: no matter what I say, no matter how beautifully I say it, if I speak without love, I might as well not be speaking at all. (I am paraphrasing, so if you're someone who's bothered by people paraphrasing the Bible and want to see his words, here you go.)

I cannot write any more right now.

*****

It is now several days later, and the pain is gone. Which means that now, when I think of the pain, I do so through the watery filter of time, which bends and distorts the image like water bending the image of the dipped oar. I no longer behold it as I did when I was in medias res, in the midst of things. I'm glad it doesn't hurt, but I've got to remember not to make it seem easier than it was.

Years ago a surgeon cut me open "from stem to stern" (his cheerful words, not mine) and then stapled me back together. I awoke barely able to breathe. The painkillers they gave me didn't remove the pain, they only relocated it to a part of my brain that cared less, made it less the center of my attention. Even there, it constantly tried to crawl back into the center, to take over my consciousness. I'm grateful that it did not last long. My awareness of that gratitude gives me great sympathy for those who cannot make their pain end, who have no hope that soon the healing will make the pain a dull memory rather than a sharp presence goading their consciousness.

At the time, I found it a helpful strategy to attend to the pain as a curiosity, to tell myself "this is interesting," and to ask "what can I learn from this pain right now?" I couldn't sustain this for long, but I could do it again and again, with ever-renewed curiosity, and I found enormous solace and spiritual interest in it. It put me above my pain, and stripped my pain of its domineering attitude. It no longer loomed over me while I gazed down at it with wondering eyes.

But again, this is extremely difficult to sustain, and it probably takes a certain weird, philosophical warp of mind to begin with, a phenomenal curiosity cultivated and strengthened by long habit well before the pain began. It's hard to come up with something like this in the moment agony strikes.

*****

The upshot of all this, for me, is twofold: first, it is good to have discovered, in the midst of my own pain, that I may always regard my own life as interesting, no matter what happens. Second, I must always remember that this is a curious discovery I have made about myself, not a universal fact for all people.

Of course, I am writing my discovery down here because I hope that it will prove true for others. And I think its greatest application is not for the destruction of sharp physical pain but for addressing the flat white pain of boredom. When boredom drops down from above and wraps us in its gauzy, nauseating silk, this, too, can become the object of our curiosity. The very fact of our boredom may be examined, and examined profitably.

But in all our examinations, we must not be - we must never be - unkind by despising the pain of others, dismissing it and insisting that if we can dismiss it, they can too.

∞

College Athletics: Cui Bono?

This Strange Marriage of Athletics and Academics

This week I've been considering the place of sports on American university and college campuses. (See here and here for the other pieces I've written on this this week.)

If you grow up here, it doesn't seem at all strange, because it's simply how things are. But a little reflection suggests that the juxtaposition of academics and athletics is a little strange.

I say it is "a little" strange because throughout the ages thoughtful people have said that the two complement each other. Plato's Republic discusses the relationship between gymnastics for the body and philosophy for the mind, for instance. Of course, Plato, famous for his irony, is never wholly straightforward, and the target he is aiming at is probably something else, but the characters in his dialogue act as though bodily exercise and mental exercise are related.

Walking, Playing, and Thinking

One of Socrates' other students, Xenophon, wrote in his Cynegetica that the best education comes through learning to hunt, and that book-learning should only come after a boy has learned the art of coursing with hounds, and practiced it in the country. And there are many others who tell us that moving our bodies and learning go together: Maria Montessori reminds us that the work of children is play. Philosophers as diverse as Aristotle, Nietzsche, C.S. Lewis, Henry Thoreau and Charles S. Peirce tell us that walking and thinking are natural companions.

So the strangeness of the marriage of learning and playing is not the hypothesis that the body and the mind work both need exercise. The strangeness is the way we pursue - or, just as often, fail to pursue - that hypothesis. We are told that movement helps us think, and that playing team sports teaches us virtue. If all that is true, then why do we not encourage all students to play sports?

The Irony: We Do Not Practice As We Preach

Speaking of irony, consider this: What we claim and what we actually do are at odds with one another. We say sports are good for everyone, then we expect coaches to eliminate all but the best athletes from their instruction. Rather than advertising our schools as places where students can get an excellent physical education we expect our coaches to travel far and wide to recruit only the best athletes, i.e. those who need the least instruction and who are most likely to win competitions. It is fairly obvious that, rather than using athletics as a means of inculcating virtue and fostering better thinking, we use athletics to gain honor through victories.

And of course, this is obvious to us. We want to win games because winning is a form of advertising. For good or ill, we accept the fact that high school students will often choose our school in order to participate in the glory of competitions won. But we continue to give the other justifications for participation in athletics, perhaps because we perceive that it would be crass to come right out and say "Come to our college and bask in the glory won by others. It will thrill you, and it might help your job prospects," or "We hope that the victories of our athletes will help us to raise money from people who won't give unless we are winning games."

I don't want to be cynical about this. As I have suggested above and said directly in my previous posts, I'm in favor of athleticism. What troubles me about it is the way that certain college sports become increasingly professionalized. Why, after all, are student athletes considering unionizing? That's something employees do, not students.

Let Everyone Learn To Play