ecology

- This short documentary about what Urban Rivers is doing with floating gardens in Chicago. They’ve made some habitat for one of the hardier species of unionid mussels native to the river. Did you know that some mature mussels can filter 20 gallons of water a day? Here in Sioux Falls I want to restore our river. Organizations like Urban Rivers can be a good inspiration for what we might do here. If this appeals to you, I suggest making a donation to Friends of the Big Sioux River. They do a lot of good work on a tiny budget.

- David Strayer’s Freshwater Mussel Ecology: A Multifactor Approach to Distribution and Abundance Strayer recognizes that ecologists often explain distribution in terms of general factors but without much quantification and precision. His book attempts to describe “a literal, quantitative prediction of the distribution and abundance of individual species.” (p. 6) Mussels are easy to overlook and often hard to find. They can be found in water that is still or fast-moving, clear or murky, shallow or deep. They might be embedded in sunken logs, deep in the benthos (the substrate at the bottom of a body of water), or wedged into the cracks of bedrock. And they might be in places where the current, or predators like alligators and snapping turtles make it perilous for biologists to seek them by diving an sticking their hands into dark places underwater! So I’m enjoying reading about other ways of modeling where they might be found.

- Suetonius' Lives of the Caesars, especially the section on Julius Caesar. Julius Caesar is remembered for many things, but if you click that link and then search for “pearl” you’ll see some of the ways mussels appealed to him. You might be thinking “Don’t pearls come from oysters?” Yes, they do. But they can also come from many other mollusks that have nacreous shells, including snails. Some freshwater mussels are called margaritiferidae, from Latin words that mean “pearl-bearing.” They are among the most threatened of the unionid freshwater mussels. The nacre inside unionid mussel shells is what many contemporary shirt buttons imitate, harking back to a century ago when we harvested mussels by the tons out of our rivers to turn them into pearly shirt buttons. Our quest for fashion did tremendous harm to the health of our rivers and left us with much dirtier water. Suetonius points out that Julius Caesar also had a taste for fancy pearls, and could guess the value of a pearl by holding it in his hand. He outlawed wearing pearls for most of Roman society, and gave a particularly large pearl to one of his mistresses. That pearl was worth six million sesterces, which is almost unimaginably expensive. Something about pearls really catches our eye, and Suetonius tells us that Julius Caesar’s invasion of Great Britain was motivated by his desire for pearls.

- Jesus told a story once about someone who was willing to sell everything he had to buy a single pearl. Those few sentences have had a broad effect on religions around the world. They also tell us something about the economy of fashion two millennia ago. Julius Caesar died a few decades before Jesus was born in a small part of the Roman Empire, so Jesus might well have been familiar with the elite Roman taste for pearls. Perhaps he had Julius Caesar in mind when he spoke of that man who sold everything. If so, that would turn Jesus' parable into a political commentary.

- Henry Bugbee, The Inward Morning. Don't try to read this book quickly, and if you're not prepared to do the hard work of thinking, move on and read something else. But if you're willing to read slowly and thoughtfully, this book can change your life. Bugbee was a philosophy professor and an angler.

- Henry David Thoreau, A Week On The Concord and Merrimack Rivers; The Maine Woods. Thoreau was an occasional angler, and an observer of anglers.

- Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac and the title essay in The River Of The Mother Of God, about unknown places. Leopold only writes a little about fish and fishing, but those occasional sentences about angling tend to be shot through with insight.

- John Muir, Nature Writings.

- John Steinbeck, Log From The Sea of Cortez. An apology for curiosity, in narrative form. One of my favorite books.

- Paul Errington, The Red Gods Call. Not brilliant writing, but a fascinating set of memoirs from a professor of biology who put himself through college as a trapper, and about how the Big Sioux River in South Dakota was his first real schoolroom. He talks a good deal about hunting and fishing and what he learned through encounters with animals.

- Kathleen Dean Moore, The Pine Island Paradox. Moore is an environmental philosopher who writes winsomely ans insightfully about what nature has meant to her family.

- Nick Lyons. Nick very kindly wrote the foreword to my book, and when I first got in touch with him about this I discovered he and I had lived only a few miles from each other in the Catskill Mountains for years. Sadly, by the time I discovered this I'd already moved away, and he was packing up to move to a new home, too. We both love the miles of small trout streams of those mountains, though. Nick has been a prolific writer and he has promoted a lot of great writing through his lifelong work as a publisher as well. Nick has a new book, Fishing Stories, just published in 2014.

- Norman Maclean, A River Runs Through It

- Ernest Hemingway, especially "Big Two-Hearted River" and the other Nick Adams stories

- James Prosek. Several books, including Trout: An Illustrated History; Early Love And Brook Trout; and Joe And Me: An Education In Fishing And Friendship

- Ted Leeson, The Habit Of Rivers

- Kurt Fausch’s new book, For The Love Of Rivers: A Scientist’s Journey. Brilliant writing by one of the world's leading trout biologists.

- Craig Nova, Brook Trout and the Writing Life. I also like his novels, and will recommend The Constant Heart.

- Christopher Camuto, who writes frequently for Trout Unlimited's journal, Trout.

- Ian Frazier, The Fish's Eye.

- Douglas Thompson, The Quest For The Golden Trout

- Izaak Walton, The Compleat Angler

- Dame Juliana Berners, The Boke Of St Albans, later editions of which contain A Treatyse of Fysshynge with an Angle, possibly authored by someone else.

- Nick Karas, Brook Trout (a nice collection of short works about brook trout, including some of my favorite stories)

- Lee Wulff

- Lefty Kreh

- John Gierach. Gierach has written a lot about angling, so it's not surprising that so many people mention him to me. Many of those mentions are positive, but some anglers mention his name with disgust. I haven't read much of his work, so I can't yet say why.

- David James Duncan, The River Why. This is a fun novel set in the Northwest, but it reminds me of the New Haven River in Vermont: there are some long dry stretches one has to plod through, but repeatedly one comes to depths that make the flatter, shallower parts worthwhile.

- Thomas McGuane, The Longest Silence.

- Bill McMillan

- Roderick Haig-Brown

- Mike Valla, The Founding Flies

- Michael Patrick O’Farrell, A Passion For Trout: The Flies And The Methods

- Peter Reilly, Lakes and Rivers of Ireland

- Derek Grzelewski, The Trout Diaries: A Year of Fly-fishing In New Zealand and The Trout Bohemia: Fly-Fishing Travels In New Zealand

- Eeva-Kaarina Aronen, Die Lachsfischerin. A novel set in Finland, about fly-fishing and fly-tying in the 18th century. The title translates as “The Salmon Fisherwoman”

- Ian Colin James, Fumbling With A Fly Rod (Scotland)

- Zane Grey, Tales of the Angler’s Eldorado: New Zealand

- Leslie Leyland Fields, Surviving the Island of Grace; and Hooked! Fields and her family are commercial fishers in Alaska, and her writing comes recommended to me from a number of sources.

- Sheridan Anderson, The Curtis Creek Manifesto

- Harry Middleton, The Earth Is Enough: Growing Up In A World Of Fly-fishing, Trout, And Old Men (Memoir)

- Paul Schullery, Royal Coachman: The Lore And Legends of Fly-fishing

- Gordon MacQuarrie

- Patrick McManus

- Vince Marinaro, The Game of Nods

- Rich Tosches, Zipping My Fly

- Robert Lee, Guiding Elliott

- Peter Heller, The Dog Stars (novel)

- Paul Quinnett, Pavlov’s Trout

- Dana S. Lamb Where The Pools Are Bright And Deep; Bright Salmon and Brown Trout

- John Shewey, Mastering The Spring Creeks

- Ernest Schweibert, Death of a Riverkeeper; A River For Christmas

- Richard Louv, Fly-fishing for Sharks: An Angler’s Journey Across America

- John Voelker’s short story “Murder”

- Dave Ames, A Good Life Wasted, Or 20 Years As A Fishing Guide

- Craig Childs, The Animal Dialogues, especially the chapter “Rainbow Trout”

- Randy Nelson, Poachers, Polluters, and Politics: A Fishery Officer’s Career

- Anders Halverson, An Entirely Synthetic Fish: How Rainbow Trout Beguiled America And Overran The World

- Thomas McGuane, A Life In Fishing

- Bob White

- Robert Ruark

- Tom Meade

- Hank Patterson

Pearls

Reading this morning about freshwater mussels (surprise!) in four contexts:

If you know me, you know this is where I live: the intersection of classics, great texts, religion, invertebrate and riparian ecology, mathematics, and clean water. I need a simpler way to describe the intersection of my interests, but for this morning I’ll leave it at this:

This morning I’m reading about pearls.

On Telling Stories

“Knowing on some intuitive level that we humans are guided by story, he ultimately called for the telling of the universe story. He felt that it was only in such a comprehensive scale that we could situate ourselves fully. His great desire was to see where we have come from and where we are going amid ecological destruction and social ferment. It was certainly an innovative idea, to announce the need for a new story that integrated the scientific understanding of evolution with its significance for humans. This is what he found so appealing in Teilhard’s seminal work."

-- Mary Evelyn Tucker, in her preface to Thomas Berry’s The Sacred Universe. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009) (emphasis is mine)

“I’m one who dwells outside the camp of literary theory—so far outside that I can’t pretend to know much of what goes on there. I know scarcely more about deconstruction or postmodernism, say, than bumblebees and hummingbirds know about engineering. I don’t mean to brag of my ignorance nor to apologize for it, but only to explain why I’m not equipped to engage in debates about literary theory. What I can do is express my own faith in storytelling as a way of seeking the truth. And I can say why I believe we’ll continue to live by stories—grand myths about the whole of things as well as humble tales about the commonplace—as long as we have breath.”

-- Scott Russell Sanders, A Conservationist Manifesto. (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2009) (emphasis is mine)

A few years ago my wife and I, along with another family at our university, established a scholarship for Native American and First Nations students who wish to study to become storytellers. (Feel free to add to it by giving here if you are so inclined.)

Some people have since asked us why we did not invest our money in something more practical like helping individual students get into business or medical school. After all, that's where the money is, and higher income can correspond to greater independence and greater influence.

We see their point, but we both have committed ourselves to what might be considered storytelling disciplines because we think that stories shape lives and communities. A free society depends on good investigative journalists, good attorneys, and good public schools. A thriving society depends as well on good art and literature. And while religion has its downsides, it also has very strong upsides, and communities draw great benefit from healthy faith communities that remind us of our values, that give us places to congregate, to engage in commentary and contemplation, to welcome new life, to sustain commitments, to help us to mourn.

We often talk about the importance of STEM disciplines and healthcare, but I think we would do well to pay a little more attention to the way that good storytelling shapes healthcare (and the way bad storytelling makes us doubt good health practices like vaccination, for instance.)

I am persuaded that stories shape communities. They take what we have received from the past and transform and transmit it. If I am right, then I am prudent to invest in good storytelling. In the case of Native American and First Nations communities, I know just enough to know that there's a lot I don't know. And I'd like to know more.

I've been working with Bio-Itzá, a small Maya Itzá environmental group in Guatemala for the last decade, and I am constantly learning from the stories of their few surviving elders who grew up hearing the Itzá language spoken. The preservation of those words and stories means not just the preservation of a few tall tales, but the preservation of everything that is encoded and deeply rooted in those stories. The stories are cultural and ecological palimpsests, and when the Itzá elders tell them, they are passing on far more than mere words.

So my wife and I are committed to helping others to tell their stories. Because "we are guided by story," and "storytelling [is] a way of seeking the truth," and "we'll continue to live by stories."

A Short Story: Mercy

When we left the Earth we thought we had escaped. We were the wealthiest people on the planet, and we had access to the best technology in history. People were willing to do whatever we wanted because we paid well.

We planned a thousand-year trip, a one-way flight to another home. We made arrangements for terraforming ships to arrive a little more than a century before we would, and we took the slow route so that the world would have time to get started before we got there. We knew it would be hard, that after a long sleep we’d wake up to colonize uninhabited territory. We knew there was real risk, but we also knew that the risk on earth was growing with the population. We wanted a new life for ourselves and for our children. We were young, and healthy, and strong.

What we did not count on was the way technology would change. We thought we were leaving a dying world, and we were. As we left the planet the trail of smoke from our burning fuel was our last goodbye, our last contribution to an increasingly unbreathable atmosphere. We meant no harm, but we had to burn some fuel to escape gravity.

Who knew that when we left, the world we left behind would undergo such changes? The population collapse that we expected took place, and we were lucky to escape before it did. That much we foresaw. But we did not think anyone would survive long after we left. When the population decreased, the air and the water started to clean themselves up, at least a little, and the people who made it through that first year of suffering came out of it stronger and more committed to never letting in happen again. They moved more slowly and more carefully than we did. They focused their energies on cleaning up the mess we left behind. And they were pretty good at it, but not good enough. Some of what they did allowed them to survive another few decades, but they saw that the damage was done and the planet was not a place they could stay for long. So they came up with a new plan, to help not just a few people but the whole surviving population of earth to head to the only known survivable exoplanet, one that had been discovered by our investments, and that was already on its way towards being terraformed. They headed for the same planet we had already claimed for our own.

And they arranged to get here first.

I’m writing this while my husband is on the radio, talking with the military patrol that was waiting for us. They say we cannot come down to the surface, and I am trying to hold back my tears. We worked so hard for this, we bought this, we sacrificed everything we had for this, and now they are refusing us entry. They knew we were coming, and they have been waiting for us.

How can they do this to us? We’re the same people, the same species! Humans are nowhere else in the universe. There is no other home for us. The place we all left is uninhabitable, but now they are telling us that we must turn away. I don’t know what this will mean. Do they want us to go back? We cannot; nothing is there waiting for us. Have they found a new place for us to go? My husband has shushed me. The military officer is saying they do not know of other planets. Why are we not allowed here? Why can we not land on the other side of the planet? I know, I’m sorry. I’ll keep it down.

We are traitors, they say. We left them in their time of need, and we left destruction in our wake. They don’t trust us, and they will not let us land. Hasn’t enough time gone by? Can’t we bury the hatchet? Why won’t they forgive us? What are we going to do?

They say they will refuel us. This is their idea of kindness. We are being given enough fuel and supplies to return to Earth. Another millennium of sleep, and perhaps the Earth we left will welcome us home, they say, but we are not welcome here.

My husband is angry. He says that when our ship is refueled he plans to crash it into their city below. They say that they will stop us. They have boarded our ship and sedated my husband. They are about to sedate me, but they are letting me write this last sentence so that when we get back to Earth we will remember their mercy.

Copyright November 10, 2018 David L. O'Hara

Teaching Tropical Ecology in Belize and Guatemala

|

| Sunrise on the Barrier Reef in Belize |

In this post I'll try to answer some of the questions that we are often asked about the course. Probably the most common question is "What do you do in your course?" The second most common must be "How can I teach a course like that?" I'll start with the first question:

What do you do in Guatemala and Belize?

The short answer to this question is a lot. I'll try to summarize.

Our approach to tropical ecology includes the standard elements you'd find in any ecology course: our students read a lot about the ecosystems and the prominent species of plants and animals they're likely to encounter. We teach them what we know about the systems we think we understand, and we tell them about the big gaps in our knowledge that we're aware of - knowing full well that we likely have blind spots we aren't aware of.

In Guatemala this means learning about the ecology of a dense forest growing on a karst plateau, and a deep lake where the water does not circulate much.

In Belize we study the mangroves and the barrier reef. The mangroves are like a porous filter between salt and fresh water, like a cell wall on a macro scale. They serve as a buffer against hurricanes; they keep topsoil from eroding into the sea, and they are a rich and colorful nursery for thousands of species.

The Importance of Human Ecology

We want our students to learn much more than the plants, animals, soil, air, and water, though. Perhaps more than anything, we want them to learn the human ecology of the places we visit. Ecology is not merely an academic study; it is, at its heart, the study of both the world and of our place in it. We don't just look at macaws, jaguars, vines, and ceiba trees; we look at the way our lives - even our visit to these amazing places - affect and are affected by these plants and animals. We don't stay in hotels; we rent rooms in local homes, and we eat meals with local people. We hire local teachers to teach us Spanish and the Itzá language. We study the history of the Itzá people, and we visit ancient ruins. We walk through the forest and camp overnight with local guides who can teach us what they know of that place. We spend time playing soccer with a local youth group, we talk with and listen to local teachers, nurses, physicians, forest rangers, ecologists, NGO volunteers, government officials, town elders, and children. If the ecology of the place matters, surely it matters because these people whose ancestors have lived there for so long matter.

|

| Tikal |

|

| The church in San José, Petén, Guatemala |

In fact, even if you think they don't matter to you, if you're reading this post in North America these people do matter to you. If their ecology suffers, they will be forced to move to look for new sources of income and food. Simple-minded and disingenuous politicians will tell you this is a problem to be solved by erecting a wall on our border, but walls are a partial solution at best, and at worst, they are blinders that keep us from seeing the source of the problem; walls ignore the real illness and conceal the symptoms, as though willful ignorance were good medicine. The real question - in my mind, anyway - is why anyone who lived on the shores of Lake Petén Itzá would ever want to leave. The answer is that people leave beautiful homes when those homes cease to be liveable. Which means the medicine that is needed is one that treats the illness itself, and not just the symptoms. My students (I hope) return from our course no longer able to see Guatemalan immigrants to the United States as a mere abstraction. Break bread in someone's home and you will see that they are human, too, with lives as particular and intricate and important and rooted as your own. Only when we disturb those roots and strip away the soil must the lives be transplanted.

This is what I mean by human ecology.

|

| One of my students examining and being examined by nature |

Where do you go?

Our time in Guatemala is chiefly in central and northern Petén. Until recently, the landscape of northern Petén was dominated by dense forest, mostly old-growth lowland forests. Surface water is mostly wetlands that vary considerably from one season to the next. There are several small-to-medium-sized rivers, and small streams, but I think a good deal of the water flows underground in karst formations; the Petén has thin soil over a wide karst plateau. There is not much water flowing on the surface. In the center of Petén there is one very deep lake, Lake Petén Itzá. This is a gem in the forest. Flying over it on a sunny day you can see the shallows fade from pale green to rich emerald, and the depths along the north side of the lake plunge to amethyst and dark sapphire. The lake has no obvious inflow or outflow, except a few small streams flowing in from the south and west, and a little creek flowing out in the east.

|

| My students leap into Lake Petén Itzá to cool off. |

In Belize we spend most of our time on one of the barrier islands that have no permanent residents. We use that island as a home base from which we can boat out to patch reefs, mangroves, turtle grass beds, deep channels, and the fore-reef. We snorkel with our students in all these places, slowly gathering experiences of similar species in diverse environments, so that the students (and we) can see both the ecology of small places and the web of relations between those small places. In mangroves, for instance, we might see juvenile caribbean reef squid that are a few inches long. When we see them on patch reefs, they might be five or six inches long, and in deep water they might reach eight inches. Each location gives us a glimpse of another stage of their life cycle.

|

| My students watch the sunset in Belize |

Why do you do this? Aren't you a Humanities professor?

Even if people don't often ask me this, it's obvious that quite a few people think it. Yes, I'm a professor of philosophy and classics, and I teach religion courses, too. But for my whole life I have been fascinated by life underwater. My most recent book was the result of eight years of researching the lives of brook trout in the Appalachian mountains, and much of my research now has to do with ocean and riparian environments in Alaska. I don't do much of what would count as research in the natural sciences, but I do spend a lot of time observing nature. This is both because I find it beautiful, and because I think it's a bad idea to try to formulate ethical principles about things I haven't experienced or seen firsthand. Of course it's not impossible to write policies about things one hasn't done; one needn't commit larceny before writing a law prohibiting theft. But experience teaches me things I might not learn in other ways, and that can keep me from trusting too much in my own opinions. As Aristotle put it,

“Lack of experience diminishes our power of taking a comprehensive view of the admitted facts. Hence those who dwell in intimate association with nature and its phenomena grow more and more able to formulate, as the foundations of their theories, principles such as to admit of a wide and coherent development: while those whom devotion to abstract discussions has rendered unobservant of the facts are too ready to dogmatize on the basis of a few observations.” Aristotle, De Generatione et corruptione, 316a5-10 (Basic Works, McKeon, trans.)I want to "dwell in intimate association of nature and its phenomena," and being able to formulate better principles is a nice side effect of doing so.

How Can I Teach A Course Like This? Can others participate in this trip?

The answer to the second of these questions is both yes and no. When I'm in Guatemala and Belize, I'm teaching. Unfortunately, this means I don't have time to bring others along and act as their tour guide.

However, the people I work with in Guatemala - the Asociación Bio-Itzá - would be happy to have you come for a visit. They're in the small town of San Josè, Petèn, Guatemala, right on the north shores of the lake. And this is the answer to the first question. Want to teach such a course? Get in touch with Bio-Itzá and they can help you set it up.

You can get to San José by flying or driving to Flores, then going around the lake by bus or car to San José, about a twenty minute drive.

|

| Flores, Petén, Guatemala |

In San José they have a traditional community medicinal garden. Just north of town is the Bio-Itzá Reserve, where you can go for guided walking tours or overnight stays. It's rustic and gorgeous. (Visits to the Reserve must be arranged in advance through Bio-Itzá.)

When you stay in San José you can easily take a launch (a wooden motor boat) across the lake to Flores, the seat of Nojpetén or Tayasal, the last Maya kingdom that fell to the Spanish.

Flores is a pretty place as well, and I like to take my students to visit ARCAS to see their animal rehabilitation center. (There's a great documentary about that place that was on PBS this year called "Jungle Animal Hospital.")

|

| Scarlet macaws being rehabilitated at ARCAS so they can be released back into the wild |

If you stay in San José, you can also take a short trip (about a half hour by car) to Tikal, or to Yaxhá, both of which are amazingly well-preserved Maya ruins. A little further past Tikal is Uaxactún, where you can see more ruins, and you can also visit a community that is trying to practice sustainable forestry.

This region is not like the tourist areas of Western Guatemala; it's more like the rural frontier of Guatemala, a long-neglected place that is now at risk of being overrun by slash-and-burn forestry, cattle farms, and oil development. It makes me think of the Dakotas over the last century; the population is small and indigenous, and most people in power in Guatemala seem to consider the forest to be a wasteland that is better burned down than preserved. I do not share that view, and while I know that more tourism will bring development and other risks to both culture and forest, the risks are already there in other forms. I hope that ecotourism will offer some counterweight to the other kinds of development that don't seek to preserve the biological integrity or cultural history of this place.

A Pretty Good Year

As my regular readers know, I'm a professor of philosophy and classics, and I teach a wide range of classes. (You can click on the "Teaching" link above to see a sampling of the courses I teach.)

Often people assume that means I wear tweed and a bowtie and that I spend my time in classrooms talking about old books. All that is true, but it's only a part of what I do.

In fact, most of my favorite classrooms are outdoors, where I'm likely to be found wearing jeans and hiking boots, a parka, or a wetsuit and snorkel.

Over the last dozen years or so my teaching and research have tended towards the environmental humanities. Think of this as the merging of the humanities side of the liberal arts with a close observation of the natural world. I consider my work to be a continuation of the work that Thales and Aristotle did when they paid close attention to animals on the ground and to the skies above, and of the work of Peirce, Thoreau, and Bugbee, all of whom let a rising trout or a solar eclipse provoke philosophical reflection.

While I don't work in an indoor laboratory, I think that education is not about the imparting of information or the filling of an empty vessel with ideas. Education is the kindling of a fire, as Plutarch wrote. And that fire is kindled by the kinds of experiences that we get in labs, art studios, shared meals, liturgies, study travel, and seminars. Lecture halls are a fine place to discuss environmental policy, to be sure. But so is a prairie, especially when you're waiting for water to boil on your camp stove, and watching the sun's beams break over the horizon and melt a light frost on your tent.

When I'm at home, I like to take my classes outside to sit under trees on campus. In the fall, I try to bring my Ancient Philosophy students camping in the Badlands of South Dakota where we can view the stars far from urban glow. Most Januaries, my students and I are in the subtropical forests of Guatemala and on a barrier island in Belize, studying ecology and culture. I rarely take a spring break, since I usually take that week to teach a course in Greece. Last summer I started teaching a class on trout and salmon in Alaska.

Those are all beautiful, memorable places, but I don't visit them as a tourist. I go to these places because I want my students to understand what is at stake when we talk about environmental regulations and practices. I want them to meet displaced people whose permafrost islands are melting or whose forests are being burned down for meager cropland. I want them to see the disappearing mangroves so that they can consider the full cost of seafood. When they stay in homes in Guatemala, my students will meet people who can never again be a mere abstraction; after we return, my students will know that the people struggling to cross borders are not nameless, faceless strangers, but people who are looking for ways to feed those they love.

A little less than a year ago I was finishing up a year that had brought me to all these places. I taught in the South Dakota Badlands, in Central America, in Greece, and in Alaska. Along the way, I had begun studying environmental law at Vermont Law School as a way of enhancing my teaching and my research. It was a good year, and as August was winding down, my desk was covered with field notebooks full of observations from Alaska and Guatemala, ready to be written up. My field notes are usually accompanied by thousands of photographs, and hundreds of sketches. I began the fall semester last year ready to teach, and ready to write.

|

| Field notes. A picture of some of the work I do when I'm inside, and not teaching; or, if you like, a picture of my desk as I recover from my injuries. I have a lot of catching up to do. |

And then I wound up in the hospital with some serious injuries. Those injuries put a sudden stop to all my teaching last fall, and for a long time I lost most of my ability to write. (I'll try to write more about the injuries and my subsequent disabilities later; it's not an easy thing to write about yet.)

Now, as this summer hastens towards the beginning of another school year, I am able to look back on last year with a sense of good fortune - albeit mixed with one very bad day and its long-term consequences. Physically, I'm regaining my flexibility and strength, a little at a time. I'm not where I was a year ago, and I may never be there again, but I'm alive and able to walk, so I'll count that in the "win" column of my life's scorecard. Intellectually, most people seem to think I'm doing fine, so I'll also count that as a win. Although it left me exhausted each day, I was able to teach again this spring, and I plan to be back in my classrooms (Deo volente!) this fall.

But here are these field notebooks, and hundreds of unedited pages on my hard drive. It was my habit to write daily. Over the last year, recovering from a brain injury has made it hard to write more than a few sentences at a time.

This morning I was looking at some of my pictures from my research in the Arctic last summer, and I was hit with a feeling of loss. Those photos and those notes should be a book by now, and perhaps several articles and book chapters, too. Instead, over the last year, as I have waited for my body and brain to heal, and as I struggled to do my teaching, I had no strength to write.

It feels funny to say that, but perhaps I am not alone in finding that a brain injury can be slow to heal and extremely tiring. I don't say that to get your sympathy. I am blessed with a very supportive community and an amazing wife who somehow has kept our life together and nursed me through my healing process. I'm fortunate. But if you've read this far, you might consider whether there are others around you who look like they're doing well physically but who might be nursing invisible wounds or who might be struggling to cope with invisible disabilities. This past year has given me a new perspective on that by making me aware of my own disabilities, most of which you won't notice if you see me at the gym or in one of my classrooms.

I might not be able to write another book yet, so for now, here's my plan: I'll write a little at a time. Thankfully, I've got my notes, sketches, and photos. I'll start with them.

If you're curious about how a professor of philosophy and classics does research and writing about nature - and how he works to recover from a serious brain injury - you might check out some of my recent publications. My book Downstream is the result of eight years of field research on the ecology of the Appalachians, with a focus on brook trout. On this blog you'll also find my recently published poem, "Sage Creek," which might give you a glimpse of my ancient philosophy class camping and stargazing in the Badlands. Or feel free to look at my photos on Instagram. Even when I can't teach in the field, I can still wander my garden with a hand lens and camera.

Gifts From My Father

The same is true for children: give them a hand lens, or an insect viewer, or a microscope with some prepared slides, and the world will suddenly become new to them. Dad planted that seed in me long ago. Now I carry a hand lens with me almost everywhere I go. I suppose the whole of my career is a reflection of the things that delight Dad and provoke his curiosity; most of them delight me and make me curious, too. And just as Dad passed on his curiosity to me, now it is my turn to pass it on to others.

Recommended Reading: Fly-Fishing and Trout

|

The focus of the course will be the char species of Alaska. These species, all members of the genus salvelinus, are commonly thought of as trout. Brook trout and lake trout are both char, as are Dolly Vardens and arctic char.

These are beautiful fish. I think many anglers love them simply because they are so beautiful to look at. When I pull one from the water I am immediately torn between wanting to hold this precious thing closely and the urge to release it immediately, before my coarse hands pollute its loveliness. The name "char" might come from Celtic roots, like the Gaelic cear, meaning "blood." They are more multi-hued than rainbow trout. The red on their sides and fins catches the eye and holds the gaze.

Over the years I spent researching and writing my own book on brook trout, I did a lot of reading. Some books call me back again and again, like Henry Bugbee's The Inward Morning and Steinbeck's Log From The Sea of Cortez. Neither one is chiefly about fly-fishing or about trout, but they're both written in a way that makes me re-think how I view the world. And they do both talk a good deal about fish, and fishing.

|

| Mayfly on my reel. Summer 2014, Maine. |

If the point of writing books about fish is to give techniques, or data, then we don't need many at all. But stories about fish and fishing are rarely about the taking of fish. More often they are about the states of mind that open up as we prepare to enter the water, or as we stand there in the river. Fishing is to such states of consciousness what kneeling is to prayer; the posture is perhaps not essential, but it is a bodily gesture that does something to prepare us to be open to a certain kind of experience. I won't belabor this point. Read my book if you really want me to go on about fishing and philosophy. For now, let me present some of my recommendations, plus the recommendations I've received:

On Nature

I teach environmental philosophy and ecology, so I begin with some orienting books.

Some Favorites

Classics

These have been recommended time and again. I'm not sure many people ever actually read the first two, though they become prized volumes in the libraries of anglers around the world.

Most Recommended

Fly-Tying

Places

One reason why there is so much writing about fishing is that fishers tend to be students of particular places. Yes, some people fish by indiscriminately approaching water and drowning hooked worms therein, but experience tends to cure most young anglers of that method. Fishing puts us into contact with what we cannot see (or cannot see well) under the water; experienced anglers learn to read the signs above the water and the place itself. We return to the same place as we return to beloved passages in books or to favorite songs, to know them better through repetition.

Other Frequent Recommendations

If I talk to a group of anglers about books for long enough, one or more of these will eventually be mentioned. Stylistically and in terms of content, they're quite different, but they all seem to speak to important moods and thoughts of anglers.

Other Recommendations

Most of these I don't know at all, so I'm not recommending them, just mentioning them. Of course, if you have more recommendations (or corrections), please feel free to add them to the comments section, below.

I'll conclude with a few other recommendations. First, when I've asked for recommendations about texts, a handful of people tell me "Tenkara." This isn't a text, but a kind of rod, and a method of fly-fishing. And yet people continue to say that word to me when I ask for texts. Why is that? I have a few guesses: there isn't a lot written about tenkara, but people who practice it have come to love its simplicity and grace. I'm not a tenkara fisher (yet) but I'm eager to learn. I have a feeling that tenkara, like so many spiritual practices or like some martial arts, is something that makes people feel they way great writing makes us feel: in it we transcend the immediacy of our environment.

Along those lines, one commenter on Facebook said this to me about my students: "Give them [a] fly rod and a stream and let them write [their] own story." There is wisdom here. It is one thing to read about waters, and quite another to enter the waters on one's own feet. Even so, I think it's important and wise to learn from those who've gone before us, too.

If you're interested in seeing some of my other book recommendations, have a look at this, this, and this.

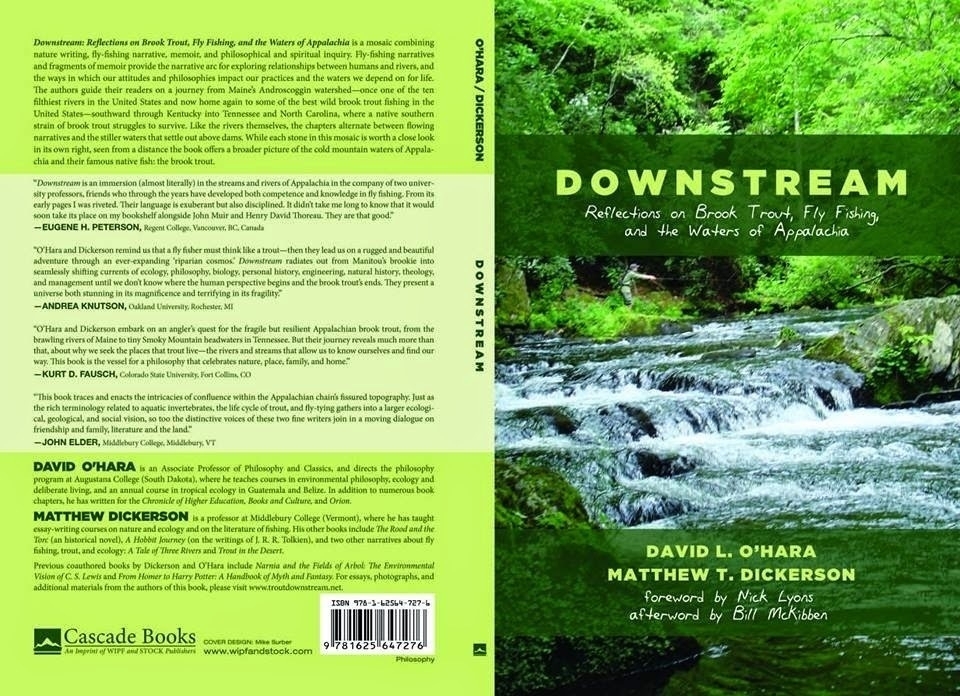

Downstream: My New Book On Brook Trout and Appalachian Ecology

It is now listed on Amazon as well, though not yet in stock there.

I'm very grateful for the foreword by Nick Lyons, the afterword by Bill McKibben, and the kind words offered by such a wide range of brilliant scholars of theology, literature, and science, like Eugene Peterson, Andrea Knutson, Kurt Fausch, and John Elder.

My Backyard Ark

Augustine once said that a key to his conversion was when he met St Ambrose. Augustine had regarded the Bible as full of flawed and problematic texts. As Augustine put it, "by taking them literally, I had found them to kill."(1) Ambrose taught Augustine that the texts of the Bible may have more than one sense. The scriptures might speak to him in more than one way. When he heard this, and heard it from a man who thought it important to study science and the liberal arts, Augustine found his spiritual home in Christianity.

Augustine once said that a key to his conversion was when he met St Ambrose. Augustine had regarded the Bible as full of flawed and problematic texts. As Augustine put it, "by taking them literally, I had found them to kill."(1) Ambrose taught Augustine that the texts of the Bible may have more than one sense. The scriptures might speak to him in more than one way. When he heard this, and heard it from a man who thought it important to study science and the liberal arts, Augustine found his spiritual home in Christianity.In recent years authors like Norman Wirzba, Bill McKibben, and Scott Russell Sanders have written about the relevance of Biblical texts for thinking about ecology. To me, they have been a little like St Ambrose. I've found one passage in Sanders to be quite helpful personally as I think about the management of my little suburban fifth-acre plot.

In his A Conservationist Manifesto, Sanders writes about the story of Noah and the Ark. He remembers that Noah was given the task of saving not just himself but every other species as well. And once they were on the ark, it was his job to care for the animals and to keep them alive. Sanders talks about books, and communities, and practices that can be like small arks in our time. One such "ark" may be the little plots of land we maintain around our homes:

"Every unsprayed garden and unkempt yard, every meadow, marsh, and woods may become a reservoir for biological possibilities, keeping alive creatures who bear in their genes millions of years; worth of evolutionary discoveries. Every such refuge may also become a reservoir for spiritual possibilities, keeping alive our connection with the land, reminding us of our origins in the green world."(2)Lately I've been surveying my yard more closely, looking to see whom I'm sharing it with, and how. I've been trying to do some phenology, like Thoreau did. I also wander my garden with lenses: a hand lens for close inspection; my phone camera and my SLR for keeping records of what lives and grows there; and I've recently set up an infrared game camera to see who passes through at night. For the curious, I've posted some photos below of what I've seen there.

*****

(1) Augustine, Confessions. Henry Chadwick's translation. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998) p. 88.

(2) Scott Russell Sanders, A Conservationist Manifesto. (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2009) p. 16.

*****

All of these images were taken by David O'Hara in the fall of 2013. You may use them elsewhere but please mention where you found them and give credit where it is due. Thanks.

Hunting, Fishing, and Climate Change

|

| Trout angling in the Black Hills of South Dakota |

This article in Outside makes just this case, with the additional point that we who seek our food in the wild are the people who ought to be advocating for real conservation: not just changes to game laws, but changes in the way we live in relationship to our world.

The Moral Issue Of Land

"[The prince] is to give his sons their inheritance out of his own property so that none of my people will be separated from his property." (Ezekiel 46.18)

|

| Central Oregon |

And this, written by Alan Paton. His younger Jarvis (in Cry, the Beloved Country) also writes prophetically about South Africa. What he says could have been written about any number of places, though:

"It is true that we hoped to preserve the tribal system by a policy of segregation. That was permissible. But we never did it thoroughly or honestly. We set aside one-tenth of the land for four-fifths of the people. Thus we made it inevitable, and some say we did it knowingly, that labour would come to the towns. We are caught in the toils of our own selfishness....No one wishes to make its solution seem easy....But whether we be fearful or no, we shall never, because we are a Christian people, evade the moral issues."As a child I thought prophets were people who predicted the future, or who spoke things God wanted to say, like spokespeople. As I've grown older, my notion of prophets has expanded to mean those people who disrupt our quotidian secular and economic concerns in order to remind us that love and justice may and must constrain our actions. What could be more important than that?

|

| Zena Reservoir and Overlook Mountain |

The question I am pondering this morning: What do love and justice require of us when it comes to land ownership?

This question is made more poignant as our state legislature is considering eliminating perpetual conservation land easements. One argument against them is that it seems unreasonable to put limitations on future people. We may rightly ask: can we consider those people who do not yet exist - and who therefore may never exist - as factors or agents in our moral reasoning?

|

| Dakota prairie |

And yet every time we consume a non-renewable resource we are making an irrevocable decision about what the land will yield for perpetuity. Land easements may be one way to offset the effects of our other decisions, and they are at least reversible if the future proves them foolish.

Jarvis correctly diagnoses us: when we think about the future, frequently we are moved by fear. Isn't that why the prince Ezekiel spoke of was tempted not to give up his land?

I also find that when I think about the future, I am also motivated by love, and that love is perhaps my strongest, my most angelic impulse. I save, teach, build, conserve, and create for my children, and for others like them. I may not be able to give them a better world, but I do feel - I admit it is, at its base, a feeling - that I owe them at least as good a world as I received.

|

| Twin Falls, Idaho |

Learn Spanish in Guatemala, Help Save the Rainforest

Immersive Spanish language learning in Guatemala’s Asociación Bio-Itzá supports cultural preservation and sustainable community development efforts.

Socrates and the Trees

I disagree with what Socrates says here, and it is an unfortunate fact of history that many Platonists have taken a similar position to this one. I just read this line in an otherwise very good book, David Keller and Frank Golley's The Philosophy of Ecology: From Science To Synthesis.

It's a fine collection of key articles in environmental philosophy. In the introduction, however, they contrast Socrates with Thoreau - something Thoreau himself did - and make Thoreau out to be the one more interested in trees. Thoreau was interested in trees, especially at the end of his life, but that does not make the comparison apt.

The irony of this line is that it comes from a dialogue in which Socrates continues to point out to his interlocutor just how much one can learn from a close observation of nature. He repeatedly draws attention to the trees, the water, and the cicadas. Socrates and Plato are not known as fathers of empiricism, but the view that their heads are so far in the Clouds that they cannot see the well they're about to step into has occupied too much of our attention. We would do better to notice that Socrates pays attention to the trees. We would do better still to pay some attention to the trees ourselves.

Two kinds of ducks

Recently I was speaking with some students about environmental philosophy, and about the ethical dimensions of hunting and fishing. Most of those students were not hunters, but all of them seemed to care about the environment. I asked them at one point if they knew how many species of ducks live in our region. I think the best (and most entertaining) answer I got was “Two: mallards and non-mallards.”

What struck me was how little, in general, my conservation-minded students know about the wildlife around them. And I think they are not unique in this. In fact, they may know a good deal more about nature than most of their generation.

Recently, Smithsonian published an article about conservation ecologist Patricia Zaradic. Zaradic worries that we are becoming ever more attached to video screens, and that, as a result, our knowledge of the natural world is suffering.

My fear is that we are, in a way, becoming modern-day Gnostics. (Gnostics hope to liberate the spirit from materiality by means of esoteric knowledge.)

But this is dangerous. Rejecting materiality–rejecting the body, its world, and its boundaries–seems like a bad idea. Maybe I’m wrong, and the transhumanists like Ray Kurzweil and his disciples have it right. But the body, it seems to me, is just as ethically significant as the soul or mind.

Losing touch with the material world makes it harder for us to notice when ecosystems are suffering. It also might make it easier for us to undervalue the bodily suffering of other people. And, speaking for myself, at least, I know that the pleasures of video screens are almost always more alluring than taking care of my own body. In fact, I’d be exercising right now–or duck hunting–but it has been a while since I checked in with my Facebook friends. I wonder if any of them can help me learn about ducks.