education

- They want to know why I continue to be a member of a church in an age when fewer and fewer people find themselves connected to traditional houses of worship or faith communities. (I have written about this in a few places, but you might like what I have written about prayer.)

- They wonder why I am still a professor in a small liberal arts college at a time when students seem disengaged, and when colleges are threatened by political headwinds, rising costs, apparent diminishing returns, and by our own decisions that weaken public opinion against us. (You can see a bit more of what I’ve written about the liberal arts here and here.

- And they wonder why I continue to work towards environmental sustainability in a place that doesn’t seem to value the environment, and where sustainability is viewed as a harmless hobby at best and a threat to business and freedom at worst. (My work focuses on the environmental humanities, and I’ve done a good deal of work in sustainability with my university, with my city, with our local zoo and aquarium, and internationally with organizations like IBM. You might also like this article I wrote about insects on Medium, but be forewarned that it is paywalled.)

- When it comes to faith, I often find others' stories more interesting than my own, and I’m glad to meet others who are seeking the way ahead with humble curiosity even if we use different words to talk about what we’re seeking and what we’re finding. So my calling is not to a building, or to a religion; rather, it feels like a consistent calling to love God and to love my neighbor as myself.

- When it comes to teaching, I have taught every age from pre-schoolers to older graduate students. I love it all. For now, I’m a tenured professor at the highest rank available to me. It took a lot of work to get here, and positions like mine are the envy of graduate students everywhere. I wouldn’t be surprised to see more and more schools eliminate tenure and reduce jobs like mine to some version of the gig economy (these things are already happening steadily around the world.) So if I were to leave this job, I’d be leaving something I probably would never find again. But I don’t feel the calling to comfortable tenure so strongly as I do feel the calling to meaningful teaching that helps others to flourish. So my calling seems always to tug me beyond my faculty office and my assigned classrooms.

- And when it comes to environmental sustainability, I often find myself scratching my head. Why wouldn’t we want to be not just good neighbors but also good ancestors? Why wouldn’t we want to pursue solutions that help people and the planet to thrive while also making sure we all flourish economically? I get it: so many of the solutions offered by environmentally-minded people threaten to cost us more in taxes, or they threaten particular practices or certain sectors of the economy. If someone came for my job or my hard-earned savings, I’d bristle as well. But it doesn’t have to be that way. We can make good use of the water we have AND we can make sure those who live downstream have clean water too. We can make good use of our soil without depleting it, and we can do it in a way that boosts profits. Etc. Here my callings all seem to come together: I feel called to help my neighbors — all of my neighbors — flourish, and to love them as myself. And to include as neighbors everything that lives, and everyone who might inherit this earth from me. I’d like my great-great-grandchildren whom I will likely never meet to look back on my life with gratitude.

- Grammar. This is the study of words, and especially:

- how definitions work, so that we can "come to terms" with one another; and

- how words are assembled into meaningful sentences or propositions.

- Logic. This is the study of the structure of arguments:

- how to assemble propositions into arguments; and

- how to draw proper conclusions from those propositions without error.

- Rhetoric. This is the study of the proper use of arguments:

- how to use arguments to persuade others; and

- how and when to persuade without misleading people.

- Arithmetic. This is the study of number.

- Geometry. This is the study of number in space.

- Music. This is the study of number in time.

- Astronomy. This is the study of number in space and time.

Why Are You Still Here?

Should you be here? (I like roads like this one.)

Like my previous post, this one begins with a question others ask me fairly often:

“Why are you still here?”

Thankfully, when I hear this question people generally aren’t asking me to leave. Rather, they’re asking why I stay. And they’re usually asking about one of three things:

I have answers for each of these, and they’re all important. My faith matters to me. So does my community, and so does the environment my community inhabits. I want my neighbors to thrive, and that means I want them to live in a place that fosters health for the whole person: physical, emotional, mental, spiritual, and economic. And my idea of “neighbor” is fairly expansive, and it includes all those whose lives are connected to my own, including the lives of other species. Jesus once pointed out that not even a sparrow can fall to the ground without God noticing it. If the sparrows matter to God, then I’d like them to matter to me.

In other words, for me, these three questions people ask me are all related to one another.

I think they’re all also related to my vocation, and to my sense of calling. In some way I feel called to and by God; I feel like teaching is my vocation; and I feel called to be a good steward of all Creation.

Those “callings” are different, but they all also feel like “deep calling unto deep.” I can’t explain them, and I don’t mean to say they’re others' callings as well. But they’re part of who I am, as far as I can tell.

One thing all those callings have in common is that they all seem to be growing:

So my best answer to this question “Why are you still here?” is this: for now, I feel called to be here.

Of course, like I said, my callings all seem to grow.

It may be that soon I’ll find a better way to answer this triple calling I feel, and if so, I hope I won’t hesitate to leave tenure and comfort and my favorite ideas when I find better ones.

Because I believe we are all in this life together, and, as some of my favorite authors have said, “all flourishing is mutual.”

So, how’s the sabbatical going?

This is the third time in my life that I have taken a sabbatical. On average, I’ve taken one about every eleven years. My first sabbatical was from a position as a campus minister, and I used it to begin graduate school. There was no obligation for me to return to that position afterwards, and I wound up not returning. Instead, I continued with grad school and eventually became a professor. My second sabbatical, which I’ve written about here, was after I first earned promotion and tenure. This current one might be my last.

Sabbaticals are a great idea. I wish everyone could have sabbaticals. Some countries have long service leave, allowing those who stick with a job for a given number of years to take some time of rest and renewal. Etymologically, “sabbatical” is supposed to be a time of rest. In most cases today, I’m not sure it still means that. Some companies offer leave for study and upskilling, which is great, but it’s usually about coming back to work as a more efficient worker. Sabbaticals seem to be more and more about efficiency. The committee that reviewed my sabbatical request sent me a letter letting me know that my sabbatical was approved, and that they expected me to write and publish the things I said I’d like to work on. If memory serves, there was nothing in there like “remember, this is mostly about rest and restoration, so don’t neglect that.”

And I find that my first impulse on sabbatical has been to use time away from the office and the classroom to catch up on all the things that get neglected when I’m working hard at being a teacher. Inbox zero is a tempting goal, even if the only way to achieve it is to mass delete emails. In other words, I am tempted to use time away from the office to catch up on things that I should have done at the office if I weren’t so damn busy.

We impose work on ourselves. Productivity is the watchword. Our discipline has monastic roots. We still wear the robes and still have our cells (offices), but the daily office of readings, the hours of resting and praying are a thing of the past. We dress like monks but we still punch the clock like everyone else. It feels like we’ve lost something big, and we’ve told ourselves the loss was freedom from outdated antiquity. I’m not sure that’s true.

A few years ago I took my students to visit a monastery in Greece. The sisters there told my students about their lives, and about their daily work and prayer. They wake up in the middle of the night and gather in their little chapel to pray, then return to bed for more sleep. When they wake up, they pray together again, and then throughout the day they return to the chapel to pray and read and sing. In between that, they do the things that make their life together possible: they grow food, harvest it, store it, prepare meals, and eat them together. Clothes get washed, floors get swept, and the work of caring for the needy in their community goes on at a steady pace. Not with breakneck urgency, but at a pace that can be maintained—that has been maintained—for centuries.

When my students heard all this, one of them asked with a look of exhaustion, “When do you take a break?” The sister looked at her with some confusion, and replied “Take a break from what? Our lives are lives of leisure.”

For most of us, including teachers at most of our nation’s small colleges, our lives are not so much lives of leisure but of busy-ness and constant work. One of the appeals of teaching used to be the possibility of leisurely conversations with students and colleagues. We spoke in lofty terms of “the life of the mind,” and of a “great conversation” that included both the living and the dead who left their words for us to contemplate. The trade-off was we teachers would accept low pay in exchange for a long tenure that included time to reflect so that we could both model good practices and teach “sound learning, new discovery, and the pursuit of wisdom.” (That line is from theBook of Common Prayer.)

The last decade feels like it has been a decade of increasing urgency at the expense of contemplation, greater push for efficiency at the expense of conversation, the replacement of teaching with instruction, the rise of software to “manage” courses for teachers (and to do homework for students), the gathering of data that will satisfy the professional accreditors.

I have more to say about this, but I’m going to stop here for now because I’m going to go do something else. Or rather, I’m going to take a little while to do very little, intentionally. One of my practices during my sabbatical has been to pay close attention to what is right before me. I do this by sketching and by writing, not with the intention of publishing my essays or of becoming a great artist, but rather in order to be more attentive. I think that’s a good model for my students, and hopefully it helps me to rest and to return as a more attentive and more caring teacher. Because teaching is not (for me, at least) about handing over information but about fostering lives of contemplation, conversation, and commentary.

John T. Meyer Interviews Me On His Leadmore Podcast

John T. Meyer, CEO of Lemonly, is one of the best interviewers I've known. In his Leadmore podcast he has interviewed immigration lawyer Taneeza Islam, Governor Dennis Daugaard, Augustana University President Stephanie Herseth Sandlin, Vaney Hariri, epidemiologist Dr. Lon Kightlinger, and a number of other leaders.

I'm delighted to have joined him in this conversation about teaching as a kind of leadership; ancestral languages; and the value of learning what some might call "unnecessary" knowledge like the liberal arts.

You can find it wherever you get podcasts. You can also find it as a video here.

Gracias, señora Orza

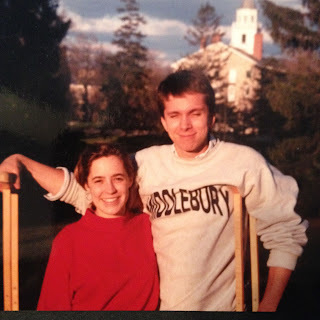

One day when I was in middle school in New York you said to me “You’re good at languages. You should go to Middlebury.” I hadn’t heard of it before, and I had been planning to attend the cheapest local college I could attend, to save my family the cost of college. Then you handed me a brochure from Middlebury, about their summer language programs. A year later, when I was leaving to work in Nepal for the summer, you gave me a blank journal as a parting gift, reminding me that writing matters.

I haven’t seen you since then, and I haven’t been able to track you down to thank you in person, so I’m firing this out into the internet to say thank you to you and to all the other teachers like you. Why? Because you changed my life.

Three years after I last saw you, I drove to Middlebury to check it out, and I fell in love with the place. I sat in on a Religion class (a subject I thought I wouldn't find interesting at all) and learned more about religion in that single hour than I thought possible.

So I applied, and I got in, with a scholarship. I guess they thought I should go there, too! Over the next four years that college made it possible for me to study in Spain; to learn to read and translate multiple forms of classical Greek; to be exposed to history as more than names and dates; to study physics, and math, philosophy, and even a little more religion.

Looking back on those years now, I see that my whole career has arisen out of classes I took there.

And best of all, I met this amazing woman! I think you’d like her. Like you, she’s smart and sweet. Like you, she encourages me to keep learning. And like you, she’s fluent in Spanish.

|

| We started dating in college, and we're still dating each other now, even though we're both married. I think you'd like her. |

Far more than the classes, she has changed my life. So often it's the people you meet--and not just the things you learn--that change you. I'm grateful to have met you both.

So thanks for being a Spanish teacher in a middle school in rural New York. Thanks for putting up with all of us kids in your classes, year after year. And thanks for taking my future seriously enough that you thought that my life, my travels, and my studies really mattered. You saw all that far more clearly than I did back then, but over the years I’ve come to see what you saw, and I’m forever grateful.

Your loving student,

Dave

On Living Imitably

Yesterday, knowing that I'd have this conversation today, I was in a reflective mood, perhaps more than usual. I was paying more attention to my daily life, I think. In the morning I taught a class on medieval philosophy. I spent some time moving stones in a garden on campus, part of a long-term project of making a meditative space for my community. I went to chapel. I met with a prospective student and her mother. Of course, I answered a lot of emails.

But one of the biggest things I did yesterday was I sat in my office with students and made them tea. And we talked about their studies and their lives.

|

| Mugs in my office, waiting to be filled. |

Tea is so simple: dead leaves and hot water. But the right mixture of leaves and water--and the right company--bring warmth to the hands and to the body; they deliver flavor and scent to the mouth and nose; they satisfy the gut in a remarkable way; they give a little stimulation of caffeine.

Perhaps most importantly, the tea, taken with another person, creates a moment. The moment lasts as long as the tea lasts, and then it moves on.

In those moments yesterday I talked with more students than I can quickly recount. (I have a lot of dirty mugs to wash when I get to the office today!) What they all wanted to talk about: how to live well.

One wanted to talk about her spiritual journey and her education, and how they meet and complement one another. Actually, quite a few wanted to talk about that.

Several wanted to talk about how to change the entire world, and to make it better for those who follow. That is, they had ideas about living sustainably, ideas that might be worth imitating, ideas that could grow and scale up.

There are times when I wish I had less paperwork to do, fewer reports to write, fewer exams to grade. (I'm falling behind in all of that, I admit.) And there are times when I wish I could seize the academy and just change it dramatically, because change in the academic world happens at a glacial pace. (And these days, the pace of glaciers is not hope-giving.) And of course there are times when I wish I had more money to give away, and that somehow the money I was paid corresponded to the amount of work I do. (Don't we all?) (Note to students: a Ph.D. in the Humanities is not a get-rich-quick scheme. FYI.)

Every year I think about leaving academics and starting up a business. When I am working for myself (yes, I've done so a number of times) I am also pretty happy. I like working with my hands, moving stones, writing books, guiding others through wild places. I like finding value where others don't see it, and then sharing that value broadly.

Today is not the day I will leave the academy, I think. Those conversations yesterday left me with the sense that while I could make a lot more money elsewhere, I am happy with the fact that I am making a difference right where I am. Maybe today's conversation will change that. In fact, I hope it will change me, at least a little. Good conversations should do that, just as pausing to look at the compass should change or at least verify the direction we are taking. After all, as I remind myself often: students are watching my trail, and some are following along behind me. The decisions I make matter for more than just my own life.

I hope today gives you a moment to pause, perhaps with a friend and a mug of something that warms you both, and with a compass that will help you to determine whether the path you are taking is worth continuing on, and imitating.

Perennial Thinking in Education, Ag, and Culture - Lori Walsh interviews Bill Vitek and me on SDPB

One of the persistent themes of his work is the connection between culture and agriculture: the two shape one another.

|

| A bit of prairie, with perennial grasses. |

Another theme that is related to the first: we all eat, and we all think, and eating and thinking indluence one another.

A third theme: we tend to focus our thinking on the annual or the short-term, neglecting the perennial and long-term. having spent a few days with Bill, I'm now reflecting on what I find one of the most provocative parts of his work: what would it mean to shift from thinking of education as an annual crop to thinking of it as a perennial? Currently we begin planting at the beginning of the season, and we expect to harvest grades and graduates at the end of the term.

What if we thought of education in the way we think about caring for perennials? What if we considered school to be more like the planting of trees than like the planting of corn? Or what if we figured out a way (as they are doing at the Land Institute, where Bill is a collaborator with Wes Jackson - here's a link to one of their co-edited books) to give our annual crops perennial roots?

|

| A view of the Augustana University campus, with historic buildings. |

I have a lot of work and thinking and cultivating ahead of me, so I won't answer those questions here. If you have taken my classes, you already know how I have been working on this over the years (think of how I speak about grades and exams in my classes, for instance). And if you've read my books (like my book on C.S. Lewis' environmental thought, or my book on brook trout as indicators of both natural ecology and cultural ecology), you know I'm working on these ideas, and they will require long cultivation. I'm okay with that.

For now, feel free to listen to Bill and me as we are interviewed by Lori Walsh on South Dakota Public Radio.

On Telling Stories

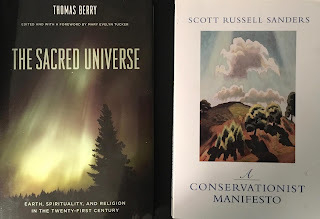

“Knowing on some intuitive level that we humans are guided by story, he ultimately called for the telling of the universe story. He felt that it was only in such a comprehensive scale that we could situate ourselves fully. His great desire was to see where we have come from and where we are going amid ecological destruction and social ferment. It was certainly an innovative idea, to announce the need for a new story that integrated the scientific understanding of evolution with its significance for humans. This is what he found so appealing in Teilhard’s seminal work."

-- Mary Evelyn Tucker, in her preface to Thomas Berry’s The Sacred Universe. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009) (emphasis is mine)

“I’m one who dwells outside the camp of literary theory—so far outside that I can’t pretend to know much of what goes on there. I know scarcely more about deconstruction or postmodernism, say, than bumblebees and hummingbirds know about engineering. I don’t mean to brag of my ignorance nor to apologize for it, but only to explain why I’m not equipped to engage in debates about literary theory. What I can do is express my own faith in storytelling as a way of seeking the truth. And I can say why I believe we’ll continue to live by stories—grand myths about the whole of things as well as humble tales about the commonplace—as long as we have breath.”

-- Scott Russell Sanders, A Conservationist Manifesto. (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2009) (emphasis is mine)

A few years ago my wife and I, along with another family at our university, established a scholarship for Native American and First Nations students who wish to study to become storytellers. (Feel free to add to it by giving here if you are so inclined.)

Some people have since asked us why we did not invest our money in something more practical like helping individual students get into business or medical school. After all, that's where the money is, and higher income can correspond to greater independence and greater influence.

We see their point, but we both have committed ourselves to what might be considered storytelling disciplines because we think that stories shape lives and communities. A free society depends on good investigative journalists, good attorneys, and good public schools. A thriving society depends as well on good art and literature. And while religion has its downsides, it also has very strong upsides, and communities draw great benefit from healthy faith communities that remind us of our values, that give us places to congregate, to engage in commentary and contemplation, to welcome new life, to sustain commitments, to help us to mourn.

We often talk about the importance of STEM disciplines and healthcare, but I think we would do well to pay a little more attention to the way that good storytelling shapes healthcare (and the way bad storytelling makes us doubt good health practices like vaccination, for instance.)

I am persuaded that stories shape communities. They take what we have received from the past and transform and transmit it. If I am right, then I am prudent to invest in good storytelling. In the case of Native American and First Nations communities, I know just enough to know that there's a lot I don't know. And I'd like to know more.

I've been working with Bio-Itzá, a small Maya Itzá environmental group in Guatemala for the last decade, and I am constantly learning from the stories of their few surviving elders who grew up hearing the Itzá language spoken. The preservation of those words and stories means not just the preservation of a few tall tales, but the preservation of everything that is encoded and deeply rooted in those stories. The stories are cultural and ecological palimpsests, and when the Itzá elders tell them, they are passing on far more than mere words.

So my wife and I are committed to helping others to tell their stories. Because "we are guided by story," and "storytelling [is] a way of seeking the truth," and "we'll continue to live by stories."

SPUnK: The Society for the Preservation of Unnecessary Knowledge

James is a Philosophy and Classics major at Augustana University, and he's also the Prime Minister of SPUnK, a campus group I advise at Augustana University.

SPUnK - the Society for the Preservation of Unnecessary Knowledge - is devoted to learning about things we don't need to learn about, because we think unnecessary knowledge is worth preserving and promoting. We distinguish between those things students are told they must study in order to get a job, and those things that we study because there is delight in wonder, and in learning new things, even if we don't yet see their practical use. As both Plato's Socrates and Aristotle pointed out, the love of wisdom begins in wonder, and we seek knowledge not for some simple or material gain but for the satisfaction of wonder and out of a desire to know. Here's Aristotle:

"Now he who wonders and is perplexed feels that he is ignorant (thus the myth-lover is in a sense a philosopher, since myths are composed of wonders); therefore if it was to escape ignorance that men studied philosophy, it is obvious that they pursued science for the sake of knowledge, and not for any practical utility.The actual course of events bears witness to this; for speculation of this kind began with a view to recreation and pastime, at a time when practically all the necessities of life were already supplied. Clearly then it is for no extrinsic advantage that we seek this knowledge; for just as we call a man independent who exists for himself and not for another, so we call this the only independent science, since it alone exists for itself."*Or, as Charles Peirce once put it, science is the practice of those who desire to find things out.**

This is what SPUnK is all about.

James and Hugh will teach you about paper towns, curiosity, education, Abraham Flexner, Albert Einstein, Rubik's Cubes, and other unnecessary knowledge. It's a short interview, well worth a few minutes of your time. Unnecessary knowledge is worth quite a lot more than a little of our time, after all.

* For two places Plato and Aristotle say this, see Plato's Theaetetus 155b and Aristotle's Metaphysics 982b.)

** Peirce writes about this in the first chapter of Justus Buchler's The Philosophical Writings of Peirce.

Good Education Should Lead To Good Questions

[....]

"If the aim of education is to gain money and power, where can we turn for help in knowing what to do with that money and power? Only a disordered mind thinks that these are ends in themselves. Socrates offers us the cautionary tale of the athlete-physician Herodicus, who wins fame and money through his athletic prowess and medicine, then proceeds to spend all his wealth trying to preserve his youth. This is what we mean by a disordered mind. He has been trained in the STEM fields of his time, and his training gains him great wealth, but it leaves him foolish enough to spend it all on something he can never buy."

From my latest article, co-authored with John Kaag, in The Chronicle of Higher Education. Read it all here.

Martin Luther on Liberal Education

-- Martin Luther, “To the Councilmen of All Cities in Germany that They Establish and Maintain Christian Schools,” in AE 45:357 (1524) (emphasis added) A full translation of the letter is available here.

Thoreau on Liberal Education, Wealth, and Freedom

-- Henry David Thoreau, "The Last Days of John Brown"

Gifts From My Father

The same is true for children: give them a hand lens, or an insect viewer, or a microscope with some prepared slides, and the world will suddenly become new to them. Dad planted that seed in me long ago. Now I carry a hand lens with me almost everywhere I go. I suppose the whole of my career is a reflection of the things that delight Dad and provoke his curiosity; most of them delight me and make me curious, too. And just as Dad passed on his curiosity to me, now it is my turn to pass it on to others.

Racism, Samaritans, and Saints

The closest I've come is this: when my kids were little, I taught them that despite what others may say, there are no bad words; but there are bad uses of good words. When we use our words to hurt others or to deprive them of what they need to grow and flourish, we are using our words badly.

Plainly there are acts, institutions, rituals and monuments that foster an undeserved poor view of some of our neighbors. Those should be changed or abolished.

But I don't think that's enough, and those might be more like symptoms than the illness itself.

I think we need to work to make sure we use our words in ways that help and heal, nurture and teach. I think we need leaders (at all levels) who will take positions of leadership as opportunities to edify and promote those who have not had such opportunities yet.

To put it in simpler terms, I think we need to work harder at loving our neighbors. Jesus told a story about this once, focusing on established ethnic hatred with deep political roots. I refer to the parable of the "Good Samaritan." This parable is the best answer I've got so far to the question I have posed for myself. If you've got the power to help others, and you see others needing help, then help them without regard for what it costs you. This is not easy, but it's what I want to strive for.

What do you think? What am I forgetting? Am I too naive and optimistic? I welcome thoughtful replies that show kindness towards a wide range of readers. (If you want to simply cuss me out or insult my ignorance, please save that for a direct message, or let me take you out for a beer or coffee so you've got more of my attention. Thanks.)

Liberal Education And Freedom

H.D. Thoreau, "The Last Days of John Brown"

Nature As A Classroom

These are not always easy conditions. Many hard-working Guatemalans live in poverty that is hard to conceive in our country; it is hot and wet except for when it is cold and wet; biting insects are everywhere; disease and snakes and thorny vines like bayal are constant threats.

But it is also a beautiful place with astonishing biodiversity and remarkable people whose resilience and generosity always make me want to improve my own character. They welcome us into their homes and into their lives, and they are glad to see us come to appreciate the place they live.

I expect that my students will forget much of what I say in my lectures and much of what they read in books. But I doubt very much that they will forget the people they have met here. Guatemala has gone from being an abstraction to a concrete reality. When they meet kind people of good character who have walked across Mexico and made it into the USA only to be caught and deported, "illegal immigrants" now have a face, a home, a family at whose table my students have received a nourishing and welcoming meal.

Likewise, they will not likely forget the sound of howler monkeys at night or the experience of scrambling up Maya temples still covered in a thousand years of trees and soil. They won't forget the long walk in a deep green forest and the smells of tortillas and beans cooked over a wood fire.

It is expensive to bring students so far. One could object that the money could be better spent on viewing the forest online or donating it to rainforest conservation. I disagree. I'm not in the business of dispensing information; I'm in the business of transforming lives, and not much transforms like full-bodied experience. Before we leave for Guatemala my students read papers written by wildlife conservation researchers. In Guatemala they meet those researchers in person and get to hear their stories. They hear in their tone and see in their eyes what brought them to Guatemala and what keeps them here. In such times my students go from taking in data to rethinking their lives.

It is my hope - my exuberant, perhaps not wholly rational hope - that out of such lived experience of nature my students will become people who comfort orphans and widows in their distress, who receive the foreigner into their own homes, who marvel and the world's diversity and who, for the rest of their lives, work to preserve it.

The Trivium And The Quadrivium

At some point in the Middle Ages, through a slow process of growth and refinement, educators came to identify seven arts that were considered liberal. The seven liberal arts were the arts practiced by people who were, or who would be, free. (The Latin word liber can mean "a free man.")

The liberal arts were divided into two groups: the trivium and the quadrivium. As the names suggest, the trivium included three arts, and the quadrivium included four.

The trivial arts sought to teach eloquentia, or eloquence, the proper use of words. The quadrivial arts aimed at sapientia, or sapience, the proper use of numbers.

In each case there is a natural progression, beginning with the rudiments and building on those foundations to help the student master eloquence and sapience.

The Trivium and the Quadrivium (and how they are built)

The trivium proceeds like this:

The quadrivium proceeds like this:

But Is Any Of This Relevant?

It's not hard to see that a lot of this is outdated, especially in the quadrivium, which was like the STEM of the Middle Ages, focusing on mathematics, engineering, and natural sciences. We no longer believe in the "music of the spheres" or that the motion of astronomical bodies is governed by harmony akin to music. And our sciences and humanities have grown to include many other disciplines that (at least at first) don't seem to be included here.

It's also not hard to see that some of the way we educate today still has echoes of this structure. For instance, until recently, we called children's schools "grammar schools," and this is why.We still consider it important to begin important enterprises with teaching the relevant vocabulary, grammar and logic: we often begin classes by introducing new vocabulary, and we begin contracts by defining terms.

And while we don't think of outer space as being a set of nested, harmonious spheres governed by intelligences who receive their direction from the Empyrean, we do think number is extremely important as a tool for discovering how nature works. This may seem like the most obvious of points, but that is because the idea has pervaded our thinking. It's a good idea, and it stuck. Similarly, we have the hunch that inquiry into the nature of things will in fact be met with answers. Again, this seems obvious, but not every culture has thought so. The idea has stuck, and it has paid off.

Yes, But Only If You Care About Science And Freedom.

In my view, the trivial arts and their organization remain as relevant as they once were, for three reasons.

First, every free person needs to know how words are used. If you don't learn to use them, and then practice with them, you will be easily misled. If you don't study persuasion, you are far less likely to know that you are being persuaded.

Second, and related to the first point, the sciences depend upon the trivial arts. Students who cannot read and write cannot learn effectively.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, long study in the humanities leads one to consider both the way words are used for persuasion and the ethics of persuasion. People who are trained in the conclusions of the sciences are not scientists, they are databanks. People who are trained in some of the methods of the sciences are technicians. Databanks and technicians are useful to other people. But what we need are people trained in the scientific method, which, by the way, is not something we get from the sciences. It is tested and approved by the sciences, but the natural sciences do not give it to us. Which of the natural sciences could discover a scientific method, after all? Scientific method is about the proper handling of data, the examination of claims and propositions, and the distribution of relevant conclusions. Look back at the description of the trivium and the quadrivium and you'll see that this is the work of the former, not of the latter.

The Real Crisis In The Humanities

There is a lot of talk these days about the crisis in the humanities. The money is all in the sciences, and smart students should go there to study, we are told. College administrations look to humanities departments as service departments to bolster the offerings of the science departments, who do the real work of the university.

I actually don't dispute this view, even though I'm in the humanities. It's quite obvious that much of the money is in the sciences, and I think that smart students should study the sciences. That's because I think every student should study the sciences.

But I also think that smart students should engage in long study of the humanities. The sciences depend upon the humanities, just as the quadrivium was legless without the trivium. More importantly, people who want to be free -- that is, people who do not wish to be persuaded without their consent, people who wish to think for themselves, people who wish to wield tools and not just to be the tools of others -- these people need to study the humanities.

The crisis in the humanities is that even in the humanities we've allowed ourselves to forget how interrelated all the disciplines are. It's time to brush up our eloquence, for the sake of our students, and take this message to our schools.

*****

Addendum: A friend wrote to me and pointed out that I called the second part of the Trivium "logic" when I should have named it "dialectic," which includes both logic and disputation. I don't dispute his correction.

I've also since discovered Dorothy Sayers' "The Lost Tools of Learning," an illuminating essay on the medieval liberal arts. I wrote this post hastily, after a meeting at my college where the question of what an education ought to do was under consideration. I wanted to make a thumbnail sketch of the Trivium and Quadrivium for my colleagues, and this was the result of some quick typing in the last few minutes of the workday. A fuller picture would have included C.S. Lewis' essay "Imagination and Thought in the Middle Ages," and at least some mention of Martianus Capella. Maybe another time I'll return to this topic and write that fuller essay. For now, these references will have to suffice.

Camping With My Students: Stargazing in the Badlands

|

| We set up tents, but we rarely use them. Much nicer to sleep under the stars. |

Each fall I look for an ideal weekend to take my Ancient and Medieval Philosophy students stargazing. An ideal weekend counts as one where we will have clear skies, a new moon, and reasonably warm weather so we can spend a lot of time outside.

Several times over the last ten years, the weather's been so good that we've been able to go out to a primitive campground (i.e. one where there is no electricity and almost no urban glow) in the Badlands National Park.

On such nights, in such places, the sky glistens with stars. The Milky Way is a bright band across the night, and meteors punctuate our views each hour.

I tell my students that this is an optional trip. They don't get credit for coming, and they don't lose any credit for staying home. It's a four-hour drive from our campus, so it's a real commitment of time on their part. Their only rewards are these: an experience of what the Norwegians call friluftsliv, a beautiful night under the stars in a remote and lovely place, and free pancakes at sunrise, cooked by me.

And yet every time I offer this trip, half a dozen or more students - and sometimes other professors - tag along.

|

| The stop sign is just a scratching post to this bison. |

I've written before about the importance of teaching outdoors and of doing labs in philosophy. Experientia docet, experience teaches us. What we learn through lived, full-bodied experience tends to stick with us far better than what we simply hear spoken from a lectern or see on a PowerPoint slide.

We go out there, ostensibly, to see the stars. This is because I want my students to watch the skies and to imagine what it would have been like for ancient and medieval philosophers like Thales, Plutarch, Ptolemy, Eratosthenes and, even Galileo (on the cusp of the Middle Ages) to gaze at the skies and learn from their movements.

But we are really there for other reasons that are easier to show than to tell. I want them to see that ideas do not grow up in a vacuum, and that the artificial divisions between academic disciplines are really artificial and convenient. Educated people should care about all the disciplines. We should not allow them to be compartmentalized, as though philosophy and sociology had nothing to do with accounting, or physics, or poetry.

Aristotle tells us that the love of wisdom begins in wonder. I will add that experience of new things can be the beginning of wonder.

Many of my students have never heard coyotes sing. In the Badlands, they trot past our cots and tents and sing to us all night long. When we wake in the morning, we are often surrounded by small groups of bison, slowly grazing their way along the hillsides. After breakfast we climb the steep slopes and find ancient fossils.

I don't know if any of this is a desirable or assessable outcome for a philosophy class. Also, I don't care. Because all of these things are, I think, desirable outcomes for life.

Because I believe that "it is beautiful to do so" is reason enough to sleep under the stars.

College Football and Moral Education

Whenever I read an article in the local paper about a local talented high school athlete who has signed with a college sports team, I wonder why we don't report that a local talented debater, chess expert, or math student just made it into Harvard or the University of Chicago on the basis of her talent. It makes me wonder: Do we not care about intellectual ability as much we care about physical prowess?

In 1908 Harvard Philosophy professor Josiah Royce published an essay entitled "Football and Ideals." The essay is over a century old, but the topic and the ideas sound like they could have been written yesterday. Royce writes, "Football is at present a great social force in our country. It has long been so. Apparently it is destined to remain so." So far, this is correct.

In Royce's time football was still largely a college sport. (The NFL was founded twelve years later.) Just as college sports in the United States do today, it drew big crowds. Just as in our time, football had its scandals: severe injuries among players; hooliganism among the crowds; and unethical behavior among players off the field and among fans and gamblers.

And just as in our time, supporters of the sport claimed that football did more social good than harm.

In his essay, Royce takes all of this seriously. Any social force this great deserves to be examined, Royce says, in order to determine what social goods it provides, and at what cost. Only a few play, but all of us are affected by the sport. He puts it like this:

"Football must be estimated as to its general relations to the welfare of society, just as Standard Oil, or just as the railway management which results in killing a larger proportion of railway passengers in our country than in other countries, must be estimated; it must be judged by non-experts, precisely in so far as it influences their great common social concerns."Royce was in one sense a non-expert inasmuch as he was a professor, not a college athlete; but in another sense he was an expert because he had devoted much of his research to this question of ethics and the common good. Royce held that the aim of our moral lives is the fostering of loyalty, and that we can see this in a range of social institutions. He wasn't arguing that we should aim for small and local loyalties, though, but for loyalties that, though they begin and are expressed locally, develop into a broad agape-like loyalty that includes all people.

We often hear this expressed in similar terms today when proponents of college sports say that participation in sports fosters virtues like teamwork, or school spirit.

I think participation in athletics actually can do even more than this. As an educator, I have noticed that college athletes are often some of my most disciplined students. In general, they wake up early, take care of their bodies, and get their work done. There are exceptions, of course, but this has been the case with most of my student-athletes, anyway. Perhaps this is because I teach philosophy, and the weak students shy away from it because it is a difficult subject with no obvious cash value for their lives. In any event, my student athletes generally keep up the "student" part of that title fairly well. Being an athlete can provide numerous benefits for a student.

But this is only a small part of the question, isn't it? Royce reminds us that the question we are asking is not "Does playing football help the student-athlete?" but "Does football on campuses make us and our communities better?" In other words, this is not a question about the athlete but about the spectators. It is really a question about us.

This question is not a soft, squishy, depends-on-what-you-mean question. Royce has something very specific in mind: does the example of others' athleticism make you more ready to "go and do likewise," or does it merely thrill you? Or does it even sap your desire and ability to demonstrate similar excellence and loyalty?

Royce says that "if a man has only taught you to cheer him, he has so far only amused you," and if football has only allowed you to "let off steam" without making you "more practically devoted to your own tasks," then it has not made you better but possibly it has even stripped you of your moral strength.

This requires honest self-assessment. When you watch football, or other athletic contests (like the World Cup) are you becoming a better person, one more able to devote yourself to the tasks that strike you as worthy of your energies? Are you developing a deeper loyalty to others, and deeper respect for the loyalties of others, or does fandom in fact make those goals more difficult to attain?

Note that this is not a critique of football as a game, nor even of college sports as an institution. It is a critique of the spectators, and of the effect sports have on us when we watch them. Are they making us more fit for life together, or are they in fact making us less so?

I will not try to answer that question for now. Royce's conclusion, in his time, was that the conditions of spectating made football unfavorable "to the best moral development of our youth." College sports may be great for the players, but not for those who do not play, he said.

It's not obvious to me that things are now as they were then, but it is obvious to me that football has become a greater social force than it was in Royce's time a century ago. If so, it merits our constant examination. And if we are honest, and good, we will not be content with vague observations about building teamwork in the players. After all, the players never play alone, but always with a crowd. It is not just two teams who play a football game, but those two teams play together with the combined energies of the crowd, and each influences the other.

This should be obvious to us from the simple fact of team selection. Coaches select players from the general body of students (or potential students) in order to win games for the school, not in order to help those select few become better people. At many high schools and colleges, coaches are considered teaching faculty. But there is this important difference between sports teams and academic classes: academic teachers are not permitted to choose which students they will educate, but coaches generally have free rein to eliminate from their tutelage any whom they choose. So while college sports may be similar to classes (inasmuch as they purport to teach) they differ significantly in this respect.

For myself, I am not opposed to college sports. If anything, I would like to expand them to include all students as players, not merely as spectators. After all, if there are moral benefits to playing sports, then why would any institution of higher education not want to urge all of its students to gain that benefit by playing?

Newspapers, Sports, and Healthy Societies

I have caught some of de Tocqueville's enthusiasm for the way journalism can pump the lifeblood of a free society. Subscription to one's local paper is an act of patriotism. It is a commonplace of contemporary life in the United States to say that our freedom is won and preserved by soldiers. But this is, at best, only partly true, and history shows that armed men can both help and hinder freedom. Armies may be helpful, but there are other services that are more essential to freedom: lawyers, educators, and journalists.

But my idealism concerning journalism contends with my cynicism. Publishers of news are, after all, publishers; and publishers must pay their bills, too. They've got to sell ads, which means they can't risk offending those who buy ads. Right now we are in one of those times when there are a very few companies that own very many of the news outlets, and it's hard to imagine that doesn't affect both the slant of news stories told and the way those stories are selected and omitted in the first place. And they've got to print what we want to buy.

All this is a prelude to something else I have in mind to write over the next few days, about the relationship between sports and education, a question at least as old as Plato's Republic. I begin here by noting the role sports play in our news. How much of television news is devoted to sports? On any given day, a third of my local newspaper reports local and national and international sports stories.

This raises several questions for me. Why does this hold such fascination for us? And is our fascination with sports healthy?

Since some of what I will say about sports will seem critical, let me point out that I'm not opposed to sports. I'm a member of a society devoted to philosophy and sport, and I love outdoor recreation. I swam for the varsity team in my high school; I played club ultimate in college; I encouraged my kids to play various sports like flag football, gymnastics, little league, and soccer throughout their youth; and I am now the faculty advisor for my college's martial arts club and I am a U-19 recreational league soccer coach in my city. Sports are important; but that does not mean that all the attention we give to sports is well given.

So, once again, I begin with noticing the attention our newspapers give to sports. Plainly we need our journalists to attend to judges and legislators, to governors and police departments, because all of those are public offices endowed with public trust. Journalists are one of the main ways we prevent the violation of that trust. So what about sports? Is the presence (we could even say the domination) of sporting news merely a distraction from the real work of journalism? Is it a necessary evil to get us to buy the paper and to support the important democratic work of reporting?

One could argue that we need newspapers to watch athletes and coaches and owners of athletic teams to ensure that their influence on society is not unjust. But this cuts both ways: were it not for the attention we already give to sport, the influence of athletes, coaches, and owners would be minimal. The fact that newspapers report so much about sport is the symptom; we ourselves, and our attention to sport are the cause. It is not something called "sport" that is at issue here, nor the leaning of the journalists, but rather, the attention we ourselves pay it. If newspapers are physicians of our civic life, then we are the patient; and the doctor can only do so much to make us healthy if we will not do our part, too.

Contemplation, Conversation, Commentary

To paraphrase Plutarch’s famous line about education, the mind is not a vessel to be filled but a fire to be kindled. A jar that is filled by someone else only contains what is put into it; it becomes a place of storage. It is a useful tool, but it does not increase what it holds. A fire, on the other hand, gives off heat and light, and that heat and light can kindle other fires and illuminate distant obscurities.

I think education should be like this, a process that pays continual returns if it is well tended.

Of course, unchecked fire can do great harm, and education without boundaries is like a fire with no hearth or stove.

Should Education Have Boundaries? A Reflection On My Own Classrooms

But how can we put boundaries on education? One way, of course, is to limit education to memorization, tool-and-skill training, or indoctrination. But each of these amounts to filling a vessel. That is, it amounts to filling students’ minds with facts, opinions, or skills, without giving the students what they need to examine or improve what they are given, and to teach others what they have learned.

My aim as a teacher is to offer students liberal arts in such a way that they gain both practical skills and the means to improve those skills as the use and teach them. I say liberal arts because I do not wish my students to be the servants of others, but to be people who practice responsible liberty and who help others to do the same.

Of course, unchecked liberty can do great harm, and liberal education without boundaries is like a fire without a hearth. In one direction lies the restraint of being the mere vessel of others’ doctrines; in the other direction lie the perils of life beyond the bounds of ethics.

Fortunately, this is not a new problem, but a very old one. This means that there are some old and time-tested means of education that help us to find the mean between the extremes.

What I try to practice in my classes is something I see – in varying degrees – throughout the history of education. I will summarize it in three words: contemplation, conversation, and commentary.

Contemplation

By “contemplation” I mean the practice of examining what is already understood by the community of inquiry. What do we know? What are the tools we have at hand? What are the problems we wish to pursue together, and what solutions have been put forward so far? Learning these things is the first step, akin to learning the language when you move to a new country. It involves some memorization, and it involves learning the rules by which others conduct their lives and research. This is like learning the basics of a science, plus the methods used by scientists; or it is like learning the basics of poetry, plus the methods of reading and writing. Each discipline has its content and its tools, its history and its methods, its canonical texts and its rules and rituals for learning those texts. In my philosophy classes this means reading the assigned texts thoughtfully so that you come to class ready to ask good questions about them. In my language classes it means working through grammar and translation exercises, and memorization of vocabulary and inflections. In my environmental studies classes, this means learning basic taxonomy, ecology, geology, law, and policy, so you can discuss these things with others who know more than you do. In each discipline it will involve different things, but the general rule holds: if you want to join the community, you’ve got to learn these things first, just as you have to learn grammar before you can converse with others. And conversation is the next step.

Conversation

By “conversation” I mean coming together with others to think about the rules and tools we have been given. This is more than speaking with friends; this involves serious grappling with issues in the company of our contemporaries. In my philosophy classes, this means asking good questions about what you’ve read the night before class. It means exposing your ignorance and asking others to help you to correct it. It means taking others seriously as people who might see what is hidden in our blind spots. In my environmental humanities classes, this means going into the field with your classmates in order to examine the world together. In my philosophy of religion classes, this means engaging in the hard work of talking about the divine in a way that takes others seriously. Their questions might just be the questions you need; their insights might serve you well. It would be unwise to decide in advance that others have nothing to teach you; in each discipline, you’ve got to take time to do research, whether in the lab, in the field, in convivial conversation and deliberation with others. And then, when you’ve done that well, you’re ready to offer commentary on what your new insight means for us all.

Commentary

This is what I mean by “commentary,” then: the slow consideration of what consequences we might expect from what we have learned so far, and the offering of that consideration to others, so that they can contemplate and deliberate on them, and offer new commentary of their own.

Learning As A Cycle, And As A Shared Process

If you’ve done a good job with the first two steps, the third step leads you back to the first step. Good researchers who publish what they have learned contribute to the body of knowledge that others can use to kindle new fires that warm new homes and light new paths.

Another way of thinking about these three steps is that it concerns thinking about different times. The first step is the consideration of the past; the second involves taking seriously the present time and our contemporaries as fellow learners; and the third step is mindful of the future.

You might also think of this as a process of thinking at different speeds, and from different perspectives. The first step is often quite slow at first, and it requires us to learn to see as others saw, even if their way is not our own. The second step might happen quite quickly, whether in a sudden insight in the laboratory or in a fast-paced debate. The third step often requires the very slow work of painstakingly careful thinking and clear writing.

Of course, these three steps are not discrete. Often, they overlap and intermingle. We might discover in debate or in the field that we have failed to learn something important. Or our contemplative work might send us back to reexamine our research, or even to start over with new tools and insights. But on the whole, I think these three facets of learning wind up being repeated over and over in each field, and by connecting us to other people in the past, present, and the future, they offer a sort of bounded liberty to our learning.

Slow Thinking, Quick Writing, and Slow Assessment: On The Importance Of Self-Discipline

Much of what I hear and read about education has to do with metrics intended to assess the value of certain kinds of practices. I see the merit in many of those metrics. Sometimes, though, it seems that the metrics become a quick substitute for other kinds of evaluation that are harder to put into numerical or measurable form. We don't like the slow process of contemplation, or of commentary. We do like it when others put things in simple forms that we can quickly compare. There's value in that, but if we don't do our own contemplation and commentary, we abdicate a good deal of our involvement in our own learning, and we shift from being fires to vessels.

I am writing this piece fast, because I have a discipline of trying to write all my blog posts in less than fifteen minutes. (I do sometimes return to them to edit them for clarity or to add relevant information.) My aim here has been to write quickly about something I have thought about slowly. In other words, I've contemplated this for years, and today I'm writing a bit of quick commentary to contribute to our shared conversation. My quick writing is intended to be a moment of distillation of a cloud of contemplation. Too much time with my head in the clouds can obscure my vision; at some point I need those clouds to precipitate into more concrete thoughts. Writing helps me to do that.Your thoughtful replies and insights will hopefully help to kindle new fires.