mountains

∞

Interview on SD Public Radio

Karl Gehrke interviewed me on SD Public Radio today about my new book. We talk about the book, brook trout, fly-fishing, hunting, raising children, and a handful of other topics with occasional nods to Heidegger and Bugbee, Kathleen Dean Moore, Scott Russell Sanders, and, of course, Thoreau.

Click here to listen to the whole interview.

Click here to listen to the whole interview.

∞

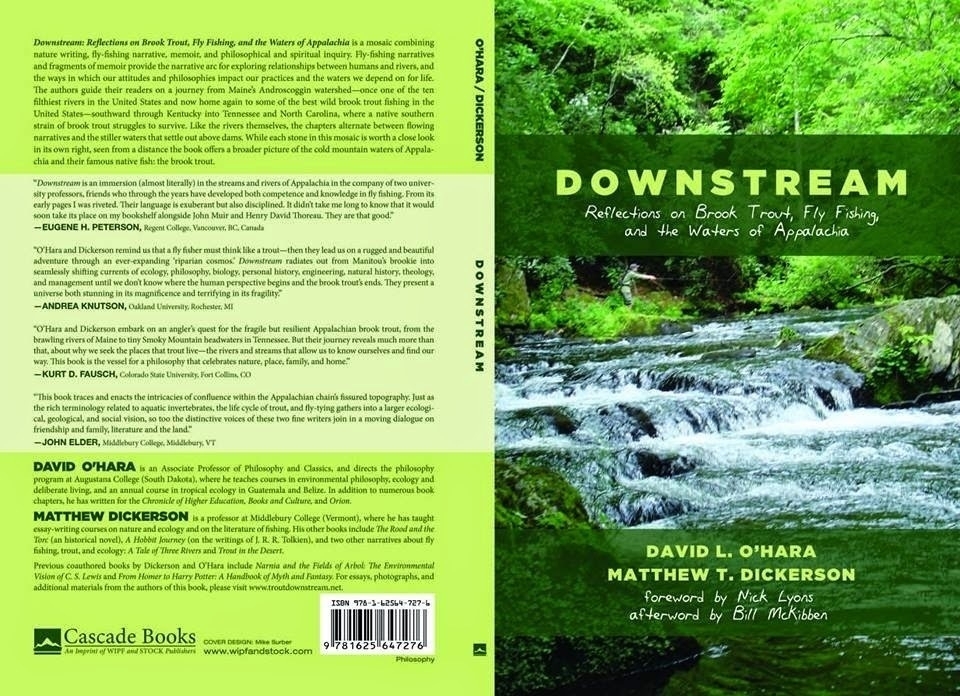

Downstream: My New Book On Brook Trout and Appalachian Ecology

You can find it here, on the publisher's website, for a very reasonable price.

It is now listed on Amazon as well, though not yet in stock there.

I'm very grateful for the foreword by Nick Lyons, the afterword by Bill McKibben, and the kind words offered by such a wide range of brilliant scholars of theology, literature, and science, like Eugene Peterson, Andrea Knutson, Kurt Fausch, and John Elder.

It is now listed on Amazon as well, though not yet in stock there.

I'm very grateful for the foreword by Nick Lyons, the afterword by Bill McKibben, and the kind words offered by such a wide range of brilliant scholars of theology, literature, and science, like Eugene Peterson, Andrea Knutson, Kurt Fausch, and John Elder.

∞

The Place Where I Live - In Orion Magazine

Here is a short piece I wrote for Orion Magazine, along with a few of my photos from around Sioux Falls. It will appear in the print edition later this year.

∞

Free Stone

One spring after heavy rains had come and gone, my father and I walked the banks of the Sawkill Creek. It was newly scrubbed by floodwaters that had gouged its banks, sweeping away trees, glacial deposit boulders, and even a few buildings as the Catskills shed the rainfall and shot it down to the Hudson.

The memory of that short walk remains one of the strongest from my childhood. The river had cut new banks, and had changed its own course. We walked along the round gravel banks and gazed up at the undercut roots of massive oaks and pines. We saw the bones of the earth laid bare by the river's irresistible blade. The river had cut itself a new bed. Everything in its path was destroyed; everything in its path was made new.

Since then I have walked hundreds of miles along - and often in - deep, clear waters over cobbled riverbeds. The sound of the water is the music of my soul, high sprinkled notes of splashing water and bass tones of massive stones rocking back and forth in the current. Walking in freestone streams makes me forget my worries, forget time itself.

The memory of that short walk remains one of the strongest from my childhood. The river had cut new banks, and had changed its own course. We walked along the round gravel banks and gazed up at the undercut roots of massive oaks and pines. We saw the bones of the earth laid bare by the river's irresistible blade. The river had cut itself a new bed. Everything in its path was destroyed; everything in its path was made new.

|

| Polished by the river. |

Since then I have walked hundreds of miles along - and often in - deep, clear waters over cobbled riverbeds. The sound of the water is the music of my soul, high sprinkled notes of splashing water and bass tones of massive stones rocking back and forth in the current. Walking in freestone streams makes me forget my worries, forget time itself.

∞

Perpetual Motion

As the sun sets it sends its last rays shooting up from below the horizon to illuminate the undersides of contrails, the warp and weft of high-altitude aircraft that have crushed the air before them and left a trail of disturbance behind to mark their racing progress.

I myself am a frequent traveler. My far-flung family and my work as an educator, writer, and lecturer mean I am often in airports. At those times, I am mostly concerned with making my next flight. But when I gaze at the evening sky from my kitchen window and see the silver lines glowing over the setting sun, I wonder: where are we going? And why are we in such a hurry to get there?

Mise En Place

I recently read an interview with Scott Russell Sanders in the Englewood Review of Books. In it Sanders talks about the virtue of living in one place for a long time, of "Staying Put."

We Americans seem to be constantly on the move. We began as a nation of movers, and we have filled a continent by our frenetic motion.

When I took the job I currently have, my wife and I were moving to a part of the world we'd never even visited, the prairies of the upper midwest. We knew nobody here, had no roots here. We left our home and friends and family to find work, and we thought it would be a temporary assignment, a sojourn from which we would return to the place where we, like seeds from a tree, first fell to earth.

Little by little I am coming to think I am not on a sojourn here but am a transplant.

Taproots

I long for the mountains and clear streams of my youth. But when I think of myself as a temporary resident, I find it harder to put down taproots that can drink deeply from the waters that flow far underground.

The danger? Plants with shallow roots cannot weather droughts as well as those with deep roots. By analogy, as we commit ourselves to the place we live in, the more strength we can draw from that place.

And plants with taproots are good for the soil, too. They break the hard clay and bore holes into which the rain can sink deeply. Behold the lowly dandelion, the maker of topsoil. If I sink roots here, I'll make it more likely that my community will benefit from my presence.

This sinking of roots is hard to do. It can be hard because the culture may be different, for instance. Eight years into this gig, I still struggle with midwestern indirect communication, and with the very, very slow process of getting to know native midwesterners.

Weaving Our Hearts

Of course, being surrounded by others who are also on the move makes it hard, too. When I was in grad school one of our neighbors, Lisa, told us she could not be our friend because she knew we were only there for five years. We shared a backyard, and our children played together, but Lisa knew that too many times she had allowed her roots to grow into the lives of other mobile academics, and when they were uprooted, so was her heart. It hurt to hear her tell us that, but who could blame her?

And it is hard for me not to be near mountains. Sometimes, gazing out that kitchen window in the summertime I see great thunderheads low on the western horizon, gathering strength as they roll across the prairie towards Sioux Falls. My heart so longs for the mountains that nearly every time I see those thunderclouds I let myself believe for an instant that they are solid mountains, not ephemeral, gauzy clouds. I would sooner believe in a cataclysmic upheaval of the earth than believe I am without mountains forever.

Sometimes people here try to comfort me by telling me that here, in this same state, we have the Black Hills. I know they mean well, and I know it's a point of pride for them, but those mountains are over three hundred and fifty miles away. I cannot see them from here, and for some reason, that matters. It's like telling a hungry person to take heart, because somewhere else, somewhere not here, there is a banquet. It only makes the pangs sharper.

The Mountains Underground

My heart leans towards the mountains, but for today - the only day I have any control over, and a limited control, at that - I am trying to turn my feet into roots.

Years ago, when I was working in Poland, a friend brought me to a place called Tarnowska Góra. There's a silver mine under fairly flat ground there. Knowing that góra means "mountain," I asked her "Gdzie jest góra? Where is the mountain?" She smiled, and pointed down at her feet. "Underground," she said.

This is the image I am trying to cultivate: here there are mountains, too, but like the hidden thoughts of coy midwesterners, they are concealed by the superficial appearances.

These mountains under the prairie are not the Adirondacks of New York, or the bold Catskills fringing the Hudson River, whose heights cannot be avoided. They are not the Sangre de Cristo mountains or the Green Mountains or the Alleghenies, each of which have been my home, places where my children were born and raised. These subterranean mountains wait quietly beneath, supporting all things evenly, deeply rooted, immovable. I cannot gauge their height with my eye; I must measure it patiently, with my feet, by walking the slow prairie, by standing still. And, perhaps, though my heart is not yet ready to accept it, by letting my body one day be buried here, adding my small mass to these mountains, raising them incrementally by the simple height of my dormant bones.

But that is for another day. Today, I will walk, and let my feet learn to feel the mountains below.

All The Mountains Are Underground Here

|

| Sunset over the Yellowstone River |

As the sun sets it sends its last rays shooting up from below the horizon to illuminate the undersides of contrails, the warp and weft of high-altitude aircraft that have crushed the air before them and left a trail of disturbance behind to mark their racing progress.

I myself am a frequent traveler. My far-flung family and my work as an educator, writer, and lecturer mean I am often in airports. At those times, I am mostly concerned with making my next flight. But when I gaze at the evening sky from my kitchen window and see the silver lines glowing over the setting sun, I wonder: where are we going? And why are we in such a hurry to get there?

Mise En Place

I recently read an interview with Scott Russell Sanders in the Englewood Review of Books. In it Sanders talks about the virtue of living in one place for a long time, of "Staying Put."

We Americans seem to be constantly on the move. We began as a nation of movers, and we have filled a continent by our frenetic motion.

When I took the job I currently have, my wife and I were moving to a part of the world we'd never even visited, the prairies of the upper midwest. We knew nobody here, had no roots here. We left our home and friends and family to find work, and we thought it would be a temporary assignment, a sojourn from which we would return to the place where we, like seeds from a tree, first fell to earth.

Little by little I am coming to think I am not on a sojourn here but am a transplant.

Taproots

I long for the mountains and clear streams of my youth. But when I think of myself as a temporary resident, I find it harder to put down taproots that can drink deeply from the waters that flow far underground.

The danger? Plants with shallow roots cannot weather droughts as well as those with deep roots. By analogy, as we commit ourselves to the place we live in, the more strength we can draw from that place.

And plants with taproots are good for the soil, too. They break the hard clay and bore holes into which the rain can sink deeply. Behold the lowly dandelion, the maker of topsoil. If I sink roots here, I'll make it more likely that my community will benefit from my presence.

This sinking of roots is hard to do. It can be hard because the culture may be different, for instance. Eight years into this gig, I still struggle with midwestern indirect communication, and with the very, very slow process of getting to know native midwesterners.

Weaving Our Hearts

Of course, being surrounded by others who are also on the move makes it hard, too. When I was in grad school one of our neighbors, Lisa, told us she could not be our friend because she knew we were only there for five years. We shared a backyard, and our children played together, but Lisa knew that too many times she had allowed her roots to grow into the lives of other mobile academics, and when they were uprooted, so was her heart. It hurt to hear her tell us that, but who could blame her?

And it is hard for me not to be near mountains. Sometimes, gazing out that kitchen window in the summertime I see great thunderheads low on the western horizon, gathering strength as they roll across the prairie towards Sioux Falls. My heart so longs for the mountains that nearly every time I see those thunderclouds I let myself believe for an instant that they are solid mountains, not ephemeral, gauzy clouds. I would sooner believe in a cataclysmic upheaval of the earth than believe I am without mountains forever.

Sometimes people here try to comfort me by telling me that here, in this same state, we have the Black Hills. I know they mean well, and I know it's a point of pride for them, but those mountains are over three hundred and fifty miles away. I cannot see them from here, and for some reason, that matters. It's like telling a hungry person to take heart, because somewhere else, somewhere not here, there is a banquet. It only makes the pangs sharper.

The Mountains Underground

My heart leans towards the mountains, but for today - the only day I have any control over, and a limited control, at that - I am trying to turn my feet into roots.

|

| A picture of my heart: my boys, and mountains beneath them. |

Years ago, when I was working in Poland, a friend brought me to a place called Tarnowska Góra. There's a silver mine under fairly flat ground there. Knowing that góra means "mountain," I asked her "Gdzie jest góra? Where is the mountain?" She smiled, and pointed down at her feet. "Underground," she said.

This is the image I am trying to cultivate: here there are mountains, too, but like the hidden thoughts of coy midwesterners, they are concealed by the superficial appearances.

These mountains under the prairie are not the Adirondacks of New York, or the bold Catskills fringing the Hudson River, whose heights cannot be avoided. They are not the Sangre de Cristo mountains or the Green Mountains or the Alleghenies, each of which have been my home, places where my children were born and raised. These subterranean mountains wait quietly beneath, supporting all things evenly, deeply rooted, immovable. I cannot gauge their height with my eye; I must measure it patiently, with my feet, by walking the slow prairie, by standing still. And, perhaps, though my heart is not yet ready to accept it, by letting my body one day be buried here, adding my small mass to these mountains, raising them incrementally by the simple height of my dormant bones.

But that is for another day. Today, I will walk, and let my feet learn to feel the mountains below.

∞

People Of The Waters That Are Never Still

Generations ago, one of my European grandfathers and one of my Native American grandmothers married, fusing in their offspring two peoples who had parted ways ages before, one heading west to the British Isles, the other to the Bering Strait and across to North America. I grew up in New York, near where they met and married, and my childhood is marked by memories of that land: tall oaks and white pines, deep forests, rocky crags over which the water pours, never still, always the same, always changing. The waterfalls of the Catskill Mountains are a constant presence in those mountains and in my memories. They are the waters of my mothers and fathers, and of my youth.

My family has since lost the languages those ancestors spoke, and this fusion of tribes has adopted the linguistic fusion of English. I have no intention of claiming a legal place among either of the nations from which I am descended, nor even to name them here. But I find that the memory of both, and of the lands they lived on, is rooted deeply in my consciousness of who I am. Last year, while visiting the British Museum, I saw a display of various Native American peoples, including my own. It was the only time a museum has moved me to tears. The words and ways of my forebears may be mostly gone, but they are not forgotten. My father taught me to remember them and what they knew of the land we lived on, and often, while teaching me to know the woods, he would remind me that those woods were old family acquaintances.

Jacob Wawatie and Stephanie Pyne, in their article "Tracking in Pursuit of Knowledge," cite Russell Barsh as saying that "what is 'traditional' about traditional knowledge is not its antiquity but the way in which it is acquired and used." Our word "tradition" comes from Latin roots that mean something like "giving over" or "handing down." Traditional knowledge is knowledge that is a gift from one generation to the next, a gift we give because we ourselves were given it. I am grateful to my father, in ways that I may never have told him - in ways that perhaps words cannot begin to tell - for the traditions he learned and loved and passed on to me. I'm grateful that he has not let me forget.

There is, of course danger in emphasizing one's heritage and one's roots, especially if we make that the source of a distinction between ourselves and others, or a way of diminishing the lives and traditions of others. Just as much as it matters to me that I am from the people of the waters of the Catskills, it matters to me that my ancestors shared those waters with one another, people from two continents recognizing, each in the other, the waters from which both arose.

For all that I have received, for the traditions like waters pouring over the cliffs, gifts like the Kaaterskill Creek, let me give thanks. Let me give thanks with my life, offering to those who come after me, a taste of the sweetness of those same waters.

(Photo: Kaaterskill Creek in New York State)

My family has since lost the languages those ancestors spoke, and this fusion of tribes has adopted the linguistic fusion of English. I have no intention of claiming a legal place among either of the nations from which I am descended, nor even to name them here. But I find that the memory of both, and of the lands they lived on, is rooted deeply in my consciousness of who I am. Last year, while visiting the British Museum, I saw a display of various Native American peoples, including my own. It was the only time a museum has moved me to tears. The words and ways of my forebears may be mostly gone, but they are not forgotten. My father taught me to remember them and what they knew of the land we lived on, and often, while teaching me to know the woods, he would remind me that those woods were old family acquaintances.

Jacob Wawatie and Stephanie Pyne, in their article "Tracking in Pursuit of Knowledge," cite Russell Barsh as saying that "what is 'traditional' about traditional knowledge is not its antiquity but the way in which it is acquired and used." Our word "tradition" comes from Latin roots that mean something like "giving over" or "handing down." Traditional knowledge is knowledge that is a gift from one generation to the next, a gift we give because we ourselves were given it. I am grateful to my father, in ways that I may never have told him - in ways that perhaps words cannot begin to tell - for the traditions he learned and loved and passed on to me. I'm grateful that he has not let me forget.

There is, of course danger in emphasizing one's heritage and one's roots, especially if we make that the source of a distinction between ourselves and others, or a way of diminishing the lives and traditions of others. Just as much as it matters to me that I am from the people of the waters of the Catskills, it matters to me that my ancestors shared those waters with one another, people from two continents recognizing, each in the other, the waters from which both arose.

For all that I have received, for the traditions like waters pouring over the cliffs, gifts like the Kaaterskill Creek, let me give thanks. Let me give thanks with my life, offering to those who come after me, a taste of the sweetness of those same waters.