Socrates

- Richard Russo, Straight Man. This is one that has been recommended to me so many times by so many people I finally bought it and read it. If you work in a small college humanities department, trust me: you'll feel at home in this book.

- J. M. Coetzee, Elizabeth Costello. This is another that was recommended to me. It takes the form of a series of lectures delivered by a novelist, with very little framing around each lecture. The lectures stand alone, but all together they give the picture of an artist at work trying to figure out what exactly she is doing, what she believes, and why. Coetzee is really a philosophical novelist, and he does a remarkable job of engaging directly with figures like Descartes and Kant and Peter Singer.

- Dave Eggers, How We Are Hungry. Eggers' short stories are like David Foster Wallace's, but less frenetic and wild and so a little easier to read. I love the genre, and I'm always fascinated by people like Eggers and Wallace who explore its edges. I don't love this book, but it has kept my attention as a kind of intellectual exercise, and it is like a garden filled with tiny blossoms that delight the eye when you slow down and look closely.

- Matthew Dickerson, The Rood And The Torc. Dickerson is a friend of mine and my co-author, so there's my disclosure. Now let me say this about Dickerson: there are good reasons why he's my friend and my co-author, and this book illustrates some of them. He's a natural, easy storyteller who makes you glad you kept turning the pages. His prose is light, disappearing from the eye, easily replaced with a mental image of the place and the characters. This is one of several novels he has written about the peripheries of Beowulf, a beautiful story about poetry, songs, medieval Europe, and the cost of making the right choices. Reading this book was the first time I felt like I could see medieval life, not just read about it. Homes and hearths come alive with smoke and roasting meat and moving songs; the Frisian landscape and the rolling sea and the smell of cowherds seem to lift off the pages and into my imagination as I read it. John Wilson is right: this is "a splendid historical novel." Dickerson is brilliant, and so is his prose.

-

Hunter S. Thompson, Screwjack. This is the book Carlos Castaneda would have written if he'd admitted he was writing fiction. You feel the intoxication, and you believe it.

- Herman Melville, Moby Dick. This is one of those books that everyone knows and nearly nobody reads. It is long, and full of words. Lots and lots of words. But wow. It is one of those rare books that gives me the sense that every sentence was the child of long and serious reflection. Reading this was like taking a really good class. Naturally, I bought myself a "What Would Queequeg Do?" t-shirt to mark this milestone in my life. You can get yours here.

- Nathaniel Hawthorne, Mosses From An Old Manse. And this is like Melville. You read it because at the end, you discover that what seemed to be a simple story about a simple thing makes you understand your world a lot better.

- John Steinbeck, The Moon Is Down. I love Steinbeck, so I bought this book not knowing a thing about it. Turns out Steinbeck wrote it as a propaganda piece. He wanted to give a picture of what it would look like to live in, say, Norway or Denmark under Nazi rule, and how that occupation could lead to resistance. What I love about Steinbeck is, more than anything, his desire to portray people with sympathy. The Nazis in his book are real people, believable, and even likeable. I wish we had more people able to portray our contemporary enemies with such sympathy. If we could do so, we could love them better, and I think we could better understand how to resist them. As a bonus, towards the end of the novel there is a prolonged reflection on the meaning of Plato's Apology of Socrates.

- Patrick Hicks, The Commandant of Lubizec. (Another disclosure: Hicks is also my friend.) I was pretty sure I'd read all I needed to read about the Holocaust. I grew up with survivors. I've read all the usual books, I teach several in my classes. I didn't want to hear any more. But Hicks has done something truly remarkable in this fictionalized account of Operation Reinhard. In fact, what he's done is similar to what Steinbeck does: he has written about people with real sympathy and insight. It's a hard read because he spares us nothing, but that's precisely what makes it such a good read. Here's a short video about the book:

∞

Good Education Should Lead To Good Questions

"If we treat the contemplation of the best life as a luxury we cannot

afford, seemingly urgent matters will crowd out the truly important

ones."

[....]

"If the aim of education is to gain money and power, where can we turn for help in knowing what to do with that money and power? Only a disordered mind thinks that these are ends in themselves. Socrates offers us the cautionary tale of the athlete-physician Herodicus, who wins fame and money through his athletic prowess and medicine, then proceeds to spend all his wealth trying to preserve his youth. This is what we mean by a disordered mind. He has been trained in the STEM fields of his time, and his training gains him great wealth, but it leaves him foolish enough to spend it all on something he can never buy."

[....]

"If the aim of education is to gain money and power, where can we turn for help in knowing what to do with that money and power? Only a disordered mind thinks that these are ends in themselves. Socrates offers us the cautionary tale of the athlete-physician Herodicus, who wins fame and money through his athletic prowess and medicine, then proceeds to spend all his wealth trying to preserve his youth. This is what we mean by a disordered mind. He has been trained in the STEM fields of his time, and his training gains him great wealth, but it leaves him foolish enough to spend it all on something he can never buy."

From my latest article, co-authored with John Kaag, in The Chronicle of Higher Education. Read it all here.

∞

Socratic Pragmatism: On Our Attitude Towards Inquiry

"I do not insist that my argument is right in all other respects, but I would contend at all costs in both word and deed as far as I could that we will be better men, braver and less idle, if we believe that one must search for the things one does not know, rather than if we believe that it is not possible to find out what we do not know and that we must not look for it."

Socrates, in Plato’s Meno, 86b-. G.M.A. Grube, trans.

∞

More Books Worth Reading

One of the great pleasures of being a teacher is reading. To do my job well, I have to read. If I don't read a lot, I won't keep up with my field and I'll be a poorer teacher. Fortunately, I like reading.

Even so, one of the great surprises of being a teacher is that, at the end of a long day of work reading, I like to unwind with a good book. Go figure.

The last few months have brought me a surfeit of good books to unwind with. Here are some of the recent books I've enjoyed:

Even so, one of the great surprises of being a teacher is that, at the end of a long day of work reading, I like to unwind with a good book. Go figure.

The last few months have brought me a surfeit of good books to unwind with. Here are some of the recent books I've enjoyed:

∞

College Athletics: Cui Bono?

This Strange Marriage of Athletics and Academics

This week I've been considering the place of sports on American university and college campuses. (See here and here for the other pieces I've written on this this week.)

If you grow up here, it doesn't seem at all strange, because it's simply how things are. But a little reflection suggests that the juxtaposition of academics and athletics is a little strange.

I say it is "a little" strange because throughout the ages thoughtful people have said that the two complement each other. Plato's Republic discusses the relationship between gymnastics for the body and philosophy for the mind, for instance. Of course, Plato, famous for his irony, is never wholly straightforward, and the target he is aiming at is probably something else, but the characters in his dialogue act as though bodily exercise and mental exercise are related.

Walking, Playing, and Thinking

One of Socrates' other students, Xenophon, wrote in his Cynegetica that the best education comes through learning to hunt, and that book-learning should only come after a boy has learned the art of coursing with hounds, and practiced it in the country. And there are many others who tell us that moving our bodies and learning go together: Maria Montessori reminds us that the work of children is play. Philosophers as diverse as Aristotle, Nietzsche, C.S. Lewis, Henry Thoreau and Charles S. Peirce tell us that walking and thinking are natural companions.

So the strangeness of the marriage of learning and playing is not the hypothesis that the body and the mind work both need exercise. The strangeness is the way we pursue - or, just as often, fail to pursue - that hypothesis. We are told that movement helps us think, and that playing team sports teaches us virtue. If all that is true, then why do we not encourage all students to play sports?

The Irony: We Do Not Practice As We Preach

Speaking of irony, consider this: What we claim and what we actually do are at odds with one another. We say sports are good for everyone, then we expect coaches to eliminate all but the best athletes from their instruction. Rather than advertising our schools as places where students can get an excellent physical education we expect our coaches to travel far and wide to recruit only the best athletes, i.e. those who need the least instruction and who are most likely to win competitions. It is fairly obvious that, rather than using athletics as a means of inculcating virtue and fostering better thinking, we use athletics to gain honor through victories.

And of course, this is obvious to us. We want to win games because winning is a form of advertising. For good or ill, we accept the fact that high school students will often choose our school in order to participate in the glory of competitions won. But we continue to give the other justifications for participation in athletics, perhaps because we perceive that it would be crass to come right out and say "Come to our college and bask in the glory won by others. It will thrill you, and it might help your job prospects," or "We hope that the victories of our athletes will help us to raise money from people who won't give unless we are winning games."

I don't want to be cynical about this. As I have suggested above and said directly in my previous posts, I'm in favor of athleticism. What troubles me about it is the way that certain college sports become increasingly professionalized. Why, after all, are student athletes considering unionizing? That's something employees do, not students.

Let Everyone Learn To Play

My conclusion is not to push for the elimination of college athletics, but for athletics to be brought more into line with the best reasons for preserving it. If playful exercise makes us better people and better students, then let's urge more students to play. Let's give less attention to inter-collegiate competition and more attention to teaching lifetime sports that will allow our alumni to enjoy the benefits of physical activity for the remainder of their lives. Let's teach poorer students to play golf so that when they enter the business world they aren't at a disadvantage when deals are made on the fairway. Let's teach everyone to swim. Let's take all our students on walks - serious walks, cross-country walks. Let's teach them what Thoreau calls the art of sauntering.

Playful activity takes many forms. We should resist the temptation to think of it as the pursuit of a ball. Swimming, hiking, rock climbing, Tai Chi, dance, yoga, and numerous other activities have the same moral and intellectual benefits as team sports. There should be as many opportunities for vigorous play as there are bodies.

Some of my friends have balked at this, understandably. Not all of us are athletic, or at least not all of us feel athletic. But I think a good deal of this is because many of us learned about athletics in a victory-oriented environment. That environment fosters a narrow and shallow view of the active human life. We may not all be quarterbacks, point guards, shortstops, or strikers, but all of us can be active within the limits of the bodies we have been given. If activity is good for us, then we should treat it as good for all of us. Play should not be limited to the activity of a few for the thrill of the inactive many. Play should be, as Peirce said, "a lively exercise of our powers," whatever those powers may be. And it should be a delight.

This week I've been considering the place of sports on American university and college campuses. (See here and here for the other pieces I've written on this this week.)

If you grow up here, it doesn't seem at all strange, because it's simply how things are. But a little reflection suggests that the juxtaposition of academics and athletics is a little strange.

I say it is "a little" strange because throughout the ages thoughtful people have said that the two complement each other. Plato's Republic discusses the relationship between gymnastics for the body and philosophy for the mind, for instance. Of course, Plato, famous for his irony, is never wholly straightforward, and the target he is aiming at is probably something else, but the characters in his dialogue act as though bodily exercise and mental exercise are related.

Walking, Playing, and Thinking

One of Socrates' other students, Xenophon, wrote in his Cynegetica that the best education comes through learning to hunt, and that book-learning should only come after a boy has learned the art of coursing with hounds, and practiced it in the country. And there are many others who tell us that moving our bodies and learning go together: Maria Montessori reminds us that the work of children is play. Philosophers as diverse as Aristotle, Nietzsche, C.S. Lewis, Henry Thoreau and Charles S. Peirce tell us that walking and thinking are natural companions.

So the strangeness of the marriage of learning and playing is not the hypothesis that the body and the mind work both need exercise. The strangeness is the way we pursue - or, just as often, fail to pursue - that hypothesis. We are told that movement helps us think, and that playing team sports teaches us virtue. If all that is true, then why do we not encourage all students to play sports?

The Irony: We Do Not Practice As We Preach

Speaking of irony, consider this: What we claim and what we actually do are at odds with one another. We say sports are good for everyone, then we expect coaches to eliminate all but the best athletes from their instruction. Rather than advertising our schools as places where students can get an excellent physical education we expect our coaches to travel far and wide to recruit only the best athletes, i.e. those who need the least instruction and who are most likely to win competitions. It is fairly obvious that, rather than using athletics as a means of inculcating virtue and fostering better thinking, we use athletics to gain honor through victories.

And of course, this is obvious to us. We want to win games because winning is a form of advertising. For good or ill, we accept the fact that high school students will often choose our school in order to participate in the glory of competitions won. But we continue to give the other justifications for participation in athletics, perhaps because we perceive that it would be crass to come right out and say "Come to our college and bask in the glory won by others. It will thrill you, and it might help your job prospects," or "We hope that the victories of our athletes will help us to raise money from people who won't give unless we are winning games."

I don't want to be cynical about this. As I have suggested above and said directly in my previous posts, I'm in favor of athleticism. What troubles me about it is the way that certain college sports become increasingly professionalized. Why, after all, are student athletes considering unionizing? That's something employees do, not students.

Let Everyone Learn To Play

My conclusion is not to push for the elimination of college athletics, but for athletics to be brought more into line with the best reasons for preserving it. If playful exercise makes us better people and better students, then let's urge more students to play. Let's give less attention to inter-collegiate competition and more attention to teaching lifetime sports that will allow our alumni to enjoy the benefits of physical activity for the remainder of their lives. Let's teach poorer students to play golf so that when they enter the business world they aren't at a disadvantage when deals are made on the fairway. Let's teach everyone to swim. Let's take all our students on walks - serious walks, cross-country walks. Let's teach them what Thoreau calls the art of sauntering.

Playful activity takes many forms. We should resist the temptation to think of it as the pursuit of a ball. Swimming, hiking, rock climbing, Tai Chi, dance, yoga, and numerous other activities have the same moral and intellectual benefits as team sports. There should be as many opportunities for vigorous play as there are bodies.

Some of my friends have balked at this, understandably. Not all of us are athletic, or at least not all of us feel athletic. But I think a good deal of this is because many of us learned about athletics in a victory-oriented environment. That environment fosters a narrow and shallow view of the active human life. We may not all be quarterbacks, point guards, shortstops, or strikers, but all of us can be active within the limits of the bodies we have been given. If activity is good for us, then we should treat it as good for all of us. Play should not be limited to the activity of a few for the thrill of the inactive many. Play should be, as Peirce said, "a lively exercise of our powers," whatever those powers may be. And it should be a delight.

∞

Three Words About Writing: Plato, Emerson, Bugbee

Last weekend I was at a small writing conference in Vermont, where I was asked to give a meditation on writing with a love of wisdom. Although I'm a philosophy professor, I'm not sure I have a bead on loving wisdom yet.

(To paraphrase Thoreau, there are nowadays plenty of philosophy professors, but not so many lovers of wisdom.)

Instead, I offered a reflection on three ideas that matter for me as I write. Here are three that I keep coming back to:

First, a word from Plato: "Follow the argument wherever it leads." And try to find good interlocutors. If you surround yourself with people who say "yes" to everything you say, your writing and your thinking will both atrophy. If the trail leads uphill, it's no good to stay on the level path. Plato seems to have used writing as a way of sketching out how one might begin to solve problems. He didn't give answers so much as good questions. His dialogues survive because they are such good invitations for us to try to work out the solutions ourselves.

Second, Emerson: Your journals are your savings accounts. Your life is the way you earn deposits. "If it were only for a vocabulary the scholar would be covetous of action," he wrote. "Life is our dictionary." Without action, there is no experience; and without experience, the writer's vocabulary becomes continually narrower. Emerson wrote in fragments - very short essays, or sentences - in his journals, and when he sat down to write his essays and lectures, he found those fragments to be a rich vein of inspiration and even of finished work.

Finally, Bugbee: "Get it down." Write forward; don't edit too much. Keep writing, and as much as possible, write the way it comes. Attend to experience as it is given, without trying too hard to color it or shape it. Practice seeing, and seeing honestly, and write what you see.

This isn't by any means a whole course in writing, but it is a place to start. And often, that's what writers need: to start.

Then keep writing.

(To paraphrase Thoreau, there are nowadays plenty of philosophy professors, but not so many lovers of wisdom.)

Instead, I offered a reflection on three ideas that matter for me as I write. Here are three that I keep coming back to:

First, a word from Plato: "Follow the argument wherever it leads." And try to find good interlocutors. If you surround yourself with people who say "yes" to everything you say, your writing and your thinking will both atrophy. If the trail leads uphill, it's no good to stay on the level path. Plato seems to have used writing as a way of sketching out how one might begin to solve problems. He didn't give answers so much as good questions. His dialogues survive because they are such good invitations for us to try to work out the solutions ourselves.

Second, Emerson: Your journals are your savings accounts. Your life is the way you earn deposits. "If it were only for a vocabulary the scholar would be covetous of action," he wrote. "Life is our dictionary." Without action, there is no experience; and without experience, the writer's vocabulary becomes continually narrower. Emerson wrote in fragments - very short essays, or sentences - in his journals, and when he sat down to write his essays and lectures, he found those fragments to be a rich vein of inspiration and even of finished work.

Finally, Bugbee: "Get it down." Write forward; don't edit too much. Keep writing, and as much as possible, write the way it comes. Attend to experience as it is given, without trying too hard to color it or shape it. Practice seeing, and seeing honestly, and write what you see.

This isn't by any means a whole course in writing, but it is a place to start. And often, that's what writers need: to start.

Then keep writing.

∞

Finding One's Way: Three Questions About Vocation

My students often ask me, "What should I do with my life after I graduate?"

The simple answer I usually give is this: you should pursue your vocation.

In answering that way, I hope to encourage students not to accept others' stories about how their lives should go, and to begin to give them some tools for answering their own question.

My reason for caution is that the word "vocation" is a tricky one. It has tendrils that grow in many directions, and some of them don't need much fertilizer before they reach into some messy metaphysical and ethical questions.

There's an important lesson in all those stories about magic that have been handed down through the ages: words have real power to change the world and to swerve the direction of others' actions. Which means they should be handled with care. "Vocation" is one of the strong words. It's got a kind of magic to it because it has the power to enchant our lives by drawing a lot of ideas together into one place, and by drawing some long arrows leading towards and away from the place where you stand right now. Its root, the Latin word vocatio, means "calling." This is what I mean by the "tendrils" and the messy metaphysics they can grow into: if you're called, that might imply a caller, which might imply some strong obligations.

Here are some suggestions for how to handle the idea of vocation with care:

First, don't tell other people what their vocation must be. Imposing strong narratives on others' lives is what we do when we pretend to be God. I don't recommend trying to play that role. Read some Milton before you do, anyway.

Second, no matter how strong your sense of your own calling, remember that we see as in a glass, darkly. You can't judge a voice except with your own ears, so remember the limitations of your hearing.

Third, and along those same lines, don't make rash decisions about the last step of your journey; look instead to the next step. This means having some humility, and a lot of patience with yourself and with your own life. It means not knowing how the story of your life will unfold, but reading it - and writing it - one page at a time.

With those caveats in mind, here are three questions that I offer students who are trying to figure out what their calling may be. I recommend taking the time to consider them thoughtfully. Write your answers down, and after a while, ask trustworthy friends who know you and love you if they agree with your answers. As you consider these questions, don't think about jobs and careers, lest that limit your answers. The aim in asking each of these questions is this: to know yourself better.

First, what are you good at? What are your skills and your strengths? Don't just think about the things you enjoy doing here; include all your gifts and talents.

Second, what do you love to do? Don't just think about what you're good at, but include those things you love but haven't any talent for.

Third, what do you want to accomplish? How would you like the world to be changed when you are done with it? How would you like to be known? What do you most want to do, or be? What would you write in your autobiography?

Do any patterns appear? As you answer these questions honestly, do you discover anything about yourself that you didn't see clearly before? Answering these questions won't sort everything out for you, and I know I can't tell you what your calling is. But I do think that getting to know yourself, your loves, your talents, and your aspirations can help you to avoid simply doing what others want you to do. And they just might shed some light on the path ahead.

The simple answer I usually give is this: you should pursue your vocation.

In answering that way, I hope to encourage students not to accept others' stories about how their lives should go, and to begin to give them some tools for answering their own question.

My reason for caution is that the word "vocation" is a tricky one. It has tendrils that grow in many directions, and some of them don't need much fertilizer before they reach into some messy metaphysical and ethical questions.

There's an important lesson in all those stories about magic that have been handed down through the ages: words have real power to change the world and to swerve the direction of others' actions. Which means they should be handled with care. "Vocation" is one of the strong words. It's got a kind of magic to it because it has the power to enchant our lives by drawing a lot of ideas together into one place, and by drawing some long arrows leading towards and away from the place where you stand right now. Its root, the Latin word vocatio, means "calling." This is what I mean by the "tendrils" and the messy metaphysics they can grow into: if you're called, that might imply a caller, which might imply some strong obligations.

Here are some suggestions for how to handle the idea of vocation with care:

First, don't tell other people what their vocation must be. Imposing strong narratives on others' lives is what we do when we pretend to be God. I don't recommend trying to play that role. Read some Milton before you do, anyway.

Second, no matter how strong your sense of your own calling, remember that we see as in a glass, darkly. You can't judge a voice except with your own ears, so remember the limitations of your hearing.

Third, and along those same lines, don't make rash decisions about the last step of your journey; look instead to the next step. This means having some humility, and a lot of patience with yourself and with your own life. It means not knowing how the story of your life will unfold, but reading it - and writing it - one page at a time.

With those caveats in mind, here are three questions that I offer students who are trying to figure out what their calling may be. I recommend taking the time to consider them thoughtfully. Write your answers down, and after a while, ask trustworthy friends who know you and love you if they agree with your answers. As you consider these questions, don't think about jobs and careers, lest that limit your answers. The aim in asking each of these questions is this: to know yourself better.

First, what are you good at? What are your skills and your strengths? Don't just think about the things you enjoy doing here; include all your gifts and talents.

Second, what do you love to do? Don't just think about what you're good at, but include those things you love but haven't any talent for.

Third, what do you want to accomplish? How would you like the world to be changed when you are done with it? How would you like to be known? What do you most want to do, or be? What would you write in your autobiography?

Do any patterns appear? As you answer these questions honestly, do you discover anything about yourself that you didn't see clearly before? Answering these questions won't sort everything out for you, and I know I can't tell you what your calling is. But I do think that getting to know yourself, your loves, your talents, and your aspirations can help you to avoid simply doing what others want you to do. And they just might shed some light on the path ahead.

∞

"I Know That I Don't Know"?

If you stroll through the Plaka tourist district in Athens, you'll have ample opportunities to buy t-shirts and other items with the slogan "en oida oti ouden oida," most of which will attribute this saying to Socrates. It means "I know this one thing: that I know nothing."

Of course, it is a little silly and possibly self-contradictory, since knowing one thing means knowing something, while knowing nothing precludes knowing something.

Still, if Socrates said it, it's worth repeating, right? (For kicks, Google it and see how many times it is quoted authoritatively.)

But I wonder if Socrates ever said it at all.

Yes, I know that we don't know exactly what Socrates said. Socrates left us no writings, and as for transcriptions of his conversations, we have only three first-hand sources to rely on: those of Plato and Xenophon his students, and of Aristophanes his ostensible rival. It seems likely that Aristophanes did not attempt to represent Socrates accurately, nor as a philosopher. Plato may well have invented much of Socrates' dialogue as well, but he also had a stake in continuing and defending the philosophical work of Socrates in Athens.

For this reason, when philosophers refer to Socrates, we are usually referring to the Socrates found in Plato's rather extensive writings.

So did Plato's Socrates ever say "en oida oti ouden oida"? It appears not.

The closest thing I've found is a passage in Plato's Apology of Socrates, where Socrates says something that should really be translated as something like this: I do not claim to know those things that I do not know.

This is not only more reasonable, it's also good advice: don't pretend to know what you don't know and you'll avoid a lot of trouble.

It's important for another reason, though. The "en oida oti ouden oida" quote seems to be something of a staple of frosh philosophy texts and classes.

The danger here is that we will present an ancient philosopher (two of them, in this case) as though he were fairly foolish; and as a result, we will not take ancient philosophy seriously.

All it should take to cure this is a quick look at the Greek text of any of Plato's dialogues. The Phaedo, for instance, bears a slow and careful read in Greek, since no translation I've found captures all the wordplay. And as Peirce pointed out, when one reads the Greek, one discovers something else that the translators often veil from our sight: Plato's Socrates uses the language of syllogism in a way that shows that he was doing Aristotelian logic before Aristotle was.

By relying on hearsay rather than on engagement with the primary texts, we close off a path of inquiry into a whole set of ancient philosophical texts. "Doesn't their being ancient mean that they are exhausted?" you may ask. Old trees, it seems to me, may still bear rich fruit. And just as we find that old caves sometimes have rich troves of ancient unread texts, what else might we find if we take the time to read the ancients closely?

Of course, it is a little silly and possibly self-contradictory, since knowing one thing means knowing something, while knowing nothing precludes knowing something.

Still, if Socrates said it, it's worth repeating, right? (For kicks, Google it and see how many times it is quoted authoritatively.)

But I wonder if Socrates ever said it at all.

Yes, I know that we don't know exactly what Socrates said. Socrates left us no writings, and as for transcriptions of his conversations, we have only three first-hand sources to rely on: those of Plato and Xenophon his students, and of Aristophanes his ostensible rival. It seems likely that Aristophanes did not attempt to represent Socrates accurately, nor as a philosopher. Plato may well have invented much of Socrates' dialogue as well, but he also had a stake in continuing and defending the philosophical work of Socrates in Athens.

For this reason, when philosophers refer to Socrates, we are usually referring to the Socrates found in Plato's rather extensive writings.

So did Plato's Socrates ever say "en oida oti ouden oida"? It appears not.

The closest thing I've found is a passage in Plato's Apology of Socrates, where Socrates says something that should really be translated as something like this: I do not claim to know those things that I do not know.

This is not only more reasonable, it's also good advice: don't pretend to know what you don't know and you'll avoid a lot of trouble.

It's important for another reason, though. The "en oida oti ouden oida" quote seems to be something of a staple of frosh philosophy texts and classes.

The danger here is that we will present an ancient philosopher (two of them, in this case) as though he were fairly foolish; and as a result, we will not take ancient philosophy seriously.

All it should take to cure this is a quick look at the Greek text of any of Plato's dialogues. The Phaedo, for instance, bears a slow and careful read in Greek, since no translation I've found captures all the wordplay. And as Peirce pointed out, when one reads the Greek, one discovers something else that the translators often veil from our sight: Plato's Socrates uses the language of syllogism in a way that shows that he was doing Aristotelian logic before Aristotle was.

By relying on hearsay rather than on engagement with the primary texts, we close off a path of inquiry into a whole set of ancient philosophical texts. "Doesn't their being ancient mean that they are exhausted?" you may ask. Old trees, it seems to me, may still bear rich fruit. And just as we find that old caves sometimes have rich troves of ancient unread texts, what else might we find if we take the time to read the ancients closely?

∞

Socrates and the Trees

It's always dangerous to assume one knows what Plato thinks, since Plato goes out of his way not to tell us what he thinks. Nevertheless, inasmuch as Socrates is his mouthpiece, here is one place where I think Socrates is mistaken. Socrates, speaking to Phaedrus, says, "I'm a lover of learning, and trees and open country won't teach me anything, whereas men in the town do." (230d)

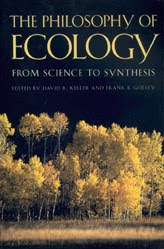

I disagree with what Socrates says here, and it is an unfortunate fact of history that many Platonists have taken a similar position to this one. I just read this line in an otherwise very good book, David Keller and Frank Golley's The Philosophy of Ecology: From Science To Synthesis.

It's a fine collection of key articles in environmental philosophy. In the introduction, however, they contrast Socrates with Thoreau - something Thoreau himself did - and make Thoreau out to be the one more interested in trees. Thoreau was interested in trees, especially at the end of his life, but that does not make the comparison apt.

The irony of this line is that it comes from a dialogue in which Socrates continues to point out to his interlocutor just how much one can learn from a close observation of nature. He repeatedly draws attention to the trees, the water, and the cicadas. Socrates and Plato are not known as fathers of empiricism, but the view that their heads are so far in the Clouds that they cannot see the well they're about to step into has occupied too much of our attention. We would do better to notice that Socrates pays attention to the trees. We would do better still to pay some attention to the trees ourselves.

I disagree with what Socrates says here, and it is an unfortunate fact of history that many Platonists have taken a similar position to this one. I just read this line in an otherwise very good book, David Keller and Frank Golley's The Philosophy of Ecology: From Science To Synthesis.

It's a fine collection of key articles in environmental philosophy. In the introduction, however, they contrast Socrates with Thoreau - something Thoreau himself did - and make Thoreau out to be the one more interested in trees. Thoreau was interested in trees, especially at the end of his life, but that does not make the comparison apt.

The irony of this line is that it comes from a dialogue in which Socrates continues to point out to his interlocutor just how much one can learn from a close observation of nature. He repeatedly draws attention to the trees, the water, and the cicadas. Socrates and Plato are not known as fathers of empiricism, but the view that their heads are so far in the Clouds that they cannot see the well they're about to step into has occupied too much of our attention. We would do better to notice that Socrates pays attention to the trees. We would do better still to pay some attention to the trees ourselves.