stone

∞

The Trace I Left Behind

This summer I spent several weeks in and around Lake Clark National Park doing research on trout, salmon, and char.

Sometimes I get quizzical looks when I say that I, a philosophy and classics professor, am researching fish. Let me explain.

I teach environmental philosophy and a range of classes in what I call "environmental humanities." These include courses in environmental ethics, nature writing, philosophy of nature, and even a course on environmental law and policy for first-year undergraduates, as an introduction to being a university student.

I also teach courses in field ecology, including a monthlong course in tropical ecology in Guatemala and Belize. I teach in Greece over my spring break, and this year we will be looking at the expansion of fish farms in the Mediterranean and how fishing has changed there over the last six thousand years.

Closer to home, I teach and practice what Norwegians call friluftsliv, or life in the free air. Whenever possible, I teach outdoors. Most years, I take my ancient philosophy students camping in the Badlands National Park to watch the Orionid meteor shower while we lie on sleeping bags under the stars.

In all of this, my aim is to make sure that nature is not an abstraction to my students, nor to me. I want to know the places the fish live, the grasslands the bison roam, the forests where the jaguar and the ocelot hunt, the tundra rivers where the Dolly Varden chase the salmon under the watchful gaze of the bears.

In other words, my aim is to stay in contact with wildness, and to do so in a way that allows me to take something valuable home: intimate knowledge. I am not a scientist, so I don't bring samples back to a laboratory. I do bring home photographs, and I do spend a lot of time making observations of the places I work, so that I can bring home notebooks full of writing to share with my students. And of course, I write books and articles to share with others.

This summer, I was sorely tempted to bring something else home from Lake Clark: a tiny fossil. I had chartered a float plane to take me to a fairly remote lake, and there my fellow researchers and I walked the shore to the mouth of a stream full of spawning salmon and rainbow trout.

As I often do, I sat down on the gravel and started to turn over rocks to see what invertebrates were living there. The salmon are bright red and eye-catching, but the bugs and spiders tell an important part of the story of a place, as Kurt Fausch has written about in his recent book, For The Love Of Rivers. Who was it - J.B.S. Haldane, perhaps? - who quipped that God has "an inordinate fondness for beetles." The world is full of wonderful, tiny lives that are easy to overlook.

I don't try to bring beetles home, but one insect tempted me this summer. Really, it was just a trace of an insect, just the trace of its wings, in fact. I can't even tell you what insect it was. All I can tell you is that somewhere near that river, probably millions of years ago, something like a dragonfly died in the mud, and the river graced its delicate wings with the cerement of silt. That silt took the form of the wings, those wings left a fingerprint - a wingprint - on the earth. And this summer, I found that print, that delicate, wonderful trace.

While my son and my friend and our pilot walked, I sat with that stone in my hand and thought about pocketing it. Here I was in the wilderness, and no one would know. It's one tiny stone in the largest state in the union; who would miss it?

Ah, but it is one tiny stone that does not belong to me. It is one tiny stone in a vast wilderness that belongs to all of us, and to all who will come after us. It is one tiny piece of rock with an incomplete fossil of a little odonata. The river there has held it and cared for it since time immemorial.

Now I am back in South Dakota, but a tiny trace of my heart remains along the strand of that stream in Alaska. It lies there, wrapped around that delicate trace of insect wing, and I will never find it again in that vast wilderness.

But perhaps someone else will. Until then, perhaps it is best not to let Midas' longings turn our hearts to stone too soon. Let's walk the shores together, I will continue to say to my students. And let's bring something intangible home in our memories. And let's do the hard work of leaving behind the beautiful, delicate traces that wildness has safeguarded for so many, many years.

Sometimes I get quizzical looks when I say that I, a philosophy and classics professor, am researching fish. Let me explain.

I teach environmental philosophy and a range of classes in what I call "environmental humanities." These include courses in environmental ethics, nature writing, philosophy of nature, and even a course on environmental law and policy for first-year undergraduates, as an introduction to being a university student.

I also teach courses in field ecology, including a monthlong course in tropical ecology in Guatemala and Belize. I teach in Greece over my spring break, and this year we will be looking at the expansion of fish farms in the Mediterranean and how fishing has changed there over the last six thousand years.

Closer to home, I teach and practice what Norwegians call friluftsliv, or life in the free air. Whenever possible, I teach outdoors. Most years, I take my ancient philosophy students camping in the Badlands National Park to watch the Orionid meteor shower while we lie on sleeping bags under the stars.

In all of this, my aim is to make sure that nature is not an abstraction to my students, nor to me. I want to know the places the fish live, the grasslands the bison roam, the forests where the jaguar and the ocelot hunt, the tundra rivers where the Dolly Varden chase the salmon under the watchful gaze of the bears.

In other words, my aim is to stay in contact with wildness, and to do so in a way that allows me to take something valuable home: intimate knowledge. I am not a scientist, so I don't bring samples back to a laboratory. I do bring home photographs, and I do spend a lot of time making observations of the places I work, so that I can bring home notebooks full of writing to share with my students. And of course, I write books and articles to share with others.

This summer, I was sorely tempted to bring something else home from Lake Clark: a tiny fossil. I had chartered a float plane to take me to a fairly remote lake, and there my fellow researchers and I walked the shore to the mouth of a stream full of spawning salmon and rainbow trout.

|

| Salmon preparing to spawn |

As I often do, I sat down on the gravel and started to turn over rocks to see what invertebrates were living there. The salmon are bright red and eye-catching, but the bugs and spiders tell an important part of the story of a place, as Kurt Fausch has written about in his recent book, For The Love Of Rivers. Who was it - J.B.S. Haldane, perhaps? - who quipped that God has "an inordinate fondness for beetles." The world is full of wonderful, tiny lives that are easy to overlook.

I don't try to bring beetles home, but one insect tempted me this summer. Really, it was just a trace of an insect, just the trace of its wings, in fact. I can't even tell you what insect it was. All I can tell you is that somewhere near that river, probably millions of years ago, something like a dragonfly died in the mud, and the river graced its delicate wings with the cerement of silt. That silt took the form of the wings, those wings left a fingerprint - a wingprint - on the earth. And this summer, I found that print, that delicate, wonderful trace.

|

| Fossilized trace of an insect's wing |

While my son and my friend and our pilot walked, I sat with that stone in my hand and thought about pocketing it. Here I was in the wilderness, and no one would know. It's one tiny stone in the largest state in the union; who would miss it?

Ah, but it is one tiny stone that does not belong to me. It is one tiny stone in a vast wilderness that belongs to all of us, and to all who will come after us. It is one tiny piece of rock with an incomplete fossil of a little odonata. The river there has held it and cared for it since time immemorial.

Now I am back in South Dakota, but a tiny trace of my heart remains along the strand of that stream in Alaska. It lies there, wrapped around that delicate trace of insect wing, and I will never find it again in that vast wilderness.

But perhaps someone else will. Until then, perhaps it is best not to let Midas' longings turn our hearts to stone too soon. Let's walk the shores together, I will continue to say to my students. And let's bring something intangible home in our memories. And let's do the hard work of leaving behind the beautiful, delicate traces that wildness has safeguarded for so many, many years.

∞

Gifts From My Father

My father spent his career as an engineer working for IBM and NASA. Growing up with an engineer is an education in itself. As a boy, I felt like whenever I was with my father, I was learning new things. We'd go out for pizza and he'd write chemical equations on napkins. We'd go to the Ashokan Reservoir and he'd tell me the history of the valley that was flooded so that New York could get water, and then he'd tell me how they engineered the pipeline that carried the water to the city.

Often he was at his desk or his workbench, and I didn't want to interrupt him when he was working on problem-solving, but I'd try to spend time in his office or workroom until I made too much noise and was asked to move on to other exploits. I'd stare at his shelves, heavy with books and tools, and full of things he had picked up in his travels. He had a small, round stone that he had found somewhere, that had been shaped as a toy by our Algonquin ancestors. He had musical instruments and geometric shapes made of plastic and wire, and books on how to learn Russian or how to understand religion. On his workbench there was an oscilloscope that he'd sometimes use, and I loved that machine's interpretation of the data it received. My father's mind is a small liberal arts college unto itself, and his curiosity about the world seems to know no limits.

Recently I was going through some boxes of things that have moved across the country with me many times. I am an anti-hoarder, someone who prefers to give things away rather than store them forever. But some things are hard to part with, especially when the memories associated with them are so strong.

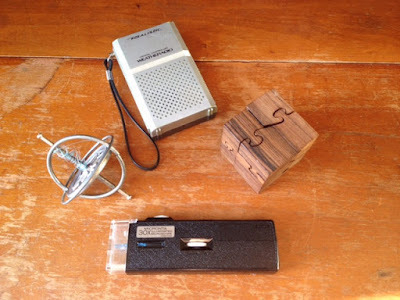

Here's a snapshot of a few of the things I hang onto precisely because they remind me of Dad. The gyroscope and wooden puzzle were gifts he brought me when I was a small boy. I think he got them on business trips. I've kept them both because they bring me wonder and delight, and because I like to use them to teach children. The weather radio is probably silly, and I don't use it any more, but it reminds me both of Dad's constant interest in solving problems before they are crises, and of his lifelong interest in electrical engineering. He built a computer in his fraternity house back before most people knew what computers were. He would take apart radios so he could put them back together and understand how they worked.

I never picked up his gift for electrical engineering, but I've got his curiosity about how things work, which I tend to apply more towards ecology than technology. For me, technology and ecology come together in some important ways, nonetheless. This pocket microscope he gave me has been with me for thirty years or more, and I like to think of it as a seed. I've often been tempted to give it away, but instead I have held onto it, and every time I think of giving it away I buy more of them and give them to teachers. Each year I teach for a month in Guatemala, and while I am there I look for teachers in local schools and give them boxes of microscopes and other hand lenses.

I am reminded that much of the history of science (Dad's field ) and of philosophy (my field) have grown with advances in optics. When scientists get better lenses and lasers and satellites, knowledge tends to grow rapidly.

The same is true for children: give them a hand lens, or an insect viewer, or a microscope with some prepared slides, and the world will suddenly become new to them. Dad planted that seed in me long ago. Now I carry a hand lens with me almost everywhere I go. I suppose the whole of my career is a reflection of the things that delight Dad and provoke his curiosity; most of them delight me and make me curious, too. And just as Dad passed on his curiosity to me, now it is my turn to pass it on to others.

The same is true for children: give them a hand lens, or an insect viewer, or a microscope with some prepared slides, and the world will suddenly become new to them. Dad planted that seed in me long ago. Now I carry a hand lens with me almost everywhere I go. I suppose the whole of my career is a reflection of the things that delight Dad and provoke his curiosity; most of them delight me and make me curious, too. And just as Dad passed on his curiosity to me, now it is my turn to pass it on to others.

∞

Free Stone

One spring after heavy rains had come and gone, my father and I walked the banks of the Sawkill Creek. It was newly scrubbed by floodwaters that had gouged its banks, sweeping away trees, glacial deposit boulders, and even a few buildings as the Catskills shed the rainfall and shot it down to the Hudson.

The memory of that short walk remains one of the strongest from my childhood. The river had cut new banks, and had changed its own course. We walked along the round gravel banks and gazed up at the undercut roots of massive oaks and pines. We saw the bones of the earth laid bare by the river's irresistible blade. The river had cut itself a new bed. Everything in its path was destroyed; everything in its path was made new.

Since then I have walked hundreds of miles along - and often in - deep, clear waters over cobbled riverbeds. The sound of the water is the music of my soul, high sprinkled notes of splashing water and bass tones of massive stones rocking back and forth in the current. Walking in freestone streams makes me forget my worries, forget time itself.

The memory of that short walk remains one of the strongest from my childhood. The river had cut new banks, and had changed its own course. We walked along the round gravel banks and gazed up at the undercut roots of massive oaks and pines. We saw the bones of the earth laid bare by the river's irresistible blade. The river had cut itself a new bed. Everything in its path was destroyed; everything in its path was made new.

|

| Polished by the river. |

Since then I have walked hundreds of miles along - and often in - deep, clear waters over cobbled riverbeds. The sound of the water is the music of my soul, high sprinkled notes of splashing water and bass tones of massive stones rocking back and forth in the current. Walking in freestone streams makes me forget my worries, forget time itself.