water

- This short documentary about what Urban Rivers is doing with floating gardens in Chicago. They’ve made some habitat for one of the hardier species of unionid mussels native to the river. Did you know that some mature mussels can filter 20 gallons of water a day? Here in Sioux Falls I want to restore our river. Organizations like Urban Rivers can be a good inspiration for what we might do here. If this appeals to you, I suggest making a donation to Friends of the Big Sioux River. They do a lot of good work on a tiny budget.

- David Strayer’s Freshwater Mussel Ecology: A Multifactor Approach to Distribution and Abundance Strayer recognizes that ecologists often explain distribution in terms of general factors but without much quantification and precision. His book attempts to describe “a literal, quantitative prediction of the distribution and abundance of individual species.” (p. 6) Mussels are easy to overlook and often hard to find. They can be found in water that is still or fast-moving, clear or murky, shallow or deep. They might be embedded in sunken logs, deep in the benthos (the substrate at the bottom of a body of water), or wedged into the cracks of bedrock. And they might be in places where the current, or predators like alligators and snapping turtles make it perilous for biologists to seek them by diving an sticking their hands into dark places underwater! So I’m enjoying reading about other ways of modeling where they might be found.

- Suetonius' Lives of the Caesars, especially the section on Julius Caesar. Julius Caesar is remembered for many things, but if you click that link and then search for “pearl” you’ll see some of the ways mussels appealed to him. You might be thinking “Don’t pearls come from oysters?” Yes, they do. But they can also come from many other mollusks that have nacreous shells, including snails. Some freshwater mussels are called margaritiferidae, from Latin words that mean “pearl-bearing.” They are among the most threatened of the unionid freshwater mussels. The nacre inside unionid mussel shells is what many contemporary shirt buttons imitate, harking back to a century ago when we harvested mussels by the tons out of our rivers to turn them into pearly shirt buttons. Our quest for fashion did tremendous harm to the health of our rivers and left us with much dirtier water. Suetonius points out that Julius Caesar also had a taste for fancy pearls, and could guess the value of a pearl by holding it in his hand. He outlawed wearing pearls for most of Roman society, and gave a particularly large pearl to one of his mistresses. That pearl was worth six million sesterces, which is almost unimaginably expensive. Something about pearls really catches our eye, and Suetonius tells us that Julius Caesar’s invasion of Great Britain was motivated by his desire for pearls.

- Jesus told a story once about someone who was willing to sell everything he had to buy a single pearl. Those few sentences have had a broad effect on religions around the world. They also tell us something about the economy of fashion two millennia ago. Julius Caesar died a few decades before Jesus was born in a small part of the Roman Empire, so Jesus might well have been familiar with the elite Roman taste for pearls. Perhaps he had Julius Caesar in mind when he spoke of that man who sold everything. If so, that would turn Jesus' parable into a political commentary.

Pearls

Reading this morning about freshwater mussels (surprise!) in four contexts:

If you know me, you know this is where I live: the intersection of classics, great texts, religion, invertebrate and riparian ecology, mathematics, and clean water. I need a simpler way to describe the intersection of my interests, but for this morning I’ll leave it at this:

This morning I’m reading about pearls.

On The Religious Architecture of Water

One of my recent articles on Medium. Here's a sample:

If you want to know what someone believes, don’t ask them what they believe. Ask them where they spend their time, energy, and money.

Because the things that we genuinely believe are things we act on.

And soon the landscape around us becomes the outward form of our inward beliefs.

IBM’s Call for Code 2021

IBM just released their latest "Call for Code." If you have a team with some coding skills and you want to put them to use helping others to tackle some intractable problems, click that link and dive in!

I have a particular passion for clean water, but each one of the problems they're inviting people to work on are worthy of our time and attention.

Environmental Studies At Augustana - My recent interview with Lori Walsh on SD Public Radio

| |

| The Augustana Outdoor Classroom, designed by an Environmental Philosophy class. |

Aldo Leopold wrote that "there are two spiritual dangers in not owning a farm." Those dangers both add up to this: losing touch with the land and so with the very things that sustain our lives.

You can hear the full interview here.

|

| Strawberries in spring bloom. Do you know where your food comes from? |

My thanks to Lori Walsh for being such a patient and thoughtful interviewer. In the past I've been interviewed while sitting with her in her studio. Phone interviews are new for me, and there's a little lag that has me talking over her unintentionally at the end. She rolls with it, unflappable and brilliant as always.

Teaching Tropical Ecology in Belize and Guatemala

|

| Sunrise on the Barrier Reef in Belize |

In this post I'll try to answer some of the questions that we are often asked about the course. Probably the most common question is "What do you do in your course?" The second most common must be "How can I teach a course like that?" I'll start with the first question:

What do you do in Guatemala and Belize?

The short answer to this question is a lot. I'll try to summarize.

Our approach to tropical ecology includes the standard elements you'd find in any ecology course: our students read a lot about the ecosystems and the prominent species of plants and animals they're likely to encounter. We teach them what we know about the systems we think we understand, and we tell them about the big gaps in our knowledge that we're aware of - knowing full well that we likely have blind spots we aren't aware of.

In Guatemala this means learning about the ecology of a dense forest growing on a karst plateau, and a deep lake where the water does not circulate much.

In Belize we study the mangroves and the barrier reef. The mangroves are like a porous filter between salt and fresh water, like a cell wall on a macro scale. They serve as a buffer against hurricanes; they keep topsoil from eroding into the sea, and they are a rich and colorful nursery for thousands of species.

The Importance of Human Ecology

We want our students to learn much more than the plants, animals, soil, air, and water, though. Perhaps more than anything, we want them to learn the human ecology of the places we visit. Ecology is not merely an academic study; it is, at its heart, the study of both the world and of our place in it. We don't just look at macaws, jaguars, vines, and ceiba trees; we look at the way our lives - even our visit to these amazing places - affect and are affected by these plants and animals. We don't stay in hotels; we rent rooms in local homes, and we eat meals with local people. We hire local teachers to teach us Spanish and the Itzá language. We study the history of the Itzá people, and we visit ancient ruins. We walk through the forest and camp overnight with local guides who can teach us what they know of that place. We spend time playing soccer with a local youth group, we talk with and listen to local teachers, nurses, physicians, forest rangers, ecologists, NGO volunteers, government officials, town elders, and children. If the ecology of the place matters, surely it matters because these people whose ancestors have lived there for so long matter.

|

| Tikal |

|

| The church in San José, Petén, Guatemala |

In fact, even if you think they don't matter to you, if you're reading this post in North America these people do matter to you. If their ecology suffers, they will be forced to move to look for new sources of income and food. Simple-minded and disingenuous politicians will tell you this is a problem to be solved by erecting a wall on our border, but walls are a partial solution at best, and at worst, they are blinders that keep us from seeing the source of the problem; walls ignore the real illness and conceal the symptoms, as though willful ignorance were good medicine. The real question - in my mind, anyway - is why anyone who lived on the shores of Lake Petén Itzá would ever want to leave. The answer is that people leave beautiful homes when those homes cease to be liveable. Which means the medicine that is needed is one that treats the illness itself, and not just the symptoms. My students (I hope) return from our course no longer able to see Guatemalan immigrants to the United States as a mere abstraction. Break bread in someone's home and you will see that they are human, too, with lives as particular and intricate and important and rooted as your own. Only when we disturb those roots and strip away the soil must the lives be transplanted.

This is what I mean by human ecology.

|

| One of my students examining and being examined by nature |

Where do you go?

Our time in Guatemala is chiefly in central and northern Petén. Until recently, the landscape of northern Petén was dominated by dense forest, mostly old-growth lowland forests. Surface water is mostly wetlands that vary considerably from one season to the next. There are several small-to-medium-sized rivers, and small streams, but I think a good deal of the water flows underground in karst formations; the Petén has thin soil over a wide karst plateau. There is not much water flowing on the surface. In the center of Petén there is one very deep lake, Lake Petén Itzá. This is a gem in the forest. Flying over it on a sunny day you can see the shallows fade from pale green to rich emerald, and the depths along the north side of the lake plunge to amethyst and dark sapphire. The lake has no obvious inflow or outflow, except a few small streams flowing in from the south and west, and a little creek flowing out in the east.

|

| My students leap into Lake Petén Itzá to cool off. |

In Belize we spend most of our time on one of the barrier islands that have no permanent residents. We use that island as a home base from which we can boat out to patch reefs, mangroves, turtle grass beds, deep channels, and the fore-reef. We snorkel with our students in all these places, slowly gathering experiences of similar species in diverse environments, so that the students (and we) can see both the ecology of small places and the web of relations between those small places. In mangroves, for instance, we might see juvenile caribbean reef squid that are a few inches long. When we see them on patch reefs, they might be five or six inches long, and in deep water they might reach eight inches. Each location gives us a glimpse of another stage of their life cycle.

|

| My students watch the sunset in Belize |

Why do you do this? Aren't you a Humanities professor?

Even if people don't often ask me this, it's obvious that quite a few people think it. Yes, I'm a professor of philosophy and classics, and I teach religion courses, too. But for my whole life I have been fascinated by life underwater. My most recent book was the result of eight years of researching the lives of brook trout in the Appalachian mountains, and much of my research now has to do with ocean and riparian environments in Alaska. I don't do much of what would count as research in the natural sciences, but I do spend a lot of time observing nature. This is both because I find it beautiful, and because I think it's a bad idea to try to formulate ethical principles about things I haven't experienced or seen firsthand. Of course it's not impossible to write policies about things one hasn't done; one needn't commit larceny before writing a law prohibiting theft. But experience teaches me things I might not learn in other ways, and that can keep me from trusting too much in my own opinions. As Aristotle put it,

“Lack of experience diminishes our power of taking a comprehensive view of the admitted facts. Hence those who dwell in intimate association with nature and its phenomena grow more and more able to formulate, as the foundations of their theories, principles such as to admit of a wide and coherent development: while those whom devotion to abstract discussions has rendered unobservant of the facts are too ready to dogmatize on the basis of a few observations.” Aristotle, De Generatione et corruptione, 316a5-10 (Basic Works, McKeon, trans.)I want to "dwell in intimate association of nature and its phenomena," and being able to formulate better principles is a nice side effect of doing so.

How Can I Teach A Course Like This? Can others participate in this trip?

The answer to the second of these questions is both yes and no. When I'm in Guatemala and Belize, I'm teaching. Unfortunately, this means I don't have time to bring others along and act as their tour guide.

However, the people I work with in Guatemala - the Asociación Bio-Itzá - would be happy to have you come for a visit. They're in the small town of San Josè, Petèn, Guatemala, right on the north shores of the lake. And this is the answer to the first question. Want to teach such a course? Get in touch with Bio-Itzá and they can help you set it up.

You can get to San José by flying or driving to Flores, then going around the lake by bus or car to San José, about a twenty minute drive.

|

| Flores, Petén, Guatemala |

In San José they have a traditional community medicinal garden. Just north of town is the Bio-Itzá Reserve, where you can go for guided walking tours or overnight stays. It's rustic and gorgeous. (Visits to the Reserve must be arranged in advance through Bio-Itzá.)

When you stay in San José you can easily take a launch (a wooden motor boat) across the lake to Flores, the seat of Nojpetén or Tayasal, the last Maya kingdom that fell to the Spanish.

Flores is a pretty place as well, and I like to take my students to visit ARCAS to see their animal rehabilitation center. (There's a great documentary about that place that was on PBS this year called "Jungle Animal Hospital.")

|

| Scarlet macaws being rehabilitated at ARCAS so they can be released back into the wild |

If you stay in San José, you can also take a short trip (about a half hour by car) to Tikal, or to Yaxhá, both of which are amazingly well-preserved Maya ruins. A little further past Tikal is Uaxactún, where you can see more ruins, and you can also visit a community that is trying to practice sustainable forestry.

This region is not like the tourist areas of Western Guatemala; it's more like the rural frontier of Guatemala, a long-neglected place that is now at risk of being overrun by slash-and-burn forestry, cattle farms, and oil development. It makes me think of the Dakotas over the last century; the population is small and indigenous, and most people in power in Guatemala seem to consider the forest to be a wasteland that is better burned down than preserved. I do not share that view, and while I know that more tourism will bring development and other risks to both culture and forest, the risks are already there in other forms. I hope that ecotourism will offer some counterweight to the other kinds of development that don't seek to preserve the biological integrity or cultural history of this place.

South Fork, Eagle River

The houses here are ugly. Taken on their own, any one of them is a beautiful building. Plainly this is spendy real estate in God’s country. But the houses look like they were lifted from the pages of some little-boxes-full-of-ticky-tacky architectural lust propaganda and carpet-bombed on the hillside, then allowed to remain wherever they fell. There is no order, no sense that the houses were built for the place. Every one of them is a garish, angular excrescence on the opposite hillside. No doubt their inmates would disagree with my assessment; they only see the houses up close, and from the inside. They must have no idea how out of place their unnatural rectangles look against the sweeping slope of the Chugach Range. No doubt, when you’re on the other side of those big plates of glass, gazing over here at the state park over your morning K-cup, the view is precious. But when you’re in the state park, looking back, there is nothing on the opposite hillside to love. Over here, there is only regret that these people believed that you could buy both the land and the landscape.

It’s about three miles’ hike in to first bridge in state park. A fairly easy up-and-down walk. It’s raining. Spitting, really, what they call chipichipi in Guatemala, a constant drizzle. The sky is a palette of cottony grays that have lowered themselves onto the mountaintops. There is a clear line below which the mountains are visible. Above it, clouds roll and shift.

I shiver a little in my heavy raincoat and think about putting on my rain pants, but I know I’ll be too hot if I do. Some of my students are wearing shorts.

At the footbridge we sit and eat our lunches. The university has packed us red delicious apples (a mendacious name), bags of honey Dijon potato chips, and turkey sandwiches with lettuce and onions. It’s not good turkey, but no one cares. This is a lovely place. We have other food in this place.

The river is only fifteen feet wide here, and it is the color of chalk, like diluted Milk of Magnesia. Taking off my shoes, I wade in. Immediately my feet start to ache with cold. Turning over a stone, I look at its underside. The gray water drips off and a tiny larva wriggles to get out of the light. It's too small to identify it, maybe a miniscule stonefly. A huge blue dragonfly cruises over the river, darting past me.

There are lots of wildflowers up here. One of my students is on the ground with her laminated guidebook, puzzling over one specimen. I've been carrying these guides everywhere, but they're only helpful for about seventy-five percent of the common stuff. There's just too much life here to get it all in a book.

The flowers grow in so many colors, so many strategies for getting the scarce pollinators' attention in the brief summer. Yellows, purples, and blues predominate. The guidebook warns me about several of the purples: DO NOT EAT THIS! Some of them are poisonous. So are a few of the yellows. This is a beautiful place, but it's also a harsh place, and life clings to the edge. Poison is one good way not to get eaten, I suppose. Looking up the mountain, the trees give way to shrubs a hundred yards above us. A hundred yards more and there's only grass. Above that, I can only see rock.

Some of these plants have another strategy: rather than avoiding getting eaten, they invite it. Berries are the way some plants make use of animals to carry their seeds to new places. Bear scat, full of seeds, is all along the trails here. Each mound is a nursery where some new plant may grow in the fertile dung.

There is a kind of berry like a blueberry that grows on something that looks like a mix between evergreens and moss, only a few inches high. Some people call it "mossberry," appropriately. Some locals call it a blackberry. Matt tells us they're crowberries, as he gathers a handful. He eats some and then the students tentatively pick and eat some too.

We spend three hours there at the bridge, observing. There's so much to see. Some of us write, some draw, some stare at the peaks that surround us. A few doze off. I get out my watercolors and try to paint the landscape, but I'm quickly frustrated. There are so many greens and grays and blues, and I'm no good at mixing colors. I keep painting anyway. I can at least try to get the shapes right, I think, but I'm wrong about that, too. The mountains are stacked up in layers, and the lines look clean and clear at first, but when I try to focus on them they blur into one another. The hanging glacier at the end of the valley looms over us, silent and white and yet so eloquent. The glaciers are what made all of this, and even though they have retreated, the river runs with their tillage, the plants grow in their finely ground dust, the smooth slopes were ground smooth by millennia of ice.

Upstream, Brenden hooks his first-ever dolly varden. This is his first fish in Alaska. He is positively glowing with delight. He cradles it in his hand and then quickly returns it to the water pausing only to admire this vibrant glacial relic of a char. It too depends on the glacier.

The temperature is constantly shifting as the sun comes in and out of the clouds. Each part of the valley takes its turn being illuminated: the river shines like silver; the mountainside glows bright green and the rocks and bushes above the tree line cast sharp shadows; high in the valley small glaciers are bright ribbons streaking the blue granite. The clouds push the sunlight in ribbons across the valley. When we are suddenly in the light, we are warm.

After a few hours we walk back to the car. No one wants to go. For a while we drive in luminous silence.

Interview on SD Public Radio

Click here to listen to the whole interview.

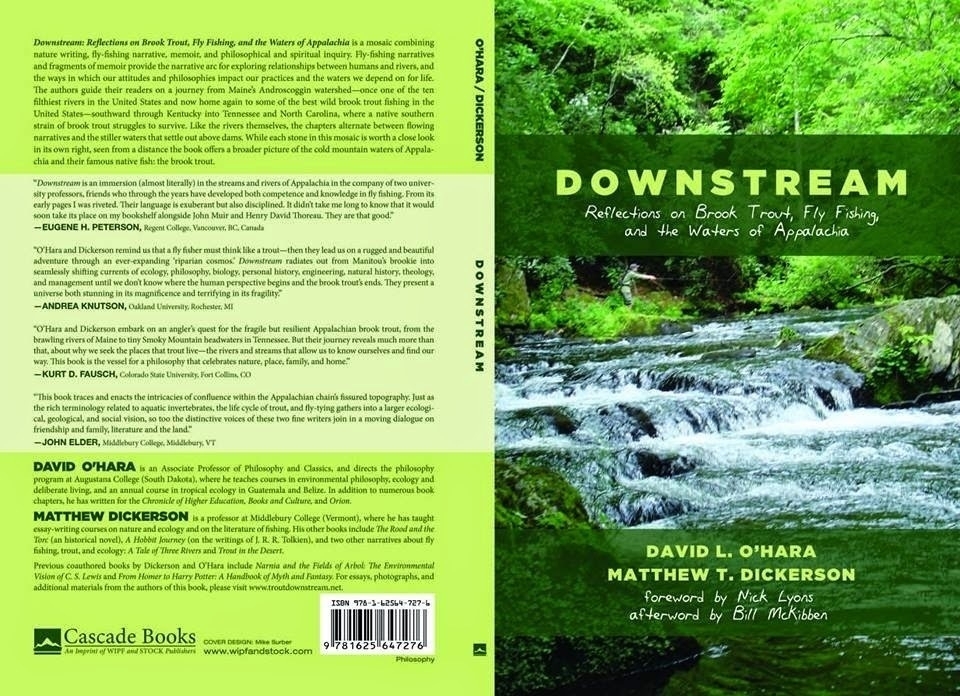

Downstream: My New Book On Brook Trout and Appalachian Ecology

It is now listed on Amazon as well, though not yet in stock there.

I'm very grateful for the foreword by Nick Lyons, the afterword by Bill McKibben, and the kind words offered by such a wide range of brilliant scholars of theology, literature, and science, like Eugene Peterson, Andrea Knutson, Kurt Fausch, and John Elder.

Hope And The Future: An Open Letter To The President

I know you've got a lot on your mind right now, and I don't envy you the burdens of your office. I pray for you often, asking God to give you the wisdom to make good decisions and the strength to carry them out.

I have two requests for you today. The first is, please don't give up on hope. In your first campaign you spoke about hope a lot, and I think you know that meant a lot to people everywhere. We all want hope, especially hope that we feel we can believe in. We will often settle for unreasonable hopes, but we prefer hopes that seem grounded in possibility rather than in wild fantasy. For a while there you sounded like you had both hope and reason for hope. When I think about the office you occupy, I imagine there's a lot that works to rein hope in, to tame hope and to break it. You start out with big ideals, and then everyone reminds you that limited resources will be made to seem even scarcer by partisan quarrels until there's nothing left to spend on dreams. But let me tell you this: we need you to make lots of small decisions, but we also need some big dreams, some reasonable hopes. We need someone who will climb the steps to the bully pulpit and preach a sermon that reminds us of "the better angels of our nature." Don't just make the little decisions; remind us of the great hopes that have lived in our nation.

I have two requests for you today. The first is, please don't give up on hope. In your first campaign you spoke about hope a lot, and I think you know that meant a lot to people everywhere. We all want hope, especially hope that we feel we can believe in. We will often settle for unreasonable hopes, but we prefer hopes that seem grounded in possibility rather than in wild fantasy. For a while there you sounded like you had both hope and reason for hope. When I think about the office you occupy, I imagine there's a lot that works to rein hope in, to tame hope and to break it. You start out with big ideals, and then everyone reminds you that limited resources will be made to seem even scarcer by partisan quarrels until there's nothing left to spend on dreams. But let me tell you this: we need you to make lots of small decisions, but we also need some big dreams, some reasonable hopes. We need someone who will climb the steps to the bully pulpit and preach a sermon that reminds us of "the better angels of our nature." Don't just make the little decisions; remind us of the great hopes that have lived in our nation.The second request is related to the first: I'd like you to help us to nurture the reasonable hope that we can find new ways of making energy. There are powerful sermons being preached about building more oil and tar sand pipelines so that the old ways can be maintained. But those are sermons without hope, the sermons of a creed doomed to perish in fire and smoke of its own burning, the platitudes born of a faith in a limited and dwindling resource. They are the cynical homilies of those who pass the collection plate and who think the worst thing they can lose is our regular tithing to the god of petroleum.

We need a reformation in that way of thinking.

Because national security is not just about defending ourselves with bullets and bombs, and it's not just about making sure we have enough oil. In the long run, national security has to mean that we have taken good care of the land, so that it is still worth inhabiting. That, in turn, means we have nurtured our hearts and minds and cultivated our virtue. What, after all, does it profit a nation to gain the world and lose its soul? We are a nation of innovators, not just custodians of the status quo. We began as an experiment, and it is in experimentation and new thinking that our hope now lies.

We can begin by directing more funding to universities. We need bright engineers who have the freedom and funds to investigate how to make more efficient solar and wind energy.

We also need bright students in the humanities who will help us form the best policies to make sure we use our technology well. After all, a democracy can live without engineers, but it cannot survive long without reporters, teachers, and lawyers.

We know that money spent on education pays a perpetual dividend to both the person educated and her whole community.

We can also encourage the creation of new and important prizes. Why should we not have more prizes like the Nobel Prizes? And why shouldn't such a proud and wealthy nation fund some of those prizes? You've got the ear of the world for a little while longer. Use that opportunity well, and urge us to put our private funds into prizes for people who advance the causes that matter most to humanity: growing good food, creating and preserving clean water, protecting the species God told us to care for, healing the sick, liberating captives, and making us better producers and consumers of energy.

I am grateful for people who willingly take on the burdens of public office. I don't imagine it is easy. You remain in my prayers.

David

20,000: Two Stories Of Water Pollution In The Dakotas

The first was a story about an oil pipeline leak in which 20,000 barrels of crude oil contaminated over seven acres of farmland. The Argus reports that in major oil-producing states like North Dakota oil spills must be reported to the state, but state law does not mandate the release of this information to the public. In other words, the state is free to keep this news quiet. One has to assume that the state legislators who wrote that law thought it was in the public interest to keep news of toxic spills quiet. It's better for us not to know about such things, I guess.

Anyway, the Argus lets us know that some state officials think there's no cause for concern: "state regulators say no water sources were contaminated, no wildlife was hurt and no one was injured." Oh, good.

The second story is about the disposal of some 20,000 cattle that died in a surprisingly early and heavy snowstorm earlier this month. This is a devastating loss for ranchers across western South Dakota. It represents an enormous financial loss, and it also creates a very difficult cleanup problem. The best solution for disposal of all the carcasses so far has been to dig two large pits. The Argus reports that there are strict regulations concerning the depth and soil of the pits.

According to the Argus, the reason for the pits is to make sure the dead cattle don't contaminate streams.

Which makes me wonder why there is so little concern for the oil spill in North Dakota. Obviously there is an important difference between bacterial and viral infections entering streams, on the one hand, and oil entering streams on the other hand. But surely both represent serious health hazards?

We are left with a peculiar contrast: a few cattle on the ground - something that happens in nature all the time - are a serious threat to the water, while a million gallons of crude oil spread across seven acres of farmland (presumably some rain falls there and washes into streams?) is barely worth telling the public about.

*****

Update: Since a number of people have asked me just what happened to the cattle in South Dakota, I am posting this link that I found to be a helpful reply to some questions about the storm and the loss of the cattle.

Free Stone

The memory of that short walk remains one of the strongest from my childhood. The river had cut new banks, and had changed its own course. We walked along the round gravel banks and gazed up at the undercut roots of massive oaks and pines. We saw the bones of the earth laid bare by the river's irresistible blade. The river had cut itself a new bed. Everything in its path was destroyed; everything in its path was made new.

|

| Polished by the river. |

Since then I have walked hundreds of miles along - and often in - deep, clear waters over cobbled riverbeds. The sound of the water is the music of my soul, high sprinkled notes of splashing water and bass tones of massive stones rocking back and forth in the current. Walking in freestone streams makes me forget my worries, forget time itself.

The Other Drones Problem: The Tragedy of the Unexplored Commons

But there is another ethical issue related to UAVs that doesn't have to do with war. Or, if it does, it has to do with a "war against crude nature."

The technologies we invent in wartime don't go away when the conflicts end. Already, UAVs are being deployed for a number of other uses, and we can expect their uses to increase. I'm no flag-waving Luddite here. The things we invent can be put to diverse uses, some helpful and some harmful. But if we care about promoting the helpful uses, we'll need to be intentional about that.

UAVs are a brilliant platform for remote-sensing technologies. They can cover a lot of ground and stay aloft for a long time. Drone aircraft are adding to our ability to conquer unknown spaces. If you've used Google Maps to explore places you've never been before, you know what an aesthetic boost and letdown this can be: it's a boost to see what you've never seen, and at the same time, we find ourselves sharing Aldo Leopold's lament in "The River of the Mother of God": the unknown places are being replaced by maps, and our deep genetic need to explore runs up against the feeling that everything has already been seen. When I lived in Madrid, I tried to make places like the Retiro park my places of natural exploration and solitude, but I couldn't escape the feeling that I was treading where millions of others had already trod.

|

| We have a deep need for exploration, and so we need places that feel unexplored. |

But that is a small worry compared to the bigger issue of the world's oceans and natural resources. For the whole history of our species we have been able to act as though the world contained unlimited resources. Our species is an explorer species. We have "restless genes," as a recent National Geographic article put it.

Gone is the age of Hemingway's Old Man and the Sea. We no longer take to the seas in small craft and fish commercially with handlines. The last century has pushed fishing fleets thousands of miles from the places where they will ultimately bring their catch to market. We can no longer treat the oceans as limitless resources; we are fishing them out, and some species may collapse under the pressure and never come back.

In the race to find the last remaining schools of fish, we are beginning to use UAVs to scour the seas. Where fishermen once looked for birds circling schools of sardines, robot airplanes now skim the waves and do the searching for us.

|

| At the crossroads |

Ethicists and game theorists refer to this as the "tragedy of the commons": if we each only take resources in proportion to what we can use, the resources can be shared indefinitely. But if some of us take more than our share of the "commons" or the resources, they will have a short-term gain at the expense of the long-term gain of everyone.

The STEM fields (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) are brilliant, and wonderful. New technologies give us new access to the world, and they can save and improve lives. But they lack the ability to regulate themselves, which is why as the STEM fields grow, we need the humanities (and their critiques of technology) to grow with them. If we are not careful, new technologies can also permit us to do great harm to our common world - and to ourselves. If fish seems cheap and plentiful, stop to ask where it came from, and whether that source is sustainable. If it's not, vote with your dollars and eat something else.

People Of The Waters That Are Never Still

My family has since lost the languages those ancestors spoke, and this fusion of tribes has adopted the linguistic fusion of English. I have no intention of claiming a legal place among either of the nations from which I am descended, nor even to name them here. But I find that the memory of both, and of the lands they lived on, is rooted deeply in my consciousness of who I am. Last year, while visiting the British Museum, I saw a display of various Native American peoples, including my own. It was the only time a museum has moved me to tears. The words and ways of my forebears may be mostly gone, but they are not forgotten. My father taught me to remember them and what they knew of the land we lived on, and often, while teaching me to know the woods, he would remind me that those woods were old family acquaintances.

Jacob Wawatie and Stephanie Pyne, in their article "Tracking in Pursuit of Knowledge," cite Russell Barsh as saying that "what is 'traditional' about traditional knowledge is not its antiquity but the way in which it is acquired and used." Our word "tradition" comes from Latin roots that mean something like "giving over" or "handing down." Traditional knowledge is knowledge that is a gift from one generation to the next, a gift we give because we ourselves were given it. I am grateful to my father, in ways that I may never have told him - in ways that perhaps words cannot begin to tell - for the traditions he learned and loved and passed on to me. I'm grateful that he has not let me forget.

There is, of course danger in emphasizing one's heritage and one's roots, especially if we make that the source of a distinction between ourselves and others, or a way of diminishing the lives and traditions of others. Just as much as it matters to me that I am from the people of the waters of the Catskills, it matters to me that my ancestors shared those waters with one another, people from two continents recognizing, each in the other, the waters from which both arose.

For all that I have received, for the traditions like waters pouring over the cliffs, gifts like the Kaaterskill Creek, let me give thanks. Let me give thanks with my life, offering to those who come after me, a taste of the sweetness of those same waters.