Under this tree

Inatead of posting photos of my newborn granddaughter to the internet I’m posting a few sketches. Here’s a glimpse of a tree under which my daughter held her daughter for a while in a park in Chicago.

I’m making a book of these sketches, and notes to go with them, to give to her someday.

And of course they’re helping me to move slowly and cherish these moments.

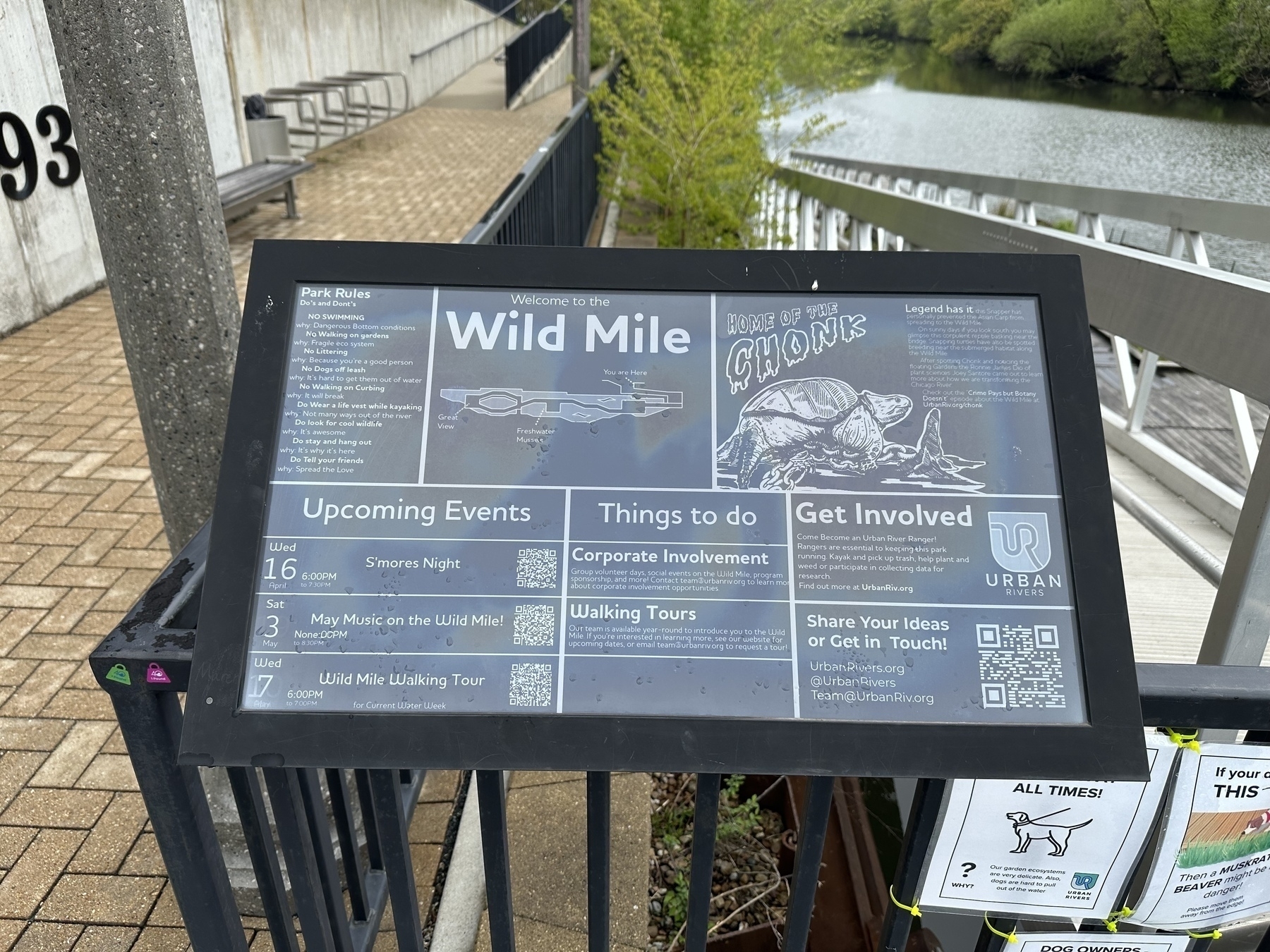

Wild Mile in the Chicago River

Went for a run this morning from my daughter’s house over to the Wild Mile at Goose Island in Chicago.

I love seeing what Urban Rivers is doing here: education, recreation, and habitat for multiple species. Brilliant.

I’m a fan of signs that inform people and empower them to make beneficial choices. Signs are like little books: they continue to teach even when the author is not present.

It’s not a mile long yet, but it grows a little each year, adding more floating platforms for plant an animal habitat.

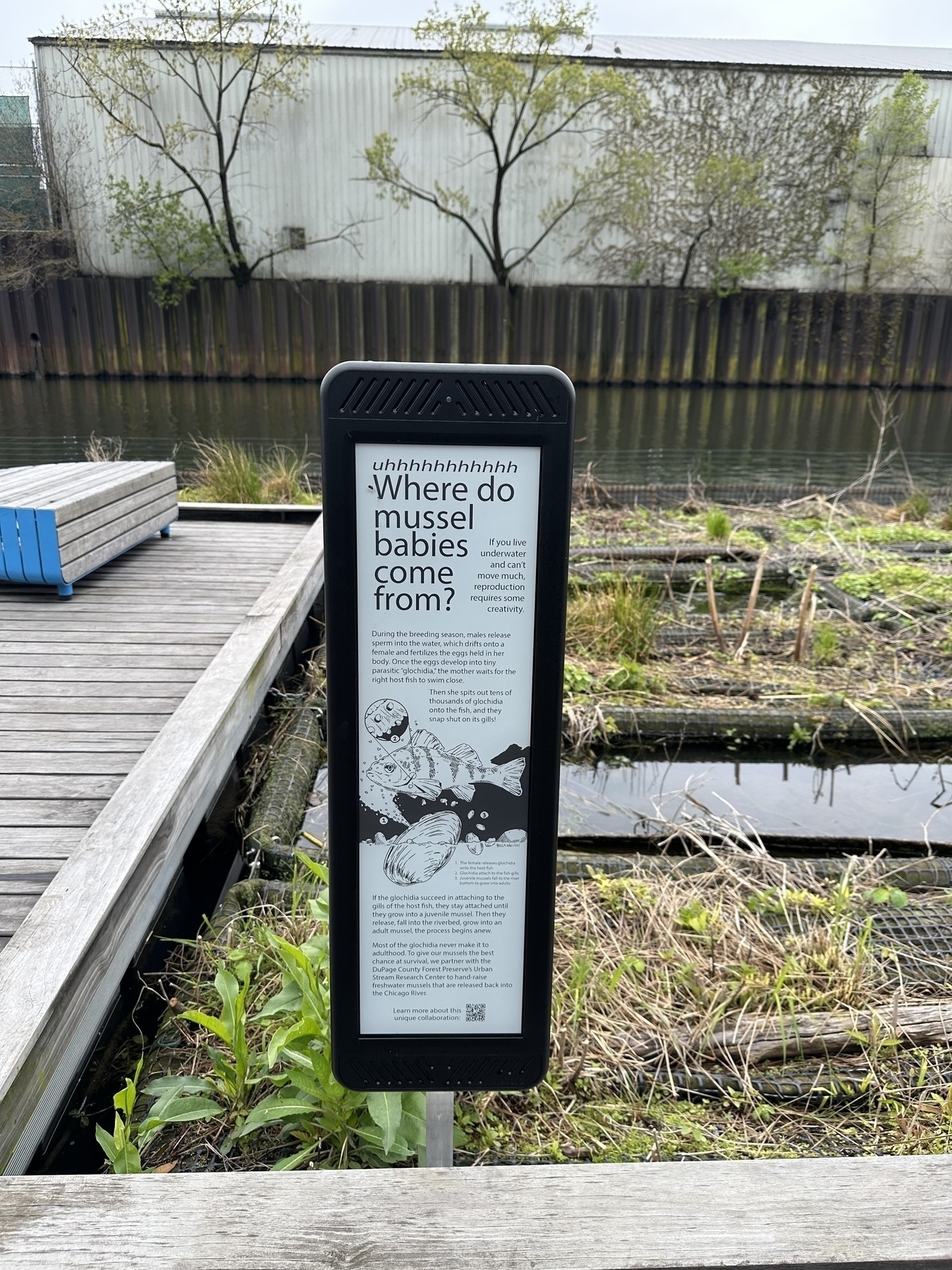

One of my favorite parts: they’ve created native freshwater mussel habitat, and are educating people about why mussels matter.

Also, I want to make one of these chaises longues for two and hide it somewhere on my campus.

If you enjoy this as much as I do, consider supporting something similar in your own community, like Friends of the Big Sioux River.

Grow more than grass

An article in The Christian Century about the new Episcopal Grasslands Network, and the gathering we had in Topeka, Kansas last week.

Happy to see my alum Raghav (an environmental scientist and educator in South Dakota) and our work on our university campus and at our parish mentioned here.

If you live in our region and want help transforming land into a place that teaches, regenerates, and feeds your neighbors, let me know.

A reminder that I am not God

There are many reasons not to believe in a God, and I don’t disparage those who don’t share my belief. Instead I will simply testify that one of my reasons for believing is that it is helpful to be reminded by my community that my view of things is just that. I don’t see with God’s eyes; I can only aspire to do so.

I have written a longer version of this here, with some references to the Stoic philosophers who help me to explain this view.

The Danger of Caring

“It’s just so rough here in this country right now. Doing some river fishing to survive.”

Mark and I met many years ago when I was teaching a tropical ecology class in Belize. He was a teenager with an entrepreneurial spirit. He knew where the little boats would meet folks like me to take us out to the research lab thirteen miles off the coast, and he was always there to meet us, and to sell us things he had made. I always bought something: a flint knife, a toucan carved of volcanic rock, a couple of bracelets.

In his forward-thinking way, he asked me for my email address fifteen years ago, and every couple of years he sends a quick note to find out when I’ll be back. Unfortunately my university has replaced that class with another, and I no longer teach it. It was one of my favorite classes. We’d live with local families while learning about the history, culture, and languages of Petén, then we’d go on a forty-mike hiking and camping trip through the rainforest that ended at the Tikal national park. We’d end the course with a week on a barrier island, snorkeling and learning about coral ecosystems. It probably wasn’t a very efficient course, but wow was it good.

And one of the best parts of it was meeting people, and spending time with them.

As my friends and family know, this is also one of the hardest parts for me, because the danger of getting to know people is that you might start to care about them.

When a hurricane makes landfall in Central America, I look at the map and think of where my friends are. Are they safe? Merlina’s roof in Guatemala wasn’t in good shape when I saw her last time. The ladies who are building that business in northern Costa Rica got flooded out last year; I hope they’re okay. My Itzá and K’ekchi’ friends who work in the forest—are they safe at home or are they riding things out with the other guides and rangers? How are the kids? And so on.

It’s similar when the challenges are more local. A friend’s daughter was killed in an automobile accident last year, and my friend is struggling with the loss of her job shortly after losing her daughter. When Covid hit, I knew my friends in Central America would be among the last to receive help. My mentor and teacher died of Covid and my heart still aches for his family and for the whole community.

I hadn’t been back to Guatemala or Belize since my class was last offered seven years ago. I’m in touch with my friends there almost every day, and while texting and emailing is great, not much beats having a meal together. Last month my wife and I decided to buy tickets and fly to Guatemala to reconnect.

In some ways, things have gotten better. The town where I have spent most of my time has seen some new investment, and the lakeshore has all been developed. The downside is that the investors are generally from other places, so the locals have a harder time getting access to the lake they’ve known since time immemorial. Hopefully the new restaurants and resorts boost their economy and some of that trickles down to the poor?

But the hardest part was hearing story after story about how recent changes in our government have devastated the local economy. I visited a forest reserve where the rangers’ bathroom is half renovated. The remaining renovation was going to be funded by a few thousand USAID dollars. That got cut off, and so the bathroom has no water other than what falls through where the roof used to be.

In another part of the country friends told us about how one small community lost 40 jobs that were funded by USAID. When you consider the median income in Guatemala (it’s a few thousand dollars a year last I checked) that doesn’t amount to much money. When you consider those jobs were helping to create other jobs, to protect natural resources that make life easier, to promote agriculture and business, and to prevent contraband trafficking, we were likely getting an extraordinary ROI on that money.

There are times when I wish I had taken a different line of work, one that kept me comfortably within the borders of my own country. Or maybe I’d only leave my country to go to resorts, and never rent a bed in a home with questionable plumbing, a corrugated tin roof, and walls that crumble if it rains too much.

The danger of my job is I get to know people. I play games with their kids, and I have meals in their homes. I learn their names, we exchange gifts and phone numbers, we start to care for one another. When those storms hit, or when economic storms hit, or when we suddenly cut off funding that others hoped might help them to help their country become healthier and stronger, my heart aches.

I only know Mark from that one dock in Belize. Maybe his email isn’t about fishing for food but he is actually phishing, a ploy to get me to send him a few bucks. Thing is, I’ve met him often enough that I worry about him, and his family, and his community. I’ve seen the fragility of his ecosystem, and I’ve seen the fragility of his country. And I’ve known so many people in poor countries who find themselves in despair. Does no one hear our call for help? Does no one care?

Don’t mistake me for someone with great solutions. I’m not an economist, not an international development expert. I don’t have great wealth or great influence. I’m a teacher who specializes in philosophy, religion, classics, and ecology. I know a little, not a lot.

But some of the little I know remind me of that phrase “the least of these” and I find it hard to turn my back and ignore those whose hands I have clasped, who have shared their morning meal, who have prayed for my children even as I have prayed for theirs.

In another, imaginary world I’d have all the answers, all the money and power to solve all the problems.

In this world I have only a heart that aches when Mark writes to tell me he is fishing in order to survive.

(In the image that accompanies this text: a white bus is parked near a rickety wooden seaside dock in Dangriga, Belize. That’s where I first met Mark. I don’t know when I’ll be back again, but I’d be glad to see him again, and even more glad to know that he and his family are thriving.)

Renewal

Springtime. We have been keeping a whiteboard in our kitchen to track the due dates of our friends and family who are expecting babies.

We also write phenological observations: first robin, first thunder, first daffodil, first lilac, first dragonfly of the season.

It’s a time of waiting, and we are turning our attention to the things we love to greet.

I sometimes worry about tornadoes, and I’m not thrilled about ticks and mosquitoes, but there’s so much good to watch for, and watching for those good things has been good for heart, soul, mind.

Shortly I will board a plane to meet my first grandchild, to hug my daughter who is a new mom.

My eyes are looking for the new joys, and my heart is full.

“Prairie Prophecy” - New Wes Jackson biopic

Really enjoyed the new Wes Jackson biopic, and was thrilled to be able to attend the world premiere in Salina, KS this weekend. Each time I go to Salina it feels a little like a pilgrimage. The prairie speaks volumes as you drive across it, but it speaks with a still, small voice.

I’ve met Jackson a few times, through a mutual friend who also teaches philosophy (and who appears in the biopic). Each time I’ve spoken with him I’ve been impressed with how much he says in a few words.

While he’s likely to be remembered for his work on perennial grains like Kernza, I admire his sense of design and connectedness in his Land Institute. The barn there is not for storage, but was built to house an idea, and to be a place of gathering. That’s brilliant.

Similarly, his labs have offices on the periphery and the coffeemaker in the center, so that the scientists don’t work in isolation. Jackson is often called a prophet because he calls us to pay attention to what we are neglectfully destroying.

But he also has a deep sense of mirth, and playfulness infuses all he does. His institute is a place of work, but it’s work with a shared mission, and it feels jovial rather than corporate.

His books express both these moods: urgency about what we are losing, and a practical approach to gathering us together for good work.

This reminds me of Wendell Berry (Jackson’s friend) who wrote in his essay “Racism and the Economy” that we seek technological fixes to our problems “because we have lost each other.”

Jackson and his team don’t shun technology—they’re plant and soil scientists using technology to renew agriculture for the whole world—but they also build things, like Jackson’s idea barn, to help us find one another along the way.

Here are a few photos of my last visit to The Land Institute’s Prairie Festival. I’m already looking forward to the next one in 2026.

If you want to preserve nature, get to know some part of it well.

Don’t stop with what you already know, or with the pretty things.

Try to find something small and neglected. A plain-looking insect. Something that lives underground. Fungus. Lichen.

If possible, let it be something you find unappealing. Wasps or spiders, maybe. Slugs. Something you can’t eat, and that isn’t for sale in garden centers.

Then look for the connections. How is it related to other living things? What depends on it?

Build your knowledge of its life-web. Think of it as one of nature’s neurons, connected to a much bigger neural system; what information does it share?

It doesn’t matter where you start. If more people knew a little, and if each of us shared what we know, we’d all know more.

It’s hard to save what you don’t love, and hard to love what you don’t know well.

At the premiere of the new Wes Jackson film here in Salina, Kansas.

The inaugural meeting of the Episcopal Grasslands Network at Grace Cathedral in Topeka, Kansas.

Good to see how they have used the land around the cathedral to make places of comfort, restoration, and food for the whole community.

On Teaching

When I read about the ways people who don’t teach fight over what schools should do, I am reminded how thankful I am to be able to teach my students as I do.

I want them to learn the delight of reading good books slowly and in conversation with others.

I want them to learn how to walk attentively across a fragile landscape and to see the small lives around them. And to stop and study that frog in a pool on the Katmai tundra, that orchid clinging to the side of a tree in Petén.

I want them to learn where their water and food come from, to work together to purify water as we hike, to consider how we have clean water at home, and how easily that could be lost.

I want them to wonder, as we walk together, who has no water purifiers, and what they drink when they and their children thirst.

I want them to marvel at the glaciers, and to see them here, now, as they are, slowly descending as the earth slowly (and sometimes suddenly) springs back up as the glaciers weigh less.

I want them to learn how to put up with one another and even to take joy in each other’s company as we walk through the talus, over the bogs, through the thickets of thorns, sweating under the weight of their backpacks, while cold rain drizzles on their heads. This is an important part of life.

And I want them to learn to love the things, the places, the people that are worth more than markets can ever measure.

If you ask me what I teach, I will tell you I teach people.

I just became a grandfather! So thrilled to meet my little granddaughter.

Planting Trees While Awaiting Resurrection

One more highlight came on Holy Saturday, when my wife and I planted fruit trees in our church’s growing food forest. The aim is to make perennial, low-maintenance food available to all who need it, for free. Far better than growing a lawn!

David Chin, and Bach's St John Passion

One of the best parts of the week was hearing the amazing David Chin conduct Bach’s St John Passion at the St Joseph Cathedral in Sioux Falls. My students who sang and played that night will never forget it. Those of us who listened likely never will also. David Chin also played harpsichord. Wow.

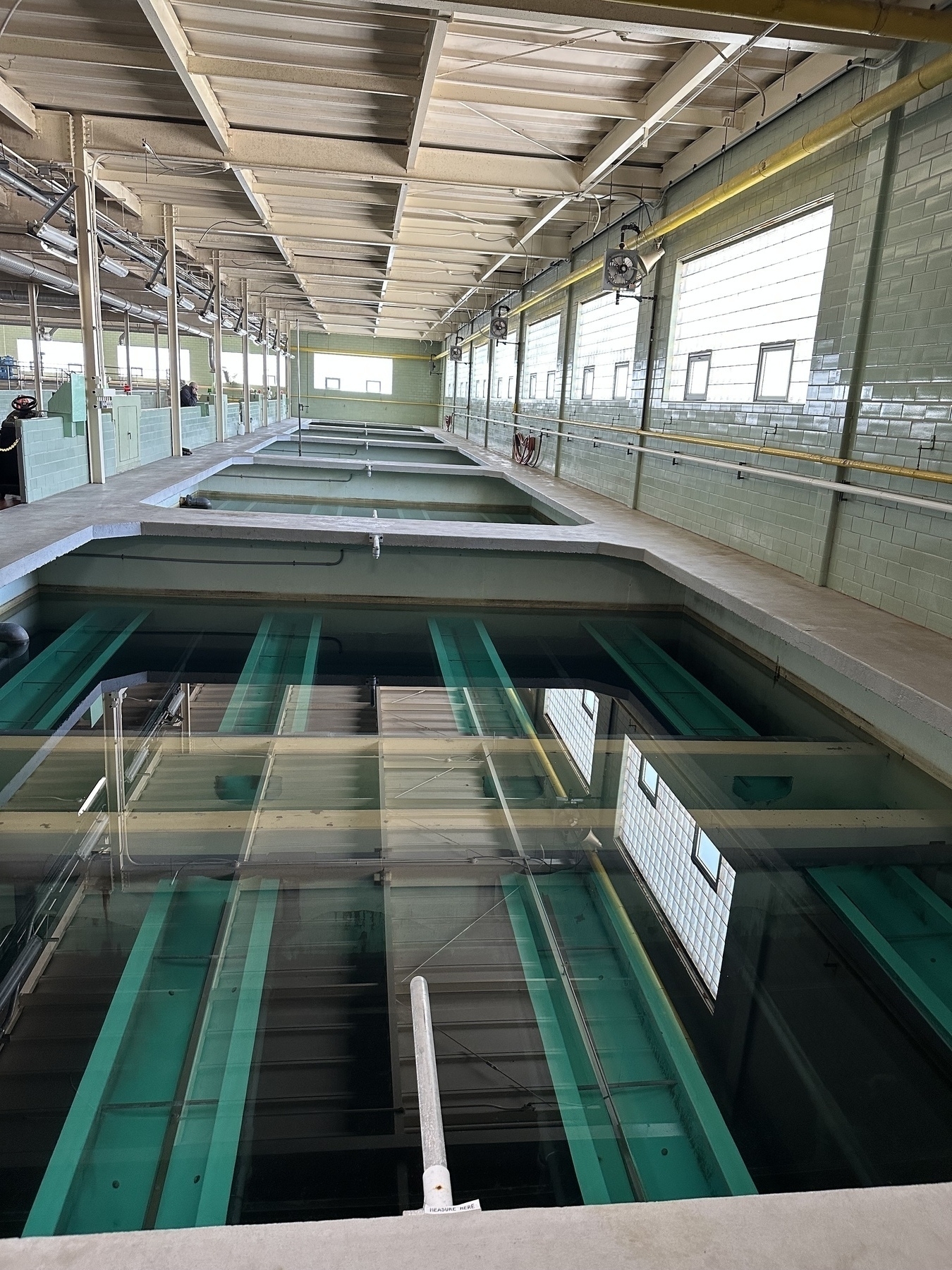

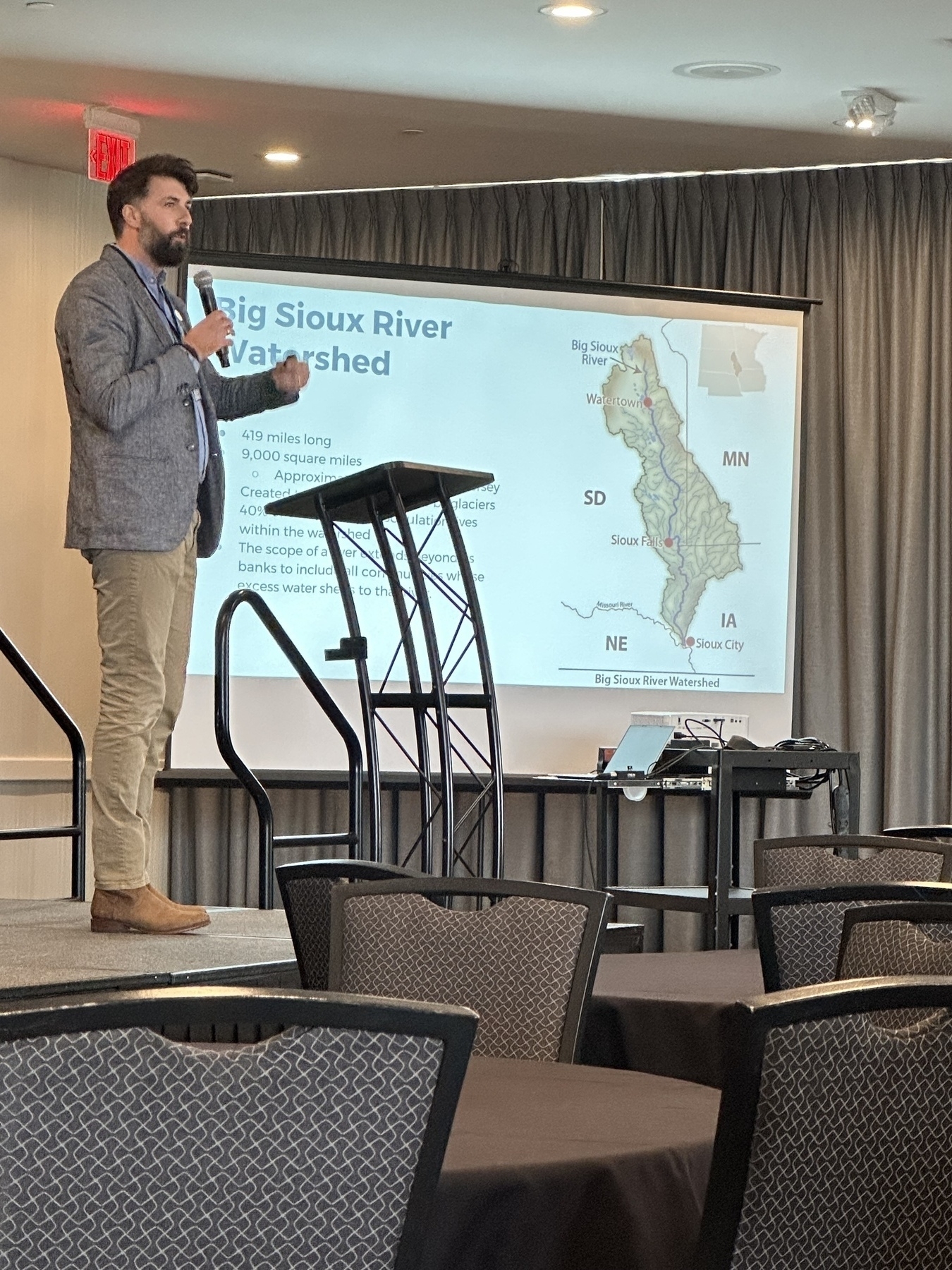

Big Sioux Stewardship Summit

As part of the Big Sioux River Stewardship Summit I got to tour our new wastewater facility, our water purification plant, Millennium Recycling, and some other sites where people are doing good work in beneficial community sustainability. So grateful for this opportunity and for these neighbors.

I liked how things looked in the recycling facility. There is beauty in recycling, whether it be the container with the single word “METAL” or the compacted aluminum cans that looked like abstract art. Millennium is alsoa second-chance employer that hires people who have been released from prison. They pay well and offer good benefits to people who might not otherwise find employment.

At the water plant I learned that Sioux Falls uses 2-3 times as much water per capita in the summer as in the winter. I asked why. The reply: “lawns”. Seems wasteful to use purified drinking water to water lawns, wash cars, and flush toilets. We need to start making multiple uses of water. It’s not hard, and others have already led the way.

<img src=“https://davoh.org/uploads/2025/7688d51ce9.jpg" width=“450” height=“600” alt=“A large metal bin on wheels, labeled “METAL,” is situated in an industrial setting.">

Great Talks at the Big Sioux Stewardship Summit; Shout-out to Lori Walsh

Some great talks by SDSU President Barry Dunn, Stephanie Arne, Lori Walsh of South Dakota Public Radio interviewing photographers Kevin Kjergaard and Greg Latza, and Travis Entenman of Friends of the Big Sioux River. Most of their talks are available on South Dakota Public Radio now.

Building A Floating Teaching Garden

Last week I spent some time building a floating teaching garden with my fellow Friends of the Big Sioux River Board members and some engineers from Raven Industries.

Social Media Fast

Last week, Holy Week, I (mostly) took a fast from email and social media. It felt great.

This week, I’ll do a little catching up, but not much.

Pilate, Not Pilates

Went looking for sources on the life of Pontius Pilate and the internet kept pointing me towards exercise regimens that happen to be spelled like the Roman cognomen. Argh.