∞

No Flash!

My job as a college professor brings me to a lot of museums and archives, and this summer has been especially full of visits to museums, historical sites, and archives in Greece, Norway, the U.K., and the U.S.

As a kid I found most museums boring, but now I really appreciate and enjoy them. I've spent many days of my life in the British Museum and in several museums in Athens, and each time I'm there I feel that time is rewarded with fresh discoveries and with reacquaintance with familiar objects.

Some museums have a reasonable policy of not permitting flash photography, since the bright light of camera flashes can degrade the colors of paint and dyes. Others must insist on no photography when the objects on display are on loan from owners who will not permit reproductions of their images.

But in general, I object when museums and archives prohibit photography, especially when the aim is to force more visitors to come to the physical site. Most people the world over will never be able to visit the world's great museums. And many scholars could benefit from digital images of archival materials. During a recent visit to an archive that hosts many of Henry David Thoreau's papers, I was disappointed to learn that I would not be permitted to take photos of some of the papers I wanted to read later. This forces scholars to spend more time in the archive, which means spending more money - simply prohibitive for many of us. So I type, or scribble, as quickly as I can to transcribe texts in some archives, and hope that I can somehow find what I need in the time I have.

The Ballpoint As A Tool For Seeing

But what if what you want to remember is not a text but an image? Scott Parsons, a gifted artist and a friend of mine, has taught me that one need not be very talented with a pen to begin to capture images. As Dr. Cornelius said in one of Lewis's stories, "A scholar is never without [pen and paper]," and I've tried to make that my rule, too, carrying pen and paper with me everywhere. Scott tells me that a cheap ballpoint pen is, after all, one of the best tools for seeing.

It turns out, he's right: the pen is often mightier than the camera. I think this is because the camera captures all available light, while the pen only captures what my eye and hand tell it to. The chief obstacle to overcome is the disconnect between what my eye sees and what my hand draws. Scott has pointed out to me that this is not the fault of my hand so much as a problem of mistaking what I think I see for what I actually see. In other words, it is a problem of misdirected attention, when I pay attention to what I think is there rather than to what the light is actually doing.

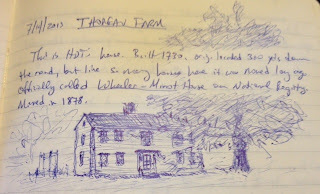

So far, no one in any museum has objected to my drawing what I see. In most cases, when I draw pictures, people seem honored that I should take the time. I drew this picture of the Thoreau homestead in Concord this summer, and a curator there happened to see it as I journaled. She seemed pleased that I took the time to try to draw it. I find that taking the time to draw helps me to notice details I'd have otherwise missed. You can see I'm not a great artist, little improved from my youth. But I'm not ashamed, because even if it's not a brilliant representation, it doesn't need to be; it is a record, in blue lines, of ten minutes of attention. The image is not a photograph; it is a symbol of memory, like a call number for a book in a library that helps me to recall quickly the time I spent sitting on the grass in Concord considering the place where Henry David grew up.

Memories Of Delight

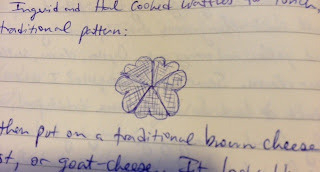

I've also begun drawing inside people's homes when I'm a guest there - always with permission, of course. This summer several kind Norwegian friends took me in for a week, giving me space to write while overlooking a fjord, and cooking me delicious Norwegian food. In the evening we built fires in the hearth and talked quietly or played cards. These are fond memories with friends, but they're also memories of delight in seeing new shapes of things. Norwegians build fires and eat waffles as we Americans do, but the fireplaces and the waffle irons are different from the ones I know from my home. The waffles I saw were all shaped like heart-flowers, giving visual delight in addition to the delightful taste (though I'm not yet sold on brown cheese as a topping.) The fireplaces I saw were all open on not just one side, but two. They looked different, but it was only when I began to draw them that I noticed what I was seeing. This is a small thing, perhaps, but it is a reminder that what I take to be the natural shape of things often has as much to do with the traditions I grew up with as with nature. As an aside, when I take the time to draw pictures, it often seems to be taken as a sign of respect, which is just how I intend it: this place you live in, this object in your home, is so wonderful to me that I wish to give it my attention and make it a permanent resident in my journal, the log-book of my heart. May I? Thank you, and thank you for the hospitality that allowed me to witness this.

Pics Or It Didn't Happen

Sometimes I choose not to take photos simply because the camera is itself a sign. When we hold it in front of our face, it becomes not just a lens through which we see, but a symbol of distance: this moment, this image, matters because it will matter somewhere else, somewhen else. There's nothing wrong with wanting to preserve the moment, but when the apparatus becomes the medium through which we perceive everything - when we feel we must record a photonic image of everything to make the moment real, reality itself somehow becomes less to us.

Icons As Luminous Doorways

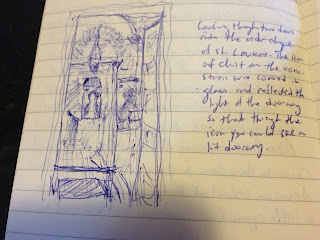

This summer I had the privilege of visiting the Monastery of Hosios (Saint) Loukas near Delphi in Greece. I'm not Orthodox, but I have real appreciation for what I learn from the Orthodox traditions. An Orthodox priest in my town has told me that icons are not objects of worship, but means of worship, images that help us to pray, just as windows help us to see. The pray-er who regards the icon isn't supposed to see the icon, but, as with windows, to see through the icon. In some sense the artistic image is intended to vanish when it is doing what it was intended to do. This language has been a little bit mysterious to me at times, but at the monastery this summer I had an illustrative experience: I stood in a doorway with bright sunlight shining behind me. Ahead, I could see through another doorway into the narthex of a chapel, and then through another doorway, to the altar at the far end. Beside every Orthodox altar there is an icon of Christ. This one was covered with glass, as icons often are. The glass reflected back to me the image of the doorway behind me, as though in the center of the image of Christ there were a luminous doorway. I tried to take a photo of this, but the contrasts were too great. So I took out my paper and pen and sketched what I saw. It's not a superb image, but it turned out far better than my photographic attempts did. And, as in other cases, I found myself feeling considerably more present and more respectful of the place.

The View From The Pew

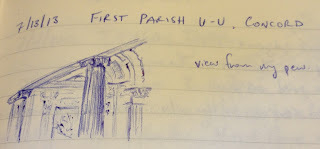

This was the case with several other holy sites I visited this summer as well. I had the privilege of hearing Robert Richardson lecture on Emerson in the Unitarian church in Concord, MA this summer, and then to visit the "African Meeting House" in Boston, a site of worship and of community activism for African Americans in the 19th century. It somehow didn't feel right to let the camera intrude into these places. The pen, by contrast, felt like an instrument properly reverent. Each stroke of the pen strengthening lines became like a prayer or an act of gratitude and reverence for the places I was in. In each case I sketched a "view from my pew," the view I had while sitting as worshipers have sat there in times past - and present.

No Photos!

But to return to the complaint with which I began this piece, too many places insist that no photography be allowed inside. While participating in a Summer Institute on Transcendentalism sponsored by the National Endowment for the Humanities this summer, I was able to visit some wonderful places, like the Thoreau Homestead, several of the homes of Louisa May Alcott, and Emerson's home. Visiting these places makes me a better teacher: they help me to tell a better story about the texts and ideas that emerged from them. Bronson Alcott, Louisa May's father, may have been odd, but his oddity is fascinating and delightful. He built this outbuilding to house his Concord School of Philosophy, for instance:

Architecture As The Embodiment Of Ideas

And he had some beautiful ideas about education: like the belief that children should be allowed to learn what they love to learn, that they should become bodily and sensorily engaged in their learning, that they should run and play and have recess, that art and literature should be significant in their learning, and so on. I knew these ideas before visiting his Concord home and Fruitlands, but seeing the buildings he built to house his ideas helps me to see how he envisioned those ideas at work.

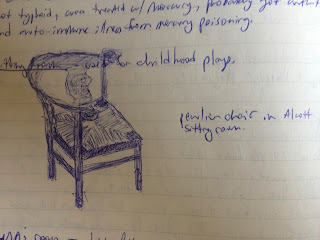

Unfortunately, I can only show you the outside of the buildings at the Alcott house, because there's no photography allowed inside, nor at the Emerson home either. So if you live far away, tant pis. I guess you'll have to just travel and visit it. Or, if you like, I can share the sketches I was able to make in our hurried tour. Yes, let's do that. I loved this chair, which is so oddly shaped. In a time when so many chairs seemed intended to make you sit ramrod straight, this one seems to invite you to slouch in different directions, to be at ease in your own body, to delight in sitting in the company of others:

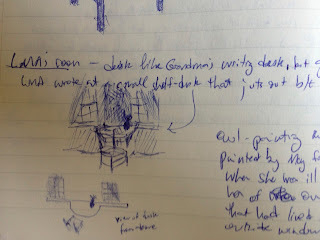

The Alcotts weren't wealthy, but Bronson and his wife managed to provide each of their children with a room of their own, and each of those rooms is suited to the disposition and arts of the child. Louisa May's room has a beautiful little half-moon shelf-desk jutting out between two large windows, perfect for writing stories and books, with excellent light. When I visited, the room was full of tourists, so a photo wouldn't have captured it anyway, and my drawing is very hasty and a little cramped itself, but here's a rough idea of what it looks like while standing beside her bed, plus an attempt to give the bird's-eye view:

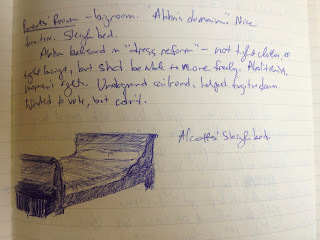

Bronson and his wife Abby had some lovely furniture, and I was especially captivated by their sleigh-bed. Its curved ends and gentle woodwork make the bed seem a place worth being, a place of rest and delight:

What I wish is that the owners and curators of these places would recognize that allowing visitors to take photos can help us to preserve the very places we are visiting, and to teach others about them. I understand the desire to make those places special, just as I understand the fear that if you allow images to be taken maybe fewer visitors will come. But for us teachers, taking pictures can be a way to allow our students to visit a place they might otherwise never go.

Thankfully, no one has yet prohibited my pen and paper. Or yours. I'm not up to Urban Sketchers quality, and may never be, but I'm not ashamed to use my pen as a visual instrument, nor to share with you what I've seen through it. And I hope you'll do the same.

Rebel Without A Camera: Museums, Images, and Memory

|

| My old Brownie. No flash! |

As a kid I found most museums boring, but now I really appreciate and enjoy them. I've spent many days of my life in the British Museum and in several museums in Athens, and each time I'm there I feel that time is rewarded with fresh discoveries and with reacquaintance with familiar objects.

Some museums have a reasonable policy of not permitting flash photography, since the bright light of camera flashes can degrade the colors of paint and dyes. Others must insist on no photography when the objects on display are on loan from owners who will not permit reproductions of their images.

But in general, I object when museums and archives prohibit photography, especially when the aim is to force more visitors to come to the physical site. Most people the world over will never be able to visit the world's great museums. And many scholars could benefit from digital images of archival materials. During a recent visit to an archive that hosts many of Henry David Thoreau's papers, I was disappointed to learn that I would not be permitted to take photos of some of the papers I wanted to read later. This forces scholars to spend more time in the archive, which means spending more money - simply prohibitive for many of us. So I type, or scribble, as quickly as I can to transcribe texts in some archives, and hope that I can somehow find what I need in the time I have.

The Ballpoint As A Tool For Seeing

But what if what you want to remember is not a text but an image? Scott Parsons, a gifted artist and a friend of mine, has taught me that one need not be very talented with a pen to begin to capture images. As Dr. Cornelius said in one of Lewis's stories, "A scholar is never without [pen and paper]," and I've tried to make that my rule, too, carrying pen and paper with me everywhere. Scott tells me that a cheap ballpoint pen is, after all, one of the best tools for seeing.

It turns out, he's right: the pen is often mightier than the camera. I think this is because the camera captures all available light, while the pen only captures what my eye and hand tell it to. The chief obstacle to overcome is the disconnect between what my eye sees and what my hand draws. Scott has pointed out to me that this is not the fault of my hand so much as a problem of mistaking what I think I see for what I actually see. In other words, it is a problem of misdirected attention, when I pay attention to what I think is there rather than to what the light is actually doing.

|

| Thoreau Farm |

|

| Norwegian waffle: a bouquet of hearts |

|

| Norwegian fireplace |

I've also begun drawing inside people's homes when I'm a guest there - always with permission, of course. This summer several kind Norwegian friends took me in for a week, giving me space to write while overlooking a fjord, and cooking me delicious Norwegian food. In the evening we built fires in the hearth and talked quietly or played cards. These are fond memories with friends, but they're also memories of delight in seeing new shapes of things. Norwegians build fires and eat waffles as we Americans do, but the fireplaces and the waffle irons are different from the ones I know from my home. The waffles I saw were all shaped like heart-flowers, giving visual delight in addition to the delightful taste (though I'm not yet sold on brown cheese as a topping.) The fireplaces I saw were all open on not just one side, but two. They looked different, but it was only when I began to draw them that I noticed what I was seeing. This is a small thing, perhaps, but it is a reminder that what I take to be the natural shape of things often has as much to do with the traditions I grew up with as with nature. As an aside, when I take the time to draw pictures, it often seems to be taken as a sign of respect, which is just how I intend it: this place you live in, this object in your home, is so wonderful to me that I wish to give it my attention and make it a permanent resident in my journal, the log-book of my heart. May I? Thank you, and thank you for the hospitality that allowed me to witness this.

Pics Or It Didn't Happen

Sometimes I choose not to take photos simply because the camera is itself a sign. When we hold it in front of our face, it becomes not just a lens through which we see, but a symbol of distance: this moment, this image, matters because it will matter somewhere else, somewhen else. There's nothing wrong with wanting to preserve the moment, but when the apparatus becomes the medium through which we perceive everything - when we feel we must record a photonic image of everything to make the moment real, reality itself somehow becomes less to us.

|

| Ecce: the heart of Christ, a luminous doorway |

This summer I had the privilege of visiting the Monastery of Hosios (Saint) Loukas near Delphi in Greece. I'm not Orthodox, but I have real appreciation for what I learn from the Orthodox traditions. An Orthodox priest in my town has told me that icons are not objects of worship, but means of worship, images that help us to pray, just as windows help us to see. The pray-er who regards the icon isn't supposed to see the icon, but, as with windows, to see through the icon. In some sense the artistic image is intended to vanish when it is doing what it was intended to do. This language has been a little bit mysterious to me at times, but at the monastery this summer I had an illustrative experience: I stood in a doorway with bright sunlight shining behind me. Ahead, I could see through another doorway into the narthex of a chapel, and then through another doorway, to the altar at the far end. Beside every Orthodox altar there is an icon of Christ. This one was covered with glass, as icons often are. The glass reflected back to me the image of the doorway behind me, as though in the center of the image of Christ there were a luminous doorway. I tried to take a photo of this, but the contrasts were too great. So I took out my paper and pen and sketched what I saw. It's not a superb image, but it turned out far better than my photographic attempts did. And, as in other cases, I found myself feeling considerably more present and more respectful of the place.

|

| First Parish, Concord, Mass. |

|

| African Meeting House, Boston, Mass. |

This was the case with several other holy sites I visited this summer as well. I had the privilege of hearing Robert Richardson lecture on Emerson in the Unitarian church in Concord, MA this summer, and then to visit the "African Meeting House" in Boston, a site of worship and of community activism for African Americans in the 19th century. It somehow didn't feel right to let the camera intrude into these places. The pen, by contrast, felt like an instrument properly reverent. Each stroke of the pen strengthening lines became like a prayer or an act of gratitude and reverence for the places I was in. In each case I sketched a "view from my pew," the view I had while sitting as worshipers have sat there in times past - and present.

No Photos!

But to return to the complaint with which I began this piece, too many places insist that no photography be allowed inside. While participating in a Summer Institute on Transcendentalism sponsored by the National Endowment for the Humanities this summer, I was able to visit some wonderful places, like the Thoreau Homestead, several of the homes of Louisa May Alcott, and Emerson's home. Visiting these places makes me a better teacher: they help me to tell a better story about the texts and ideas that emerged from them. Bronson Alcott, Louisa May's father, may have been odd, but his oddity is fascinating and delightful. He built this outbuilding to house his Concord School of Philosophy, for instance:

|

| Alcott's Concord School of Philosophy, Orchard House |

And he had some beautiful ideas about education: like the belief that children should be allowed to learn what they love to learn, that they should become bodily and sensorily engaged in their learning, that they should run and play and have recess, that art and literature should be significant in their learning, and so on. I knew these ideas before visiting his Concord home and Fruitlands, but seeing the buildings he built to house his ideas helps me to see how he envisioned those ideas at work.

|

| Chair in the Orchard House |

|

| Louisa May Alcott's writing desk |

|

| The Alcotts' sleigh-bed |

What I wish is that the owners and curators of these places would recognize that allowing visitors to take photos can help us to preserve the very places we are visiting, and to teach others about them. I understand the desire to make those places special, just as I understand the fear that if you allow images to be taken maybe fewer visitors will come. But for us teachers, taking pictures can be a way to allow our students to visit a place they might otherwise never go.

Thankfully, no one has yet prohibited my pen and paper. Or yours. I'm not up to Urban Sketchers quality, and may never be, but I'm not ashamed to use my pen as a visual instrument, nor to share with you what I've seen through it. And I hope you'll do the same.

∞

Bless You!

What should you say when someone sneezes? I've been pondering this for years. Here are my reflections on that, by way of thinking about foreign-language pedagogy, and about what it means to bless someone:

The Emperor Charles V reportedly said that as many languages as a man knows, that many times over is he a man. I don't know if that's true, but in high school I took courage from it. I was athletic, but lean, with a great build for biking and running, but too slender to be considered dangerously manly. My only formal sports were swimming and ultimate frisbee. I loved skiing and hiking and rock-climbing, but the more I exercised, the leaner I got. There was no chance I'd ever become a star athlete, and I think that realization saved me from trying to become what I was not. Although I didn't know Emerson's writing back then, I nevertheless arrived at an Emersonian conclusion: there are as many kinds of manliness, and courage, as there are men and women to embody them. Emerson puts it like this:

This turns out to be a good way to learn one's own language, too. Not everything can be translated, and when you find something in your native tongue that's hard to say in another language, you've found something that is a unique possession of the speakers of your language. Or when you learn that one word in your language takes many forms in another language, you begin to see how your cultural heritage has come equipped with some blind spots. The same is true of grammar, of inflection, of syntax, and so on.

So learning another language is not simply a matter of replacing one vocabulary with another. Learning a language means learning a culture, a history, a literature.

(This is why language-learning software can help, but it's not enough, and it's no substitute for excellent teachers and for studying abroad.)

In middle school, as I was trying to actualize all my potential and to become as many men as I could be, I spent a lot of time learning basic phrases and grammar in other languages. How do you greet someone in this language? How do you say goodbye? How do you ask for what you want? These tend to be fairly straightforward in the languages I studied.

But some phrases were harder. How do you say "Please"? That word is, after all, a contraction of a whole clause, "If it please you," with a subjunctive verb. It's not like a name for an object or a place, which might be easily translated; it's a way of calling on a whole tradition of regarding the wishes of others as important - or at least, of pretending to honor those wishes. Now, most of the languages I studied had simple ways of saying "please," but along the way I discovered that not all English speakers consider "please" to be correct. Some religious communities, for instance, regard such words as unnecessary; we should be willing to give what we're asked for without demanding that the other regard our wishes as important, they reason.

Another phrase similarly exposed something about cultures: what do you say when someone sneezes? In many languages, the answer is that you say "Your health!" Many English speakers I know use the German Gesundheit without knowing that this is what they are saying, in another language. That's fascinating: we feel the need to say something, even if we don't know what the word means.

When I first met my frosh college roommate, Nick, he sneezed. I said the customary thing: "Bless you!" He looked at me oddly, and didn't say anything. Over the coming weeks, I repeated the phrase each time he sneezed. Finally, he asked me "Why do you keep saying that?" I realized I hadn't any better answer than to say that's what I heard others do. His question got me wondering why we acknowledge sneezes.

After all, we don't say something to accompany other bodily functions, do we? Is there a stock phrase for hiccups, or burps? For a rumbling belly? A cough? A yawn?

Over the years, it started to bother me that others felt the need to comment on my sneezes. When I ask people why they do it, I usually get some lame reply about how it's because long ago people believed that sneezes were a sign of some dangerous spiritual or physical ailment; or that it had to do with fear of the Black Plague; or that it was a response to the fear that sneezes were signs of demonic possession; and in any case, sneezes needed to be countered with blessings.

Okay, fine. I'll let the Middle Ages off the hook next time they bless my sneezing. But why do YOU do it? The answer seems to be cultural habit. It's not a necessity of nature, but something we've made ourselves do until we've forgotten why we do it. It's a thoughtless reflex, and I think this is what annoys me.

Now, after years of being a curmudgeon and a grouch about this, I'm starting to reconsider my objection to these responses to my sternutations. On the one hand, these blessings are thoughtless, and they demand a reply of "thank you" when frankly, I'm still recovering from a sneeze and would rather not say anything. On the other hand, perhaps we shouldn't want fewer blessings in our lives, but more of them, or at least more sincere ones.

As I think back over my life, I've received these blessings often from strangers on a bus or a subway, or in a park in a foreign city. People who do not know me stop their activity to speak a word of blessing into my life, to look me in the eye and put into simple words their wishes for my good health.

Speaking does not make things so, not instantly, anyway. But putting things into words is nevertheless very powerful. I'm not talking magic here; I'm talking about the way our words affect ourselves and others. Naming is powerful. When our inarticulate anger or frustration evolves into naming someone as the one who needs to be punished, the person becomes a criminal, something less than a person. The greater the crime, the lesser the human. Because naming is powerful, cursing is powerful. Which is why I taught my kids that it's not words that are bad, but the uses of words.

And if history teaches us anything at all, it shows us how easy we find it to curse others, to come up with simple, curt, dehumanizing names for entire classes of others. We find it easy not to look others in the eye but to look no further than the skin, or to look through others as though they were not there. We find it easy to curse those who live across borders of towns and nations, those who drive in front of us or behind us, those whose faces we never see and whom we know only through a few words we've read online.

In light of that, I suppose that if you want to bless me--indeed, if you find it hard not to bless me--that should be a welcome thing. Just give me a minute to recover from my sneeze before I thank you. And may you be blessed, too.

The Emperor Charles V reportedly said that as many languages as a man knows, that many times over is he a man. I don't know if that's true, but in high school I took courage from it. I was athletic, but lean, with a great build for biking and running, but too slender to be considered dangerously manly. My only formal sports were swimming and ultimate frisbee. I loved skiing and hiking and rock-climbing, but the more I exercised, the leaner I got. There was no chance I'd ever become a star athlete, and I think that realization saved me from trying to become what I was not. Although I didn't know Emerson's writing back then, I nevertheless arrived at an Emersonian conclusion: there are as many kinds of manliness, and courage, as there are men and women to embody them. Emerson puts it like this:

“It is he only who has labor, and the spirit to labor, because courage sees: he is brave, because he sees the omnipotence of that which inspires him. The speculative man, the scholar, is the right hero. Is there only one courage, and one warfare? I cannot manage sword and rifle; can I not therefore be brave? I thought there were as many courages as men. Is an armed man the only hero? Is a man only the breech of a gun, or the hasp of a bowie-knife? Men of thought fail in fighting down malignity, because they wear other armour than their own.”So I threw myself into doing what I was made to do with joy, and to living a brave life in my own way. Some people find learning a foreign language terrifying; I do not. I'm one of those people blessed with an unusual ability to learn foreign languages quickly and with little effort. When I'm around a new language, I listen to its music and its rhythms and make them my own, and I begin to take apart the language as I hear it, so I can think with it, and watch its parts move. And I ask a lot of questions: How do you say this in your language? What does this mean? When do you say that?– R.W. Emerson, Commencement Address given at Middlebury College on July 22, 1845, in Emerson At Middlebury College, Robert Buckeye, ed. (Middlebury, Vermont: Friends of the Middlebury College Library, 1999), p. 39.

This turns out to be a good way to learn one's own language, too. Not everything can be translated, and when you find something in your native tongue that's hard to say in another language, you've found something that is a unique possession of the speakers of your language. Or when you learn that one word in your language takes many forms in another language, you begin to see how your cultural heritage has come equipped with some blind spots. The same is true of grammar, of inflection, of syntax, and so on.

So learning another language is not simply a matter of replacing one vocabulary with another. Learning a language means learning a culture, a history, a literature.

(This is why language-learning software can help, but it's not enough, and it's no substitute for excellent teachers and for studying abroad.)

In middle school, as I was trying to actualize all my potential and to become as many men as I could be, I spent a lot of time learning basic phrases and grammar in other languages. How do you greet someone in this language? How do you say goodbye? How do you ask for what you want? These tend to be fairly straightforward in the languages I studied.

But some phrases were harder. How do you say "Please"? That word is, after all, a contraction of a whole clause, "If it please you," with a subjunctive verb. It's not like a name for an object or a place, which might be easily translated; it's a way of calling on a whole tradition of regarding the wishes of others as important - or at least, of pretending to honor those wishes. Now, most of the languages I studied had simple ways of saying "please," but along the way I discovered that not all English speakers consider "please" to be correct. Some religious communities, for instance, regard such words as unnecessary; we should be willing to give what we're asked for without demanding that the other regard our wishes as important, they reason.

|

| Modern saints at Westminster Abbey; Their stories are a blessing. |

When I first met my frosh college roommate, Nick, he sneezed. I said the customary thing: "Bless you!" He looked at me oddly, and didn't say anything. Over the coming weeks, I repeated the phrase each time he sneezed. Finally, he asked me "Why do you keep saying that?" I realized I hadn't any better answer than to say that's what I heard others do. His question got me wondering why we acknowledge sneezes.

After all, we don't say something to accompany other bodily functions, do we? Is there a stock phrase for hiccups, or burps? For a rumbling belly? A cough? A yawn?

Over the years, it started to bother me that others felt the need to comment on my sneezes. When I ask people why they do it, I usually get some lame reply about how it's because long ago people believed that sneezes were a sign of some dangerous spiritual or physical ailment; or that it had to do with fear of the Black Plague; or that it was a response to the fear that sneezes were signs of demonic possession; and in any case, sneezes needed to be countered with blessings.

Okay, fine. I'll let the Middle Ages off the hook next time they bless my sneezing. But why do YOU do it? The answer seems to be cultural habit. It's not a necessity of nature, but something we've made ourselves do until we've forgotten why we do it. It's a thoughtless reflex, and I think this is what annoys me.

Now, after years of being a curmudgeon and a grouch about this, I'm starting to reconsider my objection to these responses to my sternutations. On the one hand, these blessings are thoughtless, and they demand a reply of "thank you" when frankly, I'm still recovering from a sneeze and would rather not say anything. On the other hand, perhaps we shouldn't want fewer blessings in our lives, but more of them, or at least more sincere ones.

As I think back over my life, I've received these blessings often from strangers on a bus or a subway, or in a park in a foreign city. People who do not know me stop their activity to speak a word of blessing into my life, to look me in the eye and put into simple words their wishes for my good health.

Speaking does not make things so, not instantly, anyway. But putting things into words is nevertheless very powerful. I'm not talking magic here; I'm talking about the way our words affect ourselves and others. Naming is powerful. When our inarticulate anger or frustration evolves into naming someone as the one who needs to be punished, the person becomes a criminal, something less than a person. The greater the crime, the lesser the human. Because naming is powerful, cursing is powerful. Which is why I taught my kids that it's not words that are bad, but the uses of words.

And if history teaches us anything at all, it shows us how easy we find it to curse others, to come up with simple, curt, dehumanizing names for entire classes of others. We find it easy not to look others in the eye but to look no further than the skin, or to look through others as though they were not there. We find it easy to curse those who live across borders of towns and nations, those who drive in front of us or behind us, those whose faces we never see and whom we know only through a few words we've read online.

In light of that, I suppose that if you want to bless me--indeed, if you find it hard not to bless me--that should be a welcome thing. Just give me a minute to recover from my sneeze before I thank you. And may you be blessed, too.

∞

Matt and I stand thigh-deep in one of the small streams that

tumble down the eastern slopes of the Green Mountains. Many of those

streams, including this one, have carved steep gorges over the

millennia. As the water falls it strips away the sand and loam, leaving

a course choked with jumbled boulders.

Matt and I stand thigh-deep in one of the small streams that

tumble down the eastern slopes of the Green Mountains. Many of those

streams, including this one, have carved steep gorges over the

millennia. As the water falls it strips away the sand and loam, leaving

a course choked with jumbled boulders.

Every year a few more trees, undercut by the current, tip over into the stream, where they lodge against the boulders and form temporary dams. As the water flows over those dams it digs deep plunge pools, bubbling and swirling for a few feet, then quickly settling into swift, clear, tea-colored glassy pools. The water slows only long enough to catch its breath before it plunges again, stair-stepping down the mountain, moving the mountain itself downstream one grain of sand at a time.

Beside us, logs carpeted in moss play host to uncounted lives of plants and animals. Trees reach their branches down into the cleft cut by the river, searching for sunlight wherever they can in this steep gorge. Small flies whirl restlessly across our vision. Their blue wings and olive bodies seem an unnecessary and extravagant dash of color on something so small, so ephemeral.

Vermont is named for the greenness of its mountains, or les monts verts as the first French settlers called these ancient hills. One of the rivers nearby is called the Lemon Fair, its name preserving the French sounds in misplaced English words. A sweeping glance would call this place green, but it only takes a moment of slowing down to really look before you see all the rainbow represented here.

Much of the color is underwater, on the scales of the fine-featured trout that fin the current before us. The native brook trout are dappled a vermiculated green above, fading to pale bellies below. Their fins are slashed with bright red and white. The rainbow trout, imported from the west coast, iridesce when a beam of sunlight finds its way down through the leaves and the water. The young brown trout - far from their native Europe - shine like salmon. Under the rocks small tan sculpin harvest tiny invertebrate meals.

Gray stones slide slower than glaciers down the bank, moving imperceptibly and irresistibly toward the sea. On the bank, seven tiny mushrooms stand up, no taller than my thumb, their caps bright orange like yearling efts.

It is a perfect day. We are grateful to receive it, grateful to be here, to stand in these waters as their life flows around us.

*****

As I think of standing in the river, I am reminded of this passage from Thoreau:

“Late in the afternoon we passed a man on the shore fishing

with a long birch pole, its silvery bark left on, and a dog at his side, rowing

so near as to agitate his cork with our oars, and drive away luck for a season;

and when we had rowed a mile as straight as an arrow, with our faces turned

toward him, and the bubbles in our wake still visible on the tranquil surface,

there stood the fisher still with his dog, like statues under the other side of

the heavens, the only objects to relieve the eye in the extended meadow; and

there would he stand abiding his luck, till he took his way home through the

fields at evening with his fish. Thus, by one bait or another, Nature

allures inhabitants into all her recesses [….] His fishing was not a sport,

nor solely a means of subsistence, but a sort of solemn sacrament and

withdrawal from the world, just as the aged read their Bibles." H.D. Thoreau, A Week On The Concord And Merrimack Rivers, (New York: Signet, 1961; emphasis mine)

p. 31-32.

Green Mountain Creek

Matt and I stand thigh-deep in one of the small streams that

tumble down the eastern slopes of the Green Mountains. Many of those

streams, including this one, have carved steep gorges over the

millennia. As the water falls it strips away the sand and loam, leaving

a course choked with jumbled boulders.

Matt and I stand thigh-deep in one of the small streams that

tumble down the eastern slopes of the Green Mountains. Many of those

streams, including this one, have carved steep gorges over the

millennia. As the water falls it strips away the sand and loam, leaving

a course choked with jumbled boulders.Every year a few more trees, undercut by the current, tip over into the stream, where they lodge against the boulders and form temporary dams. As the water flows over those dams it digs deep plunge pools, bubbling and swirling for a few feet, then quickly settling into swift, clear, tea-colored glassy pools. The water slows only long enough to catch its breath before it plunges again, stair-stepping down the mountain, moving the mountain itself downstream one grain of sand at a time.

Beside us, logs carpeted in moss play host to uncounted lives of plants and animals. Trees reach their branches down into the cleft cut by the river, searching for sunlight wherever they can in this steep gorge. Small flies whirl restlessly across our vision. Their blue wings and olive bodies seem an unnecessary and extravagant dash of color on something so small, so ephemeral.

Vermont is named for the greenness of its mountains, or les monts verts as the first French settlers called these ancient hills. One of the rivers nearby is called the Lemon Fair, its name preserving the French sounds in misplaced English words. A sweeping glance would call this place green, but it only takes a moment of slowing down to really look before you see all the rainbow represented here.

Much of the color is underwater, on the scales of the fine-featured trout that fin the current before us. The native brook trout are dappled a vermiculated green above, fading to pale bellies below. Their fins are slashed with bright red and white. The rainbow trout, imported from the west coast, iridesce when a beam of sunlight finds its way down through the leaves and the water. The young brown trout - far from their native Europe - shine like salmon. Under the rocks small tan sculpin harvest tiny invertebrate meals.

Gray stones slide slower than glaciers down the bank, moving imperceptibly and irresistibly toward the sea. On the bank, seven tiny mushrooms stand up, no taller than my thumb, their caps bright orange like yearling efts.

It is a perfect day. We are grateful to receive it, grateful to be here, to stand in these waters as their life flows around us.

*****

|

| My friends Bill and Brian paddle the Concord River, as Thoreau once did. |

*****

*****

Note: I think Matt intended his gesture of catching water in fun, but I like

the way it looks like a gesture of gratefully receiving the waterfall.

I'm also reminded of a sentence I recently read in Stephanie Mills' book, Epicurean Simplicity:

“[F]ishers can be natural historians and waterside contemplatives par excellence."

By “fishers” she means those who fish,

fishermen and fisherwomen and fisherchildren. This comes at the conclusion of a story in which she almost

reprimanded a small boy who was catching fish for bait, but then decided not to

do so. She was afraid he was catching too many, or juvenile fish that would not grow to maturity. Later, she considered the

fact that if he was fishing, he could well be learning about fish in a way no

one else does. She reports that she was glad she didn't reprimand him.

It's true that in hunting and fishing some people learn practices of cruelty towards animals, or learn to regard animals instrumentally; but my experience is that most of the people I know who hunt and fish know a lot more about nature than the average person who does not. Harvesting wild food often makes people naturalists, and can indeed make us much more "mindful carnivores" as Tovar Cerulli puts it.

Anecdotally, I find that hunting and fishing have made me less of a carnivore, and increasingly concerned with animal flourishing. (The quote from Stephanie Mills is found in Epicurean Simplicity, published in Washington, Covelo, and London: Island Press/Shearwater Books, 2002 p.125.)

*****

∞

Three Words About Writing: Plato, Emerson, Bugbee

Last weekend I was at a small writing conference in Vermont, where I was asked to give a meditation on writing with a love of wisdom. Although I'm a philosophy professor, I'm not sure I have a bead on loving wisdom yet.

(To paraphrase Thoreau, there are nowadays plenty of philosophy professors, but not so many lovers of wisdom.)

Instead, I offered a reflection on three ideas that matter for me as I write. Here are three that I keep coming back to:

First, a word from Plato: "Follow the argument wherever it leads." And try to find good interlocutors. If you surround yourself with people who say "yes" to everything you say, your writing and your thinking will both atrophy. If the trail leads uphill, it's no good to stay on the level path. Plato seems to have used writing as a way of sketching out how one might begin to solve problems. He didn't give answers so much as good questions. His dialogues survive because they are such good invitations for us to try to work out the solutions ourselves.

Second, Emerson: Your journals are your savings accounts. Your life is the way you earn deposits. "If it were only for a vocabulary the scholar would be covetous of action," he wrote. "Life is our dictionary." Without action, there is no experience; and without experience, the writer's vocabulary becomes continually narrower. Emerson wrote in fragments - very short essays, or sentences - in his journals, and when he sat down to write his essays and lectures, he found those fragments to be a rich vein of inspiration and even of finished work.

Finally, Bugbee: "Get it down." Write forward; don't edit too much. Keep writing, and as much as possible, write the way it comes. Attend to experience as it is given, without trying too hard to color it or shape it. Practice seeing, and seeing honestly, and write what you see.

This isn't by any means a whole course in writing, but it is a place to start. And often, that's what writers need: to start.

Then keep writing.

(To paraphrase Thoreau, there are nowadays plenty of philosophy professors, but not so many lovers of wisdom.)

Instead, I offered a reflection on three ideas that matter for me as I write. Here are three that I keep coming back to:

First, a word from Plato: "Follow the argument wherever it leads." And try to find good interlocutors. If you surround yourself with people who say "yes" to everything you say, your writing and your thinking will both atrophy. If the trail leads uphill, it's no good to stay on the level path. Plato seems to have used writing as a way of sketching out how one might begin to solve problems. He didn't give answers so much as good questions. His dialogues survive because they are such good invitations for us to try to work out the solutions ourselves.

Second, Emerson: Your journals are your savings accounts. Your life is the way you earn deposits. "If it were only for a vocabulary the scholar would be covetous of action," he wrote. "Life is our dictionary." Without action, there is no experience; and without experience, the writer's vocabulary becomes continually narrower. Emerson wrote in fragments - very short essays, or sentences - in his journals, and when he sat down to write his essays and lectures, he found those fragments to be a rich vein of inspiration and even of finished work.

Finally, Bugbee: "Get it down." Write forward; don't edit too much. Keep writing, and as much as possible, write the way it comes. Attend to experience as it is given, without trying too hard to color it or shape it. Practice seeing, and seeing honestly, and write what you see.

This isn't by any means a whole course in writing, but it is a place to start. And often, that's what writers need: to start.

Then keep writing.

∞

"Life Is Our Dictionary"

"Authors we have in numbers, who have written out their vein, and who, moved by a commendable prudence, set sail for Greece or Palestine, follow the trapper into the prairie, or ramble round Algiers to replenish their merchantable stock. If it were only for a vocabulary the scholar would be covetous of action. Life is our dictionary."

R.W. Emerson, "The American Scholar"

∞

A Republic Without Education

“In a republic education is indispensable. A republic without education is like

the creature of imagination, a human being without a soul, living and moving

blindly, with no just sense of the present or the future. It is a monster.”

Charles Sumner, Massachusetts Senator, in “Reconstruction Again: The Ballot and Public Schools Open to All,” speeches in the Senate, on the Supplementary Reconstruction Bill, March 15 and 16, 1867. TheWorks of Charles Sumner, Vol XI, (Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1875) p. 156

∞

Armed in Anxiety

My article on guns, fear, and virtue ethics, now accessible at The Chronicle of Higher Education:

What do guns do for us? Many opponents of new gun legislation argue that they make us safer. Proponents of gun control hope to promote public safety by keeping guns out of the hands of bent young men who worship projectile power and senseless death. Most of our public-policy debates about guns have focused on safety, but in my opinion, not enough has been said about whether guns make us sound.Read the rest here.

Our word "safe" has roots in the Latin word salvus, which means not just "secure from harm" but "whole, well, and thriving"—that is to say, sound. This is one of philosophy's oldest concerns, to examine and foster this kind of sound, flourishing human life. This question is at the heart of Aristotle's ethics, for example. The opening lines of his Nicomachean Ethics declare that it is possible to regard life as having a kind of excellence, a sense of human flourishing and wholeness to which all of our sciences contribute. As Aristotle puts it, failure to reflect on this will make us like people who shoot without considering their target. (Yes, he really says that.)....

∞

What I Wish Penn State Would Do

Today Penn State, where I did some of my graduate studies, announced that they would begin making settlement offers to the victims of Jerry Sandusky's sexual assaults against children.

Years ago I read a story in one of the Toronto newspapers - I have not been able to track it down again - wherein a catholic diocese in Canada was being sued by First Nations people who had suffered from abusive policies when they were students in diocesan schools.

The newspaper asked the bishop whether he was concerned about the cost of settling the lawsuits. He replied that if the diocese had to sell all of its property to bring healing to the victims, that was not too high a price to pay. He added "the church isn't buildings but people. In the end, all we need is a table, a cup, and some books - and we really don't even need those."

His attitude is the one I wish my alma mater would adopt. The cost of settling lawsuits may seem high, but when you know you are in the wrong and you know your sins have caused great harm to children, is any price too high to pay?

Because a university similarly shouldn't think of itself as buildings but as a college, a group of people who come together to read and study. And for that all we need are some tables, some books, and maybe a few cups. Not much more. Everything else should be things with which we would gladly part if, in so doing, we can bring healing to those we have harmed, and better become the people we ought to be.

Years ago I read a story in one of the Toronto newspapers - I have not been able to track it down again - wherein a catholic diocese in Canada was being sued by First Nations people who had suffered from abusive policies when they were students in diocesan schools.

The newspaper asked the bishop whether he was concerned about the cost of settling the lawsuits. He replied that if the diocese had to sell all of its property to bring healing to the victims, that was not too high a price to pay. He added "the church isn't buildings but people. In the end, all we need is a table, a cup, and some books - and we really don't even need those."

His attitude is the one I wish my alma mater would adopt. The cost of settling lawsuits may seem high, but when you know you are in the wrong and you know your sins have caused great harm to children, is any price too high to pay?

Because a university similarly shouldn't think of itself as buildings but as a college, a group of people who come together to read and study. And for that all we need are some tables, some books, and maybe a few cups. Not much more. Everything else should be things with which we would gladly part if, in so doing, we can bring healing to those we have harmed, and better become the people we ought to be.

∞

Newspapers in 1854

"[The reading and thinking] class has immensely increased. Owing to the

silent revolution which the newspaper has wrought, this class has come

in this country to take in all classes. Look into the morning

trains...with them, enters the car the humble priest of politics,

finance, philosophy, and religion in the shape of the newsboy....Two

pence a head his bread of knowledge costs, and instantly the entire

rectangular assembly, fresh from their breakfast, are bending as one man

to their second breakfast."

R.W. Emerson, 1854.

∞

Co-authorship in the Humanities

My friend and co-author John Kaag has just published this piece in today's New York Times.

I think John is right on the money: there aren't firm rules about this, but many times we've both been warned that co-authorship in the humanities will be regarded as a sign of weakness, of not being able to carry one's own weight.

Maybe it's true. John and I both find that co-authorship make us better writers, so we must have been weak in some ways. But I don't see why we shouldn't therefore do even more writing with others.

I think John is right on the money: there aren't firm rules about this, but many times we've both been warned that co-authorship in the humanities will be regarded as a sign of weakness, of not being able to carry one's own weight.

Maybe it's true. John and I both find that co-authorship make us better writers, so we must have been weak in some ways. But I don't see why we shouldn't therefore do even more writing with others.

∞

Popper On The Gift Of Wonder

“My first thesis is that every philosophy, and especially every philosophical ‘school,’ is liable to degenerate in such a way that its problems become practically indistinguishable from pseudo-problems, and its cant, accordingly, practically indistinguishable from meaningless babble. This, I shall try to show, is a consequence of philosophical inbreeding. The degeneration of philosophical schools in its turn is the consequence of the mistaken belief that one can philosophize without having been compelled to philosophize by problems outside philosophy—in mathematics, for example, or in cosmology, or in politics or in religion, or in social life. In other words my first thesis is this: Genuine philosophical problems are always rooted in urgent problems outside philosophy and they die if these roots decay. In their efforts to solve them, philosophers are liable to pursue what looks like a philosophical method or technique or an unfailing key to philosophical success. But no such methods or techniques exist, in philosophy methods are unimportant, any method is legitimate if it leads to results capable of being rationally discussed. What matters is not methods or techniques but a sensitivity to problems, and a consuming passion for them, or, as the Greeks said, the gift of wonder.”

-- Karl Popper, “The Nature of Philosophical Problems,” in Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge. (Routledge, 2002) 95. (Boldface emphasis mine.)

-- Karl Popper, “The Nature of Philosophical Problems,” in Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge. (Routledge, 2002) 95. (Boldface emphasis mine.)

∞

Free Stone

One spring after heavy rains had come and gone, my father and I walked the banks of the Sawkill Creek. It was newly scrubbed by floodwaters that had gouged its banks, sweeping away trees, glacial deposit boulders, and even a few buildings as the Catskills shed the rainfall and shot it down to the Hudson.

The memory of that short walk remains one of the strongest from my childhood. The river had cut new banks, and had changed its own course. We walked along the round gravel banks and gazed up at the undercut roots of massive oaks and pines. We saw the bones of the earth laid bare by the river's irresistible blade. The river had cut itself a new bed. Everything in its path was destroyed; everything in its path was made new.

Since then I have walked hundreds of miles along - and often in - deep, clear waters over cobbled riverbeds. The sound of the water is the music of my soul, high sprinkled notes of splashing water and bass tones of massive stones rocking back and forth in the current. Walking in freestone streams makes me forget my worries, forget time itself.

The memory of that short walk remains one of the strongest from my childhood. The river had cut new banks, and had changed its own course. We walked along the round gravel banks and gazed up at the undercut roots of massive oaks and pines. We saw the bones of the earth laid bare by the river's irresistible blade. The river had cut itself a new bed. Everything in its path was destroyed; everything in its path was made new.

|

| Polished by the river. |

Since then I have walked hundreds of miles along - and often in - deep, clear waters over cobbled riverbeds. The sound of the water is the music of my soul, high sprinkled notes of splashing water and bass tones of massive stones rocking back and forth in the current. Walking in freestone streams makes me forget my worries, forget time itself.

∞

Mersenne, Education, and Intellectual "Property"

French cleric Marin Mersenne was the academic journal of his day. I have heard it said that in the seventeenth century the saying was "If you want to tell Europe, tell Mersenne."

Hobbes mentions Mersenne several times in his verse autobiography - high praise for a Roman Catholic cleric from someone whose antipathy for the Roman church and its philosophy was both deep and wide. But when Hobbes needed friends during his exile in France, Mersenne was glad to be one of those friends. Mersenne was a friend to all who were engaged in research. He was a living example of that idea of Justin Martyr's that Christians need not fear any books at all, since all the truth they contain belongs to the God who made and sustains it.

He was a friend to Galileo, and he passed Galileo's research on the regular oscillation of pendula along to Huygens in Holland, since he knew Huygens was trying to invent a more regular way of keeping time, leading to the invention of the pendulum clock. He corresponded with Pascal, Gassendi, and Descartes, and what he learned from one he shared with others who could use it.

In his Carnage and Culture, Victor Davis Hanson claims that one of the reasons for technological flourishing in the west is that western cultures treat knowledge as property that can be sold in the marketplace. I can't say whether Hanson's causal inference is correct, but his observation about intellectual "property" is acute.

But alongside it we should add another observation, namely that universities have long been places where ideas are exchanged freely. Yes, students pay tuition, but we also give free public lectures, allow free or inexpensive auditing, etc. What is being sold in the university is not the information but the cost of maintaining a place of intentional colloquy and pedagogy. We aren't selling ideas to students; we are allowing them to join us in the maintenance of a vital institution, and as members of that institution they participate in its life and share in its learning.

Mersenne was not a merchant of ideas but their curator, a steward ushering them to the places they were most needed. He was a gardener who made very few original contributions but who shared the best cultivars he could find with others in whose gardens they could flourish. His approach to knowledge was like that of the church in its earliest years, where "no one claimed private ownership of any possessions, but everything they owned was held in common" and goods were "distributed to each as they had need."

Mersenne's model is relevant to our contemporary conversations about the meaning and cost of an education, the value of universities, and the publication of scientific journals. Some money will be needed to maintain these institutions, but we should resist reducing them to market-based enterprises, or valuing their contributions in terms of revenues. There is also the shared work of curiosity, and of desiring to see our neighbors, and their ideas, flourish.

Hobbes mentions Mersenne several times in his verse autobiography - high praise for a Roman Catholic cleric from someone whose antipathy for the Roman church and its philosophy was both deep and wide. But when Hobbes needed friends during his exile in France, Mersenne was glad to be one of those friends. Mersenne was a friend to all who were engaged in research. He was a living example of that idea of Justin Martyr's that Christians need not fear any books at all, since all the truth they contain belongs to the God who made and sustains it.

He was a friend to Galileo, and he passed Galileo's research on the regular oscillation of pendula along to Huygens in Holland, since he knew Huygens was trying to invent a more regular way of keeping time, leading to the invention of the pendulum clock. He corresponded with Pascal, Gassendi, and Descartes, and what he learned from one he shared with others who could use it.

In his Carnage and Culture, Victor Davis Hanson claims that one of the reasons for technological flourishing in the west is that western cultures treat knowledge as property that can be sold in the marketplace. I can't say whether Hanson's causal inference is correct, but his observation about intellectual "property" is acute.

But alongside it we should add another observation, namely that universities have long been places where ideas are exchanged freely. Yes, students pay tuition, but we also give free public lectures, allow free or inexpensive auditing, etc. What is being sold in the university is not the information but the cost of maintaining a place of intentional colloquy and pedagogy. We aren't selling ideas to students; we are allowing them to join us in the maintenance of a vital institution, and as members of that institution they participate in its life and share in its learning.

Mersenne was not a merchant of ideas but their curator, a steward ushering them to the places they were most needed. He was a gardener who made very few original contributions but who shared the best cultivars he could find with others in whose gardens they could flourish. His approach to knowledge was like that of the church in its earliest years, where "no one claimed private ownership of any possessions, but everything they owned was held in common" and goods were "distributed to each as they had need."

Mersenne's model is relevant to our contemporary conversations about the meaning and cost of an education, the value of universities, and the publication of scientific journals. Some money will be needed to maintain these institutions, but we should resist reducing them to market-based enterprises, or valuing their contributions in terms of revenues. There is also the shared work of curiosity, and of desiring to see our neighbors, and their ideas, flourish.

∞

Light Perpetual

My friend Michael Foster died last night.

We knew it was coming. We saw it a long way off.

It still hurts like hell.

That's what this bereavement feels like: a little piece of hell. Our word "bereave" shares roots with "robbery," "rupture," and "interrupt." Something has been stolen from us, something has been broken, broken off. It should not be this way.

The words of Mark Heard's song "Treasure of the Broken Land" are going through my mind again and again:

The realization that he is gone keeps hitting me in waves. Now, as I write this, I keep having to stop as my throat constricts and my heart pounds, waiting for the tremor to pass through me, waiting for this wave of anguish to roll over me.

Maybe telling some of his story - our story - will help.

I met Mike when I was a grad student at Penn State. He was a professor at Penn State, and a sub-deacon at our church. (This means he helped with bread and wine, and looked good in a dress.) We both attended St Andrew's Episcopal Church in State College, and together we served on the vestry.

Sometime in my last year or two of grad work - I don't remember exactly; odd how the most important things can seem so commonplace - he invited me to go out to breakfast at the Corner Room. Like so many other kind professors I knew, he insisted on paying. (I now do the same with my students; the little things that mark our lives often become the lessons we really teach.)

Mike was trying to live the best life he could, using his scholarly discipline to love his neighbor, and trying to love his God to the best of his ability. He'd begun reading Dallas Willard's book The Divine Conspiracy, a book about becoming an intentional follower of Christ. I knew Willard's work on Husserl, and I guess Mike figured that made me a good conversation partner. We started meeting every week; he'd buy me breakfast and we'd talk about another chapter of Willard's book.

I didn't know what to make of Willard, and I was reading a lot of other books (this is the life of a grad student, after all) so the book didn't sink in much. But Mike's life did. Mostly we let the book lead us to talking about how we were living, and why we did what we did. Mike had studied economics, and recently his work had become really important to him as he discovered how to combine the methods of his discipline and of developmental psychology to advocate for poor children. His field was not mine, but I gathered that this was the upshot: a little money invested in children will pay dividends in their lives forever.

Mike was a restless soul, like Augustine, only finding his rest in God. I've lost count of how many times he and Mary and their four kids moved, but I know we've visited them in North Carolina and Alabama since we all left Pennsylvania. He wasn't afraid to pull up his stakes and move somewhere else if he thought he could do better work there. He has urged me, several times, to do the same, to be willing to regard tenure as a shackle rather than a privilege, and to move where the spirit moves me.

A few years ago Mike was diagnosed with a tumor in his brain. He approached this with the same doggedness he approached everything else. He poured himself into researching treatments, and flew all over the country seeking good medical advice. The tumor was removed at the cost of one of his eyes, and he went through some grueling radiation. (I long for the day when we will look back on our modern cancer treatments the way we now look back on bloodletting.) A little over a year ago he was at Mayo, not too far from me. I drove over to see him and Mary, and they gave me the gift of letting me pray for them. I say this is a gift, because I am at best a fumbling prayer, and they made me feel like a priest. They were suffering, and here they were, giving me this gift of unmerited affirmation.

Last summer a friend from Australia passed through Sioux Falls while enjoying a long service leave. He had rented a car and was driving from Seattle to Birmingham. I took advantage of my sabbatical and hopped in the car with him so I could visit Mike and Mary. They'd just moved to a new home, everything was in boxes, Mike's tumor was growing again, and yet they took me in and made me feel like I was long-lost family recently found again.

I loved talking with Mike, because his offhand observations were like gold. And the way he talked to people, and treated people, were always examples of both wit and grace. He was kind, and that allowed him to talk straight, to say with smiling integrity and southern charm, exactly what he was thinking. He was a true Israelite, in whom there wasn't much guile, and the guile that was there made him fun, and good company. I loved the way he loved his wife, and his kids. He wore that on the outside, not for show, but because his love was too big to keep on the inside. I'm sure it was flawed, as all loves are, but it was also intentional, the centerpiece of his life.

A couple of months ago, Mike asked if we could talk. You never know when the conversation you have will be the last one you ever have; this was ours. He told me the doctor had bad news: he might make it to Christmas, but not likely past that.

Mike asked me if he had lived right, if he had done the right thing. Yes, oh yes, Mike. I don't see as God sees, but I don't see how God could say otherwise. You made my life better. You loved well, in everything you did.

He also asked me if it was okay to ask God for healing. This one was harder to answer, but I decided that after thirteen years of benefiting from his straight talk, from free breakfasts and warm hospitality, I owed him nothing less than that. "It's okay to ask, Mike," I hesitated, not wanting to say it, not wanting to believe what would come next. I could hear in his conversation that he was declining, that his memory was being eaten away by the tumor. "But God's not required to answer those prayers. Miracles happen, but we call them miracles because they're rare. Christ died, and you and I will die too. It's time to start thinking about passing your work on to others."

His work was so good, too. He was at a new hinge-point, a pivot on which his research was ready to swing hard at injustice. He could see how ten more years of work - even two more years of work - would make a big difference. "I've got so much more to do; why is God taking me away now?" he asked. "I don't know, Mike. I just don't know."

Once again, as his last gift to me, he asked me to pray for him. It was hard to find the words, but I tried to talk to God the way Mike talked to me, letting Mike's life be a lesson in prayer. I don't like what you're doing, God. Make it better, make it right.

I suppose it is better for Mike not to be suffering, but Mike's death doesn't seem better, or right to me. I want him back, God. I know I can't have him back, not yet, but I miss him and it hurts.

If I cannot have him back, then give us this: a double portion of his spirit. The world is darker without him. I cannot see for the tears in my eyes; I cannot hear his voice anymore. I don't know how to pray. Give me his courage, and his wisdom, and his love. Let him be enshrined in me. Let all that was good in him live in my life now, and in the lives of his wife, his children, his students. Oh, this is the hard thing to ask: let us continue his work, with his spirit.

Mark Heard's words give me some hope:

Update: If you'd like to attend the memorial service on Wednesday, May 22, you may find details here. Mike asked that we wear bright colors, not black, to celebrate his life and to maintain our hope for the future.

We knew it was coming. We saw it a long way off.

It still hurts like hell.

That's what this bereavement feels like: a little piece of hell. Our word "bereave" shares roots with "robbery," "rupture," and "interrupt." Something has been stolen from us, something has been broken, broken off. It should not be this way.

The words of Mark Heard's song "Treasure of the Broken Land" are going through my mind again and again:

I thought our days were commonplaceI knew our days didn't number in the millions, but that's what my heart longed for, Mike. The loss hurts like hell because the time spent with you felt like heaven, like something that was meant to be eternal.

I thought they numbered in the millions

Now there's only the aftertaste

Of circumstance that can't pass this way again.

The realization that he is gone keeps hitting me in waves. Now, as I write this, I keep having to stop as my throat constricts and my heart pounds, waiting for the tremor to pass through me, waiting for this wave of anguish to roll over me.

Maybe telling some of his story - our story - will help.

I met Mike when I was a grad student at Penn State. He was a professor at Penn State, and a sub-deacon at our church. (This means he helped with bread and wine, and looked good in a dress.) We both attended St Andrew's Episcopal Church in State College, and together we served on the vestry.

Sometime in my last year or two of grad work - I don't remember exactly; odd how the most important things can seem so commonplace - he invited me to go out to breakfast at the Corner Room. Like so many other kind professors I knew, he insisted on paying. (I now do the same with my students; the little things that mark our lives often become the lessons we really teach.)

Mike was trying to live the best life he could, using his scholarly discipline to love his neighbor, and trying to love his God to the best of his ability. He'd begun reading Dallas Willard's book The Divine Conspiracy, a book about becoming an intentional follower of Christ. I knew Willard's work on Husserl, and I guess Mike figured that made me a good conversation partner. We started meeting every week; he'd buy me breakfast and we'd talk about another chapter of Willard's book.

I didn't know what to make of Willard, and I was reading a lot of other books (this is the life of a grad student, after all) so the book didn't sink in much. But Mike's life did. Mostly we let the book lead us to talking about how we were living, and why we did what we did. Mike had studied economics, and recently his work had become really important to him as he discovered how to combine the methods of his discipline and of developmental psychology to advocate for poor children. His field was not mine, but I gathered that this was the upshot: a little money invested in children will pay dividends in their lives forever.

|

| Mike and I stand together in the Dexter Ave King Memorial Church |

A few years ago Mike was diagnosed with a tumor in his brain. He approached this with the same doggedness he approached everything else. He poured himself into researching treatments, and flew all over the country seeking good medical advice. The tumor was removed at the cost of one of his eyes, and he went through some grueling radiation. (I long for the day when we will look back on our modern cancer treatments the way we now look back on bloodletting.) A little over a year ago he was at Mayo, not too far from me. I drove over to see him and Mary, and they gave me the gift of letting me pray for them. I say this is a gift, because I am at best a fumbling prayer, and they made me feel like a priest. They were suffering, and here they were, giving me this gift of unmerited affirmation.

Last summer a friend from Australia passed through Sioux Falls while enjoying a long service leave. He had rented a car and was driving from Seattle to Birmingham. I took advantage of my sabbatical and hopped in the car with him so I could visit Mike and Mary. They'd just moved to a new home, everything was in boxes, Mike's tumor was growing again, and yet they took me in and made me feel like I was long-lost family recently found again.

I loved talking with Mike, because his offhand observations were like gold. And the way he talked to people, and treated people, were always examples of both wit and grace. He was kind, and that allowed him to talk straight, to say with smiling integrity and southern charm, exactly what he was thinking. He was a true Israelite, in whom there wasn't much guile, and the guile that was there made him fun, and good company. I loved the way he loved his wife, and his kids. He wore that on the outside, not for show, but because his love was too big to keep on the inside. I'm sure it was flawed, as all loves are, but it was also intentional, the centerpiece of his life.

A couple of months ago, Mike asked if we could talk. You never know when the conversation you have will be the last one you ever have; this was ours. He told me the doctor had bad news: he might make it to Christmas, but not likely past that.

Mike asked me if he had lived right, if he had done the right thing. Yes, oh yes, Mike. I don't see as God sees, but I don't see how God could say otherwise. You made my life better. You loved well, in everything you did.

He also asked me if it was okay to ask God for healing. This one was harder to answer, but I decided that after thirteen years of benefiting from his straight talk, from free breakfasts and warm hospitality, I owed him nothing less than that. "It's okay to ask, Mike," I hesitated, not wanting to say it, not wanting to believe what would come next. I could hear in his conversation that he was declining, that his memory was being eaten away by the tumor. "But God's not required to answer those prayers. Miracles happen, but we call them miracles because they're rare. Christ died, and you and I will die too. It's time to start thinking about passing your work on to others."

His work was so good, too. He was at a new hinge-point, a pivot on which his research was ready to swing hard at injustice. He could see how ten more years of work - even two more years of work - would make a big difference. "I've got so much more to do; why is God taking me away now?" he asked. "I don't know, Mike. I just don't know."

Once again, as his last gift to me, he asked me to pray for him. It was hard to find the words, but I tried to talk to God the way Mike talked to me, letting Mike's life be a lesson in prayer. I don't like what you're doing, God. Make it better, make it right.

I suppose it is better for Mike not to be suffering, but Mike's death doesn't seem better, or right to me. I want him back, God. I know I can't have him back, not yet, but I miss him and it hurts.

If I cannot have him back, then give us this: a double portion of his spirit. The world is darker without him. I cannot see for the tears in my eyes; I cannot hear his voice anymore. I don't know how to pray. Give me his courage, and his wisdom, and his love. Let him be enshrined in me. Let all that was good in him live in my life now, and in the lives of his wife, his children, his students. Oh, this is the hard thing to ask: let us continue his work, with his spirit.

Mark Heard's words give me some hope:

I see you now and then in dreamsMay light perpetual shine upon you, Mike. May I see you, and hear you, in my dreams. May the light of Christ that shone in you while you were awake now shine in us while you sleep. And may we all awake to the same dawn, soon.

Your voice sounds like it used to

I believe I will hear it again

God, how I love you!

*****