The Sound of Philosophy

Last summer Travis Entenman and Lori Walsh interviewed me for their “Rivers and Rangelands” podcast.

They gave me a challenge: find a soundscape that matches the topic of our conversation.

So that’s what I did. Here’s a link to the podcast, or you can find it in all the usual places.

The location will remain a secret, but if you listen to the end of the podcast we sit without speaking for five minutes (really!) so you can hear where we are.

Academic philosophy can be drily heard in lecture halls and at conferences. But sometimes philosophy sounds like birdsong in a prairie riverbottom, with the wind brushing the tops of the cottonwoods.

Enjoy!

Buy My Books, Please

In an act of shameless self-promotion I’ll let you know that if you want to read my best nature writing (so far) my publisher has it on sale until November 30th. Half price and free shipping with the code CONFSHIP (they set that up for some recent academic conferences because we academics buy a lot of books and cannot resist a sale.)

Obviously this makes a great holiday gift for your friends and family. It also encourages the author to keep writing!

Here it is, my book on brook trout, fly-fishing, and conservation: It’s called Downstream, because we all live downstream.

Here, as a freebie, is a photo of a little brook trout I snapped underwater in Vermont two summers ago.

For all my life I have loved rivers and streams. I tromped in them as a boy, flipping over rocks, diving into deep pools, and searching for the delights that clean water carries downstream. For the last twenty years I’ve made research trips and taught classes alongside rivers and lakes and in the ocean, from my native Appalachians to North Africa, Arctic Alaska, and Central and South America. Everywhere I go I ask questions about the fish that live in the water, and all the multitude of lives that are intimately connected to them.

I’ve published several books but this one is probably my favorite. I’ve got another in the works right now that will appear in print next spring, on philosophy and camping. I’ve got some sketches and drafts of a half dozen other books as well. It’s fun to write them and even more fun to see them in print.

I hope you enjoy this book while I work on the next ones!

How To Live Well

Students in my “How To Live Well” class have been presenting their reflections to one another and it has been a wonderful experience for me as a teacher.

Together we read all of Plato’s Republic and Augustine’s Confessions slowly, with lots of conversation and writing reflections.

Now they’ve all written their final reflections and then giving a report on them to their classmates.

They’re telling the stories of their lives so far, and also telling the hopes they have for the years ahead. And then they’re giving each other kind and helpful questions and affirmations.

I think they’re discovering, in various ways, that they’re not alone in feeling as they do about life’s uncertainties. Many of them have come to embrace religious faith in recent years, and are exploring what that means for them as adults.

All semester I’ve wondered: why do they keep coming to class? I’ve had amazing attendance in that class. I don’t give quizzes, the homework is fairly minimal (read the book, come to class to discuss it, write reflections). And the exams are discussions.

My hunch is that they are glad not to have busywork, they’re glad to read a couple of great books closely, and they’re glad to have a chance to slow down and take their own lives seriously. A few have hinted at these things in their reports, anyway.

What I know: I take the students–and their lives–seriously. And I’m glad to see them coming to class, reading these books, and discussing big ideas that might help them to live well with others.

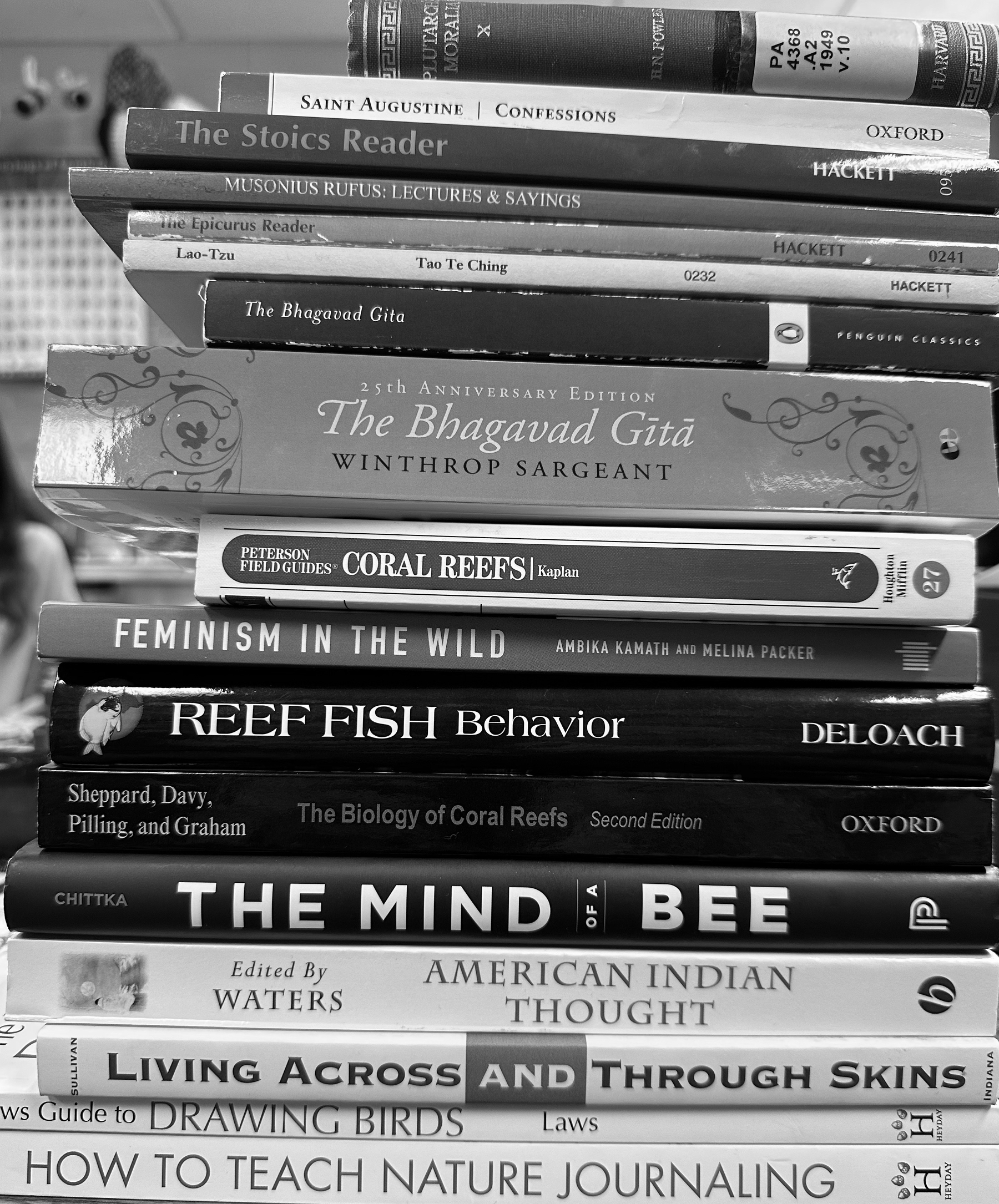

Today's Shelfies

Today’s shelfies. Fewer conversations with students, deeper reading.

Good books make good company and good conversation.

Tessellation

Casablanca

Looking up

Academy, Business, Charity, Mission

It was a college class on religion that taught me about the history of academia in the United States. Prof. Ferm walked us through why schools like Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and Dartmouth were founded, and what decisions they made as they grew.

Over my lifetime those lessons have come back to me often as I’ve considered the life cycles of other institutions of higher education. One of the big themes: many schools begin with a lofty vision of being a community, a “city on a hill,” an institution with a mission to serve the people of the region, a commitment to a creed and its advancement, etc.

And then, over time, they decide that the way to achieve longevity as institutions is to think of themselves as businesses. Which so often leads them to an awkward attempt to marry a business mindset with an eleemosynary or non-profit vision. And failing at both.

To be good at a business requires a sense of distinctiveness, a business proposition that makes one’s product the right choice. But when schools depend on similar sources of funding, accreditation, and assessment, the pressure to conform to competitors outweighs the drive to distinctiveness.

To be good at being a community built on a mission requires the community to be ever mindful of that mission, and to let it guide (at least at the macro level, if not at the micro level as well) major decisions. Fidelity to that mission might even run counter to balancing the books in the short term. It might require teaching donors why the mission matters rather than conforming the mission to the mission of donors. It might even mean telling accreditors what their standards are too low.

This is not an easy path to chart. A few schools divorce themselves from federal funding, but then find themselves in need of the funding of a few wealthy donors with their own missions. Some stick to their mission and find themselves living lives of poverty in order to keep the doors open. A rare few manage to continue to tell their own story to donors, and count on the alumni to believe strongly enough in what they experienced and gained to continue to fund it for those who come after.

I wish I had wisdom to say what a school should do. Instead I have charity enough to pray for those who must decide, and for those who will go through the education they provide, for those who might fund education through various means, and for those who will live with the consequences. Kyrie eleison.

Also reading Parker Palmer’s A Hidden Wholeness. I enjoyed his Let Your Life Speak, and am reading this one meditative as well. I appreciate the stories of academics who don’t fit neatly into academic life.

As a senior in college I started to read Middlemarch. I found back then that it was a book that wanted a reader who had time to enjoy it. College taught me to read fast, but not to read slowly, not to savor books. Now I am reading George Eliot slowly.

One of my students mentioned summitting Kilimajaro as a life goal in her term paper draft. I responded with a link to this documentary of my Middlebury classmate Chris Waddell, who summitted Kilimanjaro in an unusual and inspiring way.

Chance

In between editing chapters of my next book and commenting on student papers, I’m pondering the words “stochastic” and “tychism.”

Both have to do with randomness, chance, and hypothesis.

And those things make for some wonderful moments in life.

Next up: a private group discussion on the Peloponnesian War. We’ve been at this for over a year now, chiefly in primary texts. Such a good conversation.

Taught my students about Maimonides today and they had such good questions. Classes like that one really fill my sails.

Office Shelves and Optionality

A photo of part of my office.

My office is of course a place for me to do my work of teaching, scholarship, and service to the university.

It’s also a place where I serve tea to students as we talk about ideas both large and small.

And it’s a physical space that offers a glimpse of my story as a teacher, as a scholar, and as a person.

Often the space itself is a kind of lesson, and it becomes the beginning of conversations we did not plan.

I’m in a small city in the rural Upper Midwest, far from the coasts, far from the centers of power.

The students who come to my office hail from almost every state in my country, and from every populated continent. They come from big cities and rural ranches, wealthy suburbs and poor communities, and everything in between.

And so often when they first step into my office they say something like: wow.

Because many of them have never seen so many books, on so many topics, in so many languages.

Many have never had good tea, or good, open-ended conversation with a scholar who takes them seriously.

And I love the way this space fosters those conversations and maybe, just maybe, helps the students’ imaginations grow wider and richer.

Giraffe silhouette. Sioux Falls Zoo and Aquarium.

A fine place to walk with my son and his wife and my grandson yesterday.

Shelfie

Shelfie. (The books that come off my shelves while having conversations with students in my office.) This was after an hour or so of meeting with students. I reshelve at the end of the day.

Shelfies help me reflect on the day’s informal lessons, and of the fun I have teaching across multiple disciplines.

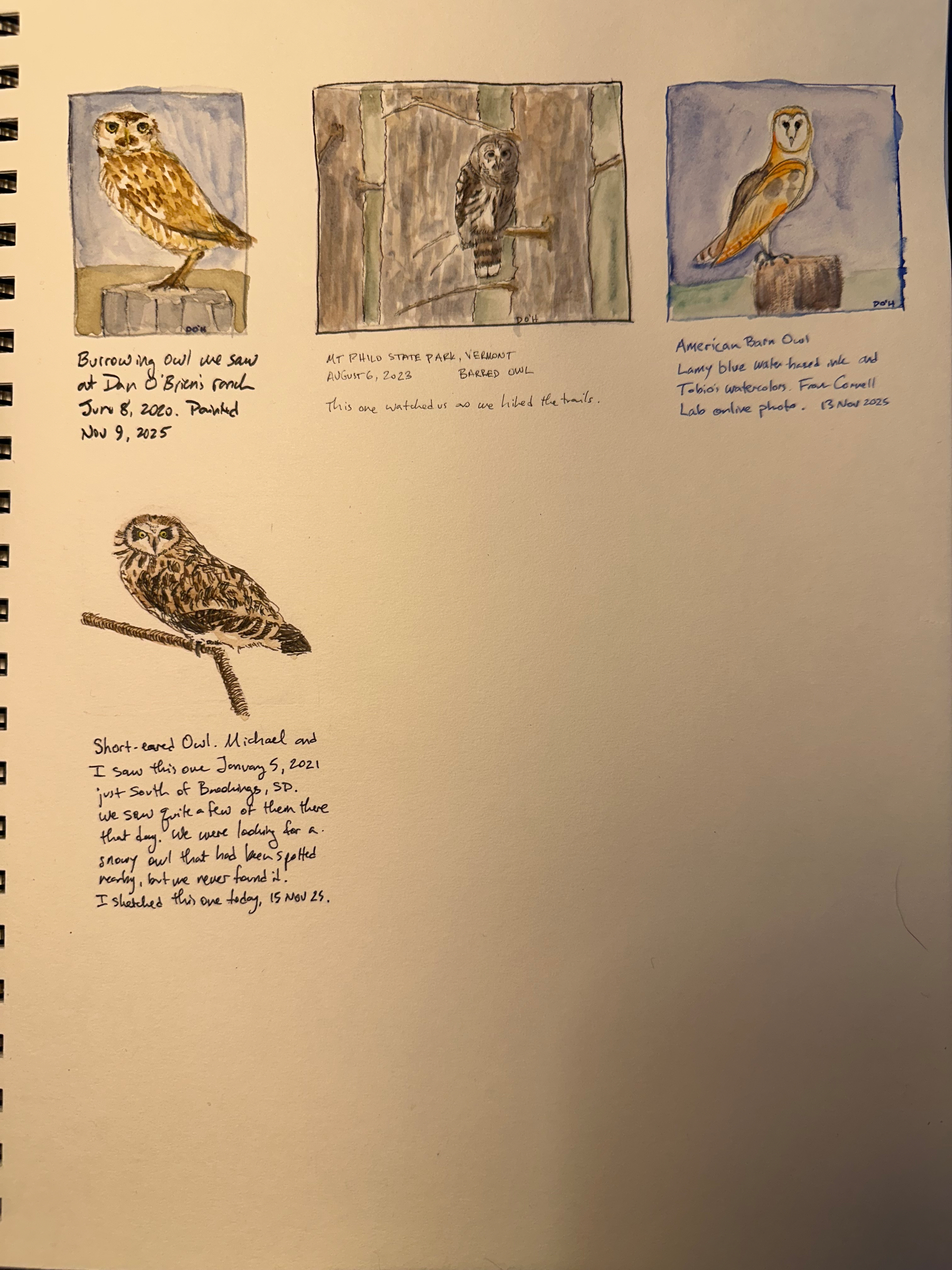

Sketching owls. This helps me know the owls better. Also having fun experimenting with different media.

The Kids Are Alright

Today I had one of the best days of teaching I’ve had in a long time. I’m worn out and poorer, but what a great day.

This morning the weather was warm and sunny so my environmental philosophy class met outside and many of the students had short sleeves even though it’s the middle of November. We try to meet outside every day, but some days are a challenge. Today we heard term paper presentations about parasitism, west African birds, and land rights. Each paper was thoughtful and thought-provoking, and it made me glad to sit there and listen as the students spoke.

Right after that I helped our Registrar with her FYS class' required service project. I spent hours this week cutting cedar planks to the right size and shape to make four Adirondack chairs. Today I brought all the lumber and a carload of tools and taught the students how to build the chairs. For most of them it was their first time doing anything like that. There’s something very satisfying about learning how to build something new with your own two hands. And as Matthew Crawford pointed out in his book Shop Class As Soulcraft, learning how to use tools is an important part of a liberal education.

Next I dashed off to buy pizza for a midterm exam. Yeah, you read that right. My ancient and medieval philosophy class put Socrates on trial earlier this semester and I promised them a meal together as a treat after the trial went so well. I redesigned the midterm exam to be a symposium, i.e. a dinner party. Here’s the idea: I gave them a question to consider (Why does Aristotle write about God in Book Lambda of his Metaphysics?) and allowed them to research it, to research related topics in the other philosophers we have read, and then to come to class with books, notes, and ideas. We sat down at a table together and served the pizza, then we opened the floor with that question. I kept a “conversation map,” and the students knew that the aim was not really to answer the question but to talk about what the question opened up. And another aim was to make sure everyone participated in the conversation. By the end of the hour, most of the pizza was gone (we got good pizza, and it wasn’t cheap when the professor pays out of pocket, but it was worth it) and everyone in the class–including the ones who are usually quiet–had talked about the topic in a way that helped others to think more clearly. After class one student came up to me and said she wished there were more classes like that where we can talk about big ideas (God, for instance!) without fear of offending or being canceled. I think the pizza helped, and so did the ground rules (try to include others, don’t pontificate or grandstand, questions are better than flat answers, open-ended questions are better than ones that invite a single word in reply, etc). But really, the students get credit for being amazing interlocutors, and for caring for one another.

My last class of the day is How To Live Well. We’ve been discussing Augustine’s Confessions, and I’ve also been peppering the class discussions with bits and pieces of other great philosophical texts from around the world. Again, the students were attentive, they asked good questions, and they seemed to care for one another. Not quite a lecture, and not quite a seminar, that class is a little Socratic and mostly me just trying to introduce them to big ideas that might help them examine their own lives and to care for others better.

I went back to my office after that and spent the next hour and a half talking to a stream of students who want to do practical things to make the world better. They have ideas, and they need a little guidance, maybe an advisor for a project or a mentor. Those conversations are soul-filling, especially knowing that what these students begin they are likely to carry onwards.

So here I am at home, typing up a record of the day. My back is tired from carrying lumber and my knees are a bit worn from kneeling on the pavement while we assembled the chairs. I often wish I had a budget to help pay for the tools or lumber, or to pay for pizza, or to fund the projects the students want to begin. For now I remind myself: we don’t have much, but we have enough. And that’s not a bad place to be. The students are alright, and it’s a joy to spend my day working and thinking and talking with them, and watching them blossom and flourish.

Taught twenty students how to make Adirondack chairs today. It was part of a class taught by our Registrar, and hopefully these chairs will provide a nice outdoor study spot!

Watercolor Gifts

At lunch today a friend gave me a watercolor set. He said when he saw it he knew he had to buy it for me and I am honored by this. So I came back to my office and painted another owl for him.

The point, of course, is not to paint perfect owls.

The point is to offer gratitude for friendship, and to give “productivity” its meager due while getting to know the birds a bit better.

Other tasks will get their moment soon but not yet. First, I have to clean my brush and pen.